Former Weston residents worry health problems linked to childhood exposure to lead

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 20/09/2018 (2638 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

On a nostalgic tour of his old Weston neighbourhood, Pat Werestiuk points out his favourite nooks and crannies.

There’s Pascoe Park, where he used to go skating. There’s the railway line cleaving Logan Avenue, where he used to hop cars. And there’s the backyard on Gallagher Street where his mom loved to garden, about a block from the former Canadian Bronze Company Ltd. smelter.

“We used to have cucumbers and everything, tomatoes, carrots. She used to can them, we used to eat them — there’s nothing like a tomato sandwich on bread with butter, fresh out of the garden,” Werestiuk recalled this week.

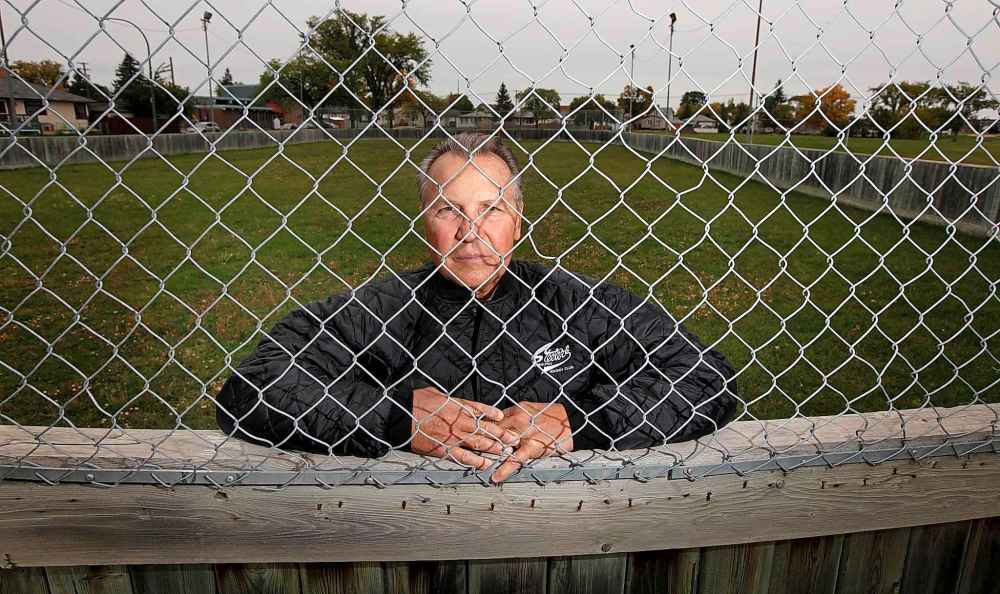

Weston sports field still closed

Winnipeg School Division spokesperson Radean Carter confirmed the field is still closed — and the nursery school to Grade 6 facility is hoping to have it reopened within the coming week.

Weston School (1410 Logan Ave.) closed off its adjoining sports field with a chain link fence Sept. 13, after a report surfaced about elevated lead levels found in its soil more than a decade ago.

School administration only heard about the buried lead report the day before, when alerted by media. They barred access to the sports field as a precaution, Winnipeg School Division spokesperson Radean Carter said at the time.

A week later, Carter confirmed the field is still closed — and the nursery school to Grade 6 facility is hoping to have it reopened within the coming week.

“The field will be reopened once our workers can lay some sod in bare spots. Due to recent rain, that’s just taking a bit longer than expected,” Carter wrote in an email.

The province’s sustainable development department is retesting the field to determine current lead levels. Sampling should be finished by the end of October, a government spokesperson said, and the results should be available by early December.

— Jessica Botelho-Urbanski

“But then you’re going, ‘Darn. This could have been poisoned with lead.’”

Werestiuk, 63, has prostate cancer, and wonders whether lead exposure in his youth may have made his body more susceptible to the disease.

He attended Weston School in the 1960s. Last week, school administrators restricted access to the sports field after news broke about a formerly hidden report, detailing elevated lead levels in soil samples gathered there in 2007 and 2008.

Eight years ago, Werestiuk took a heavy metals blood test and found his levels of lead and mercury were “off the charts.” (He shared the results with the Free Press.)

Werestiuk asked the province for funding to cover oft-controversial chelation therapy, which is said to flush toxins, such as lead, intravenously. Manitoba Health denied the request.

After news about Weston’s elevated lead levels surfaced again, Werestiuk believes the province should survey just how many of his former neighbours were exposed, and analyze whether they were more prone to health problems.

Weston students’ blood tested for lead in 1970s

In May 1979, about 300 Weston School students underwent blood testing for lead content, according to an archived Free Press article.

In May 1979, about 300 Weston School students underwent blood testing for lead content, according to an archived Free Press article.

A 1976 study – results of which weren’t made public until that year – found about 40 per cent of Weston students had “near or above danger levels” of lead in their bloodstreams and levels far higher compared to those of students at Lord Nelson School.

Three years later, the province re-did the blood testing to see whether the situation had improved. It’s unclear what the results were.

This week, the province told the Free Press there had never been any public health testing related to lead levels done at Weston, apparently missing or forgetting the aforementioned tests.

“We have no evidence that any human health assessments ever took place, nor are we aware of what steps, if any, were taken to address this issue,” a government spokesperson said in an email Tuesday.

In the 1970s, Lord Nelson School was located near heavy traffic on McPhillips Street, but Weston School (on Logan Avenue) had heavy traffic and heavy industry nearby. The Canadian Bronze Company Ltd. foundry was set up about a block away.

A teacher named Sandra Bea tried to get students a guided tour of the foundry at the time, “because they wanted to know what was poisoning them,” she said in the 1979 article. Her request was turned down.

The then-president of Canadian Bronze said his plant was abiding by government regulations, but wouldn’t answer a question about whether he would feel safe sending his own children to Weston School.

Four Manitoba cabinet ministers were tasked with investigating “the extent of lead poisoning throughout the province,” but it’s unclear when or if they presented their findings.

— Jessica Botelho-Urbanski

“Proving it, yes, it’s a tough thing. But the government should be looking at people who lived in Weston and if they have elevated lead levels, try and help them,” he said.

Shelley Costa, 42, also lived on Gallagher Street for 10 years and attended Weston School. She now has fibromyalgia, a disease known to cause chronic muscle pain and fatigue.

Both reported seeing an unusually high number of people they grew up with in Weston get sick later in life.

Costa is frustrated no one from the government told residents about possible lead exposure sooner.

“I’ve been so mad since I heard about it, but not surprised, unfortunately, because of the neighbourhood. You know, we’re not important. We’re not a rich neighbourhood, so it doesn’t matter. If we all get sick and die, oh well,” she said.

Costa is interested in getting tested for heavy metals.

“I didn’t think about it until (news) came up about all this lead in the soils in Weston. I cannot believe that they allowed us to continue to play on that playground knowing what they knew. Like how dare they risk us? And how many of us are affected negatively now because of their negligence back then?” she said.

“I’m really quite disgusted with all of it. I wish I could speak to the person that decided they were going to hide it.”

A government spokesperson said any residents who are concerned about their lead levels should consult with their physicians to request testing, which would be covered under provincial health insurance.

The province is retesting all the areas sampled a decade ago, to determine their levels and expects to provide up-to-date results by early December. The government hasn’t determined whether it will conduct a full health assessment of the affected neighbourhoods, but it didn’t rule out the idea.

“Regarding a community: this would require some consideration and an initial health risk assessment to determine if a health survey is warranted,” a Manitoba spokesperson said by email.

Another Weston native wants to see new soil testing done beyond Weston School, including places such as Pascoe Park, Weston Memorial Community Centre and Westview Park (widely known as “Garbage Hill”).

“That’s garbage. And that was put right in the middle of a housing development. So it’s something the government’s got to start looking at properly,” said Tim Sinnock, 60.

The province said Thursday it will be resampling as many locations as possible from the previous soil study.

Sinnock said he wasn’t shocked by the recently uncovered soil test results, due to a personal experience. Around 1970, his father asked that a ditch beside the nearby CP railyards — where children often played — be tested for toxins, he said. Officials later poured over the grassy area with concrete.

There was also some remediation work done at Weston School in the 1980s, the province confirmed, which included removal of lead paint, replacing of soil and laying down of cement.

Sinnock said he sees value in doing a neighbourhood-wide health assessment and he would participate, if necessary.

“I think it should be done, especially for the young kids that are there now,” he said. “Can we prevent this from getting worse?”

jessica.botelho@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @_jessbu