An open wound… 10 years later Nearly all inquest recommendations have been implemented, but Brian Sinclair's family says institutional racism -- the root cause of his death -- remains unaddressed

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 21/09/2018 (2638 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

If Brian Sinclair had been treated for a blocked urinary catheter at Health Sciences Centre 10 years ago, he would be 55 years old now and possibly still volunteering at Siloam Mission.

Friday at 12:51 a.m. marked the 10th anniversary of his death at the hospital emergency room. The Aboriginal man, a double-amputee who used a wheelchair, sat for 34 hours in the waiting room without being questioned or treated by staff. He had rolled into the ER and was immediately directed to the waiting room. He may have been dead for as long as seven hours by the time a family member of a patient noticed him and alerted medical staff. By the time they tried to resuscitate him, rigor mortis had already set in.

Sinclair went to the ER with a blocked urinary catheter, which resulted in a treatable bladder infection.

His death sparked an inquest and several reports into how a person waiting in the ER could be ignored by medical staff for 34 hours. HSC and the Winnipeg Regional Health Authority compiled internal reports. A Winnipeg police investigation was turned over to Saskatchewan prosecutors, who determined that no one should face criminal charges for Sinclair’s death. An inquest was held, and the judge, who listened to testimony from dozens of witnesses, made 63 recommendations aimed at reducing the chance of a person dying at an ER waiting room in Manitoba. Finally, the Sinclair family launched a $1.6-million lawsuit against the WRHA and hospital staff. The lawsuit has not been settled.

Sinclair’s death not only forced HSC to change its emergency room protocol, it sent shock waves throughout the province’s medical community.

In response to the death, HSC changed the design of the emergency department waiting room so that patients face the nurses’ desk. Almost immediately afterward, the WRHA initiated a wristband system at emergency rooms to help keep track of who had been spoken to in the waiting room.

In January 2016, two years after the inquest ended, only six of the judge’s 63 recommendations for the WRHA, provincial government and the public trustee had been completed.

Since then, 55 of them have been completed, including:

- ensuring staff intervene when they see someone vomit in the ER;

- ensuring that when primary care physicians send a patient to emergency that they phone the department in advance and verify a letter has been given to the patient to give to ED staff;

- Manitoba’s health authorities review emergency room floor plans to make sure waiting patients don’t face away from the triage desk;

- Probing whether it’s better to have doctors send information electronically to emergency departments;

- Have staff check on people in the waiting room regularly and wake them up at regular intervals.

Five other recommendations are partially completed and three remain outstanding.

Of the three outstanding, two of them — including one which would see a uniform protocol set up by all primary-care facilities for transporting patients with mobility or cognitive challenges to other health-care facilities — are in limbo while the province’s Shared Health organization is getting up and running. The organization is supposed to co-ordinate support to regional health authorities across the province and enable provincial planning and integration of services.

A final one, to look at having the office of the Home Care Co-ordinator be open seven days a week, has been put into the province’s review of home care.

Manitoba Health Minister Cameron Friesen was unavailable for comment for this story.

In a statement, a provincial government spokesman said: “Brian Sinclair’s death was a systemic failure of our province’s health-care system and prompted many changes to improve patient care and service delivery for all Manitobans, including the province’s Indigenous community.

“The inquest that probed the circumstances leading to Mr. Sinclair’s death produced 63 recommendations, 55 of which have been completed. Seven of the eight recommendations are in the process of being completed while another is being incorporated into a review of home care.

“While this is an accomplishment worth noting, our government is mindful that there will always be more work to do to make our province a more equitable and inclusive community, one that is free of bias and negative perceptions. We are committed to continuing this work, which includes our government’s ongoing reconciliation efforts.”

Lori Lamont, the WRHA’s acting chief operating officer, said two of the three recommendations that the province lists as incomplete, have already been completed by the WRHA, including the uniform protocol for transporting patients with mobility or cognitive challenges to other health- care facilities. Only the health authorities outside of Winnipeg have not finished them, waiting for the Shared Health organization.

“We have committed to make substantial progress on completing as many as we can,” Lamont said. “We have put in a lot of the new processes in place to prevent such a thing from happening again in the future.”

Lamont said the WRHA began working to fix problems before the inquest began, including instituting the wristband system.

“It is important at looking at what happened to Mr. Sinclair that there is no one simple thing or a simple solution… we’ve put in a number of different policies and procedures to make it extremely unlikely to take place (again).”

The Sinclair family hopes their lawsuit will give them more answers than the inquest did and result in further change in the health-care system.

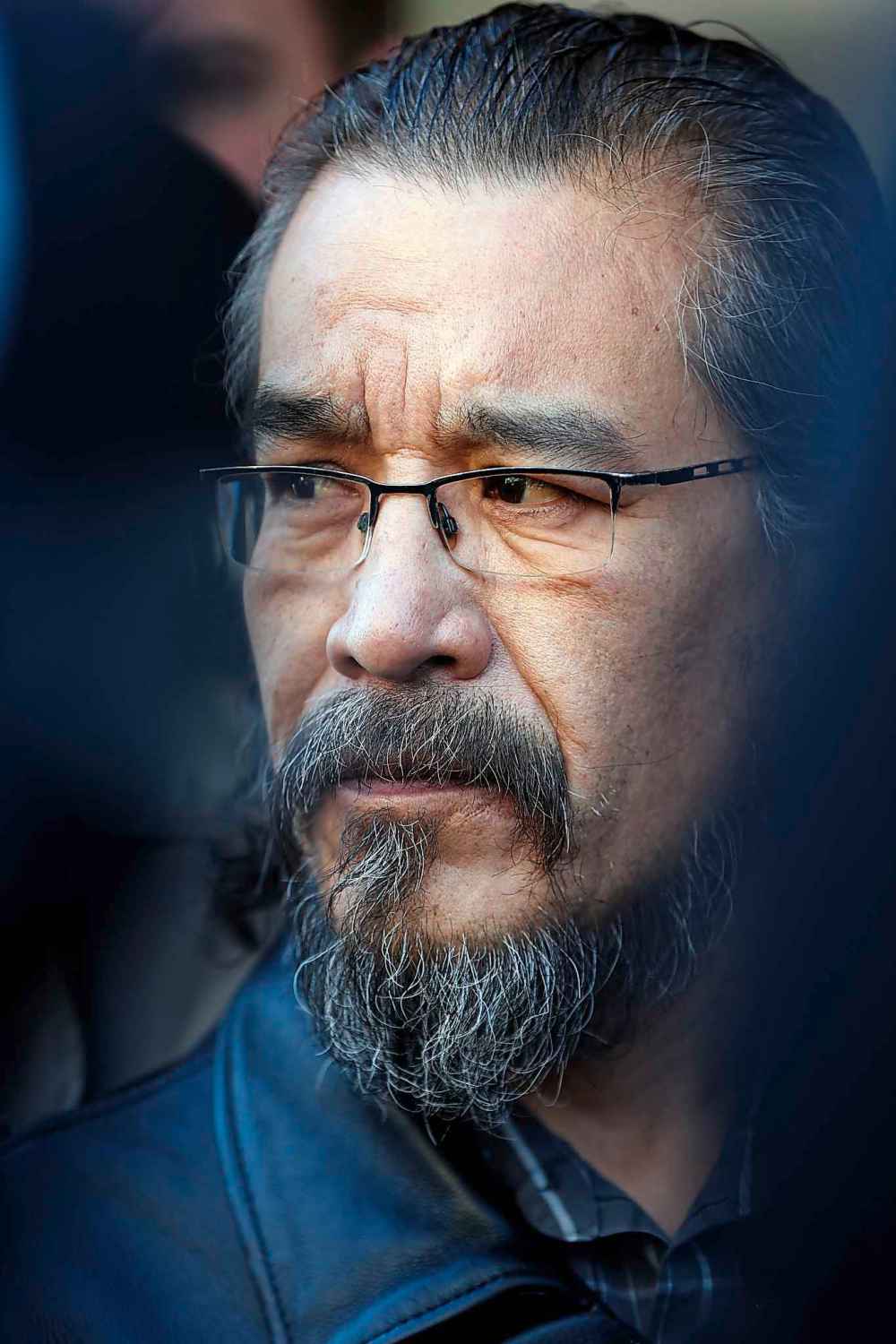

Robert Sinclair, Brian’s cousin, said they remain upset that provincial court Judge Tim Preston decided not to probe whether racism, poverty, mental health, and economic status were factors in the way ER staff failed to treat Sinclair, as was recommended by another judge. Preston ruled those issues were outside the scope of the inquest, but suited to a public inquiry that could examine societal issues. He did allow one outside witness to testify about systemic issues, including racial discrimination, in the health-care system.

Sinclair said the WRHA “did comply with most of the recommendations, but they forgot one very important thing.

“He died because of stereotyping and racism by whoever was at fault there,” he said.

“They never understood that issue and I can’t imagine them talking about it… the big question is how much of that played a role in Brian’s death? But they didn’t answer that in the inquest.

“Our one remaining question is, what have they done with (cultural sensitivity and racism) training? I think that was one of the root causes of his death and why he was ignored. We came to the table to seek the truth, and we still don’t have the truth.”

Vilko Zbogar, one of the lawyers who has acted for the Sinclair family, said he doubts whether the changes will prevent another tragedy.

“The WRHA came to the inquest, and through its own experts and staff said what the WRHA should do… and then the WRHA recommended they would do it. And (the WRHA) never touched on the thorny issue of racism,” Zbogar said.

“Of course they’ll implement their own recommendations, but we had hoped the recommendations would address the root issue: stereotyping and how to help people who are at risk of not being able to advocate for themselves.”

Zbogar said he hopes the lawsuit will continue where the inquest left off when it comes to racism.

“People just said, ‘We just assumed he was drunk,’” he said. “They didn’t assume he needed medical care. No one made that assumption about Brian Sinclair.

“The stereotypes were much more powerful than the medical cues.”

Emily Hill, a lawyer with Toronto-based Aboriginal Legal Services, which dropped out of the inquest when the judge decided not to explore the effect of racism on the case, said the 10-year anniversary date of Sinclair’s death must be “a sad time for his family.”

Hill said she knows from being a part of various human rights cases and inquests across the country that “Indigenous patients still experience discrimination which effect their case and the outcomes of their help.”

But Hill said it gives her comfort to know things have been changing since Sinclair died and his death may have prompted that change.

Hill said a few years after the inquest the Truth and Reconciliation Commission delved into racism and a few of its recommendations addressed health.

“At least we can acknowledge there is a problem and we can address it. It was through the persistence of the Sinclair family of keeping Brian’s death at the forefront at moving this.

“It is important to look forward and look back at the 10-year mark, but there is still a lot of work to do.”

Robert Sinclair said he hopes the lawsuit is heard in court soon so his family gets the answers they need about why Brian died.

“His mother passed away last summer,” he said. “His oldest sister is not in good health.

“I hope she is here to see the end.”

kevin.rollason@freepress.mb.ca

Kevin Rollason is one of the more versatile reporters at the Winnipeg Free Press. Whether it is covering city hall, the law courts, or general reporting, Rollason can be counted on to not only answer the 5 Ws — Who, What, When, Where and Why — but to do it in an interesting and accessible way for readers.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Friday, September 21, 2018 6:20 PM CDT: Fixes typos