Marijuana could help opioid users stay on methadone treatment: study Users in Vancouver who consumed cannabis daily were 21 per cent more likely to stick with drug replacement therapy

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

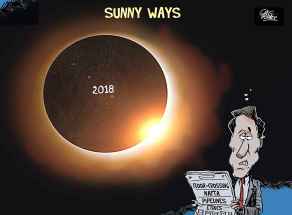

This article was published 20/09/2018 (2640 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Cannabis could play an important role in helping opioid drug users keep up with replacement treatments like methadone, suggests new Canadian research published today in the prestigious scientific journal Addiction.

Researchers from the B.C. Centre on Substance Use and the University of British Columbia retrospectively analyzed a sample of 820 people who used opioid drugs in Vancouver from 1996 to 2016. Everyone in the study population was involved in opioid treatment using medically prescribed drugs like methadone or buprenorphine that substitute for opioids and ease the ravages of withdrawal.

Subjects who used cannabis at least daily during their treatment were about 21 per cent more likely to stick with that treatment six months later, the study found.

People who are addicted to opioid drugs like heroin aren’t “getting high and having fun,” explains M-J Milloy, an epidemiologist and research scientist with the B.C. Centre on Substance Use and a senior author of the study.

“It’s not a recreational activity, but it’s the easiest way to stop withdrawal and to stop being sick. So the idea behind methadone is to replace that heroin with methadone or other agonist therapies.”

But methadone and other opioid replacement drugs are far from perfect, says Milloy. Dosing can be difficult and some users have adverse reactions.

“The other thing is, methadone is a painkiller, but not a very effective one — certainly not as effective as heroin and those other things,” says Milloy.

The study doesn’t explain why cannabis-using methadone patients might be more likely to continue treatment, but Milloy has a hypothesis.

“If someone goes off their heroin, and they go on methadone, well, their opioid use disorder is taken care of, but that chronic pain that they were using the heroin to address, that flares up,” says Milloy.

“They may be saying, ‘I’ve got to do something, I don’t want to go back on heroin, so let me try THC.'”

Past studies on the link between cannabis use and methadone treatment have found either no association or a negative association, but Milloy believes that could be the result of prevailing attitudes in the drug addictions treatment.

“(People) who are on methadone are typically required to provide a urine drug sample very regularly… And in many jurisdictions, evidence of drug use outside of methadone results in individuals being taken off methadone,” he says.

“So they’re not, quote-unquote, ‘failing’ methadone because they’re stopping taking it, or whatever, but rather they’re removed from methadone because they’re judged to be non-compliant with treatment.”

“I think the difference in Vancouver, especially in later parts of our study period, is that we don’t see that as much here… It’s unusual for a doctor in our setting to remove someone from methadone if they have THC in their urine.”

As with so many scientific studies involving cannabis, Milloy concludes that more research is needed. But he’s optimistic about the idea that “something about cannabis” could potentially help people transition away from opioid drugs.

“Certainly if you go to the Downtown Eastside in Vancouver, you’ll meet many people whose opioid use was born out of workplace accidents, car accidents, violence, physical trauma which resulted in chronic pain for which they were not properly treated,” says Milloy.

“And then many people, of course, turn to opioids. So it’s a possible hypothesis that in the transition between illicit opioids and (methadone or similar treatments), individuals turn to cannabis to manage their pain, and that helps them stay on their methadone.”

According to new data from the Public Health Agency of Canada, more than 8,000 Canadians died from “an apparent opioid-related drug overdose” between January 2016 and March 2018.

“The latest data suggest that the crisis is not abating,” wrote Canada’s Chief Public Health Officer Dr. Theresa Tam in a public statement this week.

Ultimately, Milloy says he’d like to do a full clinical trial to test whether cannabis could help treat opioid use disorder. Since cannabinoids can now be administered in capsule form, he says, it’s “quite possible that we could, for example, randomly assign individuals in a study to either receive a placebo, or receive a THC capsule or a CBD capsule along with their daily opioid agonist therapy.”

Canadian cannabis legalization increases the odds that such a clinical trial could actually take place, he adds.

“It makes it clear that very soon we’ll have the clarity we need around the regulations to be able to possess, administer, et cetera, et cetera — all the things that we need to do to test the promise of cannabis as a medicine.”

solomon.israel@theleafnews.com

@sol_israel