The outsiders The story of Rooster Town: a Métis shantytown on the city’s fringe that struggled as the city prospered By: Randy Turner Posted: Last Modified: Updates

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 29/01/2016 (3689 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

They were invisible then; they are invisible now.

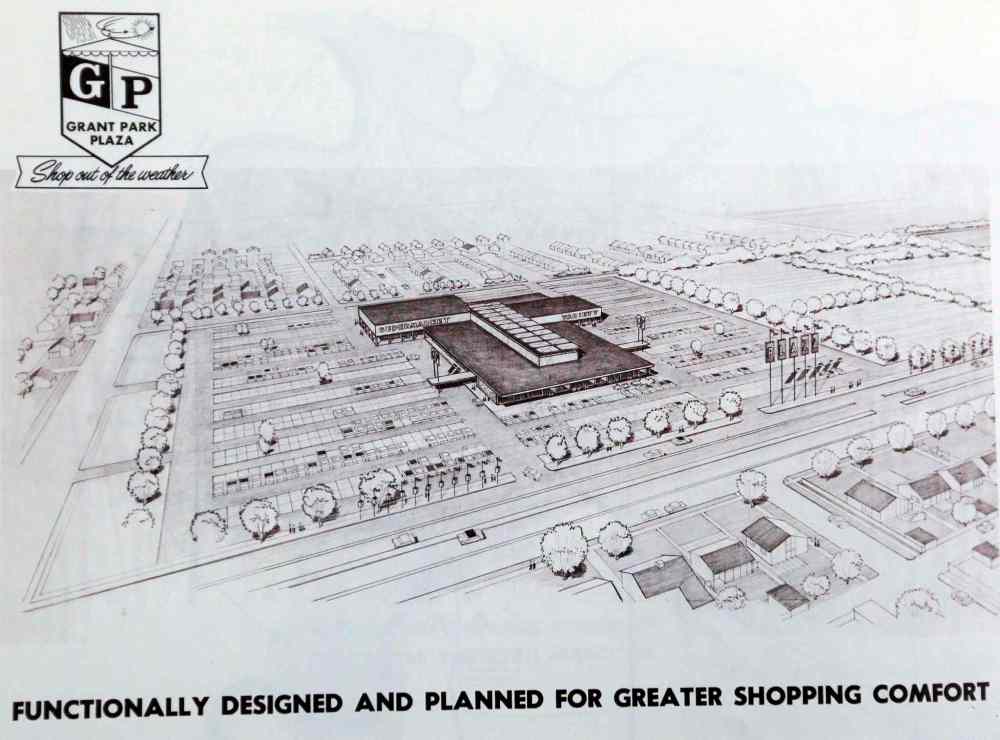

Yet the little-known legacy of Rooster Town — a long-since displaced community of shanties bulldozed to make way for Grant Park Shopping Mall in the late 1950s — remains ingrained in the city’s character, according to historians.

In fact, it was just last week that Winnipeg Mayor Brian Bowman, on the anniversary of a Maclean’s magazine article declaring Winnipeg the most racist city in Canada — held a public forum to pledge aboriginal accord. This would be the year of reconciliation, he said.

Bowman, it should be noted, is the first mayor of Métis heritage in the city’s history. This is not of little significance, given the fractious and often violent relationship between Métis and European settlers dating back to the deadly conflict of the Riel Rebellion that began in 1869, and has permeated the city’s psyche for generations hence.

From the 1880s to the early 1960s, Rooster Town was a living, breathing weather vane of that pockmarked history.

Yet few Winnipeggers are probably aware the land now occupied by the Grant Park Shopping Centre, Pan Am Pool and Grant Park High School was once home to a disparate and desperate clutch of families who mostly lived in shacks built from found wood.

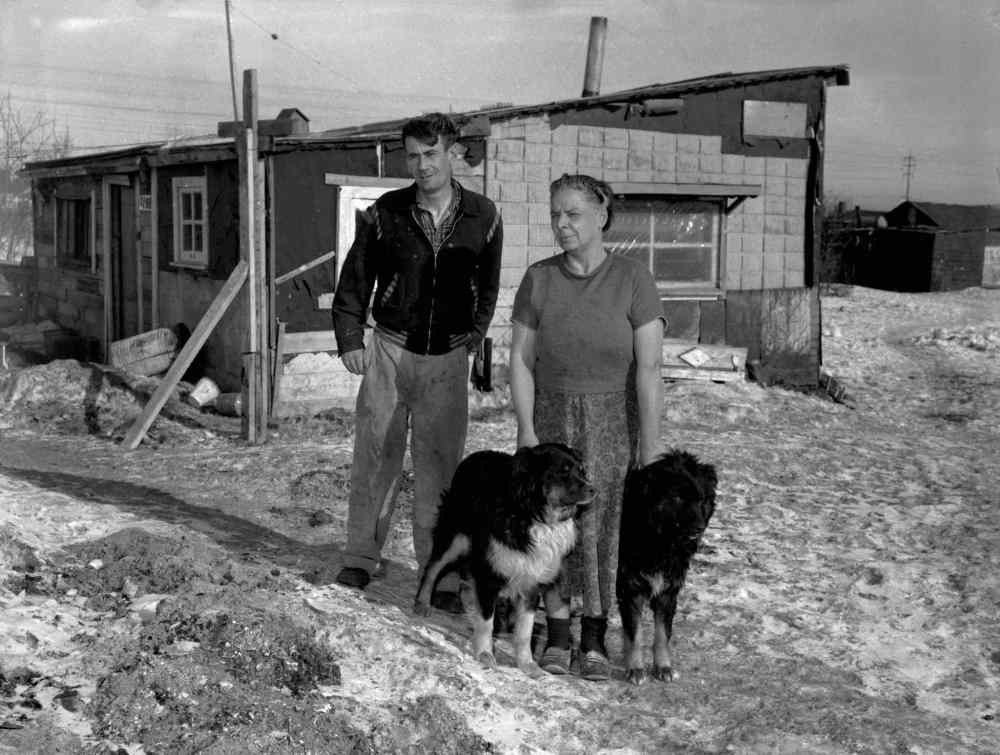

They had no running water, no sewer, no lights, no roads. Their homemade shanties were dotted in the bush just south of what now is Grant Avenue.

“They were intensely poor,” said Evelyn Joy Peters, professor of urban geography at the University of Winnipeg, who specializes in Métis and First Nations people in city environments. “They faced enormous prejudice. But they were trying to make a better future for their kids, which they did.”

Peters, a Canada Research Chair in inner-city issues, has spent the last three years working in collaboration with the Manitoba Métis Federation attempting to piece together the lineage of Rooster Town and its inhabitants. It hasn’t been easy.

“This is a community,” Peters said, “that only leaves behind marginal traces.”

The birth, existence and eventual disappearance of Rooster Town is telling, too. Not just as a testament to historical attitudes, but as a reference point to the issues facing the city and its aboriginal population today.

Consider the roots of Rooster Town. The original “settlers” were Métis who first arrived on the outskirts of Winnipeg in the 1880s, Peters said.

Many, if not all, had never received the land they’d been promised under the Manitoba Act, Peters said, so their goal was to find employment in the growing city, mostly seasonal jobs and hard labour.

They built shanties on land that had originally been purchased by speculators and abandoned, kept farmyard animals and tended gardens.

At first, the settlement went as far north as Corydon Avenue, but the inhabitants were continually pushed south as the city expanded.

“As the city moved south, the rooster towns loaded up their scrap wood shacks and moved on, further into the prairie,” John Dafoe wrote in a April 1951 Free Press article on the community.

“As they moved, their place was taken by some of Winnipeg’s most elegant homes.”

The population peaked in the 1930s, with “several hundred” residents — there was never a definitive population reported — who had constructed their homes largely from dismantled boxcars from the nearby Canadian National Railway yard. The community stretched from Stafford Street on the east to Lindsay Street on the west.

There were no streets in Rooster Town, just a series of trails between shacks that were largely hidden in the bush.

According to legend, the name Rooster Town was derived from the fact many residents owned chickens. Other unsubstantiated reports claimed the nickname originated from illegal cockfights that were said to be held in the community.

“Winnipeggers used to go out there to bet on the birds,” claimed one front-page story published in the Free Press on Dec. 20, 1951.

“We don’t exactly have an address here,” resident A.J. Cloutier told the reporter. “We generally call it about 1148 or 1150 Weatherdon Ave.”

But then press coverage of Rooster Town was never flattering. The Free Press story in 1951 was headlined: Village Of Patched-Up Shacks Scene of Appalling Squalor.

In the story, it was pointed out that residents had only one source of water, a town pump located more than a kilometre away. Residents either hauled water by the barrel, using horses, or carrying cream cans by hand. Meanwhile, between “12 and 24” family members lived in one- or two-room shacks.

As a result, Rooster Town children contracted skin disease, chicken pox and whooping cough at frightening rates.

“They have no plumbing, no sewers and are crowded into these little shacks and sleeping, in some cases, four to a bed,” school trustee Nan Murphy was quoted as saying.

“The children are good at school, but the parents have no moral responsibility. They are shiftless and even when clothes and things are given to them, they sell them.

“It has been going on for years,” she concluded, “And it has cost unlimited funds in health and welfare.”

Lawrie Barkwell, co-ordinator of Métis Heritage and History Research at the Louis Riel Institute, who is working with Peters on the Rooster Town project, called this tone of reporting both typical and inaccurate.

“That’s how they’ve been portrayed, as trash,” Barkwell said. “If you read the newspapers of the day… It’s like we’re going to the zoo to take pictures of people in Rooster Town. It’s was like, ‘Look at this poverty. It’s these people’s fault that they’re living this way. We’ve got to get them out of here.’ ”

Rooster Town residents were never welcome in Winnipeg to begin with, said retired University of Winnipeg history professor David Burley, who described the treatment of residents as “municipal colonization.”

“Just the idea of what a city was didn’t recognize the indigenous presence as legitimate,” said Burley from his home in Hamilton.

Burley has done his own extensive research included in a paper dubbed, Rooster Town: Winnipeg’s Lost Métis Community, 1900-1960, which in 2003 was presented as an exhibit at the Millennium Library.

That research, he said, concluded Winnipeg itself was founded on land that was once occupied by First Nations and Métis settlers. They were replaced, he said, and never recognized as urban dwellers.

“Through its history, Winnipeg has seldom been hospitable to aboriginal people, either those whose presence predated the city’s incorporation in 1874 or those attracted afterwards by its opportunities,” Burley wrote. “Being Métis in the city through much of the 19th and 20th centuries meant being subject to racism and even violence.”

Burley cites a Free Press description of Métis in 1941 as “having the instincts of the Indian thinly coated over by certain sophistications of the Aryan. He is difficult of assimilation into white culture. He stagnates in the hovels on the fringes of little suburban centres.” (Remember, this was during the Second World War)

A study of the province’s aboriginal population in 1956, conducted by Jean H. Lagasse, identified 26 of these fringe settlements, including Rooster Town. Lagasse said poor living conditions and the “absence of any social pressure to promote ambition or accept moral behaviour” created a “slum mentality.”

“It made it easy to say, ‘You have no place here. You have no space. They’re not our concern,’ ” Burley said.

“They ended up marginalizing them both physically and socially. They were pushed to the edge of the city or beyond the town limits. And many of the kinds of services that Winnipeg residents of European background had, just weren’t available for them — sewers, water.”

Burley said the fringe communities were largely ignored and the end results of poverty and lack of services festered in isolation — but only for so long. The deterioration of housing in Winnipeg became the subject of the April 22, 1944 issue of Flash, a Toronto-based magazine, which declared, “Winnipeg can lay claim to the dubious distinction of being the most backward city in Canada in regard to housing and sanitary conditions.”

Just imagine: Winnipeg being called out by a Toronto-based magazine for the socio-economic of its indigenous citizenry. Sound familiar?

Clearly, Burley concluded, the pattern of neglect and isolation historically visited upon the city’s aboriginal population has been an abject failure.

In fact, Burley said that up until the last few decades, the assumption was aboriginal population growth in the city has resulted from First Nations residents flooding into the city.

“But indigenous people have been living in the city right from the beginning,” he said. “It’s been a constant presence. People ignored it, tried to remove it, but that presence has always been there.

“I think the idea that aboriginal people just don’t belong in the city is so deep. They don’t see the aboriginal presence right in front of them.”

Peters said one of the goals of her project is to challenge the falsehoods surrounding Rooster Town.

“It’s a part of urban history that’s invisible. I mean, some people remember but people have an idea that only the shacks were Rooster Town and only the squatters were Rooster Town,” she said.

“They don’t realize that there was a larger community. There are myths about it, and it would be nice to write about what really happened.”

What are the myths?

“That they were all squatters,” Peters said. “That’s not true. Many were on their own land. And if they owned the land, they paid taxes. Even some who were squatters were paying taxes on their houses. Even though they had no sewage, no running water, no streets, no lights.”

Were they poor? Damn straight. Most were large families trying to subsist on income of $200 to $300 a month.

“Just the kind of resilience there was amazing,” she said. “Some people were on welfare, but not the majority.”

The only recorded history of Rooster Town in newspapers of the day involved either abject poverty, violence or the prevalence of homemade liquor and gambling. Yet even Dafoe’s 1959 article — in which an assistant director of the city’s welfare department, Gerald O’Brien, described the community as living “Indian style” — contained its own contradictions.

After the city official commented on the parties that got “pretty rough,” the author noted “residents caused little trouble in the rest of Winnipeg.”

The Dafoe article noted truancy was a problem among the children, but juvenile delinquency was no worse than in other areas.

“One reason, I think, is that the families were very close-knit,” O’Brien explained. “They may be 10 people living in the space of two rooms, but grandma always had her corner.”

The beginning of the end for Rooster Town came in the late 1950s, when plans were unveiled for the Grant Park Shopping Centre and the adjacent high school. Suburbia was coming with a vengeance.

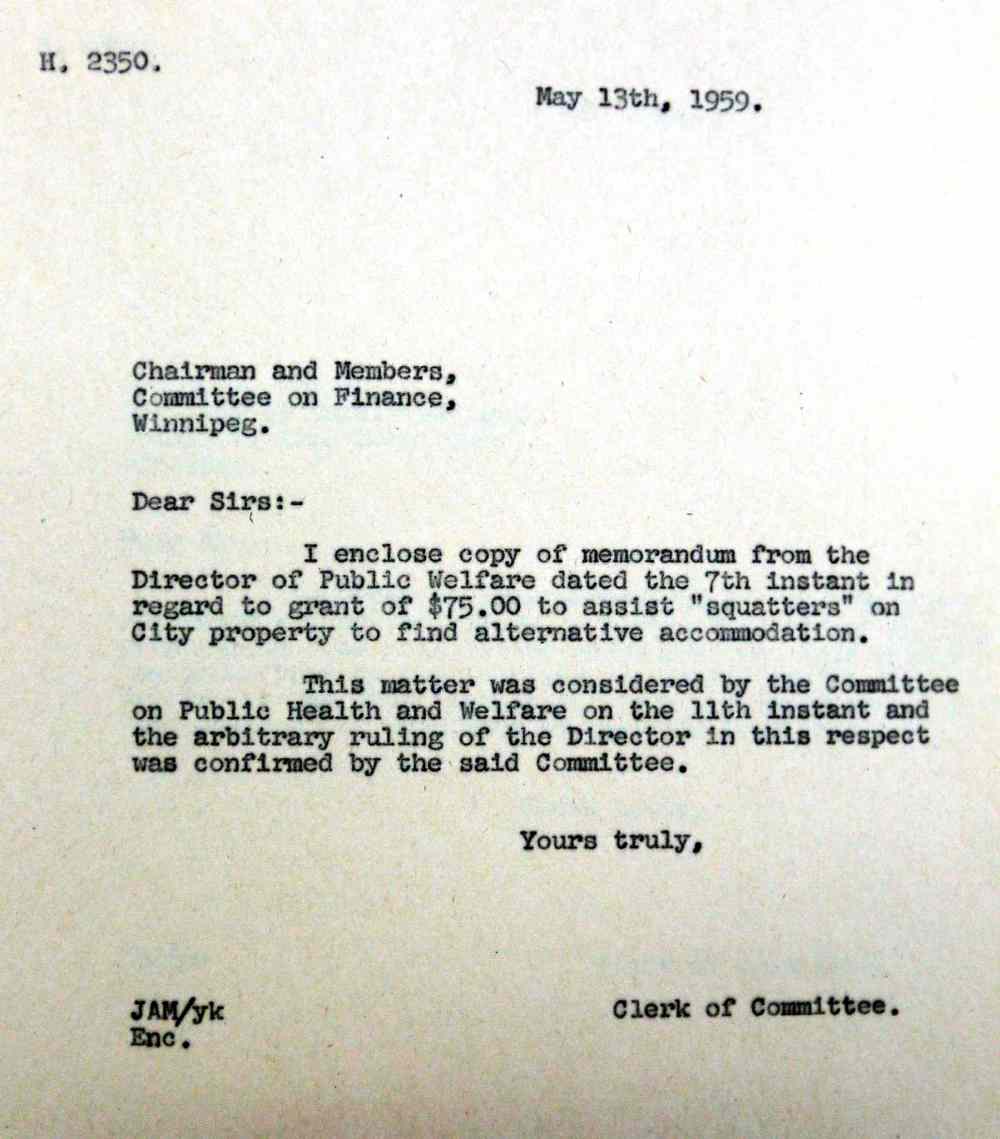

At the time, only 14 families remained. They were offered $75 by the city to vacate their property.

In his 1959 story, headlined Rooster Town is Dying — But It Had Its Wild Days, Dafoe noted: “Now there’s no place to go. A new subdivision forced many of them out two years ago. They moved into slum areas of Winnipeg and most of them are still there. The last 14 families will likely do the same. By summer, Rooster Town will be gone. But the problems of the Rooster Towners, and of the city which must care for them, remain.”

Dafoe was prescient. As the suburbs began to grow, the lower rents and houses could be found in the inner city. So the upwardly mobile left, only to be replaced by low-income residents.

“It’s almost like the city got turned inside out; that the people who lived downtown moved to the edges and the people on the edges moved downtown,” he said. “The same as now, really.”

Added Barkwell: “Social planning wasn’t, ‘We have to find more housing for these people.’ It was, ‘We have to get them out of here so we can build this school, we can build this shopping centre.’”

Rooster Town went out with a whimper. A Free Press article dated April 8, 1959, said the residents left “without despair or bitterness, without excitement, without what could even be called resignation. They were just moving.”

“We’re not going to put up any fight,” said Ernest Stock (WFP, March 4, 1959).

Added Mrs. Rose Halchacher, who lived in a two-room shack with her husband and eight children: “My husband is a veteran. Maybe they’ll give us a veteran’s house… I wouldn’t mind moving if they find us another place with sewer and water as long as it’s not too far from here… If they don’t find us anything, we’ll just have to live in a tent.”

The remaining homes were bulldozed or burned. Rooster Town was no more.

There is no physical legacy of the community. But that doesn’t mean the sociological effects of Rooster Town, and what that represented to the aboriginal community, was as easy to erase.

Even back in 1959, Winnipeg Tribune reporter Bill MacPherson noted that at Rockwood School, when a teacher called for a group game and told the kids to join hands, “Nobody would dare join hands with the Rooster Town children.” This caused the reporter to opine: “Just what those little episodes can do to youthful personalities can be left to the imagination.”

Burley has heard about what those “little episodes” can do.

He told the story of a Métis woman, now in her 50s, who attended Rockwood. “Her mother would scrub her children before sending them to school just so no one could ever possibly accuse them of being dirty. That was something that was a very important part of her childhood: the importance of being clean. Because being clean was the opposite of the stereotype many people had of Métis people.

“So, I think it’s a sore point. Many people still might not be ready to speak very much about it.”

Barkwell has also seen the negative effects.

“We’ve had kids whose fathers were kids in Rooster Town,” he noted. “And they said they never thought they’d own their own homes. Métis people are people that don’t own their own homes, their own land.

“The belief in the community was you can’t get an education; if you’re brown-skinned you’re just cycled through. The assumption is you can’t learn, and you’re not competent to make your own decisions or control expenditures. It’s this whole thing of devalued people.”

No wonder Lagasse’s study in 1958 found that fewer than one per cent of people interviewed admitted to being Métis, despite estimates that between one-eighth and one-quarter of all Manitobans at the time had some degree of aboriginal ancestry.

“If people had wanted to ignore it in the past, I think there ought to be some kind of willingness now to deal with the history. There’s a lot of learning that people in Winnipeg still have to undergo. Maybe there was a time when people just choose to ignore it.”

It affected the way indigenous people view establishment. “I think there’s mistrust and cynicism. Many of the people who experienced the racism of Rooster Town or elsewhere don’t want to deal with it because it’s so painful.”

Just how far attitudes have evolved is an open debate, and all the more reason, Peters and Burley agree, to keep the memory of Rooster Town alive.

“I think it’s changing,” Burley replied, when asked about the racist attitudes, language and policies that for decades framed the perception and stereotypes of aboriginals living in Winnipeg.

“I hope it’s changing; that the city is more willing to confront that part of its history. In a way, it’s part of reconciliation. To recognize what has been done, to try and communicate to others… you’re shopping in Grant Park (mall) or you’re going to Grant Park High School. This was an area that was previously a community of poor people, many of whom were Métis.

“It makes me look at the streets and houses and buildings somewhat differently when you know what people had experienced there.”

randy.turner@freepress.mb.ca

Randy Turner

Reporter

Randy Turner spent much of his journalistic career on the road. A lot of roads. Dirt roads, snow-packed roads, U.S. interstates and foreign highways. In other words, he got a lot of kilometres on the odometer, if you know what we mean.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Friday, January 29, 2016 1:48 PM CST: Corrects reference to university.

Updated on Friday, January 29, 2016 3:48 PM CST: Replaces photos with better quality versions.

Updated on Sunday, January 31, 2016 1:38 PM CST: Clarifies date of rebellion.