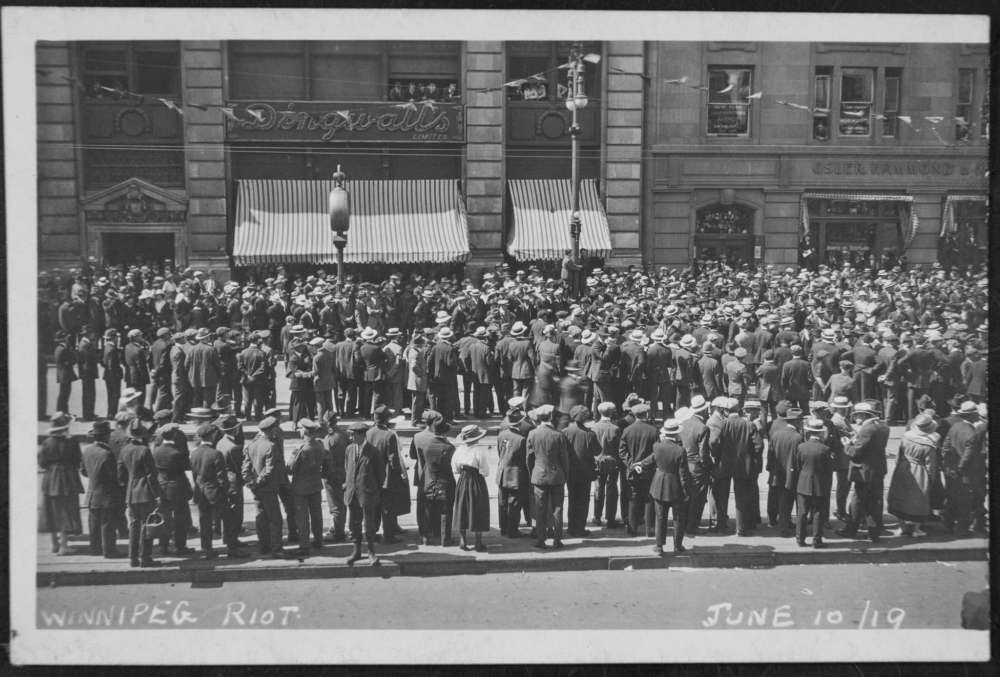

State of the unions Workers have won tremendous rights and protections in the 100 years since the Winnipeg General Strike; but unions hold far less sway in Canada

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 21/06/2019 (2456 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

She didn’t tip over a streetcar, but Basia Sokal’s bold departure from the Winnipeg Labour Council in March still made a thud — and lifted the veil on cracks in the local movement’s solidarity.

Sokal has since returned to her former job as a full-time letter carrier and union organizer with the Canadian Union of Postal Workers (CUPW).

The day after her very public exit and again in an interview about two months later, she described her resignation from the labour council as her own version of the 1919 Winnipeg General Strike.

“It breaks my heart that I feel the need to tell you this, but we need to do better,” she said during her last speech to the council March 19, which was uploaded online later, causing a maelstrom.

For about 15 minutes, she told a roomful of union leaders and delegates about alleged harassment she experienced from within their ranks during her 26-month stint as labour council president.

“‘You women are all the same. If you don’t like what’s going on, why don’t you just leave?’” Sokal said she was told by union brothers, as well as: “‘Let me tell you a story about what happened to the last person who didn’t agree with us,’” and “‘Nice tits.’”

Fallout from Sokal’s departure is still happening. Last month, the labour council passed a motion banning guests from attending meetings without permission from the executive. The Canadian Labour Congress (CLC) continues to investigate her allegations as well, according to president Hassan Yussuff.

Perhaps most importantly, Sokal’s actions spurred discussion about what the union movement should be prioritizing and whether it’s turned away from its grassroots beginnings.

One hundred years after the 1919 Winnipeg General Strike, what is the state of our unions? Well, that depends largely who you ask.

If it’s Sokal, the picture isn’t pretty. During a dozen other interviews conducted this spring, local and national labour activists had a wider range of responses.

Gord Delbridge, president of Canadian Union of Public Employees (CUPE) Local 500, said the labour movement is “becoming stronger because of and in spite of what this (provincial) government’s doing.”

Michelle Gawronsky, president of the Manitoba Government and General Employees’ Union (MGEU), described a prolonged strain put on health-care unions by Bill 29 (The Health Sector Bargaining Unit Review Act).

Since the introduction of that bill in March 2017, 10 unions were pitted against one another in a contest to win back their members. Premier Brian Pallister’s Progressive Conservative government wants to scale back the number of collective-bargaining agreements in health care, moving from 180-plus contracts province-wide, to a maximum of seven bargaining units per employer.

Union members are expected to vote on which union they’d like to see represent them between Aug. 8 and Aug. 22. The official four-week campaign period will start July 11.

“It causes tension, (but) I can still sit down and talk to any of the union presidents,” Gawronsky said of the contest.

“Again, I can only speak for MGEU. But when we’re out there campaigning we are not out there bashing any other union. We stand in solidarity in labour.”

As might be expected, Sokal had more dire predictions about the labour movement.

During event preparations for the 100th anniversary of the strike, she realized she wanted to walk away from the labour council.

“We were talking about all of the gains that workers made in the last 100 years and I just felt like things are actually really bad for women right now in the labour movement, and especially women of colour and queer women and Indigenous women,” Sokal said.

“I look around our rooms and our rooms are very pale, stale and male.”

“I look around our rooms and our rooms are very pale, stale and male.”–Basia Sokal

While she has felt shunned from labour circles since her resignation, Sokal said she is happy to be back at her old job delivering mail. Her mood is noticeably brighter.

“Sometimes I think the best way to fix things is to get it out, burn it down and start again,” she said.

“I don’t air dirty laundry,” she added. “I clean it up.”

•••

At a time when long-term employment stability in North America is increasingly precarious, unions represent only about 30 per cent of workers Canada-wide and 34 per cent of the workforce in Manitoba.

The peak of union membership occurred in the 1970s. Between 1981 and 2012, rates declined from 38 per cent to 30 per cent nationally, according to Statistics Canada.

!function(e,t,s,i){var n=”InfogramEmbeds”,o=e.getElementsByTagName(“script”)[0],d=/^http:/.test(e.location)?”http:”:”https:”;if(/^/{2}/.test(i)&&(i=d+i),window[n]&&window[n].initialized)window[n].process&&window[n].process();else if(!e.getElementById(s)){var r=e.createElement(“script”);r.async=1,r.id=s,r.src=i,o.parentNode.insertBefore(r,o)}}(document,0,”infogram-async”,”https://e.infogram.com/js/dist/embed-loader-min.js”);

In the meantime, the gig economy grew. About one-third of Canadians now have jobs that aren’t traditional nine-to-fives; they may, over time, hold many part-time and / or temporary contract gigs to make ends meet.

The number of part-time workers swelled from about 1.6 million in January 1981, to closer to 3.6 million in January this year (about a 125 per cent jump).

Advocating for those at-risk employees — most of whom don’t have unions to stand up for their rights — is among the most difficult things unions need to learn to do, said Fred Wilson, a retired director of strategic planning with Unifor, Canada’s largest private-sector union.

He recently wrote the book, A New Kind of Union, about how Unifor was created in 2013 from the merger of the Canadian Auto Workers union and Communications, Energy and Paperworkers of Canada.

Wilson acknowledges labour needs to widen its tent and merge its might even more. He points to growing wage gaps as a sign of the labour movement’s erosion.

“It’s not even that workers don’t want unions — they don’t even know what unions are.”–Fred Wilson

“Why is wealth inequality growing? Well, private-sector union density is declining. So more and more working people have fewer unions. And there’s whole sectors of the economy in which unions are hardly relevant,” he said.

“And it’s not even that workers don’t want unions — they don’t even know what unions are.”

Data from Statistics Canada shows about 75 per cent of public-sector employees were unionized in 2018, compared with just shy of 16 per cent of private-sector workers.

!function(e,t,s,i){var n=”InfogramEmbeds”,o=e.getElementsByTagName(“script”)[0],d=/^http:/.test(e.location)?”http:”:”https:”;if(/^/{2}/.test(i)&&(i=d+i),window[n]&&window[n].initialized)window[n].process&&window[n].process();else if(!e.getElementById(s)){var r=e.createElement(“script”);r.async=1,r.id=s,r.src=i,o.parentNode.insertBefore(r,o)}}(document,0,”infogram-async”,”https://e.infogram.com/js/dist/embed-loader-min.js”);

For unions to stay politically relevant, they need to recruit more and effectively spread their gospel, Wilson said.

With a federal election about four months away, he worries labour has no real strategy to block Andrew Scheer’s Conservative party from victory.

“The consequences of a majority Conservative government would be devastating for union people, and the writing’s on the wall,” Wilson said. “The way in which Scheer is playing the media (as the)-enemy-of-the-people card, trying to make a proxy fight against the unions.

“It’s setting up, of course, if they form the government, for another round of attacks (and) of assaults on trade-union rights.”

CLC president Hassan Yussuff said it’s “going to be a mixed bag in the next election.” Some unions affiliated with the congress will actively campaign for the NDP, while others focus more on where political parties stand on certain ballot-box issues, such as Pharmacare or green policies.

With Manitoba also on the brink of a provincial election — likely in September — the NDP might be stretched thin in terms of fundraising. Volunteer support could also be split between helping out with two elections in back-to-back months.

No matter who gets elected, unions need strong memberships in order to lobby governments for their political causes, Yussuff said. He points to gains labour has won in terms of expanding the Canada Pension Plan and securing domestic violence leave province by province. Manitoba enacted its own such policy in 2016.

Though many Canadians have anti-union attitudes, Yussuff said it’s up to the labour movement to educate the public about how it advocates for all workers, not just union members.

“And that story has to be told a million times, not just by me but by other affiliates at the provincial level,” he said.

“Because quite often, people don’t know what unions do, for the most part, and this is a daunting challenge…. Even 100 years ago, I don’t think people really knew what unions did. They just thought it was a vehicle for them to come together in solidarity to take on some big challenges.”

“Even 100 years ago, I don’t think people really knew what unions did. They just thought it was a vehicle for them to come together in solidarity to take on some big challenges.”–Hassan Yussuff

Fifty years ago – and 50 years to the day after Winnipeg’s general strike ended in 1919 — Manitoba elected its first NDP government. The labour-affiliated party has since represented the province more often than not, governing for 32 of the last 50 years.

Yussuff and other local union leaders said labour laws in Manitoba are fairly strong as a result of the prolonged NDP reign.

Now under Pallister’s government, the labour infrastructure looks like it’s starting to take a bruising, with collective-bargaining rights — a victory dating back to the general strike — among the first to take a punch.

•••

In March 2017, the Pallister government introduced Bill 28. The legislation was challenged immediately by nearly as many unions.

The Public Services Sustainability Act seeks to impose four years of wage controls on new collective agreements, freezing out salary or benefit increases for the first two years. Agreements would allow for a maximum pay increase of 0.75 per cent in the third year and a one per cent raise in the fourth. The act would affect at least 110,000 public-sector employees.

A coalition of 25 unions are fighting the bill’s constitutionality in court, with their next hearing scheduled for November.

Manitoba Federation of Labour president Kevin Rebeck said Bill 28 strips union members of their collective bargaining rights.

“We’ve got a premier here in Manitoba who we believe is violating our charter right to free and fair collective bargaining,” Rebeck said.

“Workers are being told, without being able to set foot at a bargaining table, that there’s a pre-determined outcome and you’re going to get zero and zero for the next two years. That’s not moving people forward and people aren’t keeping up with cost of living.”

Julie Guard, a professor of labour studies at the University of Manitoba, said Bills 28 and 29 are “clearly anti-union legislation” and the legislation could possibly be undone in court.

“It’s debatable. I’m not the Supreme Court, but it looks to me like this is an attack on their right of free association,” she said of Bill 29, which hasn’t faced a court challenge yet.

For Rebeck, there’s a sense of irony that Manitoba unions are again fighting for their rights to collective bargaining while celebrating the general strike’s 100th anniversary.

“For a long time since the strike of 1919, there’s been relative labour peace. You know, we’ve found better ways in the past to work together, to collaborate, to problem-solve. But it really feels like the Pallister government wants to turn back the clock in a big way,” he said.

“(The premier) is disregarding even when labour and business come together and say, ‘Hey, we agree on this. We’re the stakeholders. Please do something this way.’ They say, ‘Well that wasn’t our plan, so thanks for your advice,’ and they go another way.’”

Their disagreements with the Pallister government include squabbles on public mediation services (which the government is trying to eliminate), on the legal working age being set at 13 years old (which the federation says is too low) and on proposed amendments to the Workplace Health and Safety Act (outlined in one of five bills the opposition NDP has deferred until fall).

“Actually, I think the labour movement has been coming together stronger under this kind of environment,” Rebeck said.

“We’ve been growing our federation of labour. The (Manitoba Nurses Union) joining us (in May) was a great big boost and move. We’re united together on these legal challenges. We’ve been united together at more and more rallies and events that we have to stand up together for.”

Health-care consolidation has led to several mass protests across Winnipeg in the past two years. The more recent rallies at Concordia and Seven Oaks General hospitals have drawn hundreds; hospital employees pour outside during their breaks to decry the system changes, which several union members compared to accounts of the collective spirit shown by participants in the General Strike.

“As professionals, we typically don’t tend to sort of want to tip over buses and light fires and storm the government buildings and things,” said Bob Moroz, president of the Manitoba Association of Health Care Professionals.

“What I’ve been noticing lately is certainly there’s a lot more people becoming active.”

"As professionals, we typically don’t tend to sort of want to tip over buses and light fires and storm the government buildings and things,"-Bob Moroz

Whereas in years past, MAHCP sometimes struggled to get people out to events, now Moroz said he’s seeing union members snatch their flags directly out of his hands to show their support. They make no qualms about protesting directly in front of their employers.

MAHCP represents about 4,000 health-care workers, most of whom are also impacted by Bill 29’s representation votes. Moroz described the bill as a distraction meant to keep the health-care unions busy while the province makes major health-care changes.

“I think they’ve made a mistake,” Moroz said of the government’s plan.

“Yes, unions are forced to campaign for their own membership and different members. But on the other side, when it’s all over, there’s still a huge amount of solidarity that’s being built,” he noted.

“Despite what we see in the media with some of our colleagues and some of the things that are out there…”

•••

The main dustup recorded by media so far was between the two largest unions representing health-care workers: MGEU and CUPE.

In January, MGEU held a news conference where they talked about worries the province might try to use home-care workers and hospital health-care aides interchangeably, since the employees were being lumped together in the same bargaining unit for future collective agreements.

“Only a high-priced consultant who isn’t working on the front lines would try to improve quality of care by shuffling health workers around the system,” MGEU president Gawronsky said at the time.

The next day, CUPE came out with a rare public swipe at another union.

“We believe that’s a gross exaggeration of what that process would ever look like,” Liz Carlyle, a CUPE national representative, said Jan. 25.

“We believe that is really just fear-mongering on MGEU’s behalf because they don’t want to answer for what’s in their collective agreements.”

Since Bill 29 was introduced about two years ago, unions have been paying frequent visits to health-care facilities, hosting coffee breaks and placing their advertisements on bus benches, billboards and garbage cans all over town, all in an effort to woo members.

Both CUPE and MGEU said their advertising spending is approved by their respective boards and members, though they wouldn’t say how much the campaigns are costing. Gawronsky estimated “all the unions are into millions of dollars at this point” for the campaign.

She and other health-care union leaders discussed how, early on, they offered the premier an alternative to Bill 29. They were all willing to sit down at the same bargaining table and hash out identical collective agreements, if it meant keeping their respective members.

From Strike to Schreyer

When the third-place New Democrats were elected to government in 1969, “nobody was more surprised than everyone,” according to the front page of the Winnipeg Tribune.

For the first time in Manitoba’s history, the NDP were in charge — 50 years to the day after Winnipeg’s 1919 general strike was broken June 25.

When the third-place New Democrats were elected to government in 1969, “nobody was more surprised than everyone,” according to the front page of the Winnipeg Tribune.

For the first time in Manitoba’s history, the NDP were in charge — 50 years to the day after Winnipeg’s 1919 general strike was broken June 25.

The man of the hour was premier Edward Schreyer.

In an interview last month, nearing the 50th anniversary of his government’s swearing-in, Schreyer described a direct correlation between the seeds laid by the strike and the election of Manitoba’s first labour-affiliated government half a century later.

“That’s all remarkable coincidence,” Schreyer said of the timing of his first victory.

“But the substance is that the Winnipeg general strike of 1919 did lay the groundwork of sort of a more solid basis for the trade-union movement in Canada, and a growing awareness among working people about the importance of unity.”

Schreyer served as premier for 100 months, ushering in a slew of policy changes that still affect modern life in Manitoba, including the creation of Manitoba Public Insurance and amalgamation of the City of Winnipeg.

His decisions weren’t always popular. Case in point, siding with Liberal prime minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau on enacting the War Measures Act during the October Crisis of 1970.

Still, Schreyer remains one of the most popular Manitoba New Democrats. He will be fêted at an NDP fundraiser next week.

Ask about the Winnipeg General Strike and Schreyer becomes a talking encyclopedia, rattling off spools of history. He segues into how the strike spurred the creation of the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF), co-founded in 1932 by strike leader J.S. Woodsworth and the future father of medicare, Tommy Douglas.

In 1961, the Canadian Labour Congress and the CCF forged ties to develop the New Democratic Party — “a smooth, seamless transition,” as described by Schreyer.

He noted that, in 2019, the relationship between the labour movement and the NDP still requires some separation.

“You can’t have one run the affairs of the other, I’ll put it that way. What the labour movement can do is support and encourage policies by the political party that it supports,” Schreyer said.

“(Labour) can foster and promote and encourage those policies which it feels are most beneficial and sympathetic to working people. That’s what it’s all about.”

After the strike, many labour activists entered into politics and changed working conditions from the inside, out. Some even concurrently held seats in the Manitoba legislature and at Winnipeg’s city hall, such as mayor and MLA John Queen in the 1930s and 40s.

After the Great Depression and into the 1940s, labour laws, health and safety regulations began to beef up. Union activity continued to grow in Canada until the 1980s, when it began its steady decline.

That’s when the economy took a giant “U-turn,” according to Schreyer (who’s also a retired economist). He likened the move to an ocean liner doubling back on itself when supply-side (or trickle-down) economics took hold.

“The labour movement lost its momentum. The slow but steady improvement in wages came to an end and then you had basically wage-income stagnation and soaring income for executive echelons and for large shareholders,” Schreyer said.

“And as a result, all of the improvement in relative wages and income and wealth that were taking place in the late ’40s, ’50s, ’60s, ’70s came to a halt.”

Schreyer is disappointed by the income disparity he’s witnessed in the last 25 years, pointing out CEOs’ ballooning salaries while far more folks experience crippling debt.

Now 83 years old, he claims not to follow Manitoba politics closely.

“I don’t pretend to keep up with internal political manoeuvres on most other issues,” he said.

Schreyer notes he will tune in for any political developments on energy or environmental policies, anywhere in the world.

-Jessica Botelho-Urbanski

In an email, provincial spokesperson said that the “council of unions approach… would not have resulted in any reduction in the number of bargaining units in the health sector, or systemic improvements and efficiencies.”

“Bill 29 will lead to a more aligned health system, and improve the quality and consistency of patient care across Manitoba.”

Gawronsky said overall, the unions respect each other.

“We still have a good working relationship,” she said. “And again, we recognize who the culprit is that has instigated this.”

Meantime, Shannon McAteer, CUPE’s health-care co-ordinator, said the run-off votes should help employees determine which union is their best fit.

“We do a lot more grassroots (campaigning), a lot more going to meet face to face with the members. That’s where we focus,” McAteer said. “We don’t focus on expensive TV ads. We spend our money meeting with our members.”

“We tell them that no matter what, they’re going to have a collective agreement and they’re going to be protected,” she added.

“And if they choose CUPE, that they’ll be in the strongest collective agreement going forward. That’s what we believe.”

•••

United Food and Commercial Workers’ local chapter also has stakes in the health-care representation campaign, among a slew of other sectors.

UFCW Local 832 may represent the widest range of workers of any union in Winnipeg, many of whom are service-oriented. From school bus drivers to food plant workers, cannabis sellers, grocery store employees and more, UFCW also added some rarely unionized restaurant workers to its roster last winter.

Employees from two Stella’s locations voted to unionize in the wake of the damning Not My Stella’s social media campaign, the Instagram-led push that documented hundreds of allegations of workplace harassment and abuse from managers, two of whom were subsequently fired.

In December, Stella’s employee Tony Dempsey told the Free Press about how union drives might help rehabilitate the local restaurant chain in the face of public scrutiny.

“If we brought a union in, we could say to the public, ‘Look what we’ve done. You can come back now, we have protection,’” Dempsey said at the time.

The bargaining units from the Sherbrook and Osborne Street Stella’s locations have been working out the terms of their first contract agreements since March. A conciliator was brought in starting last month for a series of meetings with the employer and union.

UFCW Local 832 president Jeff Traeger said while he can’t speak publicly about the process yet, the union may have more to say soon.

He acknowledged service industry workers are among the most difficult groups to unionize, often due to high turnover at their jobs.

Having more women in leadership roles at UFCW may play a role in ensuring more equitable work environments, too, Traeger said. The union recently mandated gender parity on its national executive board, after delegates passed a resolution at their conference calling for equity among the highest ranks.

UFCW Local 832 secretary-treasurer Bea Bruske said legislating gender parity among leadership is a good move, at least for now.

“I don’t feel that there’s enough women in leadership yet that have organically been able to get there for a whole variety of reasons,” she said, listing family responsibilities and lack of child care among them.

“We’re very much a service-oriented union and so I do feel that women need to be at that table making the decisions, in terms of how money is allocated (and) what the projects are, because we are making up 50 per cent of the workforce that this union is representing.”

In 2019, women are more likely to be unionized in Canada than men. The trendline opposes what happened a century ago when it was mostly men who belonged to trade unions, during the mass workplace exodus of 1919.

As of May 2019, Canadian women were more likely to be unionized in the public sector than men, with about 1.89 million women represented, versus just over one million men.

Meantime, men are more often unionized in the private sector, with approximately 1.29 million men represented compared with roughly 688,000 women during the same month.

!function(e,t,s,i){var n=”InfogramEmbeds”,o=e.getElementsByTagName(“script”)[0],d=/^http:/.test(e.location)?”http:”:”https:”;if(/^/{2}/.test(i)&&(i=d+i),window[n]&&window[n].initialized)window[n].process&&window[n].process();else if(!e.getElementById(s)){var r=e.createElement(“script”);r.async=1,r.id=s,r.src=i,o.parentNode.insertBefore(r,o)}}(document,0,”infogram-async”,”https://e.infogram.com/js/dist/embed-loader-min.js”);

***

Despite women’s increased participation in the workforce and in unions, men still dominate labour’s leadership roles (as they do in most aspects of society). Yet all those the Free Press spoke to for this story acknowledged the diversity of their union boards should reflect the communities they represent.

Gina Smoke, Unifor’s Indigenous community liaison, said her biggest takeaway from the Winnipeg General Strike was the need to recognize women’s role in the labour movement.

After all, it was a handful of female telephone operators who first left work in 1919 before an estimated 30,000 others joined them.

“You don’t necessarily hear about it, but for years women have always been a backbone helping out in so many ways. So I think that as far as lessons go, I think we should get more recognition on things that women do within the labour movement,” Smoke said.

Guard, the labour studies professor from U of M, said unions appear to be trying to hire more diverse members into their offices.

The Manitoba Federation of Labour, for example, has brought in four new members to its executive council within the last few years. They represent young workers, Indigenous workers, workers of colour and in the LGBTTQ+ community.

“There’s also resistance, not just from the leadership, but also from the rank and file,” on inclusion efforts, Guard said.

“People want their unions to spend their money, spend their time protecting their interests, rather than diversifying or reaching out or doing new organizing. So there is that pressure because people do pay their union dues and they want something back for them.”

"If unions are going to survive in the 21st century, we have to kind of step off of our islands. Step off the island and reach out in a non-transactional way, a values-based way, to the new working class."-Fred Wilson

Rather than focusing on collecting dues, some labour activists spoke of welcoming more folks to the movement. Recruiting new members could make unions more affordable and accessible to all, they said.

“If unions are going to survive in the 21st century, we have to kind of step off of our islands. Step off the island and reach out in a non-transactional way, a values-based way, to the new working class,” said Wilson, the retired Unifor rep.

“Unions either do that and do that soon, or the continuing decline of private-sector union density will bring us closer and closer to the margins of political relevance. And we become more and more vulnerable to having our rights stripped.”

In that vein, Sokal called the labour council’s new visitor permission policy “disgusting.”

“That’s my problem with the labour movement. We’re preaching to our own choir, meanwhile there’s 70 per cent of non-unionized workers we should be talking to,” she said during a conversation at a Broadway café.

She pointed down the street to Union Centre and described the building as an “ivory tower.” Getting back to her mail-delivery route means she can reconnect with workers on the street, an avenue Sokal said she prefers.

“Those aren’t real struggles in that building. They’re, for the majority, paid really well in that building and we might not understand what it’s like to live on somebody’s four dollars a day, or on welfare, or on assistance, or on disability, or on CPP,” she said. “We talk about fighting for them, but are we actually?”

“It’s time for us to get out of our squares, out of our halls and our rooms and go where the people are.”

jessica.botelho@freepress.mb.ca Twitter: @_jessbu