Removing Sir John A’s statue an important step

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 10/08/2018 (2678 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

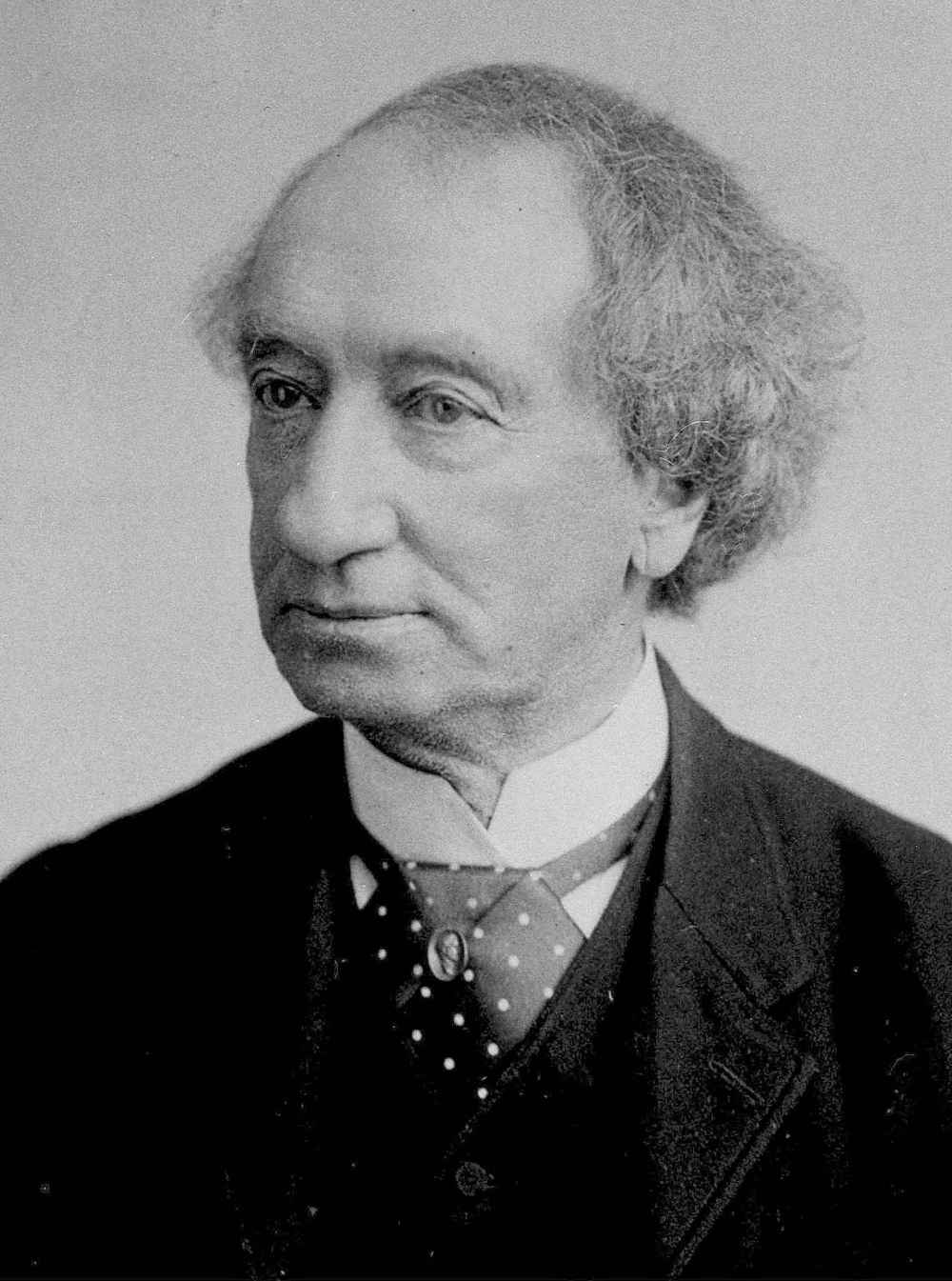

As you read this, the City of Victoria is removing a statue of Sir John A. Macdonald from the front steps of its city hall.

Public debates around monuments are always controversial. Picking who to memorialize, and the intention behind the act of memorializing a person or event, says a lot about the people doing it.

Try this: look around your community. Who is honoured here? What stories are being told? And, perhaps most importantly, what stories are missing or need to be told?

Now, do you see your community differently?

Monuments are not just reminders of stories but encouragements to tell more. Statues, plaques and signs tell us who we are, where we have come from, and where we are going.

These are sensitive issues for some; look at the passion surrounding the recent removal of Confederate leaders’ statues and monuments in the southern United States.

But the removal of a statue honouring Canada’s first prime minister from a city hall isn’t what this story is about. It’s about far more.

The move follows years of discussions the City of Victoria has held with the Esquimalt and Songhees, two Coast Salish First Nations it shares territory with. A number of years ago, the Lekwungen people — as they call themselves — invited the city to have a dialogue on what it means to live together.

The removal of the statue is a result of these talks.

Now, I’ve got to be honest. I’m tired of debating the merits of Macdonald. I’m exhausted with engaging the argument he is a “man of his time” and should be historicised, forgiven, or whatever else.

At any point in history, violence is violence. Macdonald swindled the Métis out of land, ordered the Canadian military to fire on families, and starved Indigenous communities into submission and removal. To call this anything but genocide is to ignore the facts.

No country in the world holds perpetrators of genocide in high regard. (Well, I guess there are a few – but I don’t think Canada would enjoy this company.)

I’m especially sick of the paranoia that removing Macdonald’s name off a building or award means he will be forgotten.

Every day, I drive my four-year-old past the CN railyards near our house, and he has asked me: “Why is the train here?”

My answer: “Sir John A. Macdonald.”

Macdonald’s legacy is fully entrenched in every inch of Canadian society, and its not going anywhere. It’s up to us to figure out what his legacy means for us.

The removal of a statue in Victoria isn’t about Macdonald. It’s about the future.

“If we’re serious about reconciliation as a city,” Victoria Mayor Lisa Helps told the Globe and Mail this week, “then part of our responsibility is to make sure that public spaces in Victoria not only start to reflect less of a colonial legacy but also start to have the signs and symbols and the presence of the Lekwungen people throughout the city.”

In other words, monuments are about commitments.

Victoria has chosen to be “serious” about reconciliation. To do this honestly comes with many steps: ethical, responsible, difficult steps.

Conversations are one. Action is another. The city now adopts the Lekwungen language alongside English on street signs and acknowledges its shared relationship with the Lekwungen people at all events.

One of the most exciting steps in this journey has been the conversion of a site at Beacon Hill Park, the 200-acre heart of the B.C. capital, into a traditional ceremonial longhouse run by the Lekwungen. The land will eventually be transferred to them, too.

These are not eternal solutions, but small gestures.

Victoria is located on unceded territories claimed by the Lekwungen. Stolen land. The removal of a statue and setting up some signs doesn’t erase that, but they are steps.

There are many parallels between Victoria and Winnipeg — some of its ideas, the Manitoba capital could even use. I, for one, can’t imagine how Ojibwa, Cree, or Michif languages on signage wouldn’t make our city better.

I also hear treaty and territorial acknowledgements at almost every event, from my daughter’s school, to the fringe festival, to sporting events. I hear Mayor Brian Bowman say it a lot, too. At times, I’m not certain we all know what that means, but it’s said — and that’s a step.

This is why monuments matter. They represent commitments. Commitments to the future.

This fall, the Manitoba government will have in its bureaucracy an application from citizens asking for space to create a statue of Chief Peguis on the Manitoba legislature grounds. There are monuments there to Queen Victoria, Louis Riel, Lord Selkirk, Nellie McClung and Ukrainian poet Taras Shevchenko, but none recognizing First Nations.

Nor is there an official statement the Manitoba government uses to recognize a relationship with Indigenous peoples. (While there is an acknowledgment the legislative building is located on Treaty 1 territory during official speeches, no other relationship is officially recognized.)

The fact there is a serious lack of Indigenous presence in Manitoba’s legislative epicentre is a statement.

A statement about our commitments.

To each other. And the future.

That’s what monuments are all about.

niigaan.sinclair@freepress.mb.ca

Niigaan Sinclair is Anishinaabe and is a columnist at the Winnipeg Free Press.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.