Fit for a queen Fruitcake recipe has alleged royal origins, but family stories make it worth its weight in gold

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 09/12/2022 (1186 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Have you heard the one about monkey soup? How about sailing through the Canary Islands? Or the time a family member swiped the recipe for Queen Victoria’s wedding cake from the castle kitchen?

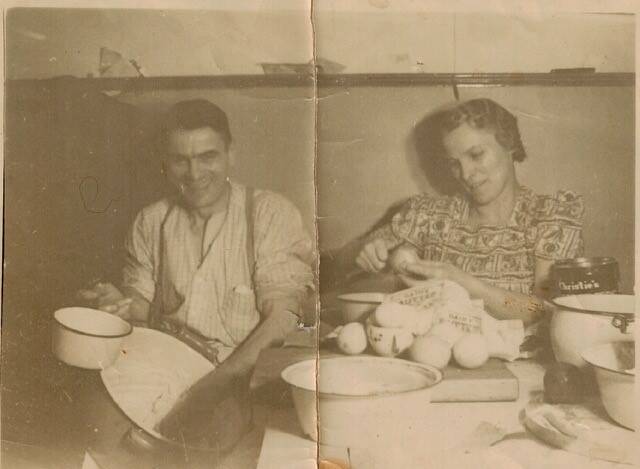

Marj Birley photo Septimus (left) and Nellie Murrell mix up a batch of fruitcake in the 1930s.

Septimus Murrell was a master storyteller. Every Sunday, after a meal of roast and potatoes, the grandkids would gather around gramp’s wheelchair and listen to tales about a hardscrabble childhood in rural England and an adventurous career cooking on British naval ships.

Whether all of those stories were entirely factual was completely irrelevant.

“He was the centre of everything for us kids; we weren’t underfoot for the people cooking, because we were beside him being well entertained,” his granddaughter Marj Birley says. “He tried to show us his world with his stories.”

It was a world of global travel and curious events that, upon reflection, may have been embellished slightly for his young audience — the aforementioned monkey soup story involved a passenger’s simian pet falling into a bubbling vat of broth in the galley kitchen, a tragedy discovered only after the meal had been served.

Homemade Holidays: 12 days of vintage treats

To cap off the Free Press’s anniversary year, we’re plumbing the archives for holiday recipes of yore. Follow along until Dec. 23 for a sampling of the sweet, strange and trendy desserts to grace our pages and your tables over the last 150 years.

Truth, especially in the case of family lore, is relative. Still, Gramp lived a storied life.

Born in 1887, Septimus was the seventh of 10 siblings — hence his name, which means “seventh” in Latin. His father died young and the kids laboured to support the family. The girls worked in service for wealthy families and the boys found blue-collar jobs.

For Septimus, that meant joining the merchant navy as an assistant cook in his teens. He sent money and jewelry home to his mother and worked his way up the ranks, graduating from the London School of Nautical Cookery in 1908. It was a job that took him to ports in Africa, Asia, North and South America and Australia — he enjoyed the last so much he left the navy to work on a sheep farm.

He intended to stay Down Under, but ended up in Stonewall after his brother immigrated to the area and purchased a 40-acre farm. The brothers ran a market garden and sold their produce in Winnipeg via donkey cart. It was in Stonewall that Septimus met his wife Nellie, who was working in the local post office.

He was conscripted into the First World War and married Nellie immediately upon his return. The couple opened a soda shop in Stonewall and later moved into Winnipeg, where Septimus spent the remainder of his working years cooking in the Eaton’s Grill Room.

MIKAELA MACKENZIE / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS Wedding pictures of Septimus and Nellie Murrell, who met and married in Stonewall.

“He used to bring home all the chocolates that had fallen on the floor,” Birley says. “This was the Depression… that was pretty good stuff.”

Septimus’s world shrank when he contracted polio in his 60s. He was hospitalized and spent time in an iron lung, losing the use of his legs and right arm. Storytelling became his main mode of travel.

In addition to colourful tales, Sep passed his love of food and cooking onto his grandchildren.

“He taught me how to bake as a child,” Birley says. “Even though he was in a wheelchair… he taught me verbally and through demos.”

MIKAELA MACKENZIE / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS Birley is the family archivist who has kept her grandfather’s recipe for ‘Gateau de Noel.’

The family fruitcake recipe was held in high regard. Septimus claimed it was the very same recipe used to make Queen Victoria’s wedding cake in 1840.

How the Murrell family got their hands on the recipe is another piece of family lore; perhaps the uncle who worked as a royal gardener had a connection in the kitchen or maybe it was published in a newspaper at the time? (A fun factual detail about the fruitcake served at Queen Victoria and Prince Albert’s wedding: it weighed 136 kilograms (300 pounds) and had a trend-setting two-tiered design that ushered in a new era of sky-high wedding cakes covered in white royal icing.)

Birley — an impassioned family archivist — has a taped and yellowed copy of the recipe for “Gateau de Noel,” written in her grandfather’s swirly cursive.

Septimus and Nellie served the cake at their wedding and made a batch every Christmas to mail home to family members in England. When he contracted polio, the tradition fell to Nellie and, later, his daughter-in-law Ruth.

MIKAELA MACKENZIE / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS A battered and much-loved handwritten copy of the fruitcake recipe, which dates back to the 1800s and has been a longtime Christmas and wedding tradition.

“Add a little more rosewater, Ruthie,” became his motto while instructing her how to make the rich, heavy cake. Generous glugs of rosewater and mixing the batter by hand were key to the process, according to Septimus.

When the task became a burden, Wendy Barker, Birley’s sister-in-law, took over.

“(Ruth) was probably the best mother-in-law you could ever have,” Barker says. “It feels like I’m paying back to carry on this tradition.”

She learned the recipe and where to buy the necessary ingredients — rosewater wasn’t widely available at the time — and has been making the fruitcake faithfully for the last 22 years.

Other than making use of a stand mixer, the process hasn’t changed much. Barker bakes the cake in November, usually on Remembrance Day, and lets it mellow on the counter for weeks to develop its complex flavour. On Christmas Day, the fruitcake is served to guests and doled out as gifts.

“Marj gets the most,” Barker says with a laugh. “And she does not share it.”

“That’s because I love it,” Birley says, adding that she keeps a ration in the freezer to enjoy year-round and will only pull it out for fellow fruitcake fans. “It’s like gold.”

MIKAELA MACKENZIE / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS Marj Birley (left) tries to make the annually baked cake last all year long. Sister-in-law Wendy Barker is the family baker, who says, ‘It feels like I’m paying back to carry on this tradition.’

Despite its regal origins, fruitcake gets a bad rap these days. It’s a divisive dessert that’s loved by some and loathed by many.

While the sisters-in-law share a fondness for the dense mixture of dried fruits and warm spices, their preferences differ. Birley is a booster for the dark fruitcake she grew up eating and Barker is a staunch supporter of light fruitcake — each served their preferred variation at their respective weddings.

So far, the kids and grandkids aren’t as keen on fruitcake as the elder relatives. When the time comes, both women are hopeful the next generation will step up to carry on the 182-year-old tradition that has become about much more than cake.

For Birley, the family fruitcake recipe is a delicious way to remember her beloved grandparents. For Barker, it’s an enjoyable act of service for the family she married into.

eva.wasney@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @evawasney

MIKAELA MACKENZIE / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS The Murrell family fruitcake has served as a Christmas and wedding tradition over the years.

Day 1 — Dark Fruit Cake, 1840

1 lb butter

1 lb Demerara sugar

9 eggs

1 lb flour

1 lb currants

1 lb sultanas

1 lb Thompson raisins

1/4 lb mixed peel (candied citrus peel)

3/4 tsp ginger

1 1/2 tsp allspice

3/8 tsp mace

1 1/2 tsp cinnamon

1 tsp salt

1/8 lb almonds

Juice of 3 lemons and 3 oranges

A little caramel extract and rosewater

Wash and dry fruit. Cream butter and sugar and work in the eggs one at a time.

Add the fruit, peel, spices, flour and almonds, mixing well. Mix in juices, caramel and rosewater. (Grandpa Murrell always encouraged the use of good amounts of rosewater.)

Put mixture into pans that have been well greased and lined with parchment or brown paper.

Bake at 250 F for two to three hours, depending on size of tins used. This recipe makes enough fruitcake to fill three square pans.

This recipe was submitted by Marj Birley and appears in the Free Press’s community cookbook Homemade: Recipes and Stories from Winnipeg and Beyond. We are now sold out of physical copies of the cookbook, but an e-version is available for purchase at wfp.to/homemade.

Eva Wasney has been a reporter with the Free Press Arts & Life department since 2019. Read more about Eva.

Every piece of reporting Eva produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.