The second round of the 1919 strike

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4 plus GST every four weeks. Offer only available to new and qualified returning subscribers. Cancel any time.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 03/07/2019 (2071 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

The Winnipeg forecast had predicted cool weather for July 1, 1919. But it turned out to be sunny and warm on Dominion Day — the first one to be celebrated since the end of the Great War on Nov. 11, 1918, as well as the conclusion of the six-week Winnipeg General Strike only five days earlier, which had torn the city apart.

“Throngs of happy holiday-makers,” as the Free Press described them, streamed into Assiniboine Park all day. Thousands, too, hopped streetcars and headed to River Park, then a popular destination in the South Osborne area along present-day Churchill Drive. The 10th Garrison band offered a musical program at the park. Many Winnipeggers boarded CN trains for a ride to Grand Beach and Winnipeg Beach to frolic on the shores of Lake Winnipeg.

Everything was apparently back to normal in the city. “Peace for the world was declared and Winnipeg had its own special peace,” a Free Press editorial declared. “The tension of weeks, the disturbing, dissatisfying atmosphere that had enveloped the civil body politic had disappeared and the community set itself to enjoy to the full the finest anniversary of Confederation the community has known for years.”

It was true the general strike had been called off and officially ended June 26 without the Central Strike Committee and its supporters achieving their main goals of collective bargaining, union recognition and higher wages. But there was, in fact, no “special peace” to be had in Winnipeg.

On the morning of July 1, in an action the North-West Mounted Police later claimed had nothing to do with the strike, Mounties descended, SWAT-style, on the Labor Temple on James Avenue, as well as on 30 homes of known members of the Ukrainian Social Democratic Party, a Marxist party that had been banned by the federal government in September 1918. Similar raids had been carried out in Vancouver, Regina and Brandon.

In Winnipeg, literature seized at the Labor Temple and private residences was later revealed to have come “direct from Russia.” The Red Scare and the fear of a Soviet-style revolution that had gripped the city for months — and which had triggered the repressive actions of the Citizen’s Committee of 1000 and the federal government in arresting the strike leaders and dispatching the Mounties on horseback into the crowd that had gathered on Main Street on “Bloody Saturday”— had not suddenly vanished. “We are dealing with an attempt at revolution, and the public and especially the working classes should be made aware of it,” one officer involved in the raids remarked.

Four months later, that fear erupted again, more hysterically, in the civic election held on Nov. 28, 1919. The contest pitted strike leaders and labourites — labelled “radical socialists’’ — against former Citizens’ Committee members who were now organized into the “Citizens’ League of Winnipeg,” the predecessor of several business political organizations including the Independent Citizens’ Election Committee that dominated Winnipeg city council during the 1970s.

In 1919, mayor Charles Gray, who had opposed the strike, was being challenged by S.J. Farmer, a well-known labour figure. Other labourites were attempting to unseat pro-business aldermen (city councillors) in the seven seats being contested.

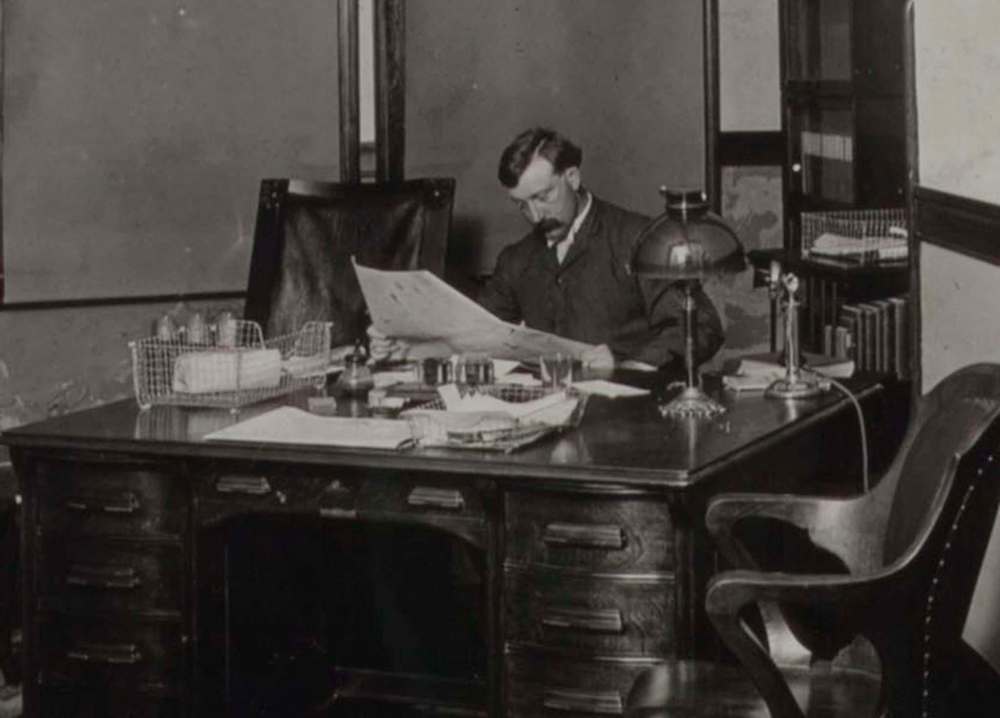

Yet, this was no ordinary election. Free Press editor John W. Dafoe, who had denounced the strike as “the Great Dream of the Winnipeg Soviet,” freely offered the pages of the newspaper to promote Citizens’ League propaganda. “The Citizens of Winnipeg have no fight against Labor,” one banner headline in the paper declared, “but they certainly have against the Reds in its ranks.”

Two days before the vote, Dafoe ran an editorial entitled “The Second Round of the Strike,” in which he tried to dispel the idea a majority of Winnipeggers had sympathized with the general strike. He warned civic voters to beware of the real intentions of Farmer and the other labour candidates should they be victorious. “Once safely in office with Winnipeg prostrate at their feet,” the editorial ominously predicted, “they will put into operation without compunction the programme of vengeance and spoliation to which they are committed.”

It was genuinely believed private property and services were at risk.

The election results on Nov. 28 were unsatisfying for both sides, indicating how divided Winnipeg remained. Gray easily held on to his position as mayor with 56 per cent of the vote — Farmer would be elected mayor in 1922 and serve for a year’s term — and city council was split between the Citizens’ League and the so-called “radical socialists,” who won three of seven ward seats.

The Free Press and Dafoe were not thrilled with the outcome of the civic election, but the next day’s editorial attempted to spin the positive aspect of the vote. Gray had been vindicated and several Citizens’ League candidates had retained their seats on council.

This fight between the two opposing sides was merely the beginning of an ideological battle that was to endure for decades. In the immediate aftermath, the results of the 1919 civic election “pushed” the Citizens’ League aldermen, as Stefan Epp-Koops shows in his 2015 book We’re Going to Run This City, about Winnipeg after the strike, “to change the election boundaries, reshaping the city’s political geography and curtailing labour’s chance for political success.” That strategy — like the current partisan Republican “gerrymandering” or manipulation of state boundaries in the U.S. — had only limited success.

Now & Then is a column in which historian Allan Levine puts the events of today in a historical context.