Each of us must work to reverse damage of residential schools

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 29/09/2021 (1531 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

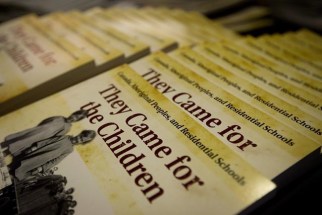

The federal government went to great lengths to cover up the deaths of Indigenous children in residential schools throughout Canada’s history. Records were destroyed, poorly kept, or deaths were not documented. The question Canadians should reflect on today, especially on the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation, is why federal officials were so eager to conceal those atrocities.

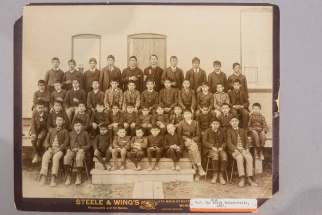

Throughout much of the late 1800s and 1900s, Indigenous children were taken from their families and forced into unsafe, unsanitary residential schools that were breeding grounds for deadly communicable diseases, such as tuberculosis. Thousands of Indigenous children died in those schools, mostly from disease, but also from other causes, including accidents and suicide. Some ran away to flee sexual, physical and psychological abuse at the largely church-run, government-funded schools. Many remained missing.

There were varying numbers of deaths at the schools. What was common at all of them, though, was how the federal government tried to ensure no paper trail was left behind.

Until 1915, the Department of Indian Affairs published summaries from residential school principals that detailed the health conditions in schools, including the number of deaths. But once residential school deaths started to rise in the early 1900s, the department — without explanation — stopped publishing the information.

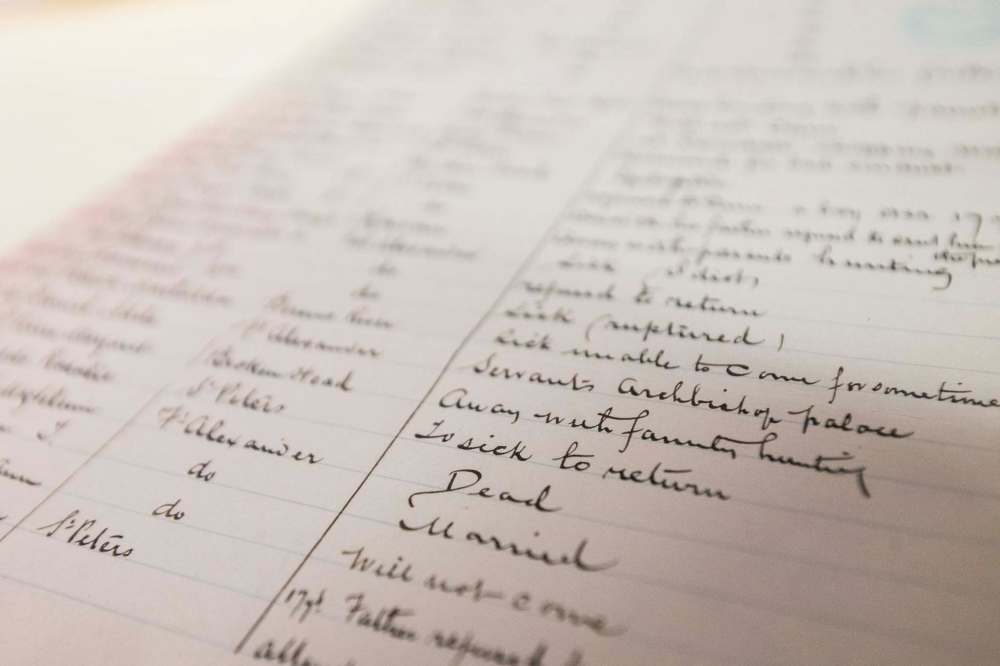

Some records were kept after that, but they were sporadic and grossly incomplete. In many cases, the names of the children who died were not recorded; in about half the cases, the cause of death was not documented. Some deaths were likely never reported.

Many of the records no longer exist. Research from the 2015 Truth and Reconciliation Commission report shows 200,000 Indian Affairs files were destroyed from 1936 to 1944. In 1957, the Department of Indian and Northern Health Services was instructed to destroy all records, including those pertaining to medical services, requests for treatment and hospital admissions, after two years. There was a concerted effort to leave behind as little paperwork as possible. It’s as if someone was trying to hide something.

There were whistleblowers in the early 1900s who tried to alert the public, but their reports were covered up or ignored. Among them was Dr. Peter Bryce, chief medical officer for Indian Affairs, who performed regular inspections of residential schools. His findings were consistently ignored. In one 1907 special investigation of 35 residential schools in the three Prairie provinces, Bryce found almost one-quarter of children had died. His recommendations on how to improve the health conditions in residential schools were rejected.

In 1914, the federal government, without a satisfactory explanation, informed Bryce that his annual inspection reports were no longer required.

For decades, that was the federal government’s pattern when it came to residential schools: to suppress the ugly truth behind Canada’s systematic attempt to destroy Indigenous people. The federal government didn’t want its genocidal methods exposed. It wasn’t how politicians wanted Canada to portray itself.

But that truth is now emerging, thanks to the work of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and others. Non-Indigenous Canadians are relearning their history and discovering that the birth of their country and the wealth and privilege they enjoy today came at the expense of those who were here before them. Canada saw Indigenous people as obstacles to be shoved aside; their kids sent to facilities with no health and safety standards, where if they died, the government often didn’t care enough to record their names, notify their families, or provide them with a proper burial. That is Canada’s history.

The National Day for Truth and Reconciliation will help highlight that. But it’s something Canadians will have to confront and work on daily if they want to help reverse the damage caused by the atrocities this country tried so hard to cover up for so long.

tom.brodbeck@freepress.mb.ca

Tom has been covering Manitoba politics since the early 1990s and joined the Winnipeg Free Press news team in 2019.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.