The mother tongue Residential schools almost wiped out the Ojibwe language; Roger Roulette and Patricia Ningewance are working to restore it and its connection to culture

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 29/09/2021 (1531 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

There are millions of people who have written books. How many can say they’ve written dictionaries or thesauruses for a language that was all but lost?

Roger Roulette and Patricia Ningewance can.

Last year, they worked together on an Ojibwe thesaurus. Now, Ningewance, an assistant professor at the University of Manitoba, is working on an Ojibwe dictionary for Manitoba and western Ontario as her research work, along with retired linguist Dr. John Nichols and her own grandson, who is working toward a master’s degree in linguistics at the University of Minnesota. As a skilled speaker and teacher, Roulette is providing input into the Manitoba dialects.

For decades, Ningewance and Roulette have worked to promote the Ojibwe language, drawing on their shared linguistic gifts and upbringings where that language — despite the creep of English — was spoken with a sense of pride and defiance.

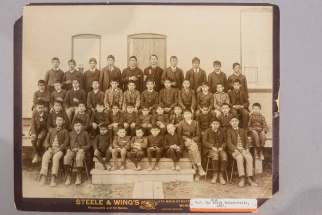

The loss of Indigenous languages was one of the most devastating impacts of the residential school system. Generations of Indigenous children were punished, often violently, for speaking their own language at the schools.

In 2015, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission issued 94 calls to action, including five that focused on Indigenous languages. The ranged from calling on the federal government to acknowledge Indigenous rights include language rights to allowing residential school survivors and their families to reclaim their Indigenous names at no cost.

Roulette grew up in a community outside MacGregor where Ojibwe was the only language. Ningewance, who was taken to residential school on two occasions, had her formative years in Obizhigokaang (Lac Seul First Nation), in northwestern Ontario, where her grandmother, Maaganad, spoke only Ojibwe, refusing to speak English, even though she could do so fluently.

At the age of 20, Ningewance started teaching, and hasn’t stopped for 50 years, while Roulette has been in the language business since the 1980s. Both have written and contributed to several books, while also teaching the language to aspiring speakers and language teachers.

“Everybody spoke Ojibwe at home,” says Ningewance, sitting on a recent morning at the Manitoba Indigenous Cultural Education Centre on Sutherland Avenue. “Right into the city, too,” Roulette says. “We didn’t care about anybody’s judgment. We just, blah, blah, blah, blah, blah.”

“I knew old people who spoke English, but you never heard them utter one word. It was defiance. They’re not going to do it. It’s Ojibwe in the village, and that’s it.”– Roger Roulette

The Free Press spoke with Ningewance and Roulette about language, translation, the future and the destructive impact of colonization on the language today. These are portions of this conversation, edited for length and clarity.

Pat Ningewance: My grandmother spoke English because she was raised with a Hudson’s Bay Company family with a daughter her age, who wanted a playmate. So she was fluent, but she only spoke English when speaking with white people if they spoke to her.

You’ve heard me say this many times, Roger, but I asked her once why she wouldn’t speak English at home if she spoke it so fluently, because I was learning it in school. And she said, ‘We’re not English people.’ And that made such a big impact on me when she said that.

A declaration to preserve Indigenous languages wfpsummary:Our languages are sacred, given to our people by the Creator. We must honour our ancestors who have passed on their knowledge through the language to us, and carry on their work by teaching our families — both as individuals and as a collective — or their words will stop with us and we will break that link.:wfpsummary Our languages are sacred, given to our people by the Creator. We must honour our ancestors who have passed on their knowledge through the language to us, and carry on their work by teaching our families — both as individuals and as a collective — or their words will stop with us and we will break that link. Affirming this sacred responsibility, we, the Grandparents, will uphold our duty and obligations to keeping our languages alive forever. Our languages contain our guiding life principles that are also affirmed in our Sacred Laws, our Treaties and the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. Our sacred cultures contain languages and define who we are as individuals. Our spirituality gives us the strength to overcome the negativity that we face, ensuring that we believe in ourselves as Indigenous peoples. Language connects us with our values and virtues that are instilled within each of us. Considering that: Languages hold knowledge that is carried from one generation to the next; Languages teach us our histories; our Creation stories and our prayers, songs and ceremonies that give us the foundation of our spiritual beliefs on how to live in beautiful and healthy ways; Languages teach us about our land (sky, wind, fire, water and rock) and its many blessings and how to take care of it for future generations; Languages teach us about the importance of our waters, without which we cannot live; Languages teach us about our plants and medicines that heal us; Languages teach us about the Sacred Fire that is our guiding light; Languages teach about the swimmers, the winged ones and the four-legged who are all our relatives and sustain us with food; Languages teach us lessons through our visions and dreams. This connection therefore demands that we must fully accept ourselves by leading good lives and have good relations with all people and all living things as taught by the Creator. We will remain linked to our families, our communities and our Grandparents to ensure that our sacred languages and their teachings will thrive and will live on for future generations. Therefore, we will acknowledge the detrimental impact of the government’s deliberate attempts of stripping our languages and cultures from us, but will no longer be a victim of their oppression but a survivor and will draw from that strength. Therefore, as we make movements to revitalize our languages, we need ongoing moral support, funding, and resources from our families, communities and educational institutions. Therefore, we also know that when we keep our languages alive and teach our children these languages, they will be strong and healthy forever; this is what we strive for in our sacred work. We affirm our gratitude for being connected in a holistic way with all these gifts through language. If we look after the language, it will look after us, too. We declare and affirm our strong commitment to being role models for our current and future generations. We will act with kindness at all times and in all places reflecting and honouring our sacred teachings and responsibilities. The basis of our work will be guided by the Creator and we will be strengthened and blessed in our work. — The Manitoba Aboriginal Languages Strategy Grandparents Council

Roger Roulette: Yeah, I think that’s defiance. I knew old people who spoke English, but you never heard them utter one word. It was defiance. They’re not going to do it. It’s Ojibwe in the village, and that’s it.

PN: I did the same thing with my grandson, Aandeg Muldrew. At first, I didn’t know how to do it. I didn’t teach my son, who is 45 now, and that was the case with everybody in my family around my age. We didn’t teach our children to speak our language because we have this block. I don’t know what it is.

RR: It’s psychological.

PN: Yes, mental, emotional.

FP: It’s not the same, but I grew up with family members who could speak Yiddish, a language that’s been dwindling in usage for decades. And whenever they spoke, I wanted to know what was going on. Now, I’m 26 and I want to learn because I realize how much I wish I understood then.

PN: My grandson (Muldrew) said, like I did, that it’s an act of defiance to speak his language. Because it was suppressed 200 years ago, so for him it was very meaningful to take up the flag to teach it.

RR: There’s a few of them — young second-language speakers — and they’re really great. It’s not like back in the old days, when it felt like it was just me and (Pat) analyzing things. (Laughs).

PN: (When it comes to writing the language and spelling), you have to have an ear. But you can develop that ear over time. It’s easy in French or German orthography, because once you learn it, you can read anything, you might not understand it, but…

RR: One thing people do when they want to impress you is they’ll say something in Russian or German. That isn’t speaking, though. Tell me, “Woher kommst du?” Where are you from? Then, that’s speaking some German. Not (counting to 10) einz, zwei, drei, vier… Then I go, ah, don’t even talk to me.

FP: You both have a gift when it comes to language. When did you realize that, 14 or 15 years old?

PN: I think it clicked much earlier. I was always very verbal, and as a child you’re born to love language. And my grandmother looked after us. She would entertain us, playing word games and telling us riddles.

FP: That’s important. Obviously learning in a classroom setting can be beneficial, but that setting is only one aspect of learning. Life is the other.

PN: Yes. My main job (at the University of Manitoba, where Roulette has also taught) is to teach courses to intermediate and advanced speakers, and I’m very excited because I’m finally trying to do immersion learning.

What I’m doing is writing scripts for them with typical conversations. So they learn them, and then practise them, go off with each other, and commit it to memory. And over and over again they speak until the phrases come out very easily.

FP: Kind of like acting.

PN: Yes. This week they’ve learned their lines from 20 little scripts, and we’re going to practise intonation. I’m not happy with their pronunciation, so we’ll work on that, and soon they’ll sound very Ojibwe, and that’s very exciting to me.

FP: So what’s in the scripts?

PN: Only expressions we use. I don’t want a translated language, because then we’re speaking and translating English right?… You know what annoys me? Some teachers will teach “How are you?’ and if I said (says a direct translation in Ojibwe) to Roger, that’s like me asking, “What’s wrong with you?” It’s implying that something is wrong.

FP: So what would you say?

RR: Well, the thing about it is that when you translate English sentiments, like “What is your name?” Well, that’s rude. When I was growing up, nobody asked that. They say, “Nice weather. Where are you from?” And they tell you their clan.

PN: And then the name.

RR: When Pat and I first met, she had a little bear, and I knew right away. Same clan.

• • •

FP: This is broad, but what are you trying to accomplish through your work? Is it to correct misconceptions? Clarify the realities? Is there even one goal?

PN: To bring the language back, that’s my goal. I want to create a new generation of speakers. I created one with my grandson, and he’s assisting others to do the same.

RR: To trailblaze, to do the hard work, is something we can offer to the younger people.

FP: When you started this work, around 1988, you were much younger. Now, some people might look to you as the ones who know the most about the language, or elders, even though you probably don’t see yourself that way.

RR: Firstly, I don’t like the word “elder.” It’s an English word that imposes connotations on what people are supposed to be when they’re “elders,” even though they’re all unique, with different personalities and specialities. That word, to me, goes back to a more Christian religious basis. So I don’t use that word. I say old people. Growing up, that’s what we called them.

FP: So you’re old people now.

RR: (Laughing) Yes, we are, relatively.

PN: But I don’t like being called an elder either. You’ll hardly find anybody who would refer to themselves like that. I don’t feel that I am. I still have so much to learn.

FP: Roger, when you grew up it was in a unilingual community. Was it rare to have a place like that, where you could maintain the language and avoid the intrusion of English?

RR: We didn’t think of it as rare, because we did it. Maybe it was on one hand, because they refused to speak English. And the town was right there. You could see it. And here we are in another world. I think their goal was to pass on not only the language but the culture.

“When the Europeans came here, they should have learned our languages, not the other way around.”– Patricia Ningewance

FP: And that’s what you both do now, in a different way, like with the Northern Ojibwe dictionary, the upcoming Manitoba and western Ontario dictionary and recent thesaurus. What was making the thesaurus like?

RR: It was a real brain drain. Even though we’re adept. It involved a lot of research and interviews.

PN: We would look at one word, let’s say, “sleep.” Well there are many ways to sleep. Sleep well, sleep on this side, poo while you’re sleeping, sleep poorly. We just sat in my backyard, going back and forth.

Interestingly, when it came to hugging, we couldn’t come up with many words for it, but for killing and fighting, there were many. It tells us something about our culture and history. Fighting was very important to stay alive against enemy strife. We just didn’t go around hugging too much.

RR: There are words that have no English translation either.

FP: Creating a dictionary is important, but it isn’t easy I’d assume. What’s the biggest challenge?

RR: You have the root word, and the derivatives. So what do you include in there? If you include everything, you can have a book 2,000 pages thick. Ojibwe has a million words. How do you wrestle with that?

FP: So you feel some pressure?

RR: Well, I like pressure, so it’s a lot of fun.

“I remember this young fella. He said he didn’t speak that well, but he was talking about Anishinaabe philosophy. And I was thinking, buddy, you knew how to speak. Be proud. He just spoke really well. I liked it.”– Roger Roulette

FP: Are you ever concerned that no matter how much time and effort you put in, it won’t be enough to account for the tremendous loss of language and culture that’s happened through colonization? Has that entered your mind?

PN: It does, yes, but I don’t let it control me. There will be people so colonized that they cling to English. It’s familiar. It gives a sense of safety. People don’t try to learn new languages, even ancestral ones, because of fear. That’s the depth of the colonization. You want to cling to English even though you’re not an Englishman.

RR: It’s ubiquitous. You can become brainwashed.

PN: Now that’s what we have to deal with as teachers. To move them away from that.

RR: I think, I think the foundation is being laid, like at language camps, and then people who are second-language speakers that actually can speak it, you know? So we see it, we just have to push it further. I remember this young fella. He said he didn’t speak that well, but he was talking about Anishinaabe philosophy. And I was thinking, buddy, you knew how to speak. Be proud. He just spoke really well. I liked it.

• • •

FP: One thing we talk about often is imagining a better future in Canada. I think that’s a lot of what the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation is about. What’s another attainable goal for this work, and how does that fit into a better future?

PN: I would like to see a mandatory language course in university. I remember one nurse a long time ago was shocked to learn Ojibwe had grammar. Can you imagine that?

RR: I think a B.Ed. should have a mandatory course in a native language. How are teachers going to teach about the language unless they learn about it?

PN: I have this vision of a time when our language will be strong. Maybe just within a community. Maybe 200 people, in the far future, so they would be the beacons.

RR: It would be really nice to have a village where the language is spoken there and we can learn things you’re not able to teach in a classroom. How do you prepare duck? How do you prepare rabbit? How do you skin a deer or moose? That is, for us, survival. I’m sure she saw it. I saw it.

That’s also part of language survival. It encompasses so many things.

FP: I know you have to go work on the dictionary, so is there anything you want to add?

PN: I would say that language can be a mess, and Roger and I are two people trying to make sense of that mess. Our language has been deemed second-class from Day 1.

When the Europeans came here, they should have learned our languages, not the other way around.

ben.waldman@freepress.mb.ca

Ben Waldman covers a little bit of everything for the Free Press.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.