Taken for granted

Firefighters faced dangerous working conditions but didn't get enough respect

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4 plus GST every four weeks. Offer only available to new and qualified returning subscribers. Cancel any time.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 08/06/2019 (2096 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

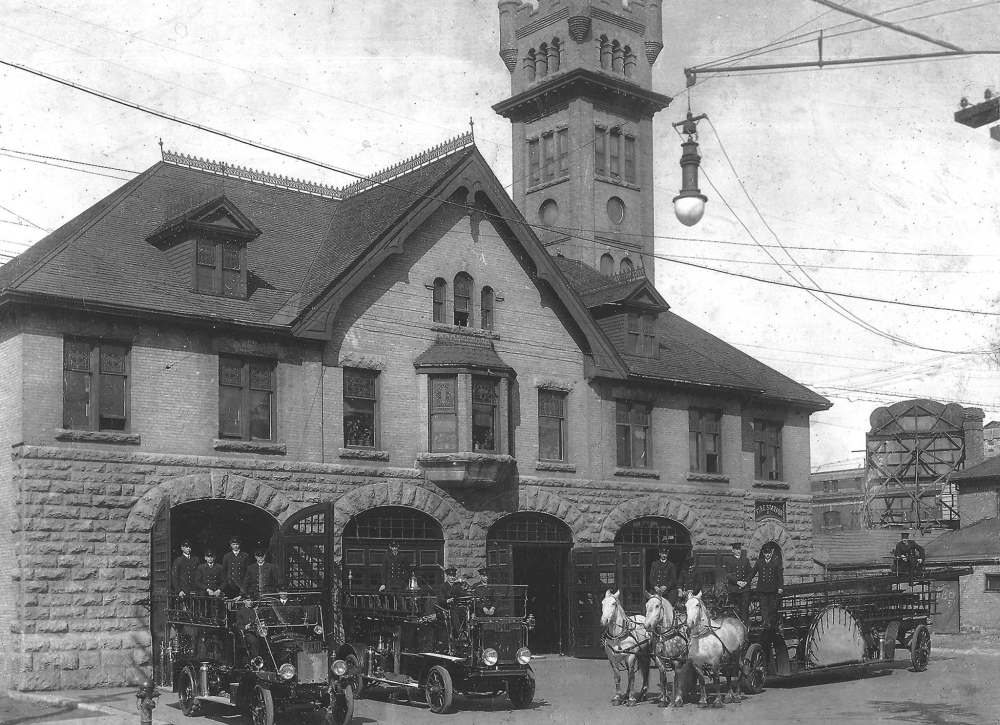

A new exhibit now being planned at the Fire Fighters Historical Museum of Winnipeg will tell the story of firefighters and the Winnipeg General Strike. The museum, a designated heritage site that served as an active fire hall from 1904-1990, is the first stop on the 1919 Winnipeg General Strike Driving and Walking Tour: 100th Anniversary Edition.

The Fire Fighters Museum is located at 56 Maple St. near Higgins Avenue and the former Canadian Pacific Railway station, which today is the Aboriginal Centre of Winnipeg. This train station was a major point of arrival for tens of thousands of newcomers in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Because of this, the fire hall was planned as a showpiece for the burgeoning city of Winnipeg. The building features ornate stained glass windows and pressed tin ceiling tiles decorated with firemen’s speaking trumpets. It is one of the oldest and most beautiful fire stations remaining in Canada, and its collections, which date to the days of horse-drawn carriages, steam-powered fire apparatus and bronze fire nozzles, are second to none.

Winnipeg firefighters were no strangers to labour activism in 1919. Their working life fostered a culture of caring, and they had been protecting one another on the job since the city’s first volunteer fire brigade formed in 1874. It was a time before universal health care, employment insurance and pensions provided any kind of social safety net. And so, like other workers, firefighters contributed to their own mutual benefit plan — the Winnipeg Firemen’s Benevolent Association. This society provided financial assistance to its members in times of sickness, injury and death.

Firefighting was difficult and dangerous work. Firemen, as they were called at the time, were required to live, make their meals and sleep at the fire hall. They worked 21 hours a day, seven days a week. They were admired for their bravery, skill and dedication, but they received little pay and could be fired for any reason. The rapid growth of Winnipeg’s population — from more than 40,000 residents in 1900 to almost 180,000 by 1920 — and the expansion of the city’s industrial and retail properties during these years made the demands of the job even harder.

Economic depression in 1912, followed by the start of the Great War two years later, made the times even more difficult. Families were facing not only staggering personal losses and injuries to enlisted men overseas, but also worsening conditions at home. The soaring cost of living, stagnating wages, high levels of unemployment and scarcity of goods that accompanied the First World War made life difficult for most Winnipeg workers.

Firefighters who were recruited to replace those who enlisted for military service when the First World War began also feared the loss of their jobs when the soldiers returned from overseas. In 1916, these concerns led to the formation of the Winnipeg Firemen’s Union.

When civic workers struck in 1918, with the support of the Winnipeg Trades and Labor Council and its commitment to take sympathy strike action, the firefighters joined in. All civic workers received a settlement that year. Winnipeg city council signed an agreement with the Winnipeg Firemen’s Federal Union Local #14. The new contract included modest wage hikes and a return-to-work protocol for all striking firefighters. But the right to strike for firefighters and the inclusion of officers in the union remained matters of dispute. Going on strike could mean dismissal.

The influenza epidemic that struck Winnipeg in the fall of 1918 and postwar inflation only added to workers’ problems. By 1919, most people — including firefighters — were fed up. Winnipeg and St. Boniface firefighters voted overwhelmingly to join other city workers, retail clerks, metal trades workers, needle trades workers, telephone operators, postal workers, machinists, bakers, confectioners, sleeping car porters, brewery workers, blacksmiths and more in the greatest labour stoppage Canada had ever seen.

Like members of the Winnipeg Police Department, firefighters were torn between their duties at work and their responsibility to their families and other workers. Although they voted to support the strike, they also pledged to provide full fire service where human life was in danger. Civic authorities rejected this offer. On May 26, city council dismissed the firefighters and all other civic employees who refused to return to work. The councillors passed resolutions prohibiting firefighters from joining international unions and from participating in sympathy strikes, and changed the firefighters’ contracts without consultation to reflect these changes.

The Citizens’ Committee of 1,000, which represented business leaders who opposed the strike, advertised for replacements and created a new fire brigade of 350 anti-strike volunteers. Reporting on events in Winnipeg on July 19, 1919, New York’s popular investigative journalism magazine Collier’s Weekly described “Winnipeg’s millionaire volunteer fire department” and said the new recruits represented “the gilded youth of the town.” Many were reported to be members of the elite Winnipeg Canoe Club. Another 300 volunteers were lined up by the citizens committee to guard the city’s fire alarm boxes and prevent protesters from setting off false alarms. The well-to-do volunteers were joined by returning soldiers, who either were opposed to the strike or were financially destitute and unable to find other work.

Archival photos show these men, smiling and sometimes brandishing billy clubs, while standing outside the fire halls or seated on the fire trucks during the strike. It was these strike breakers who hosed down the peaceful protesters assembled at Portage and Main, and took a pumper truck to the scene of the streetcar fire outside city hall on Bloody Saturday.

The end of the strike brought heavy penalties for those who supported the strike. Fifty-four of the 204 firefighters who joined the strike were fired. Some, who were near retirement when the strike began, lost their pensions. Those who were hired back were denied the holidays they were owed that year.

Despite these losses, and the adoption of the 1919 Fowler Agreement restricting the right to strike, those who remained on the job won better working hours and a small wage increase. The United Fire Fighters of Winnipeg joined the International Association of Fire Fighters as IAFF Local 867 and continued to fight for fair wages, safer working conditions and compensation for injuries and illnesses sustained on the job.

In 2002, Winnipeg firefighters made history when Local 867 became the first firefighters union worldwide to win presumptive workers compensation in recognition of the inherent dangers faced on the job.

Sharon Reilly is a former curator at the Manitoba Museum and the Canadian Museum for Human Rights. She and her husband Nolan are co-authors of the 100th anniversary edition of the Winnipeg General Strike Driving & Walking Tour.

The Fire Fighters Museum is open Sundays from 11 a.m. to 2 p.m. and by appointment. For further information, see firemuseum@gatewest.net, winnipegfiremuseum.ca or Winnipeg Firefighters Historical Society Museum on Facebook.

History

Updated on Tuesday, June 11, 2019 1:19 PM CDT: Opening times clarified.