A sense of hope in Indigenous community Probe survey reveals optimism, confidence rising among younger First Nations, Inuit, Métis people

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 29/09/2021 (1619 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

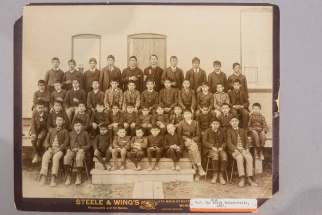

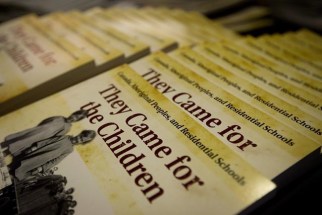

The hope Indigenous teen Miyawata Stout has for her future is one that is now three generations strong and forges links with her grandmother, a residential school survivor.

Miyawata, 15, is a student at Kelvin High School and, while she has a couple of years to go before graduation, she wants to become a physician.

But she admits the discoveries of unmarked graves at the sites of former residential schools across Canada in the spring and summer took its toll.

Kamloops, 215. Brandon, 104. Marieval, 751. The number of graves and locations grew with each passing week.

“That shook me up” she says. “It was hard to find hope there. It was really disheartening.”

Then she thinks of her grandmother, Madeleine Dion Stout, who not only survived the devastation of residential schools, but is her inspiration to become a doctor.

“I have hope because my grandmother has hope,” Miyawata says. “She had hope — that’s how she survived the residential schools. It is hope and it is strength which creates resiliency.”

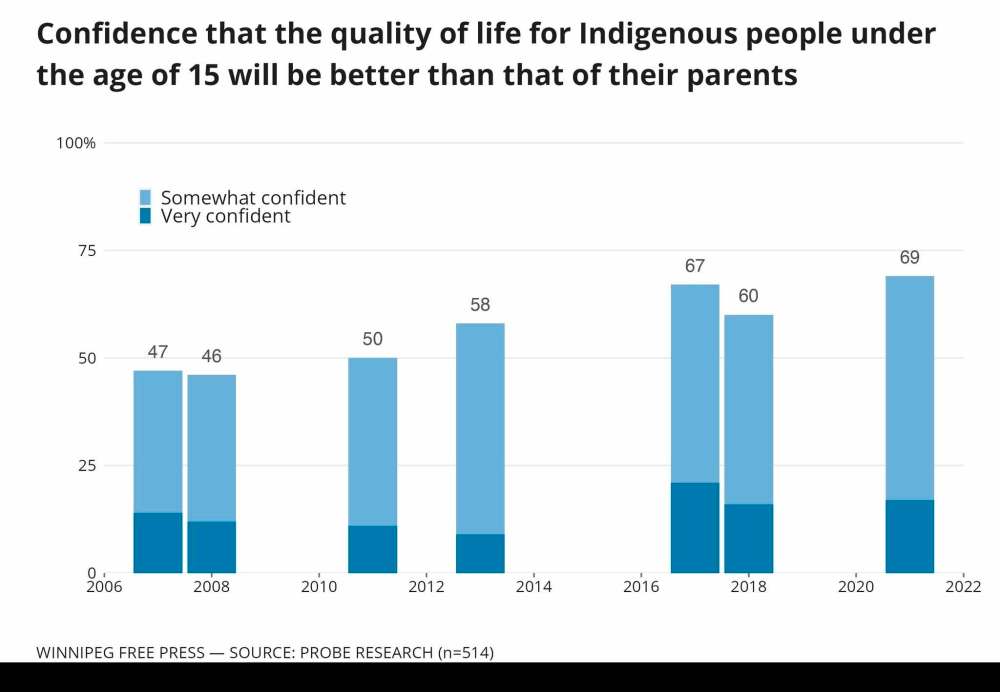

According to a survey of Indigenous people conducted by Probe Research — the eighth such omnibus survey undertaken since 2004 — hope for the next generation of Indigenous people is at its highest level since the research began.

More than two-thirds of Indigenous people are confident the next generation will enjoy a better quality of life than their parents, with 17 per cent being very confident and 52 per cent somewhat confident. Ten per cent said they were not at all confident. And those aged 18-34, the youngest category of people surveyed, have the greatest confidence, at 81 per cent.

That’s different than it was in the first two surveys taken by Probe. In 2007, only 47 per cent of Indigenous people said they were confident their children would have a better future. The percentage dropped slightly to 46 per cent in 2008.

A decade ago, Michael Redhead Champagne was involved in creating Meet Me at the Bell Tower, weekly gatherings on Selkirk Avenue with a mission to reduce violence in the North End.

“At 34, I’m now at the top end of being a youth, but I’ve been working with people much younger than myself for my entire adult career,” he says.

“Back around 2010, a lot of young people like myself were tired of waiting for organizations to help us. We wanted to help ourselves.”

Indigenous youth leaders in that part of the city are now able to regain their culture and take it home to their families.

“It is beautiful for their parents,” Champagne says. “And, what I see, and what I am able to witness, is the children having a better quality of life. The parents say they know what happened to them and they want better for their children.”

Adrienne Huard, a 34-year-old PhD candidate in Indigenous studies at the University of Manitoba, is a member of Couchiching First Nation near Fort Francis, Ont.

“In this faculty, I see a lot of hope. I see the generations coming up and I see how much fire they have,” Huard says. “They are grounded with who they are. I don’t even think my generation has it like they do.”

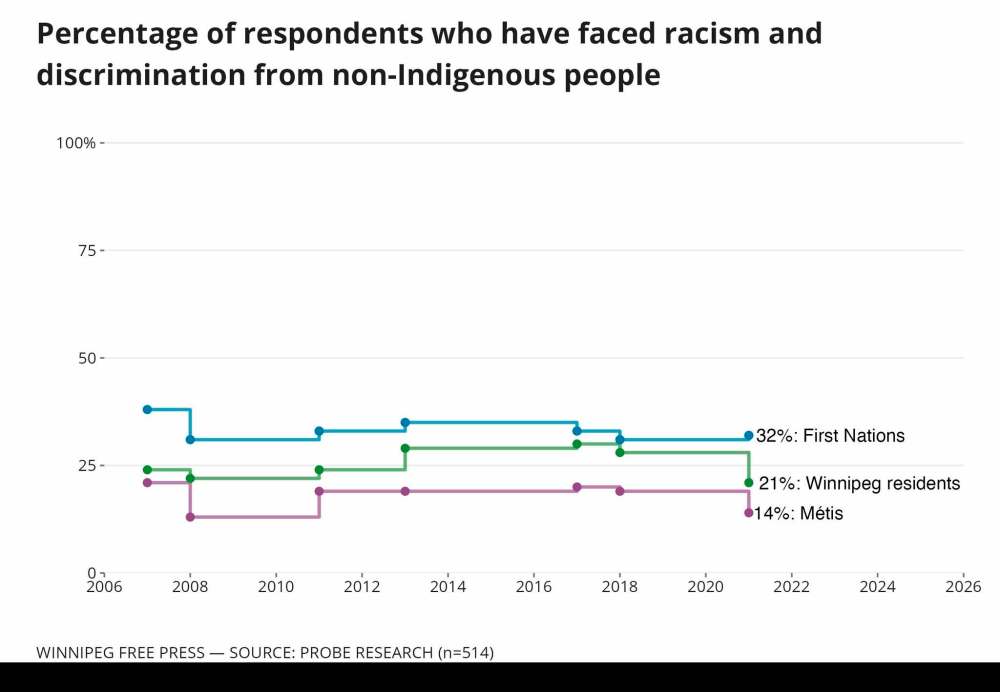

Racism, however, remains a constant presence in the lives of survey participants.

But while Métis and Indigenous people in Winnipeg report a decline in the volume of racism they face — survey results show the lowest numbers since tracking began — one-third of First Nations people and one-third of Indigenous men still report today they experience frequent racism.

Shauna Mulligan, who is Métis, still remembers experiencing racism as a young child.

“It was as young as elementary school,” she says. “I was in Grade 4 or 5 and we were talking about the history of Canada and they lectured about the North-West Rebellion (the 1885 insurgency against the Canadian government led by Métis leader Louis Riel), which we now call the Resistance.

“They said all Métis were traitors of the Crown and they were all bad people.”

Fast-forward to when Mulligan was a reservist with the Canadian Forces. She said a Métis colleague was sexually assaulted by another reservist.

“He said, ‘Well, she’s just a half-breed and no one will believe her,” says Mulligan, now 42, a PhD candidate and full-time lecturer at the University of Manitoba.

She says it made her think back to the advice she got as a child; her family celebrated their culture at home and with relatives, but not outside their front door.

“I was told when asked if you are Métis, tell them ‘no, I’m French,’” she says. “It’s so different now. I’m taking Michif, and I tell my students that, like any language, if you don’t use it you will lose it over time.”

“I was told when asked if you are Métis, tell them ‘no, I’m French. It’s so different now.” – Shauna Mulligan

And says she still hears what she knows is racism at the U of M, even if the person speaking doesn’t realize it.

“A professor will say, from a colonial perspective, that Indigenous people were ‘backwards.’ Excuse me, we were not. This perception we hold of Indigenous people unable to care for themselves is literally because of colonialism. I understand why they are saying these things, but they aren’t right.”

The Probe survey also found half of Indigenous respondents believe statues depicting colonial figures connected to the residential school system should be removed. Support to do that from First Nations people was at 56 per cent.

Miyawata says she was on the Legislative Building grounds on Canada Day when the statue of Queen Victoria was pulled off its pedestal. A statue of Queen Elizabeth II was toppled, as well.

“What I felt immediately was hope and only hope,” she says. “You could hear people talking about how to do it and then everyone pulled it down together.

“I don’t think most people even knew the statue was there. I don’t think it needs to go back there. It is up to our community to decide what goes there.”

Huard opposes the return of the statues.

“I think symbolically they represent something powerful in our community,” Huard says. “I don’t see any reason why they should be up.”

Laura Forsythe, who is Metis, is a PhD candidate and lecturer at the University of Winnipeg in the Faculty of Education. She points to the name on a new library in south Winnipeg as a missed opportunity for the city to have done the right thing.

The Bill and Helen Norrie Library is located on Poseidon Bay adjacent to the Pan Am Pool. It’s also located where a Métis community called Rooster Town existed from the late 1800s until the late ’50s, when the city and media began using false stories peppered with racist stereotypes to humiliate and remove residents in order to encourage suburban development in what is now the Grant Park area.

“I teach about racism in Canada,” says Forsythe. “I talk about how the Métis people were removed from Rooster Town — I am a descendent of Rooster Town — by the city. I talk about the new library and how audacious it is to name it after a politician and his wife. I’m sure Bill Norrie was a fantastic mayor, and his wife, too, but it should have been named the Rooster Town Library.”

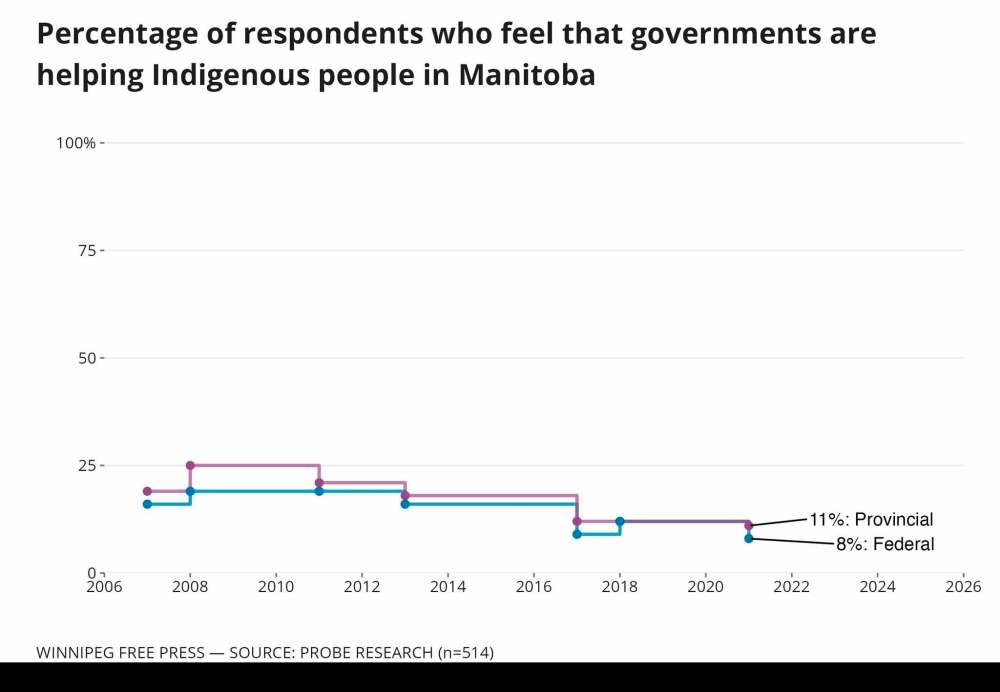

As for polling numbers that suggest Indigenous people are beginning to see some movement towards reconciliation among non-Indigenous people, Forsythe says she sees a difference in how governments treat Métis people.

“I don’t know if I agree — especially for the Métis nation — with the move towards reconciliation, because the (provincial) Conservative government is not moving towards reconciliation, but I see it at the federal level with them recognizing we have self-government,” she says.

“And, with this summer’s uncovering of over 6,000 bodies of children, about the issues around residential schools and the children being taken from their families, people now realize something happened.

“That’s the first step; acknowledgment is Step 1.”

The Probe survey found about one-third of Indigenous people believe Canadians are starting to understand the true impact of residential schools and are moving towards reconciliation.

Back at Kelvin, Miyawata has her sights set on training to become an oncologist.

“My grandma was one of the first Indigenous nurses; she won a Governor General’s Award for what she did in the health field,” the teen says.

“I’m very interested and driven to make change.”

kevin.rollason@freepress.mb.ca

The survey

Probe Research has conducted eight Indigenous Voices Omnibus Surveys since 2004.

For the latest one, Probe surveyed 514 people who identify as First Nations, Inuit and Métis between July 27 and Aug. 25. The data collection was set up to get a representative sample of both on- and off-reserve residents and Métis, First Nations and Inuit respondents, as well as residents in Winnipeg, the North and the province’s southern and western regions.

The survey was also conducted during the time four significant events occurred: the discovery of 215 graves at the former Kamloops Indian Residential School — the first of several such findings at former residential school sites; the resignation of Eileen Clark, from her cabinet role as Manitoba’s Indigenous and northern affairs minister after then-premier Brian Pallister made controversial remarks about colonial settlers’ “good intentions”; the toppling of statues on the Legislative Building grounds; and the recent federal election.

The margin of error for the survey is plus or minus 4.38 per cent 19 times out of 20.

Kevin Rollason is a general assignment reporter at the Free Press. He graduated from Western University with a Masters of Journalism in 1985 and worked at the Winnipeg Sun until 1988, when he joined the Free Press. He has served as the Free Press’s city hall and law courts reporter and has won several awards, including a National Newspaper Award. Read more about Kevin.

Every piece of reporting Kevin produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Monday, October 4, 2021 4:36 PM CDT: Laura Forsythe is a lecturer at the University of Winnipeg.