A century after the General Strike, the wealth gap endures

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 26/06/2019 (2361 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

One hundred years ago this week, the Winnipeg General Strike, arguably the most influential labour action in Canadian history, staggered to its anticlimactic end.

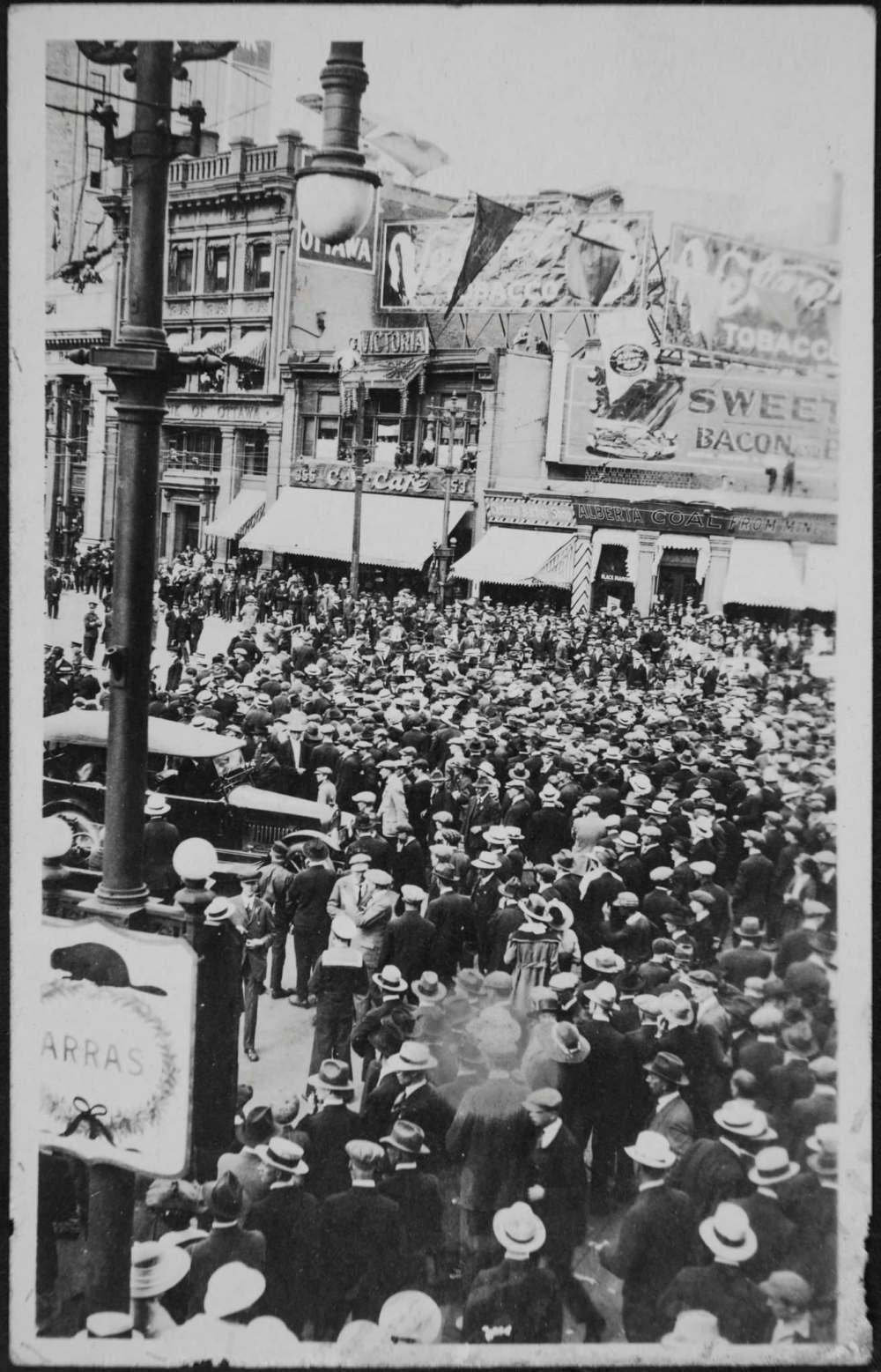

Hopes for a successful outcome had been crushed on June 21, 1919 — a day that became infamous as “Bloody Saturday” — when police armed with guns and clubs charged on foot and horseback into a crowd on Main Street.

One worker was shot and killed; another who was shot died later of gangrene. At least 30 others were wounded and a streetcar was famously tilted off its rails and set ablaze in the violent confrontation.

Five days later, at 11 a.m. on June 26, the six-week strike was officially ended.

What amounted to about half of Winnipeg’s workforce at the time returned, many of them bruised and bloodied, to their jobs, though some strikers found themselves unemployed as angry business owners meted out punishment where they could.

The workers failed to win concessions, although the historic walkout certainly changed the nation’s labour landscape and set the stage for workplace reforms that are commonplace today. One hundred years later, it’s impossible to say what the 1919 strike leaders would think of the state of labour relations in Canada today, but it seems likely a few recent headlines would have left them rolling in their graves.

For example, they would have been aghast last week to read the Canada Revenue Agency’s fifth and final report on the tax gap, the difference between the total amounts of taxes owed to the federal government versus the amount it actually received.

The CRA reported that Canadian companies avoided paying up to $11.4 billion in taxes in 2014, with small companies dodging between $2.7 billion and $3.5 billion in taxes, while bigger companies avoided paying between $6.7 billion and $7.9 billion.

While the agency expects to recoup up to 65 per cent of what it’s owed for 2014, it admits not all of the unpaid taxes involved companies knowingly trying to defraud the system. Often, it says, honest mistakes — ignorance of tax law changes or accidentally overclaiming deductions and credits — were to blame.

If they weren’t shocked by the size of the unpaid corporate tax bill, the leaders of Winnipeg’s 1919 strike would certainly have rolled their eyes at the compensation paid to modern Canadian executives. In its annual report earlier this year, the left-leaning Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives (CCPA) revealed Canada’s highest-paid CEOs earned an average of $10 million in 2017 — almost 200 times the average worker’s salary.

“Although this is slightly less than the year before, when they made $10.4 million, this year’s average is still the second-highest since we began keeping track (in 2008),” CCPA senior economist David Macdonald wrote.

A year earlier, when the average CEO wage was 209 times that of a typical worker, Macdonald sniped: “Canada’s corporate executives were among the loudest critics of a new $15 minimum wage in provinces like Ontario and Alberta; meanwhile, the highest paid among them were raking in record-breaking earnings.”

From the Occupy Wall Street protests of 2011 onward, there has been plenty of evidence of growing unrest over the widening gap between rich and poor. It’s unlikely — in the short term, at least — that such anger will manifest here in an uprising as incendiary as what happened in Winnipeg’s streets a century ago, but there are messages in the past month’s General Strike commemorations that the 21st century’s one per cent would do well to heed.