From out of the shadows Brian Sinclair's legacy will be visible for years to come, but there was so much we failed to see as he lived and neared death

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 20/09/2018 (2639 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

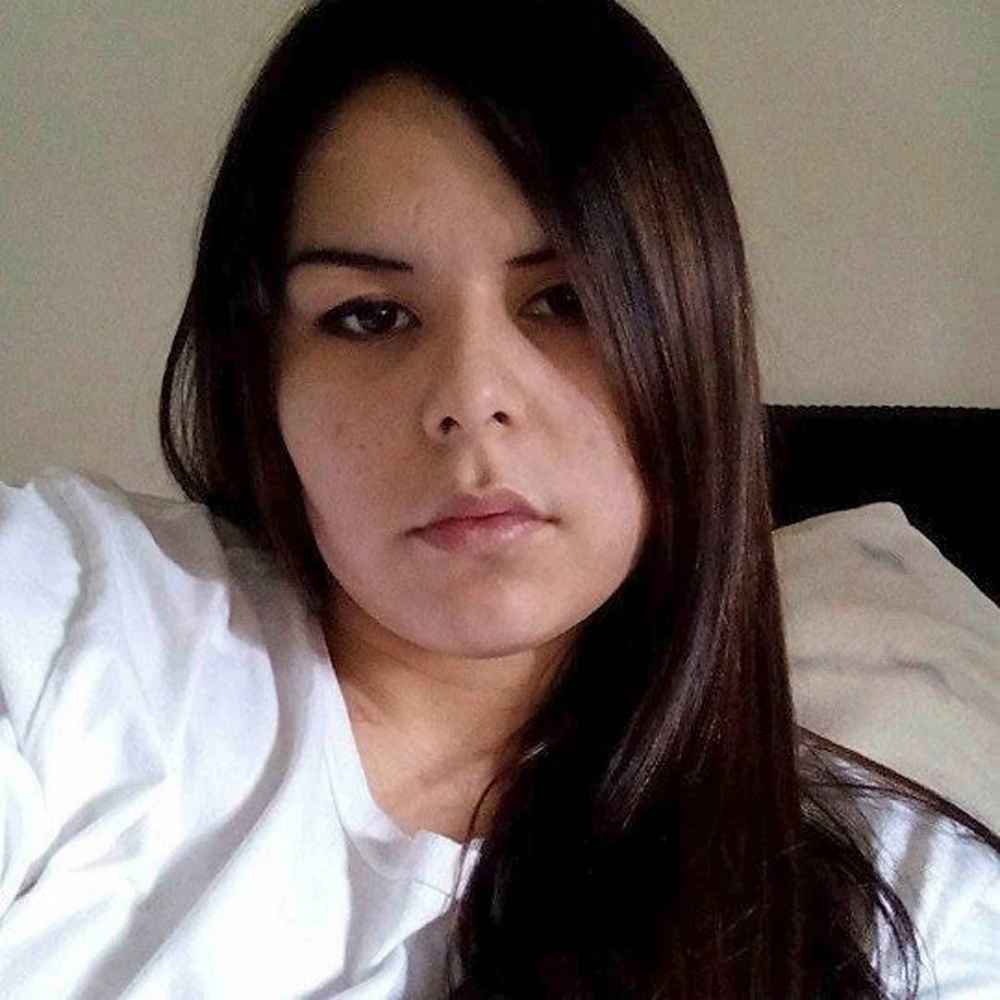

Ten years later, the ghost of Brian Sinclair still haunts the edges of Winnipeg’s consciousness. It whispers, moves, seems to shimmer; a phantasmic video image reconstructed from hundreds of pages of documents.

In my mind’s eye, veiled by the fog of imagination and time, this is how that ghostly video begins.

It’s a perfect September afternoon in Winnipeg, moments before 3 p.m. The skies above the city are gentle. Outside the Health Sciences Centre’s emergency room entrance, a white Handi-Transit taxi slows to a stop.

There is a man in a wheelchair. Hands resting on his thighs, clad in a dark jacket. The cab driver pushes his wheelchair to the triage desk, and then leaves. A man in scrubs, holding a notepad, walks over to greet him.

They talk, for just a few moments. Then Brian Sinclair turns around, and wheels his way to the waiting room.

He will be waiting a long time. Later, the people in charge of investigating his wait will arrive at a figure of 34 hours. But really, Sinclair’s wait is far longer than that: he will wait for care for a lifetime. He will wait forever.

In his right-hand breast pocket, he’d tucked a letter from a referring physician. It explained that there was a problem with his catheter that needed emergency attention; he was going to give the letter to a triage nurse.

But he never spoke to a triage nurse. He never got to show that letter to anyone.

When he was found dead on Sept. 21, 2008, slumped in his chair and still waiting for care, it was still with him. He might have waited even longer, had not a woman noticed, and insisted to a security guard that something was wrong.

This is the moment where the ghost-video stops, and the cold documentation of his death begins.

In the intervening years, we learned a great deal about the brass tacks of what happened. There were news stories, reports, press conferences. There was an inquest which heard evidence for 40 days in 2013 and ’14.

With the grace of time and the clarity it brings, there is still something Sinclair has yet to teach us.

Yet maybe, with the grace of time and the clarity it brings, there is still something Sinclair has yet to teach us.

Because the truth is, people like Brian Sinclair die all the time, in circumstances that ought to shine light on holes in systems. People who are vulnerable, who struggle, people who have been pushed to the margins.

The truth is, most of these deaths pass with little public attention. Most of the time, their truth is distilled into a number, added to a set of data. Most of the time, people are only as visible to us in death, as they were in life.

Yet for years, Sinclair’s death gripped Winnipeg news. Partly, this was due to the advocacy of his family and other supporters, who fought to make his death matter: to name the problems, get answers, make changes.

And partly, it was because there was a clear culprit to hold accountable, that being a health-care system that Manitobans know as flawed and frequently overburdened. One whose failures threaten to affect everyone.

But it’s more than that. It’s also the lonely stillness of his death was too uncomfortable for even the most comfortable parts of Winnipeg to ignore. The way he died was too painfully literal an image of a city’s shame.

He died surrounded by some of the best medicine in the world, yet felled by a simple infection. Like a man dead of thirst in an oasis, or hunger at a grocers: he died in plain sight, in the one place that could have helped him.

Above all, he died while dozens of people watched, and yet somehow didn’t really see him.

Instead, some saw what they projected him to be: a homeless man, seeking shelter. An intoxicated man, sleeping it off. He was neither of those things, nor should it have stopped him getting care if he had been.

Still, it was the fact that he was assumed to be those things that killed him. The infection took his body. Stereotyping a visibly struggling 45-year-old Indigenous man as homeless, or drunk, is what killed him.

So Sinclair died right in front of our eyes, both individual and, in a way, collective. Eyes that stared through him, as if he were invisible. Eyes that could not see him for the man he was, but only for what they created of him.

Ten years gone, and the truth of that image stands as stark as the day it happened.

This is a truth written over and over in this city, repeated in a multitude incidents of inattention. It is the same truth as when police officers found Tina Fontaine in a car with an older man, and let her go without checking.

And the same truth as in January, when a 29-year-old woman named Windy Gayle Sinclair was found frozen, dead in a Furby Street back lane. Just days earlier, she’d been taken by ambulance to Seven Oaks Hospital.

Somehow, her family says, she left the hospital without being discharged. Her mother was not notified.

These truths should be self-evident: that this city distributes its care and concern unequally, and this process does not require active dismissal. Stereotypes, assumptions, all of these conspire to shape who is protected.

Consider how, a decade after his name became news, it still feels like we never really knew Brian Sinclair.

We knew some things, of course. We knew, in excrutiating detail, the trials of his body: they were dutifully transcribed in news reports, for posterity. We knew about the state of his bladder, his bloodwork, his brain.

And we knew too, about how he lost both legs in the frigid winter of 2007, days after he was evicted from his apartment. He was found frozen, huddled against the wall of a church, where he’d collapsed seeking shelter.

So after his death, his body — by scalpel and by word — was dissected. A problem to be cut apart and disassembled. Something to be opened up and searched for a fatal flaw that could explain why he died.

But his personality, his story, the life that danced in his eyes: these things quickly slipped from public view.

The inquest into his death touched on it. Some news stories did explore his background, spoke to his family, gave the shape of him as a man who was soft-spoken and generous and liked to give back to his community.

Yet in the popular imagination, these things never quite stuck. We either never learned, or just forgot, that he was firmly independent, that he brought care workers gifts of fruit from Siloam Mission, where he volunteered.

He was proud of that work, and got up early each morning to wheel himself to the mission. His two brothers were often there, and friends too, and he passed happy days with them. Helping, laughing, being included.

We forgot that he was fully a part of a community: one he helped build, and that was built to include him.

And we forgot, over and over, that he was not homeless, that this was a quality ascribed to him only in his absence. For years, media and even, on one occasion, the Sinclair family’s lawyer referred to him that way.

This fact, the inquest later heard, frustrated care workers who visited Sinclair at Quest Inn, where he lived. They’d built deep bonds with him, and were years later still grieving his death; one considered him a friend.

Together, Sinclair and those carers had made a home. Not quite the picture that comes with the frame; there was no white-picket fence. But it was a home all the same, a place where Sinclair was cared for, and felt safe.

So even after Sinclair’s death, the indifference visited on him in the emergency room was revisited on his memory. The perception of him proved more resilient than reality: he remains what we perceive him to be.

That too should be part of his legacy, one that is still unfolding. We owe him a great deal: he paid the highest price for society’s sins, but in so doing left us a health-care system that is safer and better for all Manitobans.

Now, let’s remember who he was. Let’s open our eyes. Let’s notice who we are not seeing, and ask why.

melissa.martin@freepress.mb.ca

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.