Bloody battles overseas, bitter battles at home

Chaos, corruption, controversy flared in Winnipeg while city's sons fought, died in the First World War

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 30/07/2016 (3420 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Jim Blanchard is the author of Winnipeg’s Great War: a City Comes of Age. Two years ago, he wrote about the onset of the First World War and its impact on Winnipeg. Blanchard returns to examine life in Winnipeg two years into the Great War.

By 1916, no one had any illusions about what the war in Europe was really like. Every day, the papers carried pictures of those who had died in the fighting, and badly wounded men were coming home, bringing their memories and nightmares.

A Pte. Cary told the Winnipeg Telegram one scene was always with him. “I see a big fat fellow aiming. I get him, and he jumps like a big jackrabbit performing in a pantomime. I laugh as I see him come down on his shoulder with his heels sticking up and wiggling. But nevertheless I fire again the wiggling stops.”

In April, the second Canadian division went into action for the first time. In March, the British had exploded six mines under the German trenches near the village of St. Éloi, south of Ypres. The mines created a moonscape of craters and tangled wreckage. The British had pushed forward to a line between the craters and the German position. On April 4, they were relieved by Canadian troops including the 27th City of Winnipeg Battalion. The battalion came under heavy German shelling and suffered many casualties. On April 6, the Germans counter-attacked, and during the confused fighting, commanders were often unsure where the Canadian line actually was in relation to the various craters. The lips of the craters obscured the view of the artillery, and the weather prevented aerial reconnaissance. The battle, from April 4 to 16, cost the Canadians 1,373 men killed and wounded and ended with the Germans in control of all the craters.

The commander of the 27th Battalion, Col. Irvine Snider, from the Portage la Prairie area, was a veteran of the 1885 fighting in Saskatchewan and the Boer War, but nothing he had experienced in those conflicts prepared him for the Western Front. After six days without sleep trying to lead his men in a chaotic situation, he suffered a nervous breakdown. His medical file recorded that he “… naturally felt the loss of his men personally. On retiring to billets felt naturally depressed and fatigued, but it was only when he saw his bed that he went all to pieces and broke down and cried.” After spending time in hospital, he was transferred to England to command replacement troops during their training.

St. Éloi was a fiasco, and some called for the removal of two Canadian generals, R.E.W. Turner, the division commander and Huntley Ketchen, commander of the 6th Canadian Brigade. Ketchen had been stationed in Winnipeg before the war, and he would return to the city where he was in command of the 10th Military District during the General Strike. It was decided, however, that to avoid conflict between the Canadians and British, it would be politic for the overall commander of the Canadian Corps, British Gen. Edwin Alderson, to take the blame. Gen. Julian Byng, who led the Canadians through the next period of fighting, replaced him.

Back home in Winnipeg, about the same time the 27th went into the line, there was a soldiers’ riot. During the winter of 1915-16 there were thousands of troops stationed in and around the city, training and waiting to be moved to England. On Saturdays, there was not much to do other than drink in the hotel bars along Main Street.

On the afternoon of Saturday, April 1, city police attempted to arrest an intoxicated soldier who had fallen down in the doorway of the Imperial Hotel at Alexander Avenue and Main Street. The officers on the scene had a difficult time getting their prisoner the three blocks back to the main police station on Rupert Avenue, where the Manitoba Museum now stands. The area was crowded with troops who believed they were answerable to the military police and not to the city constables. A crowd of some 3,000 soldiers and civilians soon filled Main Street, blocking traffic.

There were several pitched battles between the police, armed with their billy clubs, and the crowd armed with stones, ice chunks and bricks. The police station cells were soon full. Finally troops arrived from Fort Osborne barracks and things calmed down.

The next morning the crowd was back, demanding the release of the prisoners. There was another melee, during which all the windows in the station were broken. The city later presented the Department of Militia and Defence with a bill for $600, but it was never paid. When military police brought the prisoners out to be moved to barracks, some of them were grabbed by the crowd and hurried away.

The military did its best to downplay the incident, not wanting it to cause a rift between Winnipeggers and the soldiers, nor discourage recruiting. Magistrate Hugh John Macdonald handed out relatively light fines to rioters. But Canadian newspapers and the Associated Press in the U.S picked up the event. Stories in many American papers sensationalized the scene.

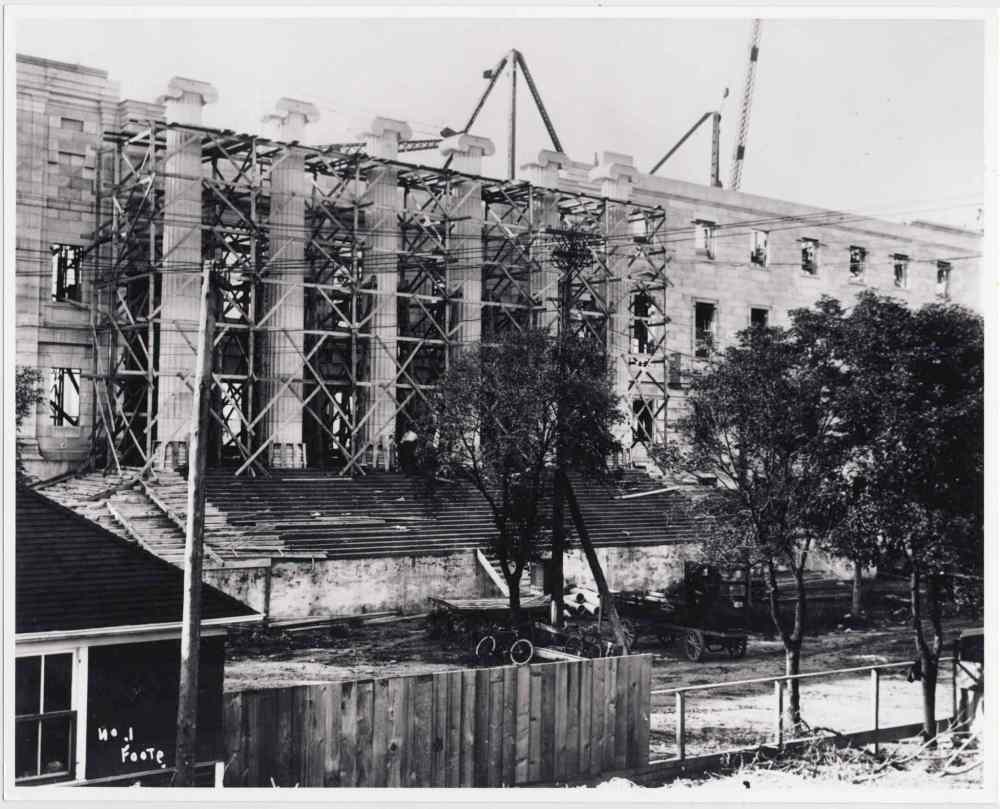

Politically, 1916 was a very active year. One of the busiest legislative sessions in Manitoba’s history opened on Jan. 6, 1916. The Liberal government of Tobias Norris had been elected on Aug. 6, 1915 with a record 40 seats. The ruling Conservative party was reduced to five seats from their former total of 25. The collapse of the Conservatives was the result of the Legislative Building scandal. A Royal Commission had uncovered massive corruption in the awarding of government contracts for the construction of the legislature and other public buildings. Inflated invoices were submitted and paid and then the contractor, Thomas Kelly, donated large sums of money to the Conservative party.

The scandal was in the headlines for much of 1916 as investigations and trials unfolded. Kelly was tried in June 1916, after having been extradited from the United States. He was convicted of the theft of $1.25 million from the province and sentenced to 2 1/2 years in prison. He was also ordered to refund the money but only about $30,000 was ever recovered.

Ex-premier Rodmond Roblin and two of his cabinet ministers, J.H. Howden and George Caldwell, were arrested and charged with conspiring with Kelly and several others to defraud the Crown through the inflated invoices scheme. They went to trial in July 1916 but the jury was unable to agree on a verdict. A year later the charges against them were dropped because both Roblin and Howden were seriously ill. Another former cabinet minister, Dr. W.H. Montague, had also been charged but had died before the case went to trial.

There were a number of other royal commissions during 1916, examining the alleged wrongdoing of the Roblin government. They revealed in some detail how old-style politics had been conducted. The tremendous sacrifices of Canada’s young people in Europe made voters at home less tolerant of political corruption; people were in a mood to clean up things.

The Norris Liberals had made common cause with a number of reform groups in the years leading up to their election in 1915. The Political Equality League, working for women’s suffrage, allied with Norris and Nellie McClung. Other League members were effective campaigners for the Liberals in the 1914 and 1915 provincial elections. Norris’s government passed the legislation to give women the vote and the right to hold office in Manitoba on Jan. 28, 1916.

The Temperance movement also supported the Liberals, who promised that if they were elected, prohibition would replace the Roblin government’s policy of strict regulation and the “local option,” which allowed individual municipalities to ban drinking within their borders. Prohibition came into force in Manitoba on June 1, 1916 and was the law until 1923.

The Norris government also moved to end a long-standing controversy by removing section 258 from the Manitoba Schools Act. That section embodied the principles of the Laurier-Greenway Compromise of 1896. In 1890 the government of premier Thomas Greenway had abolished the separate Catholic and Protestant school boards that had overseen public schools in Manitoba, replacing them with a secular, English-speaking system. Several years of court challenges and disputes followed as the French population attempted to overturn Greenway’s changes. The Laurier-Greenway agreement established a compromise that ended the strife. Among other things the agreement said that when 10 pupils in any school district spoke French, “or any language other than English,” they would get bilingual instruction in that language as well as English.

By 1916 this provision had resulted in a school system that had 126 French bilingual schools with 7,393 students, 61 German, mostly Mennonite schools with 2,814 students and 111 Ukrainian and Polish schools with 6,513 students. One in six Manitoba students were enrolled in bilingual schools. This situation was not popular with the province’s English-speaking majority and the Liberals had promised to end the system.

The Roblin government had refused to change the Schools Act and their position cost them votes as well as the support of the Orange Lodge, long a Conservative bulwark. Because of the education question, four of the five Conservative members elected in the — for them — disastrous 1915 election were from predominantly French-speaking ridings.

The minister of education, Dr. R.S. Thornton, introduced the bill to repeal section 258 in early February 1916. He argued that the bilingual policy made it extremely difficult to administer the school districts and to provide competent teachers for the different languages. This administrative argument was made along with loud declarations that Canada was a British country where every child should be fluent in English as well as learning British culture, values and history. Nativist feelings were running high because of the war and this influenced discussion of the schools issue. The Winnipeg Tribune editorialized that “…Our soldiers are fighting for British ideals. Are our legislators less patriotic that they should shrink from promoting British Canadian ideas by establishing English schools in every section of this British Canadian province.”

There was a bitter fight over the measure with French, Mennonite, Ukrainian and Polish organizations and leaders eloquently defending the existing system. French groups made the bilingual nature of the country an important part of their argument, invoking the British North America Acts and their rights as one of the founding peoples. In a pastoral letter, Archbishop Belliveau of St. Boniface said that he “…Would never cease standing for the rights of the French minority so long as they had not been recovered.”

Mennonites referred to the original agreements under which they had come to Manitoba, claiming the right to teach their children in their own language was guaranteed. The government claimed no such promises had been made in the 1870s. Because of the changes in the Schools Act, several thousand Old Order Mennonites eventually left Manitoba, resettling in Mexico and Paraguay.

Polish and Ukrainian, or Ruthenian (as they were sometimes called at the time) advocates stressed the importance of learning their national languages for their children’s “general welfare.” The head of the Ukrainian Catholic Church, Bishop Nykyta Budka and secular groups represented by people such as young Winnipeg lawyer J.W. Arsenych argued for retention of the existing system. This brought a barrage of nativist attacks down on their heads. J.W. Dafoe of the Free Press wrote “We can say with perfect propriety to the Ruthenian and Pole that if he is dissatisfied with our educational laws he can pack his trunk and go back to his happy home in war-torn Europe.” Bishop Budka was accused, not for the first time, of being a traitor and an Austrian-Hungarian sympathizer.

At the front, the last half of 1916 was dominated by the horrendous Battle of the Somme that raged in France from July 1 to the end of November. The Canadian Army went into the line on Sept. 21. Thousands died in the mud of the Somme battlefield. Particularly costly were the attempts to capture a line called the Regina Trench. On Oct. 8, it was the turn of Winnipeg’s 43rd Cameron Highlanders to attack. Led by their pipers they moved across the muddy no-man’s land. They were caught in the barbed wire and they suffered losses of 11 killed, 226 wounded and 125 missing, most of whom were also eventually reported killed. The Battalion’s colonel, R.M. Thompson, was wounded and died shortly after, when the ambulance he was being evacuated in was hit by a shell.

Most of the Camerons, including Thompson, were Winnipeggers and many were members of St. Stephen’s, their chaplain Charles W. Gordon’s Church.

The Canadians did eventually capture Regina Trench and another Winnipeg Battalion, the 44th, endured heavy losses in the fighting there. On Oct. 25 they felt they were let down when they went into an attack that was poorly planned and had insufficient artillery support. Close to half their number were mowed down by German machine guns. The battalion history Six Thousand Canadian Men describes Regina Trench at this stage as “…A flattened, shattered, meandering depression in the chalk… in many places blown twenty feet wide, and for long stretches, filled to within a foot of the top with debris and dead bodies — Canadian and German alike.”

It was another year of terrible slaughter and loss for Winnipeg. But the bravery of the Canadian Army was widely recognized and it would be in 1917 that they began to be rewarded with victories that, in the words of Manitoba Lt.-Gov. James Aikins, “…Led Canada’s astonished foes and admiring allies to realize that a new power had entered the lists.” And 1917 was also the year when the country ran out of willing volunteers to replace the men who died. This would lead, after a long and divisive struggle, to the imposition of conscription at the beginning of 1918.

Jim Blanchard is a local historian whose book, Winnipeg’s Great War, was published by University of Manitoba Press in 2010.