For reconciliation to succeed, truth must be learned

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 29/09/2021 (1532 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

In the two-step process that is truth and reconciliation, it’s tempting to rush to reconciliation and skip the first step of owning truths that can hit uncomfortably close to home. That would be false reconciliation.

The truth of how Indigenous people have been, and continue to be, mistreated by a dominant culture can be daunting. For some people, learning to regard themselves as settlers can be an unsettling experience. It’s necessary, however, to wrestle with these hard truths if subsequent efforts at reconciliation are to be built on a foundation of fact.

The closure of Manitoba schools and some government offices today to mark the inaugural National Day for Truth and Reconciliation will be well invested if people use the day to delve into truths about atrocities Canada has committed against Indigenous people.

Recent reports about unmarked graves on the former grounds of so-called Indian Residential Schools seem to have grabbed the public imagination, but a genuine quest for the truth will go deeper than understandable feelings of sympathy for the long-deceased children and their families.

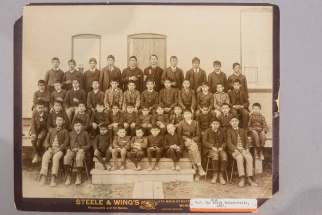

The residential schools, including 19 such facilities in Manitoba, were an institutional effort to erase the culture and identities of Indigenous people by robbing the next generation of their language, identities and family influence.

The residential schools, including 19 such facilities in Manitoba, were an institutional effort to erase the culture and identities of Indigenous people by robbing the next generation of their language, identities and family influence.

If such shameful goals seem surprising, it’s because accounts of the calculated strategy implemented by the federal government and Christian churches were absent from the history texts that educated most of us through several generations.

Also relatively new in the public consciousness is the way in which Indigenous people were driven from their land. It has become increasingly commonplace in Manitoba for events and organizations to recite acknowledgments that the land on which they stand was never properly ceded by Indigenous occupants to the colonizers who seized it with trickery and military force.

Likewise, Manitobans who can trace their ancestry to the original European settlers might recognize the home lots acquired by their forebears were a good deal for them but traumatic punishment for Indigenous people consigned to outback reserves on land that was often undesirable.

Uncomfortable truths, yes, but they are essential to accept if attempts at reconciliation will ever have lasting credibility. Understanding the history of land grabs, residential schools and the repressive provisions of the Indian Act are key to understanding the present. Such mistreatment led to dysfunction that is passed down from generation to generation, resulting in the social crises that leave an unacceptably high proportion of Indigenous people requiring social supports, consigned to homelessness or wasting away in Manitoba penal institutions.

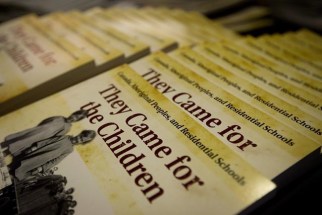

Such stark truths are outlined in the watershed report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission released in 2015 but, realistically, not every Manitoban will personally study the seven small-print volumes of this significant opus.

Locations where the truths are more easily accessible — all are open to the public today — include historical Indigenous exhibits at the Canadian Museum for Human Rights, the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation on the University of Manitoba campus, and the Winnipeg Art Gallery, which includes the new Inuit art centre Qaumajuq. Also, on television today, APTN will air a full schedule of related programming and CBC will broadcast, without commercials, an hour-long prime-time special presenting the perspectives of Indigenous people affected by the tragedies of residential schools.

As former senator and TRC head Murray Sinclair has said, reconciliation will take generations. But this inaugural holiday presents an opportunity to learn the facts. We eventually need to own the truth, but first we need to know it.

History

Updated on Friday, October 1, 2021 12:20 PM CDT: Corrects typo