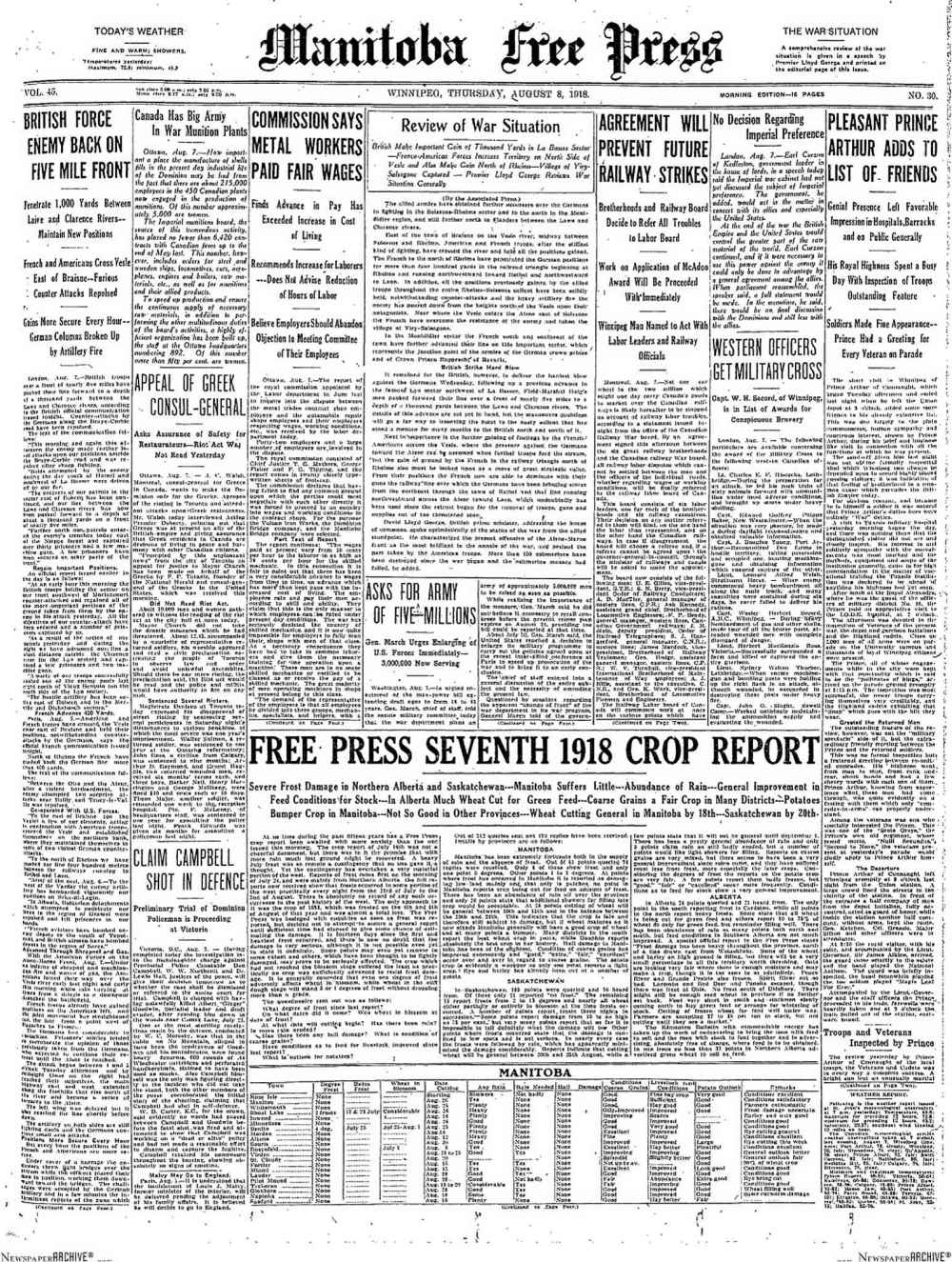

Ministering amid the mayhem Manitoba chaplain's 100-year-old diary entries from France offer a glimpse of the blood-stained beginning of the end

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 10/08/2018 (2677 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

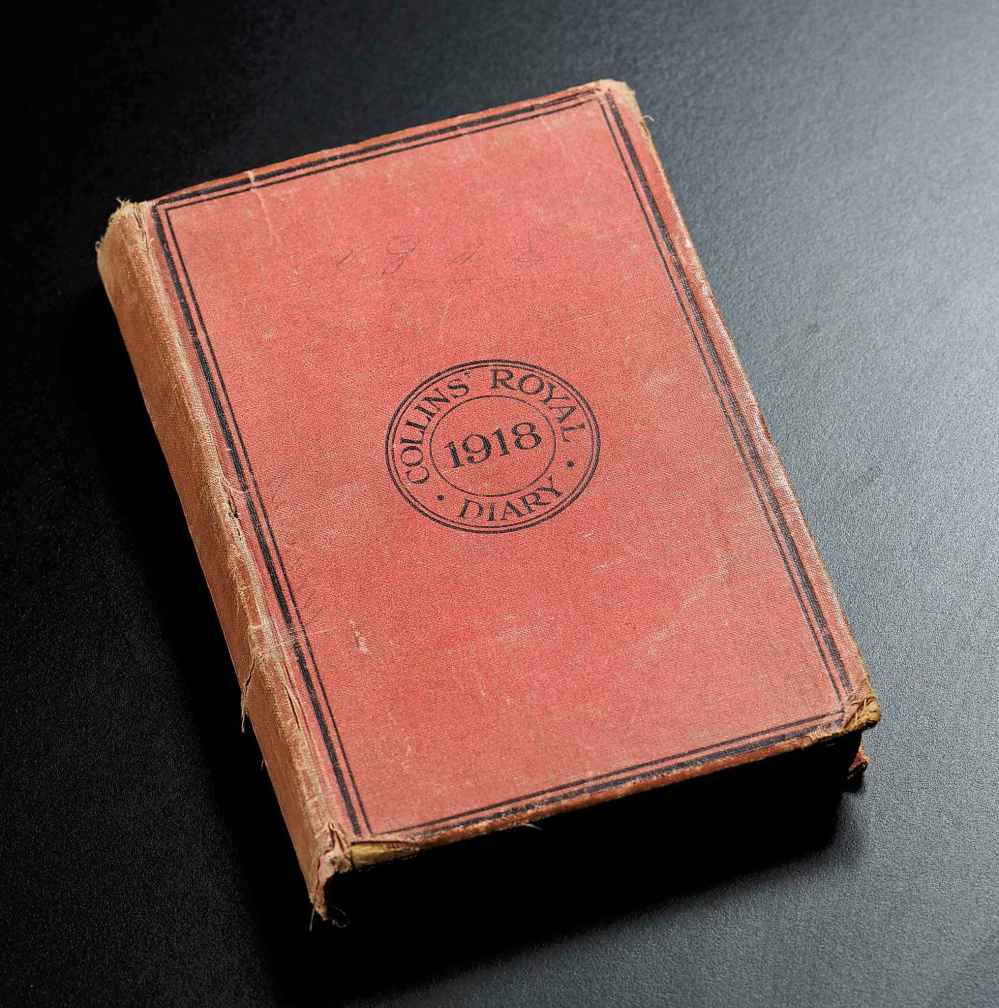

By August 1918, the padre’s flag had covered hundreds of Canadian soldiers’ bodies as he put them into their shell-strewn graves and said the final prayers.

With 100 more days of war to come, the flag would cover hundreds more.

Today, the worn, muddy and stained Union Jack can be seen in Winnipeg’s 1st Presbyterian Church. But back then, it belonged to Capt. James Whillans, a Presbyterian minister who was the chaplain of the 8th Canadian Battalion in 1917-18.

As a front-line chaplain in the First World War, Whillans faced the same daily dangers as an ordinary soldier. Snipers, machine-gun bullets, artillery shells, trench mortars and poison gas showed no respect to a man of the cloth. He was devoted to the men and, according to Whillans’ family lore, he had to be urged to speed up interment services when shells began to land too close for comfort.

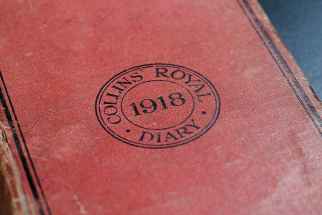

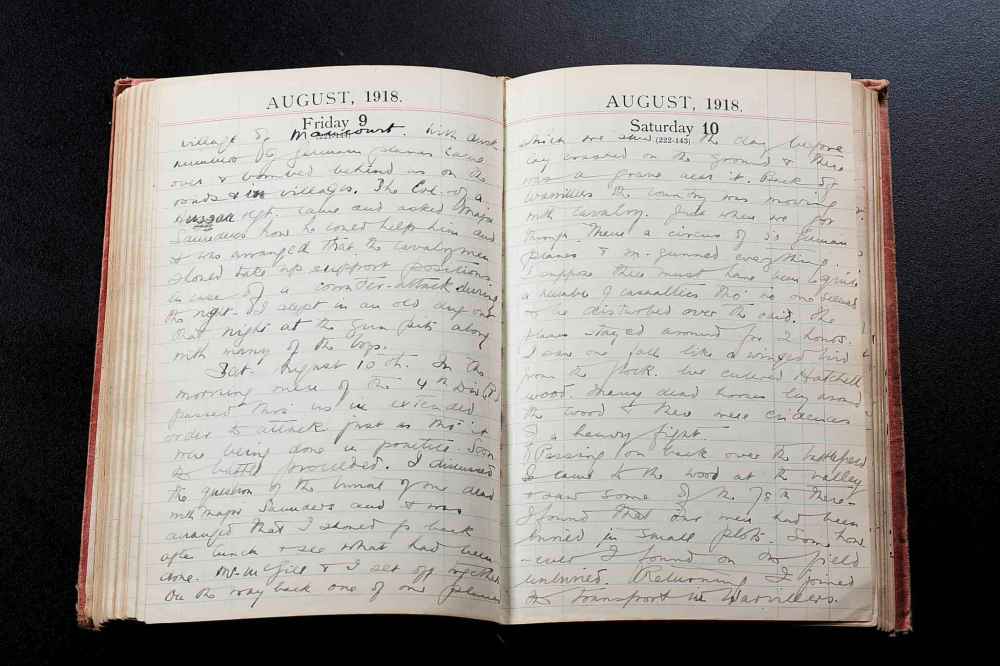

“I remember when burying the officers, during the last prayer I heard a rat-tat-tat in the sky…,” Whillans wrote in his 1918 war diary.

● ● ●

Five months earlier marked the beginning of the end for the German forces. In March 1918, they launched a desperate last-ditch spring offensive in the hopes of breaking the Allied lines to force a peace deal before millions of American soldiers arrived on the Western Front.

The offensive failed and the Allied High Command decided it was time to unleash a massive counter-offensive on a weakened and demoralized enemy. They chose the ancient French city of Amiens as the point of the attack.

The Canadian Corps, the vaunted shock troops of the British Empire, would spearhead the assault. The Canadians left their lines, about 10 kilometres from Vimy Ridge, on Aug. 3, 1918, and arrived at Amiens two days later.

The Canadian Battalion’s daily War Diary reported the men were “in fine fettle” and “the Battalion was never in better shape.” On Aug. 7, the men moved up into position and awaited the start of the battle. In their ranks was Capt. Whillans.

The Battle of Amiens was a modern combined-arms battle. Hundreds of tanks and thousands of aircraft worked together with artillery and infantry to overpower the enemy. After months of trench warfare where success was often measured in feet and inches, the Canadians drove the Germans back an unprecedented 13 kilometres. On Aug. 9, they advanced another six kilometres. However, the German defences stiffened, the Allied armies lost momentum and the offensive ended on Aug. 11.

The Canadians suffered 4,000 casualties, with 1,016 killed in the battle. The 8th Battalion (90th Winnipeg Rifles) fought as fiercely as any other battalion. When they left the battlefield on Aug. 20, the 8th had taken 440 casualties with 107 dead.

Two men from the battalion, Winnipeg’s Frederick Coppins and Oak River’s Alexander Brereton, each were awarded a Victoria Cross on Aug. 9.

Whillans’ war diary transports readers back in time to the 100-year-old battlefield as we see him minister to soldiers’ spiritual needs, as well as their psychological and physical needs.

Aug. 8, 1918:

“After a hurried breakfast… I found myself on the road and pressed forward. There were many men and vehicles on the road and all were bent on getting to some place where duty called them for the day. I found a Y.M. (YMCA) and filled my haversack with chocolate and cigarettes. This was a fortunate thing as for many days during the advance of fighting I was in a position of being able to supply each man who desired one or the other. Cigarettes had been almost unobtainable for the battle and were highly prized… never was a battle fought with so few cigarettes for the men…

“The battle had started and proceeded successfully. The enemy was taken by surprise at 4:20 a.m. The men moved forward at the attack and went on after dispatching his first line of defence. The tanks did splendid work and moved forward effectively against all enemy opposition…

“The morning was misty, and the sun shone through the mist and it seemed as though the day would be clear, but the mist settled more thickly and obscured the sun entirely. The sun came out, eventually, and I thought, ‘It is the sun of Amiens, the sun of victory’…

“I went south down the side of the valley, which was filled with cavalry. Shells were falling. Up one valley I saw horses and men hit as I passed and further up came on an aid post belonging to a cavalry unit. German planes had been over that morning and spotted them, so that they had been heavily shelled and had many casualties. Dead horses were lying around and men on stretchers were lying at the aid post. I spent a considerable time here with a dying man who had Y Somerset on his shoulder and who did not want me to leave him. Meanwhile, shelling continued and m.g. (machine gun) bullets swept the valley from the south…

“Tanks and (artillery) batteries came from the west. In a few minutes, the latter were in action. Further up the valley at the north end of the wood things were very hot. I stood a few minutes before I realized this, when I saw several shells fall close at hand, I hastily concluded that the spot was as unhealthy as any place. M.g. bullets were falling on the ground and singing through the air…”

Whillans was 37 and married when he enlisted in the Chaplains Corps in 1915. At the time, he was serving as minister of the Presbyterian Church in Balmoral. He was assigned to the 8th Battalion when he went to England.

His rank was honorary captain, based on his professional status, and would have same privileges of that rank. He would have worn his clerical collar and chaplain insignia, but other than that, he would be dressed like an ordinary soldier or officer and be covered in mud.

He would not have done any grunt work in the trenches, but would have assisted stretcher bearers, helped in hospitals and held services. Military chaplains often set up coffee and tea canteens and wrote letters for illiterate soldiers, of which there were many.

Whillans, who was older than most Canadian soldiers, was literate, reflective and had a flair for writing. He describes coming across a wounded German machine-gunner during the fighting on Aug. 8:

“On both sides of the valley the ground slopes gently. There are woods and open fields. At the edge of one wood commanding an open space, we found a m.g. and a dead gunner. Near there behind a little mound was an m.g. and a wounded German who had bound up his thigh wound. He lay in a little hollow beside a large number of empty cartridges that told of his own story. Sudden anger flashed in my eyes as I saw it all, and as he looked up he saw that and saw, too, that I was an officer. His eyes passed from mine quickly and he glanced back as tho he feared what might happen. He evidently expected death and his eyes grew less startled as I turned and passed on…

“The 8th Battalion took very few casualties during the first day of the battle and the War Diary stated that “the Battalion had reached its objective fit and ready for any new orders with only three casualties. That evening the commanding officer attended a brigade meeting and was told that the brigade would be advancing the next afternoon.”

Aug. 9, 1918:

“The East Rim of the valley and the wood, as I afterward learned, was the front line and from there the boys began an attack at 1:00 p.m.… an odd shell whizzed close over my head and struck the ground… Meanwhile, the battle in front had proceeded.

“The tanks it seems were late in coming and the attacks started without them. The OC (officer commanding) Major Raddall went forward to see for himself what the situation was, walking right into an exposed position he was shot in the breast and died almost instantly.

“The wood was shelled heavily, and we had many casualties. In front there was an old system of trenches the Germans had manned with machine guns, many reinforcements and, I afterwards understood, had been brought up by motor lorries overnight…

“Our men advanced in the face of the fire and overwhelmed the opposition… Over a railway in the valley is a wood which we have named Hatchet Wood. There the enemy made a stand with m.gs. It was here that one, if not both VCs earned by the battalion in the battle, was won. Corp. Coppins and Pte. Brereton were the recipients and their acts were much alike. They attacked m.g. nests and cleaned them out, killing the gunners or making them prisoners.

“Hatchet Wood, as I afterwards saw, was filled with German men, material, wagons huts, dumps, etc. It had been a small camp. It lay right in the path of our advance and but for the spirit and dash of our men would have held us up… The advance met that day was around 4 miles. We understood that on the first day the advance of 8 miles was the greatest distance that had been covered by any army in a single day on the Western Front.

“Meanwhile, I was at the dressing station where the wounded were coming in. All afternoon we were busy. There were many stretcher cases and German prisoners were helping our stretcher bearers. For some time, there was a congestion of wounded as the ambulances being slow in arriving. Some patients were far gone and died there. Captain Campbell our M.O. (Medical Officer) worked hard as did everyone and the wounded were attended to rapidly. Several of the officers were brought in and we got word from one of the men that the OC had been killed. As usual, many wild stories were told along about the battalion being wiped out.

“I took messages from the men, gave them cigarettes and chocolate and helped to dress them. The place where we are operating had been a German C.C.S. (Casualty Clearing Station) and we used the tents which were still standing. The place we knew afterwards as Hospital Valley.

“On the morning of Aug. 9, the battalion had nearly 850 men ready for action. By evening, a meeting of the remaining battalion officers was called and, as the War Diary notes, “before the officers retired to rest the battalion was once more re-organized and ready for action 400 strong.”

Losses on this scale were not uncommon in Canadian infantry battalions in the First World War.

During the Great War, the 8th Battalion had an 84 per cent casualty rate with 27 per cent killed: 5,939 men served, 4,996 were casualties of which 1,584 died.

Aug. 12 to 20, 1918:

Whillans would not have carried a weapon, despite facing the same dangers as regular soldiers. He would have worn clerical robes in regular services, but likely only his stole — a band of coloured cloth — for interments. There was no regulation chaplain’s kit, but he would have carried in his haversack his bible, vestments, a cross and items for communion.

Signed Stanley

While fighting in the First World War, Cpl. Stanley Evan Bowen also fought to keep the flame alive between him and his sweetheart in Winnipeg by writing more than 150 letters.

The Free Press has been retracing his steps to the day based on those letters with a twitter account @SignedStaney.

While fighting in the First World War, Cpl. Stanley Evan Bowen also fought to keep the flame alive between him and his sweetheart in Winnipeg by writing more than 150 letters.

The Free Press has been retracing his steps to the day based on those letters with a twitter account @SignedStaney.

The battlefield service would depend on the soldier’s faith — the vast majority of soldiers in non-Quebec battalions were Anglican or Presbyterian — but likely include the familiar words of sacrament — “ashes to ashes, dust to dust. In the hope of resurrection unto eternal life…”

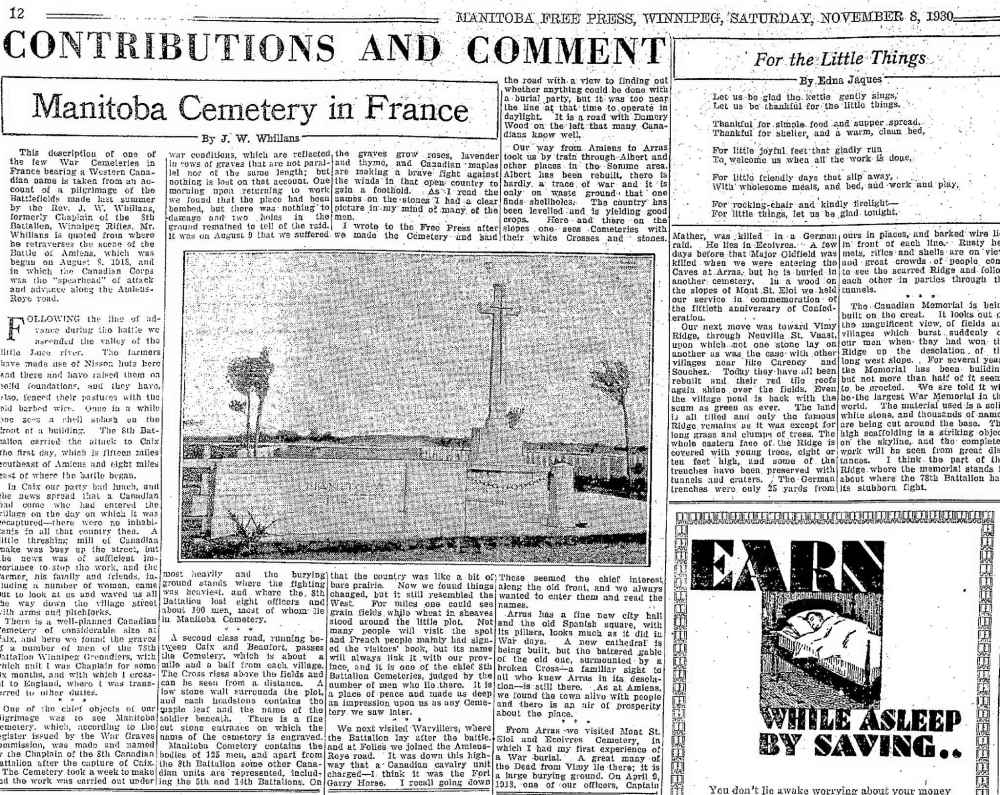

Whillans, who was born in Scotland but came to Canada in 1910, writes that as a chaplain his duty was to bury the dead, report the soldier’s name and place of the burial. There was a battalion burial officer who was responsible for gathering the bodies and creating a proper permanent cemetery. However, the officer had other responsibilities and was not able to do so. Whillans organized men to gather the bodies, which still lay on the battlefield or were buried in unmarked graves and build a cemetery.

He knew that if he did not do this, the bodies would be lost, would not have a Christian burial or a known grave. They would join the thousands of other Canadian men who were, as the official Commonwealth War Graves Commission tombstone reads, “A Canadian Soldier Known unto God.”

“(I) requested 20 men and a G.S. (General Service) wagon to remove the hastily buried bodies to a central cemetery, which would be permanent. Next day we set to work, the request having been granted and over 60 bodies were removed. The plot where the OC (officer commanding) and other officers lay was made the central cemetery.

“For several days I rode backward and forward over the battlefield locating scattered graves and unburied bodies and having them taken to the main burial place. The weather was very warm. The cemetery I had named ‘Manitoba Military Cemetery’. Nearly 70-8th Battn. men are buried there.

“I remember when burying the officers during the last prayer I heard a rat-tat-tat in the sky, and when I opened my eyes after the benediction the first thing I saw was one of our balloons (artillery observation balloon) going down in flames and a German plane rushing away.

“I knew all the men who were killed and saw most of their bodies afterward before burial. The cemetery lies in a wide open plain like Manitoba. During the Battle of Amiens our casualties were 440 all-ranks and 8 officers killed (107 men killed).”

Whillans’ flag covered the bodies of the men who died at Amiens. It also covered 700 other 8th Battalion men. After the war, Whillans served in various churches in Manitoba and Saskatchewan. He made a point of visiting relatives of men from the battalion who had been killed.

Ian Stewart is curator of the Royal Winnipeg Rifles Museum and editor of Holding Their Bit: Remembering the 8th Canadian Battalion (90th Winnipeg Rifles), The Little Black Devils.