Bombers committed to listening at the goal line Club welcomes Indigenous perspectives into huddle to strengthen community bonds

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 29/09/2021 (1532 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Brandon Alexander has first-hand experience of what it’s like to be treated like a second-class citizen.

The Winnipeg Blue Bombers safety was 17 when he and a friend, driving home from the city fair in his dad’s Cadillac, were surrounded by dozens of cops, their shotguns drawn and aimed at the two teen boys.

Alexander was just minutes from his home in a safe and respected community in Orlando, Fla. He was asked six or seven times where he had been and what he was doing; each time it was as if his answer — which Alexander relayed calmly, something his parents pressed on him to do if he was ever pulled over by police — didn’t matter. They never asked for identification or if they could search his vehicle, but they did so anyway.

When the police noticed an empty gun holster in the car — Alexander’s dad owns a registered firearm but purposely removed it whenever his son borrowed the vehicle — the intensity heightened. Overwhelmed by what was unfolding, Alexander’s pants started to slide down as cops were searching him, creating a natural reaction by the teen to pull them back up.

“I guess they thought I was reaching for a weapon,” Alexander wrote in a detailed account of the event shared on the Bombers website following the tragic murder of George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer in May 2020, “and one of the officers ended up putting his shotgun in my back and another put his handgun in my face and said, ‘If you move again, I will fire.'”

He added: “All I could think was, ‘Am I going to make it home?'”

As neighbours emerged from their homes, the police, after a brief discussion, decided to let the boys go. But still followed Alexander all the way, including one officer challenging him about where he lived even as he walked up the front steps.

Though a traumatic experience, Alexander also knows it isn’t unique. The maltreatment of Black people in the U.S., particularly by law enforcement, has been well-documented. Being judged and stereotyped because of skin colour is commonplace for African Americans.

“It’s a lot– it’s a lot to talk about, it’s a lot to hear, it’s a lot to carry and there’s a lot to say. I believe that more of these conversations — tough conversations — will make it just a bit easier to do that.” – Brandon Alexander

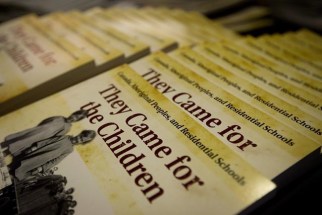

Having lived in Winnipeg for three football seasons, Alexander sees parallels between the negative treatment by some in the U.S. against the Black community and how Indigenous people can be ostracized here in Manitoba. As Canada marks the first ever National Day for Truth and Reconciliation, a day of observance recognized by the federal government to honour the lost children and survivors of residential schools and their families and communities, Alexander stresses the power of dialogue.

It’s only by talking that we can understand one another.

“It starts with a conversation, but this is not about one side just trying to get it, it’s about all sides coming together and being able to have that tough conversation,” Alexander tells the Free Press. “It’s a lot — it’s a lot to talk about, it’s a lot to hear, it’s a lot to carry and there’s a lot to say. I believe that more of these conversations — tough conversations — will make it just a bit easier to do that.”

Alexander has never witnessed racially motivated hate against Indigenous people but has heard about it, which has caused him to feel a palpable tension in the province. He’s not surprised he hasn’t witnessed such behaviour, noting that if someone were to visit the U.S., there’s little chance they would encounter police brutality.

“I’ve walked by signs, buildings with messages painted on the walls that talk about what’s going on with Indigenous people and women getting killed,” he says. “So, it’s out there in the forefront but you don’t see the underlying issues, you don’t see it happening in front of your face. But that doesn’t mean it’s not happening.”

Alexander is proud that the Canadian Football League and, particularly, the Bombers, have embraced the day of observance. In the days both leading up to and following Thursday’s observance, there have been and will be educational seminars for employees, game-day ceremonies, in-stadium videos and moments of silence.

Each of the nine CFL teams have come up with their own way to recognize the day, with the Bombers using their home game against the Edmonton Elks on Oct. 8 to showcase months of hard work happening behind the scenes here.

Winnipeg and Edmonton will be wearing special orange jerseys during warm-up, which will then be auctioned off and the proceeds donated to a charity of each team’s choice. The Bombers have gone with the Winnipeg Aboriginal Sport Achievement Centre, a foundation that helps to remove barriers for thousands of children annually and is Canada’s largest employer for Indigenous young people.

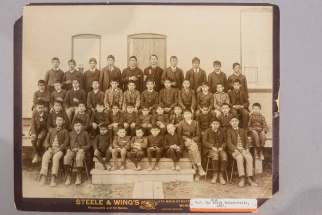

A Manitoba-inspired Indigenous logo has been designed and will be unveiled next week on the pre-game jerseys and game-worn helmets. There will be pre-game and halftime ceremonies honouring special guests, including words from a residential school survivor and the presentation of a star blanket featuring the Bombers’ blue and gold colours to the team. “Every Child Matters,” a call to action that has marked the dark legacy of residential schools, will be painted on the field.

The biggest endeavour, spearheaded by Exchange Income Corporation, involves welcoming 1,000 members of the Indigenous community from various parts of the province. Each will receive an orange T-shirt with the Bombers’ W logo and dinner before kickoff. There will be honours announced throughout the game.

“I just can’t imagine what’s occurred with the Indigenous community and I think it’s important we all learn and understand that,” says Wade Miller, Winnipeg Football Club president and CEO. “I want my son to understand what occurred and how we ensure that never happens again. I don’t think you ever heal from that entirely, but how can we just do better?”

Oct. 8 won’t be the first time the Bombers honour and welcome the Indigenous community. Since 2017, the team has flown in children from First Nation communities to every home game, giving them a unique experience that includes interacting with players.

The relationship between the football team and the Indigenous community started to take root in the summer of 2015. Brayden Harper, a 20-year-old intern from the Asper School of Business at the University of Manitoba, was tasked with developing relationships with Indigenous communities.

On the eve of the Bombers’ first pre-season game, Harper pitched to Miller the idea of reading a statement at every home game acknowledging that the Bombers were playing on traditional Indigenous and Métis territory. Harper had worked with Justin Rasmussen and Christine Cyr from the Indigenous Student Centre at the U of M to come up with the statement, which has been delivered prior to kickoff ever since.

That gesture set in motion a desire by the Bombers to further strengthen their relationship with the Indigenous community. The next step was obtaining the help of Niigaan Sinclair, an Anishinaabe professor of native studies at the U of M and a Free Press columnist. What began as an informal connection, with Sinclair providing advice and guidance on new initiatives, has since evolved into a more formal role; Sinclair is the club’s director of Indigenous relations.

“It helps that people who are in any organization anywhere, like any corporate entity but particularly sports teams, that when they show commitment to issues and they bring attention to those issues with the power and privilege that they have, it makes people listen,” Sinclair says.

“It makes people understand that that this isn’t something that’s optional, and the more that we can bring attention to the issues of how important it is that we all live together and we should live respectfully and ethically, that’s what I think is the key here.”

Over the years, the Bombers have come up with different ways to provide support.

“It makes people understand that that this isn’t something that’s optional, and the more that we can bring attention to the issues of how important it is that we all live together and we should live respectfully and ethically, that’s what I think is the key here.” – Niigaan Sinclair

In 2016, as part of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s call to action on sports, the team created the Jack Jacobs Scholarship, named after the former star Bombers quarterback from the 1950s and member of the Canadian Football Hall of Fame who is also a Muscogee (Creek) Indigenous person. What began as one $500 scholarship has since expanded to two $5,000 scholarships, eligible to Indigenous high school students who plan on pursuing a post-secondary education and who have a passion for sport, a love for football and a commitment to balance between sports and academics.

This year, prior to the Aug. 5 home-opener, the Bombers had a flag-raising ceremony honouring the Treaty One Nation and the Red River Métis. The Treaty One flag represents seven communities — Brokenhead Ojibway Nation, Fort Alexander (Sagkeeng First Nation), Long Plain First Nation, Peguis First Nation, Roseau River Anishinabe First Nation, Sandy Bay First Nation and Swan Lake First Nation — and flies alongside the Métis flag on the Sky Deck flagpole on the south end of IG Field, visible at all events.

Sinclair has worked with Valour FC, the local pro soccer team also owned by the Bombers. He helped put together a shoe memorial acknowledging the many children who died attending residential schools at IG Field during the Canadian Premier League “bubble” tournament earlier this year.

All Bombers and Valour staff received a 90-minute presentation from Sinclair Wednesday.

“We try to do the right thing and we’re always going to listen and learn,” Miller says. “In order to make a difference, it’s important to listen.”

Brian Chrupalo knows well the power sport can have on a child. He’s living proof of what can happen when given an opportunity.

Chrupalo, who is Métis, can recall growing up in Manitoba Housing in the North End, where trouble often lurked nearby. To stay focused as a child, he immersed himself in sports, something he confidently says saved his life.

Fast-forward to today and he’s in his 28th year with the Winnipeg Police Service and has been a CFL field judge for years. He also works closely with the Bear Clan Patrol, including helping raise more than $1 million to provide food hampers during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Chrupalo, who acts as a designated liaison between the WPS and Indigenous communities, understands more than most the impact a relationship between the Bombers and First Nations people can have.

“There are a lot of role models in sport and in the CFL itself,” he says. “We have an opportunity and a responsibility to the community to be that spokesmodel.”

Chrupalo used his role as president of the Canadian Professional Football Officials Association to push for referees to wear orange pins in Week 1, a gesture to honour the Every Child Matters movement. The pins, which were designed by Tamara Muswagon from Pimicikamak Cree Nation, will soon be worn by Winnipeg police officers.

“There are a lot of role models in sport and in the CFL itself. We have an opportunity and a responsibility to the community to be that spokesmodel.” – Brian Chrupalo

Chrupalo is encouraged by what the CFL and Bombers have done in recent years to bridge the gap with Indigenous communities and points to their Diversity is Strength campaign from 2018 to suggest an effort and understanding from the league is more than just lip service. He knows there’s a lot of work still to be done, but he’s hopeful that the momentum building around movements aimed at supporting Indigenous people will continue to grow over time.

“It’s helping bring attention to what’s happened — the atrocities — and that’s a positive. It’s good for people to be able to look and say, ‘Yeah, something horrible happened,'” Chrupalo said.

“I don’t want to be the person that gets talked about in 100 years, that we made a horrible decision. I don’t want to be that person.”

jeff.hamilton@freepress.mb.ca

twitter: @jeffkhamilton

Jeff Hamilton

Multimedia producer

After a slew of injuries playing hockey that included breaks to the wrist, arm, and collar bone; a tear of the medial collateral ligament in both knees; as well as a collapsed lung, Jeff figured it was a good idea to take his interest in sports off the ice and in to the classroom.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Wednesday, September 29, 2021 7:09 PM CDT: Adds missing word to sentence about being pulled over by police