A labour of love

Roger Roulette spent a lifetime dedicated to understanding, analyzing and preserving his native Ojibwe language

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 10/12/2022 (1181 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

It’s hard for Pat Ningewance to guess how many times it’s happened, that she’ll be working on a translation and find herself stuck. It’s never easy to translate between tongues, especially two as different as English and Ojibwe; so even Ningewance, a renowned University of Manitoba professor and translator, sometimes comes across a term that leaves her stumped.

In those moments, there’s always been just one person Ningewance wanted to call: her close friend, Roger Roulette.

There are many people who speak Anishinaabemowin, but few who understood it as deeply as he did. Roulette, it seemed to his friends, knew almost everything about the language, from regional differences to the cultural information encoded in the words themselves. When it came to analyzing Ojibwe grammar, he could go toe-to-toe with any trained linguist.

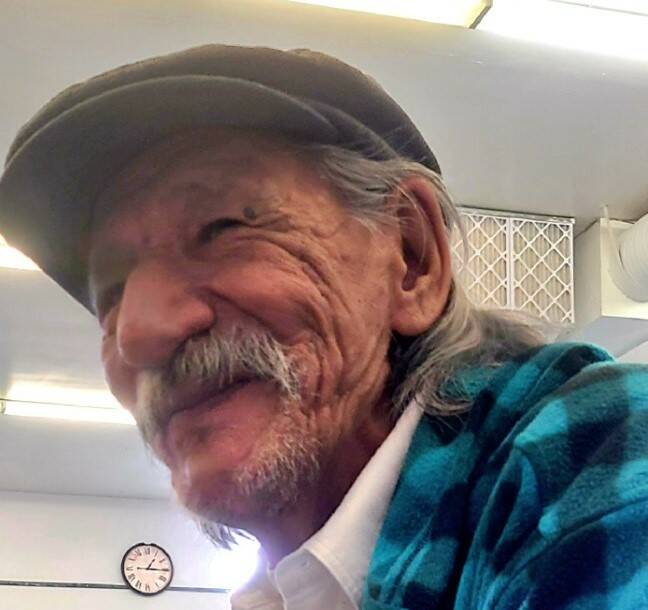

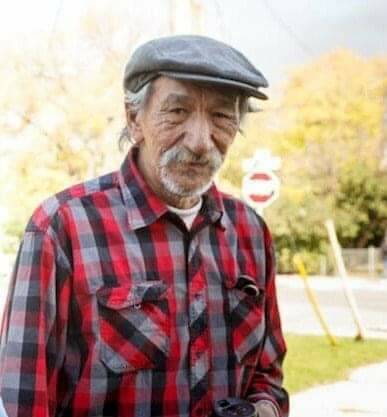

MIKE DEAL / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS FILES

Friends and language activists Roger Roulette (left) and Pat Ningewance at the Manitoba Indigenous Cultural Education Centre in 2021. Roulette died in November at the age of 64.

So together, Ningewance and Roulette made a powerful team. They’d spend hours diving into the language’s vocabulary and structure, comparing notes, puzzling out terms. These discussions weren’t dryly academic: Ojibwe is a vivid language, rich in description, brimming with humour. With his quick wit, Roulette was funny in any tongue, but especially his first one.

“We spent a lot of time together, and we would just talk in our language, and laugh, have a great time,” Ningewance says.

Now, she and his many friends must try to imagine how that work will go on without him. Because when Roulette died on Nov. 3, just two weeks after being diagnosed with cancer, the 64 year old left behind a vast legacy of service to his Ojibwe language and culture, but also a hole in the close-knit community that may never be filled.

“We’re all just trying to pick up the pieces,” says Manitoba Museum cultural anthropology curator Maureen Matthews, who first met Roulette when she was a CBC journalist and became a lifelong friend. “All of us leaned on him and his competence and understanding, and his generosity to do that work.”

Roulette’s skill with the language grew from the root. A member of Sandy Bay First Nation, he grew up in MacGregor, part of a big family that spoke Anishinaabemowin at home and held their culture close. He was a shy child, he later told his friends, more into reading than sports, and he spent his childhood listening to relatives socializing in Ojibwe.

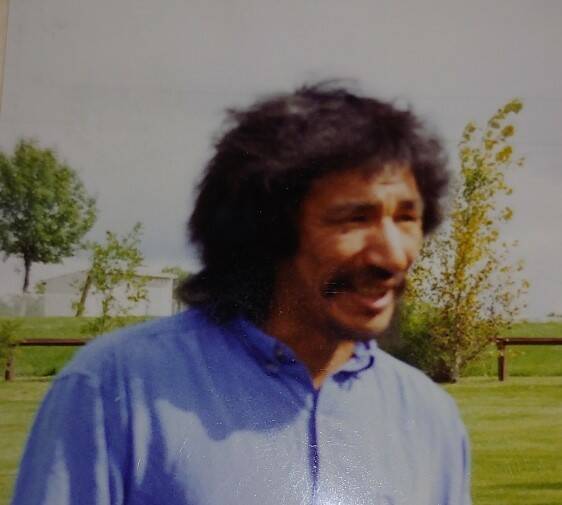

SUPPLIED

Roulette believed that accurate information about Ojibwe culture and traditions was held in the language.

That experience, Ningewance says, was a gift, one that Roulette would go on to share with the world.

“He grew up in the language, he was very lucky to do so,” she says. “To hear older people speak, you absorb a higher level of language and he spoke that higher level. I don’t know anybody else right now, except for people who are older than me, that speak that level. Nobody in their 60s like he was can speak that level of Ojibwe.”

Early on, Roulette showed a knack for understanding language. He studied German in school, and after moving to Winnipeg with his family as a teen, he gravitated towards people and organizations working with Ojibwe; by the mid-1980s he’d begun teaching night classes at what was then the Manitoba Association for Native Languages, where he met Ningewance.

The two became fast friends. Roulette had the ability with the language, but not the formal training, so Ningewance taught him how to teach, which he picked up “like a duck to water,” she says. He learned Ojibwe’s syllabic writing system and also immersed himself in understanding the technical aspects of linguistics that gave further weight to his translations.

As a translator, friends say, Roulette was gifted. No task was too challenging. One day he’d be working on dense documents about treaty law; the next, he’d happily accept a request to craft an Anishinaabemowin version of the Sonny & Cher classic I Got You Babe. No matter what he was doing, he would complete these projects at a remarkable pace.

SUPPLIED

Roulette studied German in school and gravitated towards organizations working with Ojibwe.

“He made it seem easy,” Matthews says. “He could do half an hour of transcription and translation in a couple of days. It would take most people a month. He could type 30 words a minute in syllabics. He was just amazing. And the thing about Roger was that he did it for love of those people. You could never pay him for the work he did.”

Indeed, for most of his life Roulette never took full-time employment. Mostly, he was too busy with his constant stream of projects. In the 1990s he started working closely with Matthews, travelling to remote First Nations to interview knowledge-keepers; that collaboration would blossom into decades of work and more than 500 hours of preserved oral histories.

“He always tried to find time to do the really important work that he knew other people couldn’t do,” Matthews says.

With Ningewance, he worked on a thesaurus, and was most recently collaborating on a dictionary. He also taught Ojibwe at the University of Manitoba to glowing student reviews — “Lots of fun and laughter in his class,” one student wrote online — and co-authored several books, including the textbook Gindinwewin: Your Language, Level One.

Part of what drove Roulette in this work, friends say, was his firm belief that accurate information about Ojibwe culture and traditions was held in the language. He had strong opinions about what terms were authentic, and was openly critical of the adoption of translations that he considered to be a whitewashing or a stereotype of pan-Indigenous knowledge.

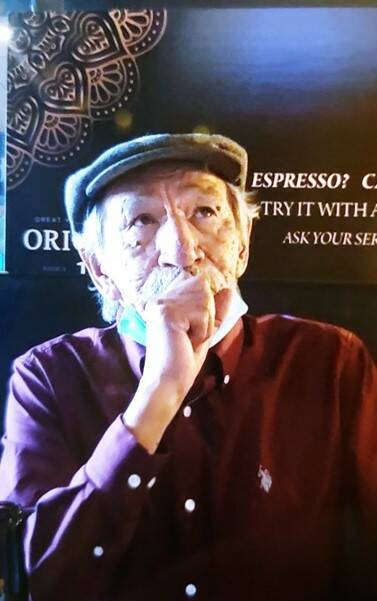

SUPPLIED

Roulette taught Ojibwe at the University of Manitoba to glowing student reviews.

So terms like “Mother Earth,” that would “send him through the roof,” Matthews says; it wasn’t a proper translation of the Anishinaabemowin term. Once, longtime friend Carol Beaulieu recalls, Roulette did a seminar about Anishinaabe ways, in which he showed how to understand a concept by exploring the Ojibwe term first, before translating to English.

Roulette was proud of this work, but he always acknowledged the long line of people from whence it came.

“He always made sure that you knew that this wasn’t his idea, it wasn’t his information,” Beaulieu says. “It was information that was gathered from speaking to different people, different older people through the years.”

In and around all of this, he still found time to savour life. Roulette loved to walk, and often strolled from his north Winnipeg home to the Indigenous Languages of Manitoba office in Point Douglas. He had no children of his own, but loved taking care of some of his grandnieces and grandnephews, with whom he was very close.

Most of all, he just enjoyed every second of what he was doing — and perhaps that’s what inspired him, most of all.

SUPPLIED

Roulette believed accurate information about Ojibwe culture and traditions was held in the language.

“To work in the language is fun,” Ningewance says. “It wasn’t just, ‘I gotta do this because it’s very important.’ We know it’s important, but it’s also very much fun.”

One way or another, that work will go on. Several of Roulette’s friends are planning to gather and preserve his files, making them available for future scholars and learners. The American Philosophical Society recently digitized its trove of translated oral histories that Matthews and Roulette had gathered, and made them available on its website.

Meanwhile, his voice will not soon be forgotten. Nearly every day, his friends say, they come across something that reminds them of Roulette, or something they wish they could share with him. A word that would have benefited from his thoughtful translation, something he would have found funny or even something that would have set him off on a rant.

”I recently looked at a book where the person mixed up the animate and the inanimate (Ojibwe grammar) word,” Beaulieu says, and chuckles. “I just started laughing, because I knew Roger would be like, ‘Oh my God, what are these people doing?’”

melissa.martin@freepress.mb.ca

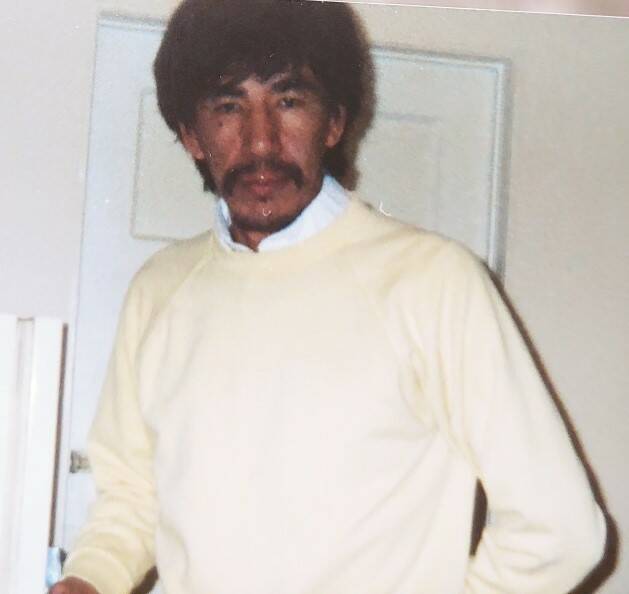

Mike Deal / Winnipeg Free Press files

Roulette loved taking care of some of his grandnieces and grandnephews, with whom he was very close.

Melissa Martin

Reporter-at-large

Melissa Martin reports and opines for the Winnipeg Free Press.

Every piece of reporting Melissa produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.