First Nation’s heart remains broken 49 years later Eight optimistic young lives on their way home to Bunibonibee Cree Nation were lost in a 1972 plane crash

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 29/09/2021 (1619 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

The cloudless blue sky above Bunibonibee Cree Nation is what Sarah McKay remembers most vividly about June 24, 1972.

McKay, who was 13 at the time, was too excited to keep her eyes off it. After cleaning up the house so it felt welcome, she spent much of the day tilting her chin up to the blue, in anticipation of her big sister’s return.

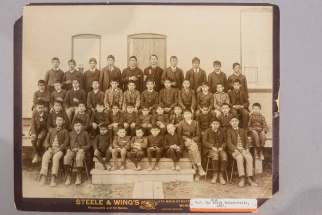

The start of the summer holidays marked a special reunion for the loved ones of students from Bunibonibee, formerly known as Oxford House, who were sent to residential schools and parallel learning institutions in southern Manitoba during the academic year.

I went swimming and I kept looking towards the southern area of the sky to see if I could see a plane coming, but no sign– no sign at all.” – Sarah McKay

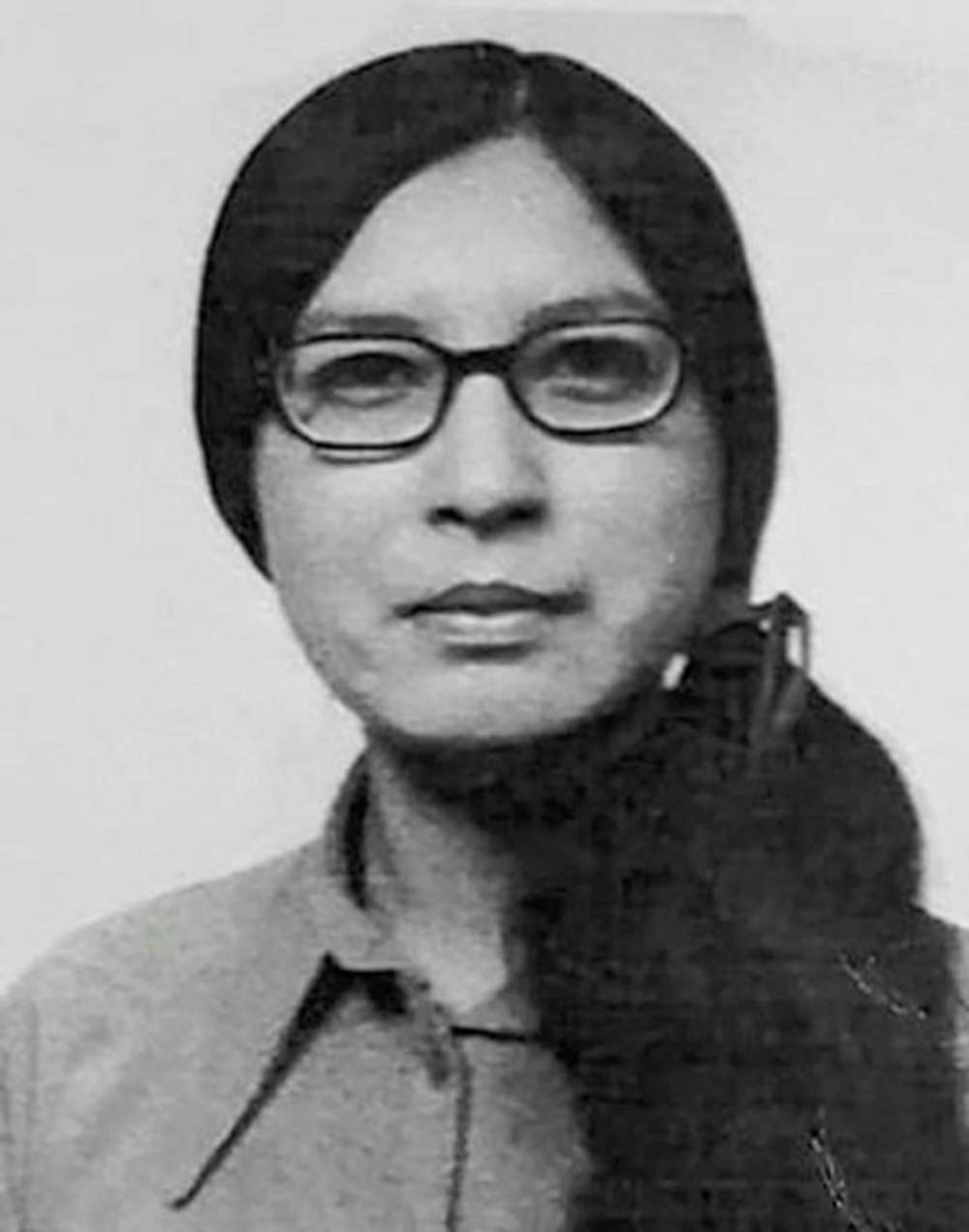

Families arrived at the airport in the remote, fly-in community that day for the long-awaited homecoming of Margaret Robinson, Mary Rita Canada, Ethel Grieves, Rosalie Balfour, Wilkie Muskego, Iona Weenusk and siblings Roy and Deborah Sinclair.

The Robinsons lived so close to the airstrip that McKay had planned to walk over to meet Margaret on the runway once she heard the Beechcraft-18 overhead.

“That day was so beautiful. When I did my house chores, I said to my mom, ‘I want to go swimming.’ I went swimming and I kept looking towards the southern area of the sky to see if I could see a plane coming, but no sign — no sign at all,” recalls McKay, one of the family’s eight children, born third in line after Margaret.

“I would go home and wait, thinking, ‘She should’ve been home already.’” – Sarah McKay

“I would go home and wait, thinking, ‘She should’ve been home already.’”

Community members heard on the radio later that night that there had been a plane crash in Winnipeg. It would take days before they got the confirmed names of the passengers aboard when it plummeted to the ground shortly after takeoff because of an engine malfunction.

Eight students, all of whom lived in Bunibonibee — although one teen was a member of Norway House Cree Nation — and Wilbur Scott Coughlin, the 47-year-old pilot from B.C., were killed.

Treaty No. 5 states that Her Majesty, The Queen “agrees to maintain schools for instruction in such reserves (in what is now known as northern Manitoba)… whenever the Indians of the reserve shall desire it.”

Despite a history of advocacy for adequate schooling in northern communities across the country, Bunibonibee’s children had access only to a Grade 8 education at the local day school in 1972. A high school diploma required a flight of nearly 600 kilometres south to Winnipeg and, likely, a bus trip to another community.

All but two of the group on the plane had been living with host families while attending Stonewall Collegiate Institute — not a residential school, strictly speaking — where anti-Indigenous racism was rife.

Ethel and Iona were students at Portage la Prairie Residential School, infamous for severe abuse, emotional neglect and harsh labour, as well as punishment for pupils who spoke their own languages instead of English.

Iona, who was 21 when she died and just months away from starting her training as a nurse, wrote about her harrowing experience as a northern student in the south in an award-winning essay published in the Free Press on Dec. 16, 1971.

In the essay entitled Two Different Worlds, she wrote, “On that first separation from my home in the north at the age of 14, I left with great expectations. I knew I was about to enter into a world that was completely different from mine but I never realized it would be so complicated and harsh.”

From 2008 to 2015, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada documented the physical, verbal, emotional and sexual abuse experienced by students who were taken to residential schools — which were designed to “kill the Indian in the child” — and detailed the ongoing intergenerational trauma as a result of the assimilative system’s brutality.

“(The 1972 crash) is a horrible tragic accident for everybody who was involved, there’s just no question about that.” – Celia Haig-Brown

The commission confirmed 3,200 residential school deaths, but the true number is estimated to be more than seven times that number. Countless others died travelling to or from school on planes, trains, buses, cattle cars and boats.

“(The 1972 crash) is a horrible tragic accident for everybody who was involved, there’s just no question about that,” says Celia Haig-Brown, an education professor at York University in Toronto, who studies decolonization.

“But it also stands as an example of the real complexities of the residential schools and their involvement in separating kids from their parents and from their communities.”

For a reason that remains unknown to Eleanor Brockington nearly 50 years later, the bus that took her Bunibonibee peers at Stonewall to the airport that Saturday afternoon didn’t pick her up.

The then-18 year old had made a last-minute decision to go home for the summer on the charter flight instead of travelling to Saskatchewan with her “second family,” the people she lived with in Stonewall.

She was told she would be picked up between 1 and 2 o’clock to get to the airport in time to board the 4 p.m. flight. When the bus didn’t show, she sobbed. There weren’t any adults around to take her to the airport, so she would have to take a flight the following week.

Brockington, now 67, lost her best friends Mary and Margaret, her cousin Wilkie and other close friends in the crash. All of the students from the remote community became friends because they were the only kids in Stonewall who spoke Cree fluently and shared the culture shock and homesickness.

Brockington says she felt numb that summer and it took many, many years to begin healing.

“Sometimes, I go visit (the site of the crash). I drive by slowly. Or I park and go walk by slowly, and see if I can feel their presence, because I miss them,” she says in an emotional phone interview from Thompson.

Mary, 18, was shy and obsessed with makeup; she had aspirations of becoming a hairdresser.

Margaret, 16, was a petite, lively young woman who liked to joke and tease her friends. When she was home in Bunibonibee, she made cakes, Jell-O and candies with her siblings and took care of her younger brothers. She boarded the plane with her new kitten, excited about introducing the pet to her family.

Rosalie, 16, was the only student from Norway House, although she grew up next door to Margaret in Bunibonibee. She was the second-youngest of nine children in her family.

Tannis Balfour, eldest of the siblings, says her heart breaks, knowing she never got to know her sister because she was much older and had been sent to Birtle Indian Residential School.

“I felt like somebody stabbed me with an icicle right in my heart,” says Balfour, now 81, about learning Rosalie had died in the crash.

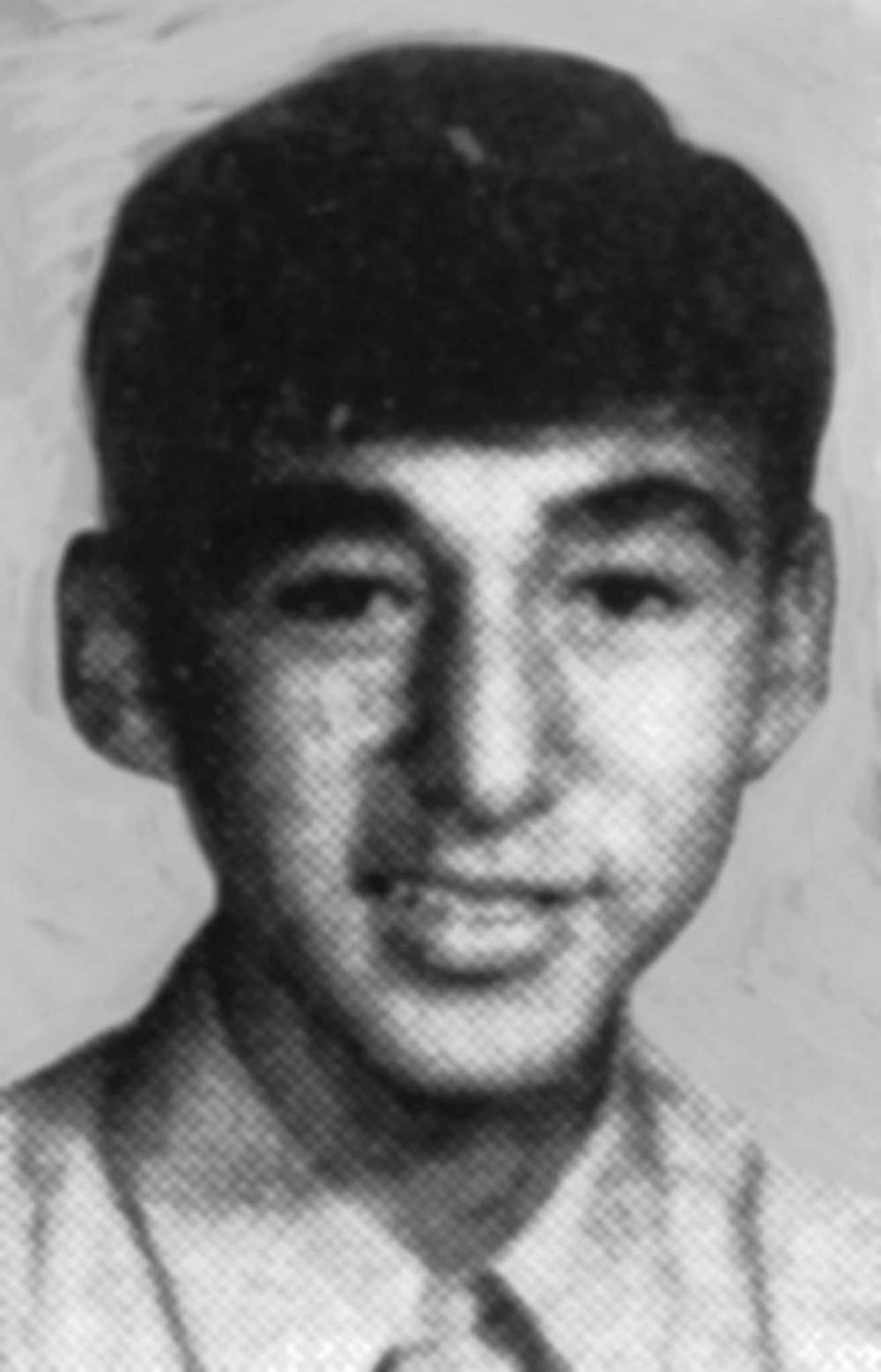

Roy Sinclair, 18, took a liking to living on a farm in Stonewall with his boarding family, where he learned how to milk cows and pile hay. His 14-year-old sister Deborah was known as a very kind and loving student who enjoyed cooking and sewing.

Wilkie, 16, enjoyed going to the movies with friends and listening to music — played loud — in his room. Lily Muskego recalls her older brother was quiet, but he always had a smile on his face.

Iona, 21, and Ethel, 17, were in Portage together. Iona was a talented writer from a family of 17 children who came third in a non-fiction writing contest run by the Free Press. The paper established an award in her honour after her death.

Ethel was a protective big sister and “gentle soul” who wrote home often to update her family about life in the south, including her participation in choir and her love for home-economics class.

It was about 4:30 when the students aboard the two-engine Beechcraft-18 owned by Ilford Riverton Airways left on what was supposed to be a three-hour flight home.

Eyewitnesses told the Free Press that day that both engines on the small aircraft failed as it banked while passing over the St. James area and made an emergency landing attempt on the Assiniboine Golf Club’s fairways.

The aircraft reportedly “dropped like a pancake” into a vacant lot between two houses, 426 and 430 Linwood St., igniting both homes and the surrounding area. There were no survivors on the plane, but all residents on the ground evacuated safely.

Wayne Wright grew up and still lives in a home around the corner from the lot. His late father, who worked in aviation, witnessed the crash. Wright says his father described hearing a sputtering noise — he called it “fuel starvation” — before the plane hit the ground.

Many believe the plane was filled with the wrong fuel, but the crash and its cause are not archived in Transportation Canada’s log of air-accident investigations.

Elenor Thompson, who was 12 when her sister Ethel died, recalls the proceedings after the crash being rushed and secretive.

Grieving parents, many of whom who could speak only Cree, were flown to Winnipeg with Oji-Cree translators from a different community to meet officials and sign papers to obtain minimal compensation for their children’s deaths, says Thompson, 61.

Before Thompson’s mother died several years ago, she sought to find out answers about the exact cause of the crash. Despite her efforts, including contacting local politicians, the family’s questions remain unanswered.

Chief Richard Hart considers June 24, 1972 and the days that followed to be the darkest in his community’s history. As far as Hart is concerned, the tragedy should be taught in history classes in every high school across Manitoba so it is never forgotten.

The students are buried together in a fenced-off area in the cemetery in Bunibonibee. A new memorial stone, which is engraved with student names and an eagle, was also unveiled earlier this year in Long Plain First Nation, close to where Iona and Ethel attended school.

But there is no memorial in Winnipeg. Many residents near the crash site know little, if anything about the tragedy. The current homeowner of the house at 430 Linwood St., which was rebuilt in 1973, says he would rather “let the past be in the past,” and not dig into the history.

University of Winnipeg historian Karen Froman is a member of Six Nations of the Grand River and is of mixed Mohawk and Irish-English-Dutch ancestry. She knew nothing of the incident until contacted about it by the Free Press.

Froman says she plans to discuss the tragedy with her students in Indigenous history classes when she brings up the fact that northern students still have to travel south to study.

“Far too many northern schools don’t go beyond Grade 8. Is a kid at that age really ready, prepared, to leave their home community to go hundreds of miles away to go live with strangers in a completely strange city, without any support systems?” she asks.

“The ultimate, underlying goal is to get us off the reserves and into the cities, and once there’s nobody on the reserves then there’s no need for a reserve. It’s a process of assimilation and elimination, to eliminate us as sovereign Indigenous nations on our own territories by denying us infrastructure, proper education, at home in our own communities.”

“The ultimate, underlying goal is to get us off the reserves and into the cities, and once there’s nobody on the reserves then there’s no need for a reserve. It’s a process of assimilation and elimination, to eliminate us as sovereign Indigenous nations on our own territories by denying us infrastructure, proper education, at home in our own communities.” – Historian Karen Froman

Following the crash, in 1973 Ottawa agreed to fund the expansion of Bunibonibee’s education system up to Grade 10. Programming was later expanded to offer courses up to Grade 12 so students could graduate at home.

“They had to lose their lives in order to be recognized that, as native people, we need to have the education available on the reserves so they don’t have to go out,” says McKay, who was only able to complete Grade 10 in her community.

In the aftermath of the tragedy, many parents forbade their children from travelling south to complete high school.

Pam Grieves, whose Auntie Mary died in the crash, says her grandparents spoke little about the incident when she was growing up because it was too difficult for them. Grieves says she knows only that after Mary’s death, her grandparents did not allow any of their children to go to school and, as a result, they got cut off from any kind of welfare or child tax assistance.

Last week, the community celebrated the opening of 1972 Memorial High School. Elder Rosie Weenusk, the only living parent of a student killed in the crash, cut the ribbon at the ceremony.

Thompson, who continues to grieve her sister Ethel, offered opening and closing prayers at the event.

“They would’ve been our elders right now, the elders of our community. Basically, we lost them, but as a community, we lost something because of that crash. The hurting is still there. We’re still dealing it,” says Thompson.

Next June marks the 50th anniversary of the crash. The milestone will be another stark reminder of the tragedy for Thompson and other loved ones who continue to mourn the lost lives on every holiday and break when students return to their families.

wfppullquote:

“People are still dealing with the legacy — the intergenerational trauma, that arose from the residential school system.” – Chief Richard Hart:wfppullquote

Many relatives of the students now work in the local elementary and high school in Bunibonibee. Thompson had a long career as a Cree teacher in the community who was passionate about language preservation and revitalization.

The 1972 Memorial High School is an upgraded building that can offer more choices and options for students, the community’s chief says.

“People are still dealing with the legacy — the intergenerational trauma, that arose from the residential school system,” Hart says.

“It means a lot that students can get their education at home, stay at home, be with their parents and graduate in the community. It means a tremendous amount of pride and, at the same time, without the fear of having to send out your kids at such a young age.”

— With files from Niigaan Sinclair

maggie.macintosh@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @macintoshmaggie

Maggie Macintosh

Education reporter

Maggie Macintosh reports on education for the Free Press. Originally from Hamilton, Ont., she first reported for the Free Press in 2017. Read more about Maggie.

Funding for the Free Press education reporter comes from the Government of Canada through the Local Journalism Initiative.

Every piece of reporting Maggie produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.