Winnipeg General Strike 1919-2019

The second round of the 1919 strike

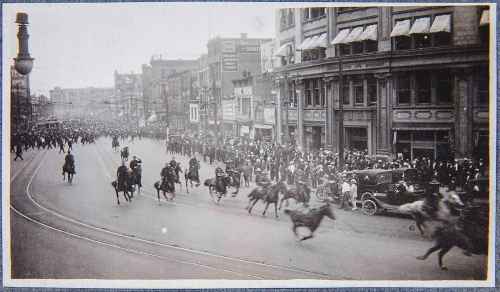

5 minute read Wednesday, Jul. 3, 2019The Winnipeg forecast had predicted cool weather for July 1, 1919. But it turned out to be sunny and warm on Dominion Day — the first one to be celebrated since the end of the Great War on Nov. 11, 1918, as well as the conclusion of the six-week Winnipeg General Strike only five days earlier, which had torn the city apart.

“Throngs of happy holiday-makers,” as the Free Press described them, streamed into Assiniboine Park all day. Thousands, too, hopped streetcars and headed to River Park, then a popular destination in the South Osborne area along present-day Churchill Drive. The 10th Garrison band offered a musical program at the park. Many Winnipeggers boarded CN trains for a ride to Grand Beach and Winnipeg Beach to frolic on the shores of Lake Winnipeg.

Everything was apparently back to normal in the city. “Peace for the world was declared and Winnipeg had its own special peace,” a Free Press editorial declared. “The tension of weeks, the disturbing, dissatisfying atmosphere that had enveloped the civil body politic had disappeared and the community set itself to enjoy to the full the finest anniversary of Confederation the community has known for years.”

It was true the general strike had been called off and officially ended June 26 without the Central Strike Committee and its supporters achieving their main goals of collective bargaining, union recognition and higher wages. But there was, in fact, no “special peace” to be had in Winnipeg.

Advertisement

Weather

Winnipeg MB

-9°C, Blowing snow

Don’t romanticize the Winnipeg General Strike

5 minute read Preview Thursday, Jun. 27, 2019A century after the General Strike, the wealth gap endures

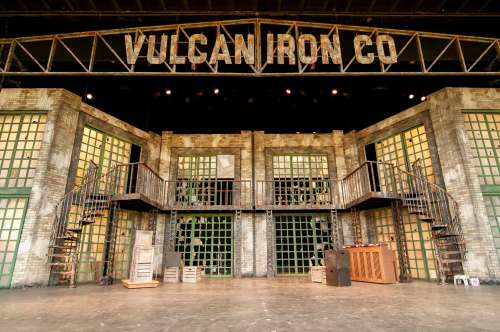

4 minute read Preview Wednesday, Jun. 26, 2019Local musical produced at the scale it deserves

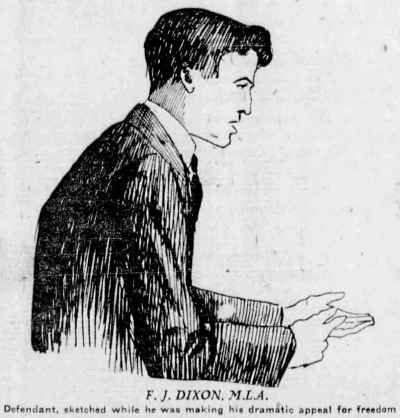

4 minute read Preview Friday, Jun. 21, 2019Press freedom a key issue in Winnipeg General Strike

5 minute read Preview Friday, Jun. 21, 2019Workers have won rights and protections since the 1919 General Strike; but unions hold far less sway in Canada

22 minute read Preview Friday, Jun. 21, 2019Strike casualties were immigrants searching for brighter future

4 minute read Preview Friday, Jun. 21, 2019Strike! The Musical features same story arc, new characters, songs

5 minute read Preview Saturday, Jun. 15, 2019In the water

6 minute read Preview Tuesday, Jun. 18, 2019The Social Page

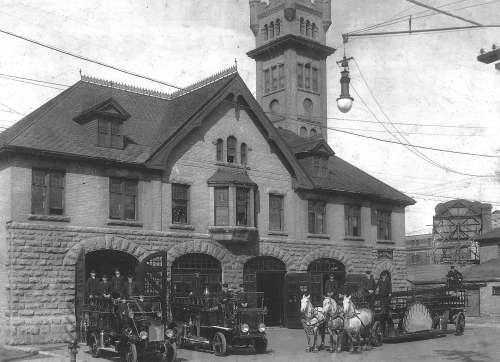

1 minute read Preview Tuesday, Jun. 18, 2019Firefighters faced dangerous working conditions but didn't get enough respect

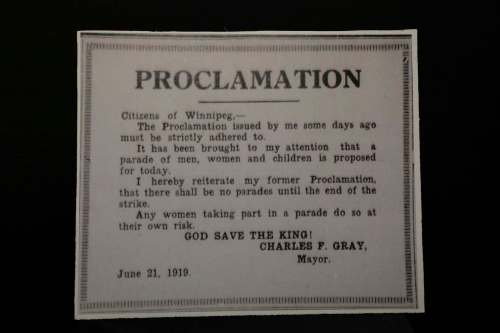

6 minute read Preview Tuesday, Jun. 11, 2019Former Winnipeg mayor played pivotal role in opposing labour movement

4 minute read Preview Saturday, Jun. 8, 2019Figuring out what to do with labour leaders was no easy task

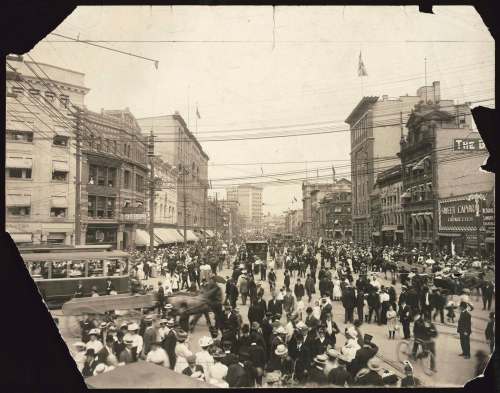

7 minute read Preview Saturday, Jun. 8, 2019Faces in the crowd

1 minute read Preview Saturday, Jun. 1, 2019Brookside Cemetery tours feature fascinating figures connected to General Strike

7 minute read Preview Saturday, Jun. 1, 2019Women's role in 1919 strike only now coming into focus, but full picture still missing

8 minute read Preview Saturday, May. 25, 2019LOAD MORE