Connecting with context, compassion Archivists, elder at National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation work to empower long-suffering Indigenous communities with carefully preserved, painful evidence of their trauma's origins

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 29/09/2021 (1531 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

The old stone house sits on the northern edge of the University of Manitoba campus, overlooking a bend in the Red River. Inside the house is a room lined with gifts given to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission: an eagle staff, a poem from a residential school survivor, a painting of a wolf affixed to a frame of soft leather.

It is here, at a long table lit by the late-afternoon sun falling through the window, that Sylvia Genaille sits, resting her fingers on a white folder. Beside her is a cardboard box filled with dried yarrow and sage, medicines harvested from the garden outside and used to smudge the folder before it is sent away. A cleansing.

“That will clean up any negative energies around here, because sometimes we really need that,” says Genaille, an Anishinaabe elder.

There is so much pain in these records; but in the act of collecting them and sharing them with those to whom they belong, there is also hope. And as Canada prepared to mark the National Day of Truth and Reconciliation on Sept. 30, a new federal day of observance, it is important to know how this knowledge is preserved.

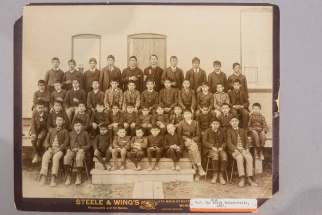

The records inside the folder Genaille holds were chosen according to what was requested, pulled from the nearly 200 terabytes of digital data stored here, at the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation. There’s a photo from 1920, of children standing in ordered rows; another photo almost the same, but taken decades later.

These are the children of Tk’emlúps, the children taken to the Kamloops Indian Residential School, which was once among the largest such institutions in Canada. It’s at the school’s site, near where these photos were taken, that the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc First Nation found 215 unmarked graves in the spring.

Images like these, they’re propaganda, archivist Jesse Boiteau says. That’s how you have to understand them: as advertisements, created by the churches in a bid for more government funds. They don’t tell the truth of residential schools on their own; for that, you need context, and collecting and preserving context is what the NCTR does.

The NCTR opened at the U of M in 2015, born out of an agreement to create a repository for all of the records and testimonies gathered during the TRC’s mission to document the truth of residential schools. Today, it holds records drawn from more than 150 different sources, from colonial paperwork to the testimony of survivors.

Boiteau was working at home the day the news about the graves broke. He was not surprised by the discovery; the existence of unmarked graves had long been attested by survivors. But he thought about the names on the NCTR’s memorial register, of the children who never came home; he wondered which of them might lie in those graves.

”It took something like this to finally get through to people.” – Jess Boiteau

And he thought about all the children not listed on the register, because their deaths were never recorded by colonizers who ran the schools. After that, he started thinking about the survivors who had spent decades telling Canada what they knew, only to find that few were interested in hearing them.

“It took something like this to finally get through to people,” Boiteau says.

The discovery at Tk’emlúps would change his work, though. As the news spread and other communities prepared to make their own site searches, the NCTR received a surge of records requests. In an average year, the centre fulfils about 200 such requests; Boiteau estimates they received nearly as many in June alone.

“We sort of expected it to be a temporary spike, but nothing has slowed down for us at this point,” he says.

It wasn’t just records requests, either. More survivors have come forward, empowered by the national discussion to give their own story to the NCTR’s archives. To meet this rising demand, the NCTR has added staff, and they triage the requests: those from survivors and communities are fulfilled first, media after.

”With the discovery of the children, there’s been sort of a reawakening. People are now ready to tell their story, so we need to be responsive to that. That’s multifaceted. It involves outreach, research, archives. We’re quickly working to find the right mechanism to accomplish that.”- Jess Boiteau

“With the discovery of the children, there’s been sort of a reawakening,” Boiteau says. “People are now ready to tell their story, so we need to be responsive to that. That’s multifaceted. It involves outreach, research, archives. We’re quickly working to find the right mechanism to accomplish that.”

Part of that work, Boiteau says, means evolving how the NCTR sees its relationship with communities impacted by residential schools. Work at the centre has always been somewhat dynamic, he says, changing as it grows; recent months have underscored how key it is to let communities take the lead in naming the support they need.

“The biggest lesson would be to, rather than imposing our way of approaching archives, actively listening to the needs of survivors and communities, and then taking that back and implementing it within our systems,” he says. “That’s probably been the biggest learning curve, and something that we’ll continue to learn from.”

That approach in itself represents a shift, in how institutions like this work. Boiteau, who is Métis, has worked for the centre almost since the beginning; in 2017, he delivered his master’s thesis on the “living archive” that is the NCTR. It is a “dream job,” he says, a chance to put emerging ideas about decolonizing archives into action.

What exactly does that look like? Boiteau pauses for a moment. He doesn’t want to go too deep into archival theory. But then again, understanding a little of that is key to understanding how the NCTR approaches what it does, so it’s worth digging at least a little way in.

Here’s an example. In archival work, records are given descriptions. There’s a description of the record itself — what it is, who’s in it — but also a description of what archivists call the record’s authority. Traditionally, a listed authority is the organization that created the record: a government, for instance, or a convent.

At the NCTR, all records are described under the authority of the community, which is represented in the records or even the individuals within them. It’s a shift that is both practical and symbolic, a statement that the records belong, above all, to the survivors and then to the generations of Indigenous people who come after.

“It’s more of a human way of approaching the profession,” Boiteau says. “Rather than viewing individuals in the records as subjects of the records, we’re actually viewing them as actors.”

Archiving this way also has a practical purpose: it allows the NCTR to link together every record that tells a given community’s story, from church paperwork to survivors’ testimonies. The goal is to someday create an online portal, where people can, with a few clicks, pull up a trove that shows their community’s history, and their own.

In this vision, the NCTR is less the brain of residential school knowledge in Canada, but more like a heart, all these stories of lives pulsing through lines of connection, spreading out through the continent, carrying truth to the people and places who were told, for so long, that the truth of what had been done to them didn’t matter.

The biggest challenge now, Boiteau says, is filling in the gaps in the records, so that all the truth can flow forth. This is an uphill battle; despite years of effort to collect and preserve as much as possible, the archives are not complete. There are still an unknown number of records out there, scattered across government and church archives.

To the NCTR’s archivists, the importance of filling in those gaps is not an academic question. The people who come to them looking for records are survivors, or descendants of survivors; they are looking for their own story, or that of their siblings or grandparents. Being able to see and hold these documents may be a key part of their healing.

So what happens when a survivor comes looking for records, but none are found?

Boiteau leans against the wall of his office and sighs.

“It sucks,” he says. “It’s about the worst feeling.”

So that’s the next part of the work, he says — tracking the rest of it down. That, and also gathering more testimony to add even more knowledge, to bring even more truth to the collection, to safeguard even more of that context essential to understanding what happened and how it must never be allowed to happen again.

”Any new perspectives of anyone who’s been touched by the residential school system, we’re always open to accepting those…. There are all these gaps in the colonial record that often times can only be filled by survivor’s voices.” – Jess Boiteau

“It’s important in the immediate, but also for generations, as well,” Boiteau says. “Any new perspectives of anyone who’s been touched by the residential school system, we’re always open to accepting those…. There are all these gaps in the colonial record that often times can only be filled by survivor’s voices.”

For now, they have a package of records to send out. At the table, Genaille calls for help from Trinity Tomm, an office assistant; the elder has been teaching NCTR’s staff about the traditional ways, the way she was once taught by elders herself. Tomm takes the folder and wraps it in red cloth, taking care to ensure the edges are neatly lined up.

Thus wrapped, the records are ready to be sent to the community that sought them. The NCTR’s executive director, Stephanie Scott, will hand-deliver them to Tk’emlúps the next day. Records are usually sent out on a USB stick, so this opportunity for a face-to-face exchange is a welcome one.

Genaille lifts the folder gently. She has been at the NCTR since its inception, helping support survivors and offering her knowledge to staff. When she started, she would look for her parents in the photos of children at the Pine Creek residential school, which they had survived. So far, she has not found them.

“I don’t know if that’s going to happen,” she says, quietly. “But I’m still hopeful.”

The elder is actually retired now. Still, she keeps coming back to help, and says she will always be there when they call her. The feeling she gets working at the centre, she says, is one she cannot even put into words; but what they have built here is more than a place for archives and records. It is, above all, a place of connection.

“My love is here. My family’s here,” she says. “And I don’t think I’ll be going anywhere anytime soon.”

melissa.martin@freepress.mb.ca

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.