Valour overseas, scandal at home

The brutality of front-line fighting became clear to Winnipeg in 1915

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 01/08/2015 (3877 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

For Winnipeggers, it became clear midway through 1915 the cost would be high and the war would not end soon. The reaction of the majority of people was patriotic and courageous and most accepted great sacrifices would have to be made.

On the home front, people supported the war effort by raising money and volunteering for agencies such as the Red Cross and the Patriotic Fund, established to support the families of soldiers.

Meanwhile, the most serious political scandal in Manitoba history was unfolding, followed by an election that changed the political landscape dramatically.

Raising the First Canadian Division had been relatively easy. About 30,000 men volunteered and were ready to leave for Europe two months after the outbreak of war on July 28, 1914. During 1915, two more divisions were recruited and sent overseas, but the early enthusiasm had begun to wane and it was harder to convince young men to volunteer.

Canadians saw action for the first time. In mid-February, the three infantry brigades of the First Canadian Division had crossed the English Channel to France after an uncomfortable winter in the rain and mud of Salisbury Plain. The troops and their officers spent time in trenches about 16 kilometres south of Ypres, Belgium, paired with British units. Everyone from the generals down to the privates learned something about trench warfare.

On March 5, the Canadians moved to the Ypres area. The old medieval city was still largely intact and inhabited. It would be an unrecognizable moonscape, smashed to pieces by German shelling, by war’s end.

The Canadians took over a section of front-line trenches on April 14, with the French 45th Division on their left and the British 28th Division on their right. They were about six kilometres northeast of Ypres, defending a short section of the so-called Ypres Salient, a bulge in the allied line jutting into German-held territory that had been — and would continue to be — fought over throughout the war. The area of the Ypres Salient is home to numerous Commonwealth cemeteries and many thousands of Canadians lie in them or in unmarked graves beneath the farmers’ fields that cover the battlefield sites.

For the Canadians, the real war commenced on the afternoon of April 22, when the German army released the first large-scale chlorine gas attack in history. The densest part of the gas cloud hit the French troops to the left of the Canadians and hundreds of the mainly Algerian soldiers died horrible deaths. They were not equipped with gas masks that would soon make the gas attacks less deadly. The French troops, terrified by this new weapon, broke and ran, leaving a 3.5-km wide gap in the front line. The Canadians now had to defend their section as well as move troops to attempt to close the gap and prevent the Germans from circling behind them and cutting them off.

A century later, the Menin Gate in Ypres, Belgium, displays the names of 54,000 men of the British and Commonwealth armies who died at Ypres during the First World War and have no known grave. Even now, soldiers’ bodies are occasionally found by farmers and given proper burials. (Yves Logghe / The Associated Press)

A century later, the Menin Gate in Ypres, Belgium, displays the names of 54,000 men of the British and Commonwealth armies who died at Ypres during the First World War and have no known grave. Even now, soldiers’ bodies are occasionally found by farmers and given proper burials. (Yves Logghe / The Associated Press)

The 8th Battalion, made up mostly of members of the Winnipeg Rifles regiment, which was nicknamed the Little Black Devils, was one of the four Canadian battalions in the front line that day. They, with British troops and the remnants of the French units, fought hard to hold both the front line and a line along the Poelcappelle Road that had divided the French and Canadian zones. The Germans moved forward through the gap and, at that point in the battle, there was every chance they would push past Ypres and advance the approximately 40 km to the English Channel.

One of the reasons they did not was the stubborn resistance they encountered from the Canadian troops. Over the next five days, the Canadians and their French and British comrades struggled to slow the German advance, close the gap in the allied line and launch a number of counterattacks.

While the enemy did manage to push the perimeter of the salient back two kilometres, they were ultimately prevented from breaking through to Ypres and the country beyond. In the crucial first three days of the battle, before substantial French and British reinforcements arrived, the Canadians made an outstanding contribution. Units such as the 10th, 16th and 8th Battalions distinguished themselves. On the night of April 22-23, the 10th and 16th Battalions, both units with Winnipeg troops, carried out a counterattack that captured Kitchener’s Wood and held it for several hours before they were forced to withdraw.

The two units suffered heavy casualties during this battle. The 8th Battalion was one of two units in the path of a second gas attack on April 24 and suffered casualties from the chlorine gas. The Little Black Devils held their part of the trench in spite of having many men killed and disabled by the gas. They kept firing into the advancing Germans during their initial attack until it faltered and the enemy withdrew. The Battalion lost 22 officers and 550 other ranks — two-thirds of their numbers were killed or wounded in the fighting at Ypres.

It was on April 24 that Sargent Major Frederick William Hall of the 8th Battalion was killed while rescuing a wounded comrade who had been lying in no-man’s land. Hall was awarded the Victoria Cross for his bravery, one of three men from Valour Road in Winnipeg to win the medal.

The overall Canadian casualties during the battle totalled 208 officers and 5,828 other ranks, about one-third of the Canadian force. The War Office, in a communiqué, stated that while the Canadians had suffered heavy casualties “their gallantry and determination undoubtedly saved the situation.”

Many commented on their bravery and MP Max Aitken, head of the Canadian War Records Office in London made sure their exploits were covered in the press. In 1916, he published Canada in Flanders, a multi-volume official history of the Canadian Corps that chronicled their successes. Ypres marked the origin of the Canadian reputation as being tough and determined fighters.

The much-depleted Canadian battalions suffered more casualties in two more battles in 1915 — at Festubert in May and Givenchy in June — after which they were able to rebuild and rest.

Back in Winnipeg, news of the losses suffered in the battle at Ypres was slow in arriving. It was not until July 26 that the papers had news of the casualties.

Unofficial reports of heavy losses had begun to circulate in the city the previous day and people, frantic with worry, phoned the newspaper offices. The Free Press reported that their offices had been “besieged” with calls and “anxious relatives who came direct to the newsroom in a desire to hear the worst. There were many sleepless ones in Winnipeg last night. The war has struck home.”

Front line trenches, Ypres, Belgium. The Battle of Ypres in the First World War was a baptism of fire for a fledgling force of Canadian soldiers. (George Metcalf Archival Collection Canadian War Museum)

Front line trenches, Ypres, Belgium. The Battle of Ypres in the First World War was a baptism of fire for a fledgling force of Canadian soldiers. (George Metcalf Archival Collection Canadian War Museum)

The battlefield chaos made it very hard for officials to find out who was wounded or dead. The Militia Department in Ottawa said it would be a few days before the casualty lists would be complete, but even today, 100 years later, the Menin Gate in Ypres displays the names of 54,000 men of the British and Commonwealth armies who died at Ypres during the four years of war and have no known grave. Even now, soldiers’ bodies are occasionally found by farmers and given proper burials.

The names of men killed or wounded at Ypres in 1915 appeared in the Winnipeg newspapers each day, sometimes accompanied by photos. Men of the 8th Battalion who died included, among many others, Pte. Oscar Lebean, a clerk at the Vivian Hotel, Pte.William Irvine, an Eaton’s store clerk, Pte. John Gloag, a teamster, and Pte. Douglas Wilson, a shipper at Dominion Lumber.

Lt. G.F. Andrews, also of the 8th, did not survive. He was 22 and had worked with his father selling real estate. Lt. G.A. Coldwell, 22, was also killed. He was the son of George Coldwell, a cabinet minister in the Roblin Government. Pte. Stanley Freeman was listed as suffering from the effects of gas. He worked for the Canadian Northern Railway and he was a well-known and popular football player in the city. The lists went on and on, recording the damage the war had already done, at a time when there were still three-and-a-half years to go before its end.

On April 27, the Governor General, the Duke of Connaught, announced a memorial service would be held in Ottawa’s Lansdowne Park two days later. Winnipeg Mayor Richard Waugh suggested local services should be held at the same time. The service took place on the former site of the Happyland amusement park on Portage Avenue.

Thousands of troops stationed in the city and an equal number of civilians attended the simple service. Clergy from several different churches, including both the Anglican and Roman Catholic Archbishops, officiated.

The main speaker, Dr. G.B. Wilson of Augustine Presbyterian Church, spoke of the noble sacrifice made at Ypres by Canada’s citizen soldiers who were not interested in conquest but in restoring peace. He said the struggle against Canada’s rugged environment had prepared the men for the adversity of war. These were themes that would be repeated again and again at such events during the war.

By the summer of 1915, there were 10,000 men training at Camp Sewell, west of Carberry, which was soon to be renamed Camp Hughes.

By the summer of 1915, there were 10,000 men training at Camp Sewell, west of Carberry, which was soon to be renamed Camp Hughes.

The work of replacing the wounded and killed men began immediately. In fact, recruiting for a second division of Canadians had begun as early as October 1914, before the first division left for Britain. There were 15 infantry battalions and all the supporting units that the division would require. During 1915, a third Canadian division was recruited and sent overseas.

Many militia regiments wanted to raise one of the battalions and have it officially linked to the regiment. This was against the policy Minister of Militia Sam Hughes had developed. He could be persuaded, however, to make exceptions. The 8th Battalion, for example, was associated with the 90th Winnipeg Rifles from its inception and the Rifles raised other battalions that were used as reinforcements.

The Winnipeg Grenadiers, on the understanding the Winnipeg headquarters of the militia regiment would recruit all the officers and men needed to fill its ranks, raised the 78th Battalion. The Cameron Highlanders of Winnipeg raised the 79th Battalion and this was allowed after the Camerons’ Chaplain, Charles Gordon, visited the federal minister.

In his autobiography Postscript to Adventure, Gordon describes how Hughes explained the army was getting away from the idea of linking new battalions with the militia. Gordon argued the “clan feeling” of the Scots should be capitalized upon. “I expiated on their extraordinary cohesion, their loyalty, their pride of race…” These sorts of arguments carried weight with Hughes and he was convinced.

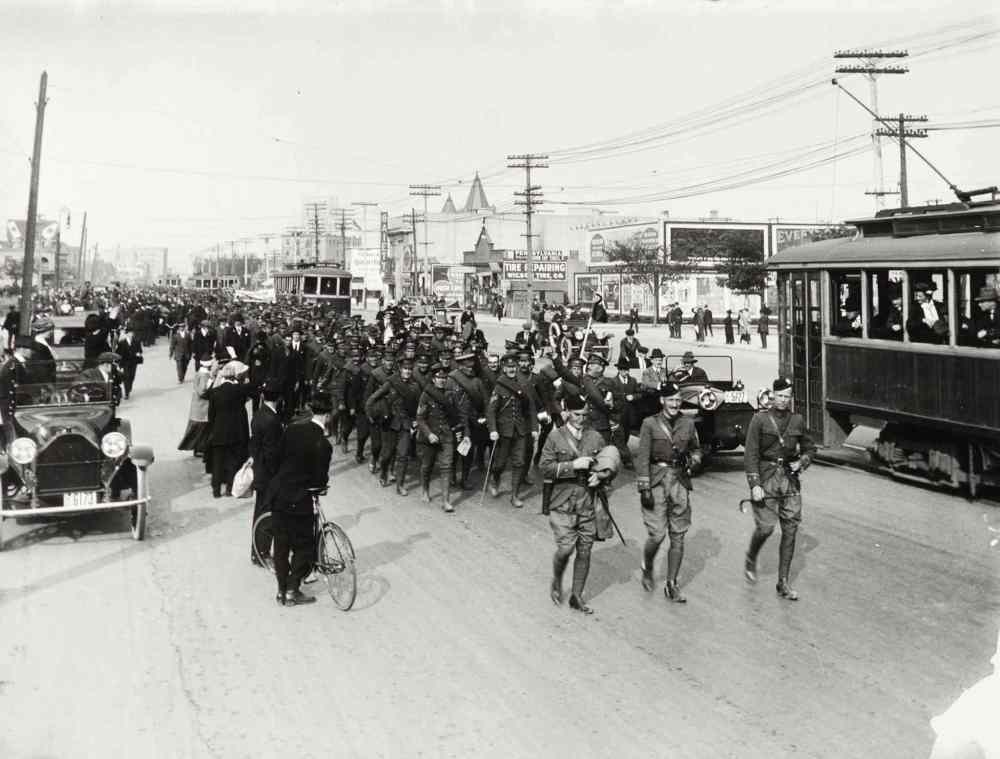

Some of the new battalions were sent overseas early as replacements. This was the case with the 32nd Battalion, the first troops of the Second Canadian Division to leave Winnipeg. On a bitterly cold Feb. 18, they marched from their billets in the Exhibition Grounds to Union Station at Broadway and Main. As they entered the station’s rotunda, the Telegram newspaper reported: “…the crowd came to life and cheers echoed up to the vast dome… the lads marched with unfaltering steps down to the subway and up onto the platform.”

The families and sweethearts of the men were there to say goodbye and there were plenty of tears. “God, isn’t it a shame,” one woman, the wife of an officer, said to her daughter as they left the station.

The tone of recruiting events was grimmer in the second half of the year because now everyone was aware of the slaughter taking place in Europe. That summer was the first time women handed out white feathers to men who were not in uniform. The official newspaper of the Methodist Church, the Christian Guardian, a pacifist paper before the war, shouted that every young man still a civilian must account “to his empire and to God why he is not in khaki.” These sorts of sentiments were heard each Sunday from the pulpits of the city.

At a recruiting rally in Winnipeg, Col. James Kirckaldy, a Brandon native who was wounded fighting with the 8th Battalion at Ypres, said “I have nothing but contempt for the man who can go but does not.”

He said he was sorry for people who had lost sons but “… had you been privileged to see them as we saw them, you would have been pleased that their death was glorious. I know of no better way to die that to die for your country.”

Kirckaldy, like many Ypres survivors, had learned a great deal about his trade during the battle. He commanded the 78th Winnipeg Grenadiers battalion and ended the war as a General.

Mayor Waugh, speaking at the same event, said, “I know what it means to let a boy go to the front. It was a great sacrifice, but this is a time of great sacrifices.” A few days before, at another event, he had said, “I would 10 times rather have my son lying dead on the field of battle than have him a coward and turn his back on danger.”

Waugh had two sons in the Lord Strathcona’s Horse at this time. One was badly wounded at Festubert in May 1915 and would be disabled for the rest of his life. The other died at the end of 1917, killed by a sniper. It was a very dark time and the people of Winnipeg showed enormous courage in the face of the horror of war.

Many of the new battalions went first to Sewell Camp, soon to be renamed Camp Hughes, for their initial training. During that summer there were 10,000 men under canvas at the western Manitoba camp. Waugh’s son, Alex, was there, a new recruit in the Lord Strathcona’s Horse regular army regiment.

It was cold and wet and he wrote to his mother in Winnipeg: “… for the love of mike get me a slicker… you can get one cheap at Eaton’s. In another couple of days I’ll be down with pleurisy if this rain keeps up.” He complained to his father that he and his fellow privates had to get up at 5 a.m. and run down the hill to take a cold shower before breakfast. “You can bet your life the officers don’t even get up to see if we go. It would kill them.” Alex would develop into a competent and popular officer during the two years that remained before he was killed.

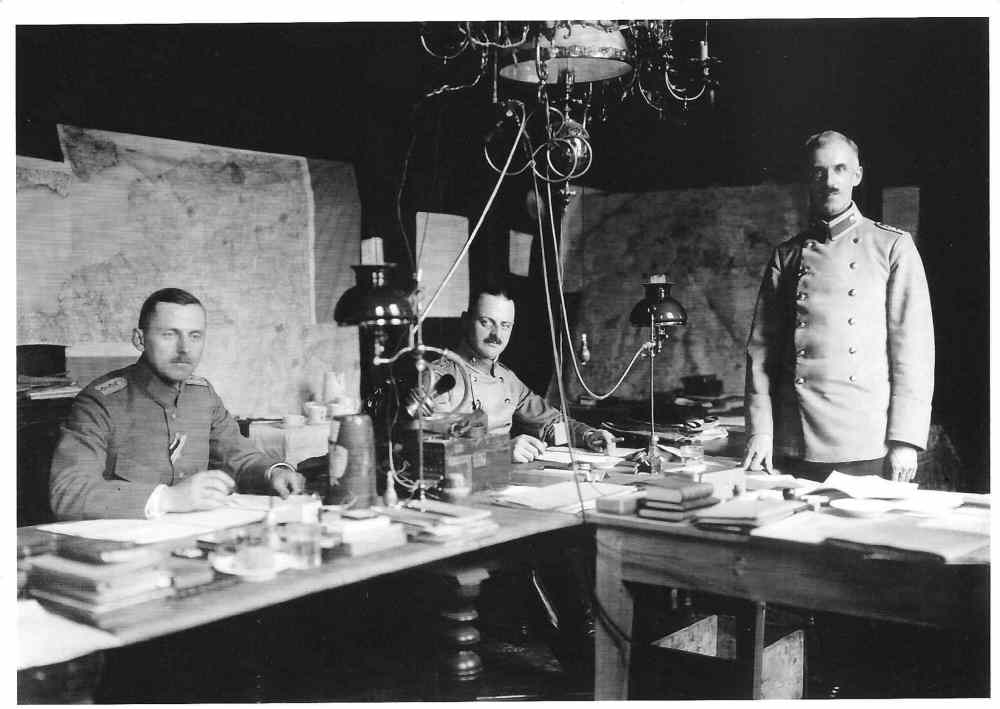

Premier Rodmond Roblin was forced to resign in the summer of 1915 after he was charged with fraud related to kickbacks from a contractor working on the new Legislative Building. (Foote Collection / Manitoba Archives Collection: Foote 540 NEG#N4397)

Premier Rodmond Roblin was forced to resign in the summer of 1915 after he was charged with fraud related to kickbacks from a contractor working on the new Legislative Building. (Foote Collection / Manitoba Archives Collection: Foote 540 NEG#N4397)

In Winnipeg, some things did not seem to be overly influenced by the war and politics was one of them. The 1915 legislative session began Feb. 9. Premier Rodmond Roblin had won his fourth majority the previous July, but the Liberals, under Tobias Norris, seemed inclined not to accept the victory. They charged Roblin’s party had used illegal and unethical means to win.

The Liberals had formed a loose alliance with a number of groups that wanted to see an end to the Roblin era. The Political Equality League supported and campaigned for the Liberals in 1914, having been promised if Norris won he would pass legislation to give women the vote. The Orange Lodge was also disenchanted with Roblin’s continued support for the school system that provided education in English and French, or Ukrainian or German if the numbers of students warranted it.

The most important developments in the session occurred in the Public Accounts Committee in March. The committee scrutinized government expenditures, including those connected with the new Manitoba Legislative Building rising on Broadway. Liberal committee member E.B. Hudson charged the group had been unable to do its work because requested witnesses and documents and plans had not been produced. On March 30, the last day of the session, the Conservative majority moved to pass the committee report that stated everything had been done correctly. Hudson proposed a lengthy amendment charging the contractor had overbilled the government by $800,000 for, among other things, material that had been ordered but never incorporated into the structure. Hudson also called on the premier to set up a Royal Commission to enquire into the matter.

The debate on the amendment lasted until 1:30 a.m. on April 1. It was expected the next morning Roblin would use his majority to pass the committee report without amendment, and ask the lieutenant-governor to prorogue the legislature.

But Lt.- Gov. Douglas Cameron, a Liberal appointee, took the unusual step of refusing to prorogue until Roblin had appointed a royal commission to look at the legislative building contracts. On the afternoon of April 1, Roblin rose in the house to announce the appointment of a royal commission under Chief Justice Mathers. It was one of the last times he spoke in the chamber where he had been a member for more than 20 years.

The commissioners questioned witnesses over the summer and concluded there had been wrongdoing. Basically, project contractor Thomas Kelly had overcharged the government on many invoices, been paid and then donated a portion of the money back to the Conservative Party to cover election expenses. Roblin resigned and an election was called for Aug. 6. Roblin and two of his former ministers were charged with fraud. Their trial dragged into 1917 when it was finally dropped because of Roblin’s failing health.

The election resulted in a massive victory for the Liberals, who went from 20 to 39 seats. The Conservatives elected only four members, three of whom were from Franco-Manitoban ridings where voters feared the Liberals would abolish the bilingual school system, which they did. The Conservative Party would not form a government in Manitoba for over 40 years.

The magnitude of the government’s defeat may have resulted from the contrast between the political chicanery being revealed and the sacrifices the province’s young men were making in the name of democracy in Belgium.

The brutality and horror of the war became clear to the people of Winnipeg in 1915. For the most part, they reacted with courage and determination, showing themselves willing to do what it would take to win.

History

Updated on Saturday, September 5, 2015 11:28 PM CDT: Corrects dates of battles of Festubert and Givenchy.