Complex case

Figuring out what to do with labour leaders was no easy task

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4 plus GST every four weeks. Offer only available to new and qualified returning subscribers. Cancel any time.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 08/06/2019 (2096 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

When the strike ended, the police and legal officials had eight men out on bail (George Armstrong, Roger Bray, Abe Heaps, Bill Ivens, Richard James Johns, John Queen, Bill Pritchard and Bob Russell) and four men in jail (Michael Charitonoff, Oscar Schoppelrie, Solomon Alamazoff and Mike Verenchuck), but were not sure what to do with them.

The men had been arrested under provisions of the Criminal Code of Canada, though the Attorney General had not given approval to make the arrests. After the arrests, the police did get the authority from the Minister of Immigration to apprehend the men, so the police could claim the men were suspected of Immigration Act violations. But the situation was complicated. George Armstrong was born in Canada and therefore was not subject to immigration laws. Moreover, if the other men were subject to the Immigration Act, the only punishment available would be immediate deportation. The authorities knew the men would become martyrs if they were deported, which very likely would provoke continued massive labour and public protest. Dropping charges and letting them go would imply the government made a mistake in the arrests. So, letting them go was not going to happen.

The legal option available was to put the men on trial as “leaders of the strike,” accused of sedition, of advocating the overthrow of the Canadian government. The problem with this option was that the provincial government was responsible for sedition-related offences and prosecutions, and the Attorney General did not believe there were grounds for prosecution. He said he would not take the men to court. Alfred J. Andrews and the Citizens’ Community of One Thousand were then in a position where their only option was to take on a “private prosecution,” which was allowed under the Criminal Code. If the justice system could not or would not prosecute, a citizen or group of individuals could allege a violation of the law and take an accused to a court for judgement.

As authors Reinhold Kramer and Tom Mitchell observe in their comprehensive analysis of the situation, “Perhaps the most compelling reason for Andrews’ use of the Criminal Code was his and the citizens’ growing wish to criminalize the strike. The leaders must be brought to heel, but the issue of general strikes in Winnipeg must also be settled definitively and publicly.” In a private letter to acting Minister of Justice Author Meighen dated July 10, 1919, Andrews put his strategy simply: “the only way to deal with Bolshevism is to hit and hit it hard, every time it lifts its ugly head,” which he did in the next six months of preliminary hearings and trials.

Russell was put on trial first in November 1919. He was considered a central figure in the strike. He was a member of the Winnipeg Trades and Labor Council, the Central Strike Committee, and the Socialist Party of Canada. He was the secretary of the Metal Trades Council and a promoter of the One Big Union. While ten men were labelled “strike leaders,” only Russell fit that title. He was an ardent union leader and open socialist, which were completely legal activities in Canada. But the prosecution set out to prove Russell had conspired to agitate dissent, to encourage others to destroy the legitimate government of the country and to install a soviet-style government. There were seven points to the indictment that claimed Russell and the others (the seven to be tried later) seditiously conspired to foster disaffection against the government, aided and abetted the publication of seditious literature and conspired to effect a seditious intention (an unlawful strike). Ultimately, these were steps in a revolution, which would obtain control of industry and property and introduce a soviet form of government, and this was done by being a “common nuisance” for the general public through the strike.

Andrews was the lead prosecutor in the Russell trial. He focused attention on what he claimed was a key issue in the charges against Russell and the others: “We say… their intention was to bring about discontent and dissatisfaction and what would be the logical result someday — revolution — someday attempted revolution — someday overturning the government,” author Jack Walker wrote. As Kramer and Mitchell explain, “Russell wasn’t on trial for what he said or intended, or even what other people did as a result of what he said, but rather, Andrews emphasized what ‘would… be the natural result of such words.’” In very simple terms, at the preliminary hearing in July for the men accused of sedition, Andrews said they “started the fire and it was still burning,” which he believed justified judicial punishment. The Russell defence team started by unequivocally stating there was no conspiracy among the men accused. Edward McMurray, defence counsel, argued there was no collusion among the men who had very different ideals, social backgrounds and political affiliations (for example, Dixon ran against Armstrong in the 1915 provincial election for different political parties). They put forward that Russell acted within his legal rights as a labour leader and a member of the SPC. They demonstrated how Russell made efforts to find a settlement to the strike and therefore was not seditious in his actions.

From the start, the defence challenged the rulings of the judge and the role of the prosecutor. The trial proceedings were dramatic and often confrontational. Judge Thomas Metcalfe frequently interrupted the defence counsel, limited their access to witnesses, pressed them continually for a speedier trail effort and continually sided with the prosecution. The counsel for the defence often strongly disagreed with Crown Counsel and Judge Metcalfe, challenging how he was conducting the proceeding. McMurray accused Judge Metcalfe of dishonouring him and stormed out of the courtroom in protest at one point. The other defence counsel, Robert Cassidy, was ejected from the court for challenging a ruling made by Metcalfe at another point.

The defence challenged the prosecution’s definition of Russell as a strike leader. In fact, James Winning acknowledged at trial and under oath that he was responsible for “leading the strike” through the CSC. Russell, Armstrong and Ivens were CSC members and were labelled “strike leaders.” None of the twelve other CSC members were labelled strike leaders or had criminal charges brought against them. Instead, the prosecution selected men for trial who had a public profile, who were articulate speakers and advocates, who held strong pro-labour views or were active socialists.

After the prosecution presented 703 pieces of evidence (largely publicly available books, magazines and documents) and a dozen witnesses over seven weeks of trial, Russell was found guilty on Dec. 24, 1919 (the judge allowed Russell to go home unescorted for Christmas Day). He was sentenced to two years in prison (but only served eleven months). Ivens summarized public opinion when he was quoted in the press and then repeated at his contempt-of-court hearing in February 1920, “The vitriolic attack of the daily press had deliberately poisoned the mind of the public. Bob Russell was tried by a poisoned jury, by a poisoned judge, and he is in jail tonight because of a poisoned sentence.”

Russell’s case was then sent to the Court of Appeals and to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in England. The appeals were rejected on the grounds there were no errors in court procedure.

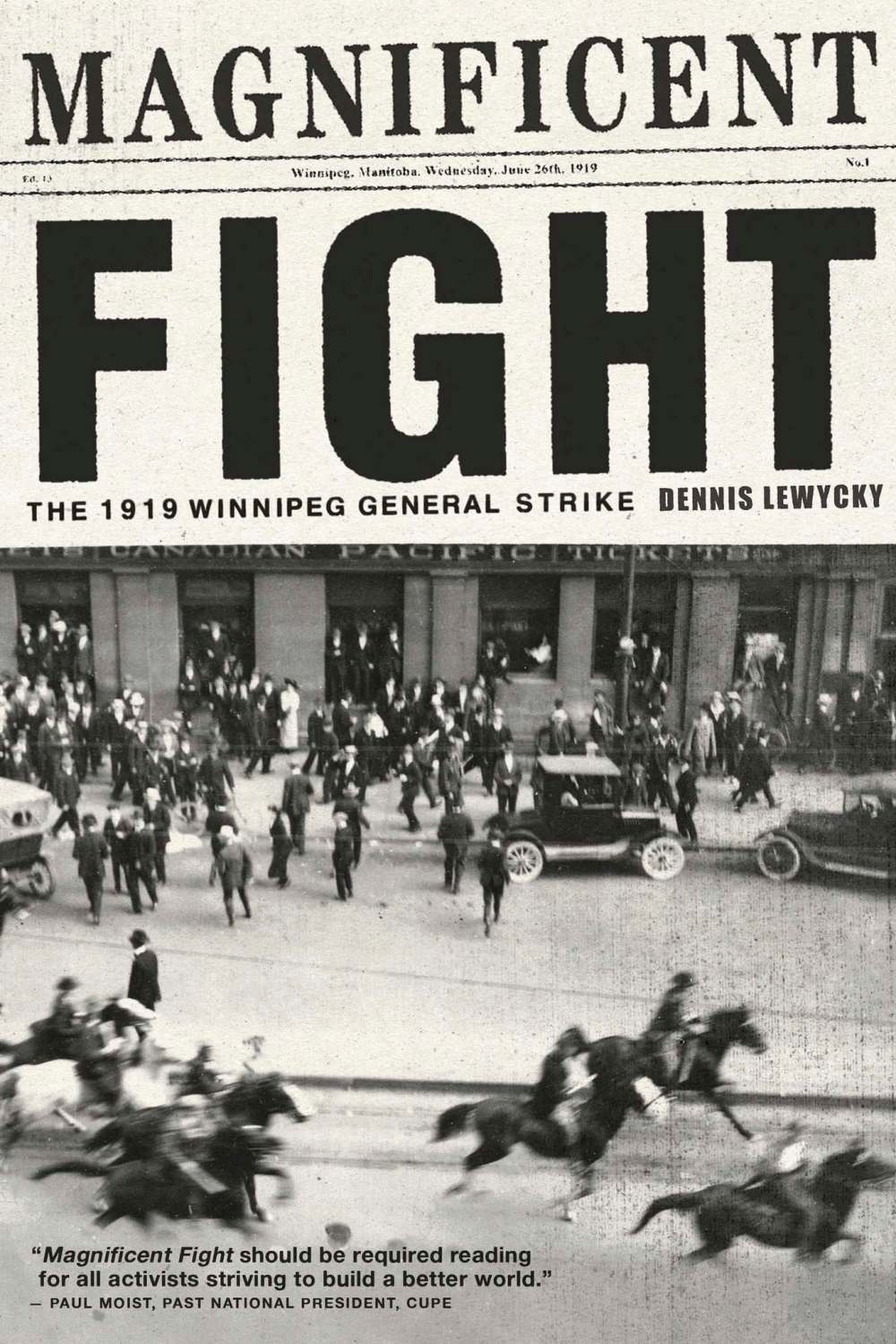

(Excerpt from Dennis Lewycky’s Magnificent Fight: The 1919 Winnipeg General Fight, Ferwood Publishing, 2019)