Great War required great effort

Winnipeg women made enormous sacrifices and contributions while sons, husbands and brothers were fighting and dying overseas 100 years ago

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 05/08/2017 (3142 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Jim Blanchard is the author of Winnipeg’s Great War: a City Comes of Age. Three years ago, he wrote about the onset of the First World War and its impact on Winnipeg. He has continued to examine life in Winnipeg in the subsequent war years, with this instalment looking back at 1917.

By 1917, thousands of Winnipeggers had already volunteered to fight and many had lost their lives.

And while Canadian troops — including Winnipeg-based battalions — proved their valour at Vimy in April, the debate over conscription boiled over at home. The sacrifices weren’t only mounting on the front lines, but in city warehouses and personal bank accounts.

Through donations to organizations such as the Red Cross and the Patriotic Fund, and by the purchase of Victory Bonds, the city had made huge financial contributions. Manitobans purchased $32 million worth of the bonds from the 1917 issue alone, making the province second in the country after Ontario in per capita investment.

The women of Winnipeg, working in organizations such as the Imperial Order Daughters of the Empire and the Red Cross, supported the war effort, providing tons of hospital supplies and “comforts” such as cigarettes and reading matter and many other necessities.

One example of the work done by Winnipeg women at the Red Cross supply depot located on the top floor of the Keewaydin Building, which remains standing on Portage Avenue East. The central clearing house for hospital supplies sent from Manitoba was entirely managed by volunteer women. By 1917, it had been brought to such a high level of efficiency that supplies were shipped directly from Winnipeg to Red Cross warehouses in Britain without first being inspected for quality in Toronto.

The women operating the depot, organized into a number of committees, purchased raw materials — 4,500 kilograms of wool and more than 18,000 metres of union flannel was a typical order sent to wholesalers — and then cut the cloth using the patterns mandated by the Red Cross. The cut cloth was then distributed to women across the province in IODE groups, churches and various First Nations.

These women sewed the pajamas, hospital gowns, surgeon’s gowns, towels, quilts, surgical dressings and bandages, among other items, and sent them back to the depot in Winnipeg. The items were checked and resewn if necessary, although this happened less and less as time went on. Bandages were sterilized by the nurses at the General Hospital and placed in sealed packages. Then large wooden packing cases — 2,200 in 1917 alone — were filled and delivered to the rail yards for shipping. The turnaround time from the receipt of an order to shipping was three weeks.

In addition, every week 600 pairs of socks, knitted by Manitoba women across the province, were shipped. Good wool socks were essential in the fight against trench foot, a debilitating disease contracted by men who spent their days standing in water in the trenches. It caused swelling and inflammation and could lead to gangrene and amputation. The Canadian army fought trench foot with adequate supplies of socks and whale oil applied to soldiers’ feet.

Women responsible for organizations such as the Red Cross depot proved their managerial skills and many felt that their accomplishments helped in the struggle for equality. Attitudes changed, as described by Winnipegger Mrs. Hugh Phillips, who later said that before the war “…We had ladies who wore white fox and rode in sleighs covered with fur robes. This way of life went with the war. After that there were no more “ladies.” We were all women, anxious for something to do.”

At the front, in Belgium and France, the Canadian Corps came together as a formidable and widely respected fighting unit in 1917. During the Battle of Arras in April, the four divisions of the Corps were given the job of taking Vimy Ridge. The Canadians were successful in attacking the formidable objective that had defeated previous attempts by the British and French.

After the impressive victory at Vimy, the Canadians continued fighting in the same area. In July, led by Sir Arthur Currie, newly appointed Canadian Commander in Chief, they took another formidable objective, Hill 70 near Vimy, inflicting heavy casualties on the German army.

In the fall, the Canadians moved north once again to the Ypres area in Belgium, where they had distinguished themselves in 1915 in their first action of the war. In what came to be called the 3rd Battle of Ypres, they fought beside the British and other British Empire troops. The final objective of the year was Passchendaele. For weeks, Australian, New Zealand and British troops had struggled through a battlefield that was a mass of water-filled shell holes dotted with machine-gun pillboxes. The Canadians and two British divisions made the final assault at the end of October and by Nov. 10 Passchendaele was taken. In all, 15,654 Canadians were killed or wounded during the 3rd Battle of Ypres.

Battalions bolstered by many Winnipeggers, including the 8th Winnipeg Rifles, the 27th City of Winnipeg, the Cameron Highlanders, the Winnipeg Grenadiers and the 44th Battalion, all took part in the 1917 fighting along with the rest of the Canadian Corps. Winnipeggers were also members of many other units. At the end of the year, the Canadian Cavalry Brigade participated in the Battle of Cambrai and the Fort Garry Horse and the Lord Strathcona’s Horse, both regiments with large numbers of Winnipeggers, suffered casualties. Day after day Winnipeg newspapers carried lists of the dead, and a steady stream of wounded local men whose fighting days were over returned to the city.

Since 1914, Canada’s army had consisted entirely of volunteers. But by 1917, as the numbers of casualties mounted and volunteer numbers fell, support for conscription grew. In April and May, Canadian casualties numbered 23,939, but only 11,790 new volunteers signed up. Across the country, citizen groups, such as Winnipeg’s Citizens Recruiting League, had been lobbying the government to do a national registration of potential draftees and introduce conscription. The government was hesitant because of concern that widespread opposition to conscription in Quebec and other provinces would divide the country.

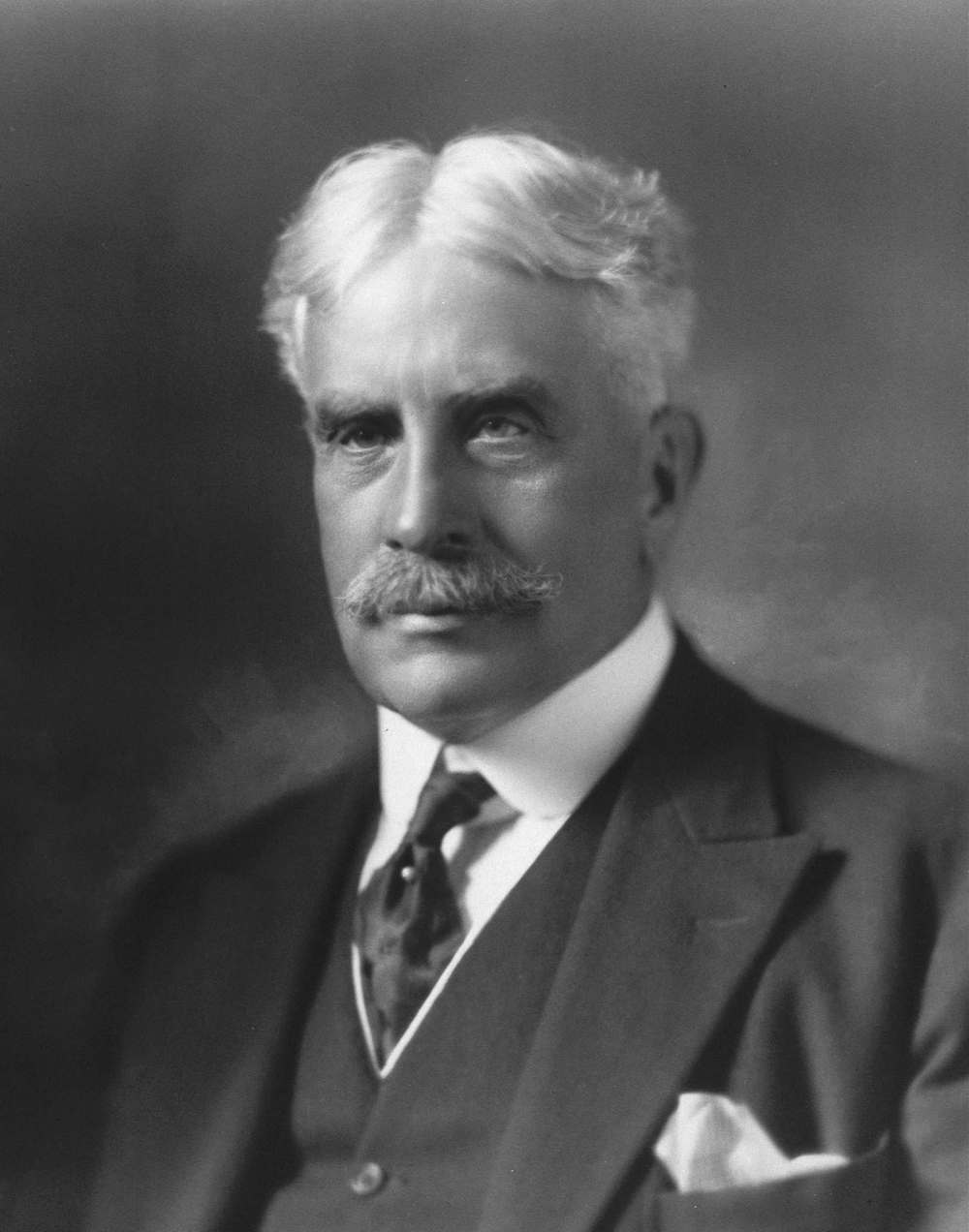

Prime minister Robert Borden slowly came around to the view that conscription was necessary, regardless of the political cost. On Aug. 29, 1917, Parliament passed the new Military Service Act by a vote of 119 to 55. Former prime minister Wilfrid Laurier and most francophone members voted against the act.

There was anti-conscription feeling and vocal opposition to conscription and its companion, registration of potential draftees, in English Canada as well. Some of the leaders of this movement were Winnipeggers.

Before the outbreak of war there was anti-war feeling among some Canadian Christians. Three denominations, the Quakers, Mennonites and Doukhobors, were officially exempted from conscription by the government as their beliefs prohibited them from fighting. Other groups were not officially recognized and when conscription began in 1918, some members of groups such as the Jehovah’s Witnesses were subjected to rough treatment and imprisonment for refusing to put on the uniform after being called up.

Meanwhile, the Canadian Presbyterian and Methodist Churches had passed anti-war resolutions before the war. The Methodist Church’s newspaper, the Christian Guardian, was solidly pacifist but when war came most churches revised their positions and encouraged members to enlist and fight, arguing that the war was a crusade against evil.

J.S. Woodsworth was a pacifist Methodist minister who had worked in Winnipeg at the All Souls Mission. He was the director of the Bureau of Social Research in 1916 when the movement toward conscription was beginning. On Dec. 28, 1916, he wrote a letter to the Free Press opposing the registration of men eligible to fight.

“As some of us cannot conscientiously engage in military service we are bound to resist what — if the war continues — will inevitably lead to forced service,” he wrote.

He lost his job over the letter and went to British Columbia where, for a time, he was the pastor of a church until his congregation, not comfortable with his views, asked him to leave. He spent the rest of the war working as a longshoreman.

Another clergyman who suffered consequences for his opposition to the war was William Ivens. At a meeting at Grace Methodist Church in early 1917, local Methodist clergy expressed their support for registration. Ivens, then pastor of McDougall Methodist Church, did not agree.

“I am a pacifist and I am opposed to war and war moves of any kind,” he said.

Ivens’ life changed drastically because of his pacifism. He was dismissed from his post at McDougall Methodist in early 1918 and became the editor of the Western Labor News. In July 1918, he founded the Western Labor Church and was imprisoned after the Winnipeg General Strike in 1919.

Women’s groups were divided in their positions on the war. Some, working in the IODE and Red Cross, threw themselves into the war effort, while other activists held pacifist beliefs. In 1915, a group of Canadian women founded the Canadian Women’s Peace Party that supported compulsory arbitration, disarmament and a League of Nations. Members of this group joined many other women from North America, travelling through submarine-infested waters to The Hague in April and May 1915 to attend the International Women’s Peace Conference, an unsuccessful attempt to stop the war.

In Winnipeg, the Beynon sisters, Francis and Lillian, were both pacifists and influential journalists — Francis at the Grain Growers Guide and Lillian at the Free Press. Read by women across the Prairies, the sisters both courageously opposed the war, supported women’s suffrage and other reforms that would make the lives of Canadian women better.

Lillian’s husband, journalist Vernon Thomas, lost his job at the Free Press in January when he left the press gallery in the legislature and walked onto the floor of the house to congratulate Fred Dixon on the anti-war speech he had just made during the throne speech debate. He and Lillian, along with Francis, opted to spend the rest of the war in New York. Francis Beynon wrote anti-war articles and the anti-war novel Aleta Day. The Beynon sisters returned to Winnipeg in the early 1920s.

Labour in Canada was also divided on the question of war. The Trades and Labour Congress of Canada passed a resolution at its 1911 convention calling for a general strike in the event of war, echoing labour groups all over Europe and North America. When war began, however, many union members and leaders joined the armed forces and supported the war effort in their respective countries.

The Winnipeg Trades and Labour Council had passed a resolution opposing conscription, and most labour leaders stated men should not be conscripted until wealth was also conscripted for the war effort.

In 1917, as happened in other Canadian cities, some local labour and socialist leaders formed an Anti-Conscription League in Winnipeg. Alderman John Queen, Bill Hoop, provincial MLAs Richard Rigg and Dixon, future Winnipeg Mayor Seymour Farmer and veteran labour politician Arthur Puttee were some of the leaders.

Dixon declared he completely denied the government’s right to ask him to register, telling a crowd of 4,000 at a meeting in December 1916 that: “National Service is the first step toward compulsion… Compulsory military service has been defeated in Australia (in a referendum) and it will be in Canada if it is put to a vote.”

Dixon, speaking during the 1917 throne speech debate a short time later, attacked the basic war aims of the government, saying that “the war did not involve the principles of freedom and liberty to the extent some people believed and bore all the earmarks of a struggle for power and possible setting up of a Russian militarism.” His remarks were greeted with shouts of “traitor” and “throw him in jail” from many of his fellow MLAs.

Rigg spoke next, claiming Britain did not really enter the war to save Belgium but to gain economic advantage over Germany. He argued British navalism was just as important as a cause of the war as German militarism and the basic reason Canadians were fighting was economic antagonism between Germany and Britain. Their fellow provincial politicians accused the two men of, “betraying their countrymen and assisting the Germans.”

Dixon became a lightning rod for the animosity the majority of Winnipeggers felt toward those who opposed conscription. The Winnipeg Board of Trade called for the Attorney General to take action against Dixon and Rigg in view of their “treasonable utterances.” On Jan. 19, both the Great War Veterans Association and the Army and Navy Veterans organization petitioned the government to have Rigg and Dixon resign their seats in the legislature. They also condemned city controller Arthur Puttee and three pro-labour aldermen.

At the end of January, a petition was circulated in his Winnipeg Centre riding demanding Dixon’s resignation. He promised to resign and run again if 25 per cent of his constituents signed the petition. A mere 50 names were gathered, suggesting many in his riding shared his views.

The opposition to conscription resulted in violence in Winnipeg. On June 3, a riot broke out at an Anti-Conscription meeting at the Grand Theatre on Notre Dame. About 1,000 people were present and a group of 250 returned soldiers occupied the front rows. Ignoring pleas from representatives of the Great War Veterans Association to let the anti-conscription speakers be heard, the soldiers hissed and booed F.J. Dixon and John Queen and broke up the meeting. Afterwards, there were several fights and scuffles in and around the building. Dixon had to defend himself against physical attacks in which he said, “…some heavy blows were struck but I don’t think any great damage was done.” The police escorted him and other speakers out of the theatre.

That support of the Trades and Labor Council for the League was not unanimous became clear at a council meeting on July 6 when a request from league member W.H. Hoop for aid was met with resistance and calls for a referendum on the subject. Hoop was reminded that many union members were at the front and some unions had declared that they supported conscription. The League continued its opposition.

The Canadian conscription legislation called for a national registration of men who were between 20 and 45 and medically fit. Men were called up according to classes defined by age and whether the person had dependents. The legislation allowed for exemptions; if, for one of a list of reasons the draftees thought they should be exempted, they could apply. Tribunals of local community leaders were appointed all across the country to rule on whether a man would be exempted or not.

Huge numbers applied for exemptions. In Montreal 93.5 per cent of draftees applied, in Kingston the figure was 96 per cent, in Toronto 90 per cent and in Winnipeg 94 per cent. In Manitoba, 3,050 men called up reported for duty. About 19,000 applied for an exemption. Another 20,000 men simply did not report and they were liable to be arrested by the Dominion police or the military police.

Half the Manitoba exemptions were denied. It was possible to appeal tribunal decisions to provincial courts and then to the Supreme Court. The numbers suggest a lack of enthusiasm across Canada, not just in Quebec.

Borden’s goal was to raise another 100,000 men for the Canadian Corps and, in the end, about that number were added. Of these, about 25,000 actually made it to France before the Armistice in November 1918.

In spite of the discord over conscription, civilian support for the war remained strong in 1917. About 100,000 people lined the city streets to cheer on the Decoration Day parade on May 23 in which returned men, veterans of previous wars and former soldiers of allied nations such as Lieut. Ishigura, a local man who had fought in the Russo Japanese war, marched.

On Aug. 4, 8,000 people packed the Industrial Bureau Auditorium for a ceremony to mark the third anniversary of the war. lt.-gov. James Aikins, premier Tobias Norris and other local dignitaries spoke. The audience sang Abide with Me, accompanied by the band of the Winnipeg Grenadiers, with gusto proving that, in the premier’s words, Winnipeg was inflexibly determined “…to continue until the allies are victorious.”

Jim Blanchard is a local historian. His book Winnipeg’s Great War, was published by University of Manitoba Press in 2010.