Strike casualties were immigrants searching for brighter future

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4 plus GST every four weeks. Offer only available to new and qualified returning subscribers. Cancel any time.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 21/06/2019 (2083 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

In 2016, Ukrainians Canadians celebrated the 125th anniversary of the first arrival of Ukrainians to Canada and, in particular, to Manitoba.

No one leaves their country unless inspired by some selfless ideal, or compelled by reasons of an imperative nature such as politics or the economy. Manitoba played a significant role in the settlement of Ukrainians in Canada. From 1891 to 1914, our province was the first stopping place for many of these dispersed immigrants, the majority coming from western Ukraine. They were daring, dedicated, self-disciplined and filled with optimism.

The Great War of 1914-18 created difficulty for new Canadians to become natural citizens. Many Ukrainians came to Canada from a region that was under the Austro-Hungarian Empire at the start of the First World War. The Canadian government, under Sir Robert Borden, between 1914 and 1920, introduced internment camps throughout Canada, fearing that Ukrainians and other eastern European immigrants would have some form of affiliation with the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

This was an odd period in Canadian history — on one hand, many Ukrainian Canadians volunteered for service with the Canadian Expeditionary Force during the First World War, and at the opposite end of the spectrum, thousands of innocent Ukrainians and other Europeans became civilian internees, having found themselves declared enemy aliens simply because of where they had come from.

The attitude of the Canadian government toward immigrants from enemy countries during and after the First World War was on full display during the Winnipeg General Strike of 1919, because many strike workers in Winnipeg were immigrants who were presumed by some to be occupying jobs that should have been filled by returning soldiers.

The anti-strike Citizens Committee wanted the public to believe that returned soldiers were against the “enemy” aliens whom they believed were directing the Winnipeg General Strike. The committee created, in essence, an anti-immigrant propaganda scheme.

On May 15, 1919, the Winnipeg General Strike began, and thousands of unorganized workers joined those who were unionized in demanding that the provincial government guarantee the right of collective bargaining. By June 1, thousands of First World War veterans marched on the Manitoba legislature in support of the strike.

On June 21, there was a massive demonstration organized by the veterans, with a large involvement of immigrants in the strike. The North-West Mounted Police charged into the crowd on Main Street, swinging batons and firing at the protesters. With all the firing, only one man was killed, and another who was shot in the leg died later of gangrene infection as a result of his wounds. Both men were Ukrainian immigrants who shared a desire to become Canadian citizens.

Mike Sokolowski (a.k.a. Sokolowiski) was killed instantly by a shot through the head in front of city hall. He was buried at Winnipeg’s Brookside Cemetery (section 45, plot 450); his grave was unmarked for more than 80 years until June 20, 2003. As part of the Brookside Cemetery’s 125th anniversary, a donation was made to purchase a headstone for Sokolowski, who was from the Point Douglas area.

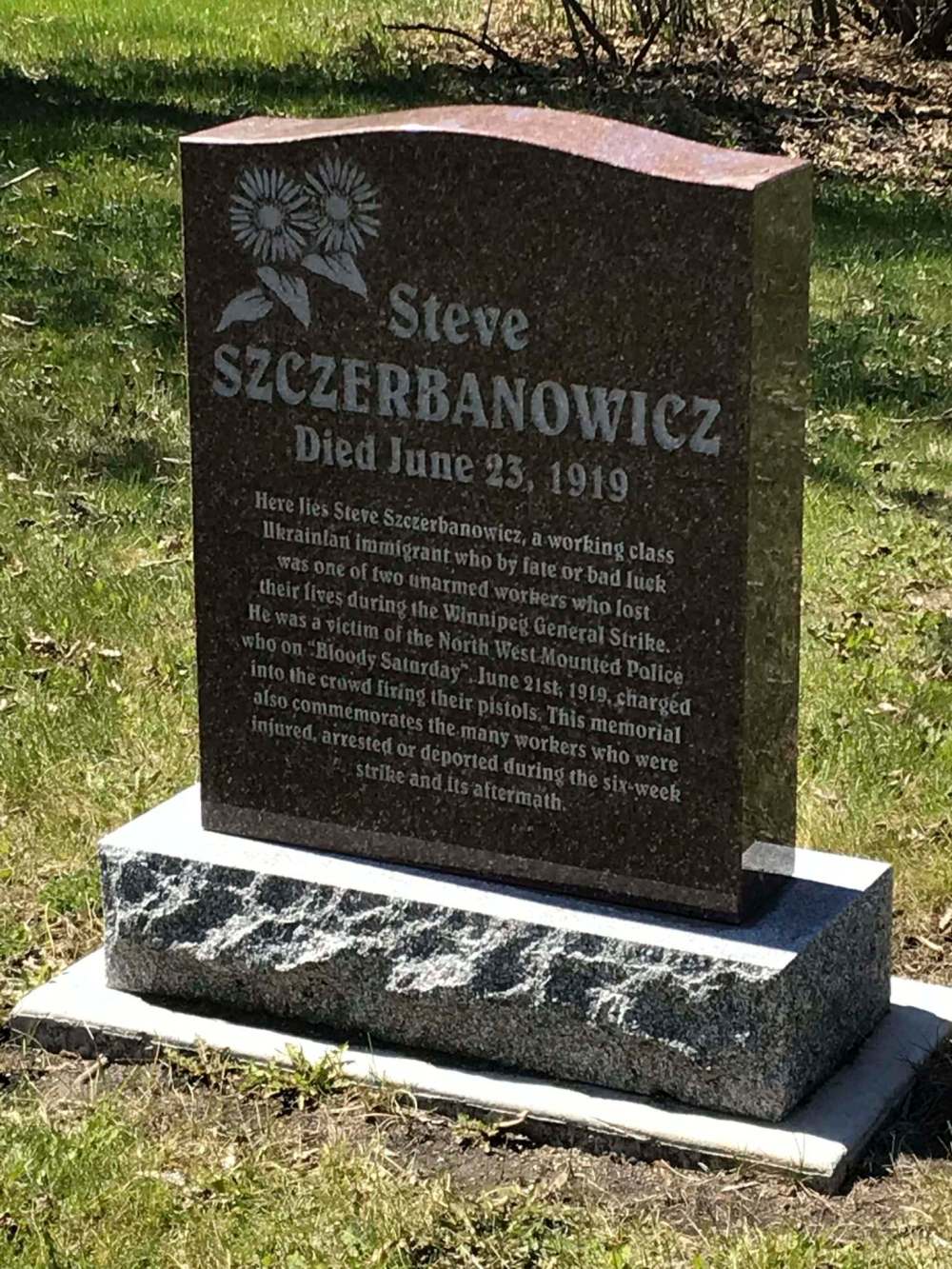

The other person, Steve Szczerbanowicz (a.k.a. Sheebaubucz, Schezerbanowicz, Schezerbanowes), was shot through both legs by a police officer. After he died because of a gangrene infection, nobody claimed his body. For 96 years, Szczerbanowicz was buried in an unmarked grave at Brookside Cemetery; on June 20, 2015, funds were raised to cover the cost of a gravestone in his memory (section 80, plot 7). No one will ever know whether Szczerbanowicz was a strike sympathizer, or just an individual curious as to what was going on during the riot.

To this day, the Ukrainian community doesn’t exactly know why Sokolowski and Szczerbanowicz were buried in unmarked graves for so many decades. They played a significant role in the events of June 1919; whether both were actively involved in the strike remains uncertain, but we can presume each was searching for a better life, seeking optimism in a new country.

Peter J. Manastyrsky is a member of the Ukrainian community of Winnipeg who writes articles on political issues.

History

Updated on Friday, June 21, 2019 9:26 AM CDT: Removes reference to Sir Wilfred Laurier