Profit-driven policing Asset seizure by police not tied to criminal prosecution, skews motives of law enforcement, critics say

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 09/12/2022 (1094 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

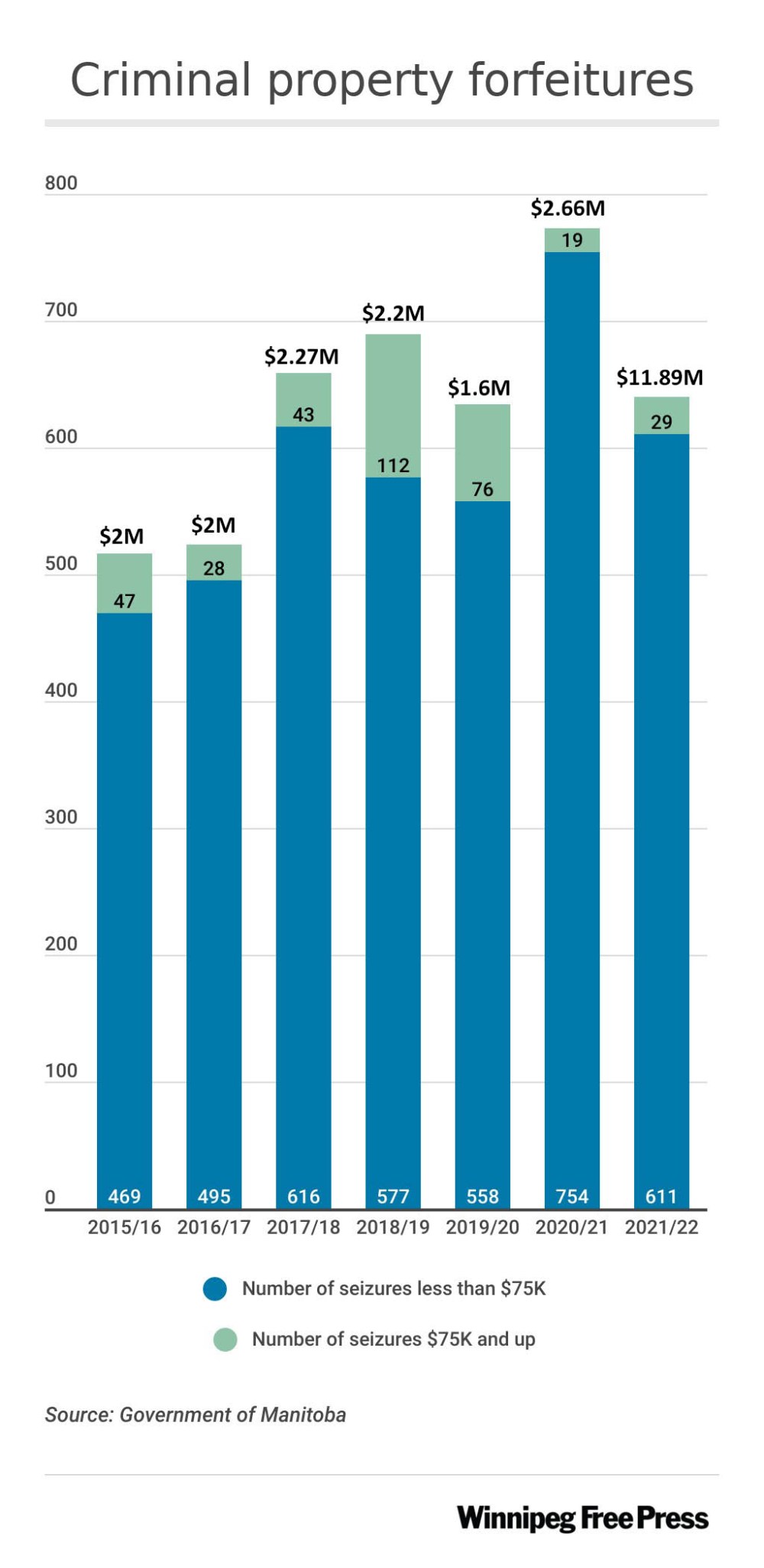

Manitoba’s Criminal Property Forfeiture Unit seized an estimated $11.89 million in tainted assets during the 2021-22 fiscal season — an increase of 346 per cent over the previous year, and far and away the largest annual haul since the unit’s inception.

That came after a decade which saw an eightfold increase in the proceeds of civil asset forfeiture in this province, with the Manitoba government twice loosening legislation to make it easier for the unit’s director to identify, target and seize alleged criminal wealth.

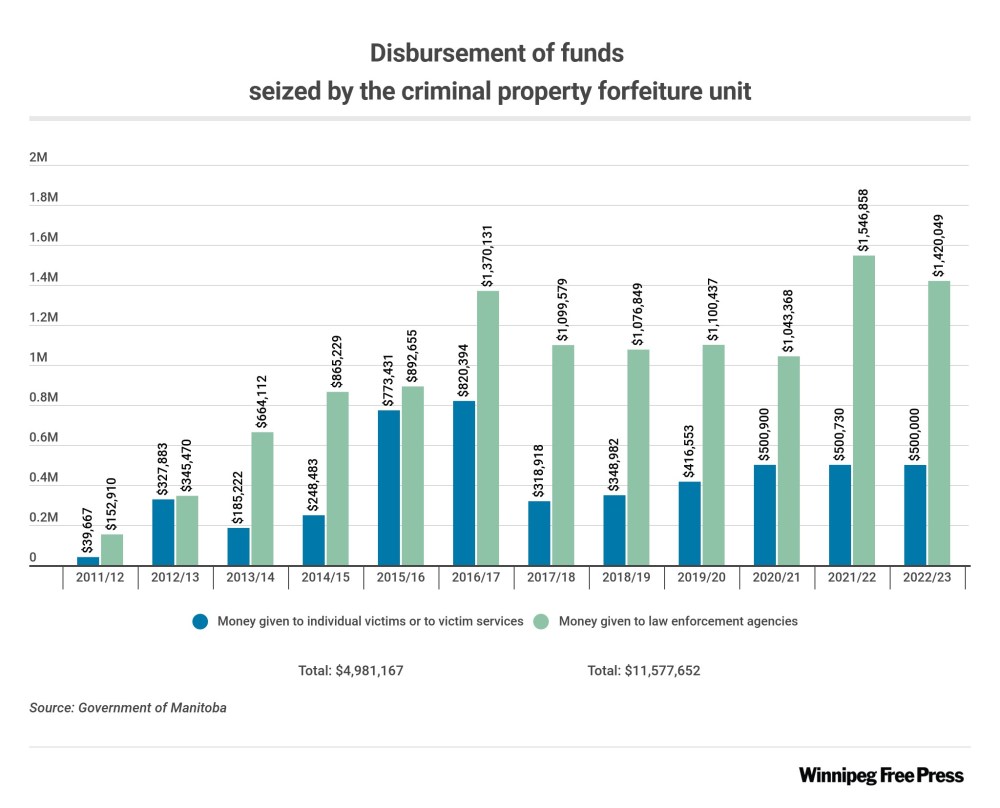

The vast majority of the seized funds were then dispersed to law enforcement agencies — primarily the Winnipeg Police Service and the RCMP — and were frequently used to purchase specialized tactical gear and surveillance equipment.

The latest legislative changes received royal assent in the fall of 2021, the same year that saw seizures spike to historic levels. In fact, the unit seized roughly the same amount of wealth in 2021-22 ($11.89 million) as the previous six years combined ($12.67 million).

In the majority of those cases, the seizures went uncontested by defendants, meaning the province was not required to prove in court — based on the civil standard of the balance of probabilities — that the assets were indeed tainted by illegal activity.

A person does not have to be charged with a crime, let alone convicted, in order to have their property seized. Forfeitures do not rely on criminal prosecutions, do not create findings of guilt or innocence, and are technically initiated against the property, not the person.

During the 14 years the unit has been active in Manitoba, its work has received limited scrutiny — from the public, the press and the courts.

There has been just one trial during its history, and only a few cases have ever risen to the Manitoba Court of Appeal — suggesting limited judicial oversight. No audit or full-scale review of its work has ever been conducted by the provincial government.

Now — on the heels of a record-breaking year for forfeitures, and armed with fresh legislative powers and additional investigative staff — the unit will soon be ramping up its operations even further.

Chief among those new powers are “preliminary preservation orders” and “preliminary disclosure orders.” The former can prevent a person from disposing of their property before a statement of claim is filed against them in court; the latter can require someone to answer questions under oath about the source of their property before forfeiture proceedings have even been initiated.

MIKE DEAL / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS Karl Gowenlock, a criminal defence attorney in Winnipeg, questions whether Manitoba’s Criminal Property Forfeiture Unit has become little more than a revenue-generating operation on behalf of the provincial government.

Advocates say these new legislative powers will help the unit crack down on money laundering, which is likely far more prevalent in Manitoba than most people realize, and will go a long way towards helping officials disrupt the financial dealings of criminal enterprises.

“We proceed only very cautiously, and we are very respectful of the rule of law. We have an obligation to follow what our legislation states,” said Melinda Murray, a longtime Crown attorney who took over as the executive director of the unit in 2020.

“We’re fairly certain that there is probably a lot more money out there… We do feel we’re only scratching the surface.”

But critics worry about the extent to which the new powers could erode privacy protections and due process rights in Manitoba, and question whether the unit has become little more than a revenue-generating operation on behalf of the provincial government.

“These are almost unprecedented powers that the government has given itself. In my view, they aren’t constitutional and wouldn’t stand up to a constitutional challenge,” said Karl Gowenlock, a criminal defence attorney in Winnipeg.

“This was passed with… very limited public debate or discussion, and I think that a large portion of the public would be quite shocked by it.”

Welcome to Manitoba, where crime pays — if not for the criminal, then for the police.

Forfeiture laws in Canada trace their roots back to global concern over money laundering in the 1990s.

That decade saw Canada introduce its criminal forfeiture laws at the federal level, with the government able to seize tainted assets post-conviction.

But by 2001, Ontario and Alberta had also passed provincial civil forfeiture legislation, whereby property related to an alleged crime could be seized without the need to prove an actual crime had been committed.

The rationale behind the new laws were to attack the financial underpinnings of organized crime and repair harm done to victims through direct payments and funding for supportive services.

Manitoba followed suit in 2004 with the Criminal Property Forfeiture Act. But those powers remained unused until 2008, when the provincial government passed its first major amendment to the legislation, officially creating the Criminal Property Forfeiture Unit.

A person does not have to be charged with a crime, let alone convicted, in order to have their property seized.

At the time, NDP Justice Minister Dave Chomiak said the new provincial body would work at arms-length from law enforcement agencies, and would likely do little more than cover its own operating expenses and maybe “earn a little bit of profit.”

But the unit quickly exceeded those expectations, seizing more property than was anticipated. This created a log jam in the courts due to the volume of cases, which led to a further legislative change — passed in 2012 — that resulted in the creation of “administrative seizure.”

Prior to 2012, any forfeiture initiated by the unit would be adjudicated in civil court. But following the 2012 amendment to the legislation, any property valued at less than $75,000 (excluding real estate) could now be seized administratively, without involving the courts at all.

The unit has seen rapid growth in its operations ever since, culminating in the 2021-22 historic spike in the estimated value of property seized, which followed an even further loosening of the legislation that regulates its work.

MIKE DEAL / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS Michelle Gallant, an academic at University of Manitoba who has studied criminal property forfeiture, is surprised at the extent to which these laws have been applied.

Michelle Gallant, a professor in the Faculty of Law at the University of Manitoba, has been studying civil forfeiture laws since the late-1990s, when she did doctoral research on how such regimes operated in the U.K. and the U.S.

“My idea then was that we’d never see this stuff in Canada, because I thought we had a very high-minded rights culture. So I was really surprised when a couple years later Ontario starts with the Civil Remedies Act, and then all of the provinces got on board,” Gallant said.

“And basically every province has them now… I have been very surprised at the extent to which these laws have been applied, and in some cases, used in very strange ways.”

In 2014, Gallant published a research paper — An Empirical Glimpse of Manitoba Civil Forfeiture Regulation — which looked at a random sample of 100 of the unit’s cases from 2009 to 2014.

“In almost all of the actions that were complete at the time of examination, the province was either partly, or wholly, successful in its forfeiture bid,” Gallant wrote.

“Notable too… is the frequency of default judgments, the failure of claimants to respond in any form to the forfeiture proceedings.”

JOHN WOODS / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS Melinda Murray, director of the Manitoba Criminal Property Forfeiture Unit, says up to 70 per cent the statement of claims filed by the unit in the Court of King’s Bench are resolved through default judgment, meaning the defendant in question does not contest the seizure.

According to Melinda Murray, “approximately 60 to 70 per cent” of the statement of claims filed by the unit in the Court of King’s Bench are resolved through default judgment, meaning the defendant in question does not contest the seizure.

Meanwhile, of the 5,677 administrative seizures initiated by the unit in its history, only 318 — or 5.6 per cent — were contested. The unit has also dropped 487 — or 8.5 per cent — of its seizures following a review of the evidence.

“We look at the evidence, whether or not we have enough evidence to prove the asset — whether it’s an instrument or proceed of unlawful activity — can we prove that. And secondly we look at interests of justice considerations,” Murray said.

“I think we’re a little bit more cautious than other jurisdictions. We pick and choose our cases based on whether we have the evidence to support it. We’re not going to throw everything against the wall and see what sticks.”

A Free Press review of 46 cases selected at random, all from 2021 and 2022, found that 43 were uncontested, two were discontinued by the unit, and only one was contested.

When the unit initiates a seizure against an individual’s property, its only duty to inform is to place a notice on its website, and to send a letter to the person’s last known address

While some might interpret an uncontested seizure as an admission that the property is indeed linked to criminal activity, lawyer Karl Gowenlock says the reality on the ground is far more complicated.

When the unit initiates a seizure against an individual’s property, its only duty to inform is to place a notice on its website, and to send a letter to the person’s last known address.

Gowenlock says he’s seen plenty of cases where the property is already seized and sold off by the time the person even learns the forfeiture proceedings have been initiated.

“They just have to send a letter to your last known address. That’s a problem given that a lot of people charged with criminal offences are often housing insecure or often moving addresses. Or I’ve had people in jail and they send it to their address in the community,” Gowenlock said.

Gowenlock says he’s seen plenty of cases where the property is already seized and sold off by the time the person even learns the forfeiture proceedings have been initiated.

“Plus there’s a notice on a website. But if you don’t know to go look at that, people can just get their stuff forfeited before they even know what’s happened. And if there was an explanation, then they’ll have to go King’s Bench and file a suit to try to recover it.”

In addition, Gowenlock says because civil forfeiture proceedings (against the property) often coincide with criminal prosecutions (against the person), it forces the accused into a fighting a war on two fronts, with many people having to prioritize their criminal defence.

“The biggest obstacle is that it really costs a lot to fight one of these in legal fees. And it’s not really something where one could do well representing oneself. It’s far more complicated than small claims court,” Gowenlock said.

“These are people who often do not have a lot of money on hand. Some people might have a very strong defence, but simply can’t afford to fight it.”

From 2009 to May 2021, Manitoba’s Criminal Property Forfeiture Unit seized $22.3 million in allegedly tainted assets and dispersed roughly $16 million in grants.

In press releases and political messaging related to the unit’s work, the province has consistently trumpeted the idea it is taking money away from criminals and re-investing it in support for victims.

But that narrative is complicated by the province’s own data, which reveals the overwhelming majority of that money — roughly 70 per cent — has been given to law enforcement agencies.

From 2011-12 to 2022-23, roughly $938,000 has been distributed directly to individual victims of crime, and a little more than $4 million has been distributed to Manitoba Justice Victims Services.

During that same time period police agencies were given roughly $11.6 million – with about 88 per cent of it being earmarked for equipment, training and programs, and the rest being further distributed to “community initiatives” through the respective police service.

The funding for individual victims and victims services has remained relatively static, whereas money funneled to law enforcement has consistently been on the rise. In 2011-12, law enforcement agencies received $152,910 in grants, and by 2022-23, that figure had risen to more than $1.4 million — an increase of more than 800 per cent.

In 2016, the Canadian Constitution Foundation did a cross-country review of provincial civil forfeiture regimes, alleging they “rarely” accomplish their stated aims and are “fraught with irreparable problems,” including the risk of seeking forfeitures “for the purpose of raising funds.”

Manitoba was given a letter grade of F, in part because such a high percentage of the money seized through civil forfeiture actions went to law enforcement rather than victims.

Brendan Roziere, a lawyer who — while a student at U of M — wrote about Manitoba’s civil forfeiture regime on the Robson Crim Legal Blog, said there was also a need to increase transparency on just what law enforcement agencies are spending the money on.

BORIS MINKEVICH / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS FILES In 2014, then-Manitoba Justice Minister Gord Mackintosh and then-Winnipeg police Deputy Chief Danny Smyth pose with a bomb squad robot, which was purchased with money from the forfeiture fund.

His research determined the largest individual recipient of grants from Manitoba’s Criminal Property Forfeiture Fund (where the money raised by selling off seized assets is stored) has been the Winnipeg Police Service.

High-profile purchases by the WPS include significant surveillance and tactical gear, as well as the 2021 acquisition of a robot dog from the U.S. company Boston Dynamics. Other police agencies, including the RCMP, have used grants to purchase a drone, rifles and tactical gear.

“Forfeiture can undermine the municipal government by allowing the police to make purchases outside their usual budget, with reduced oversight and possibly even in conflict with the priorities of elected officials,” Roziere wrote.

“The public has not been given opportunities to voice concerns or help set priorities and law enforcement has prioritized substantial surveillance and tactical equipment purchases, abuse of which is of heightened concern to citizens and brings into question how the funds are spent.”

Other concerns raised by critics and academics are the possibility that civil forfeiture regimes could create a perverse incentive structure for the police — the tendency for them to seize greater amounts of property knowing they’ll be more likely to receive larger grants on the back end.

This is of greater importance during an era that has seen increased militarization of police — particularly in Winnipeg, which in recent years has purchased a large stock of semi-automatic carbine rifles and a tank, and also operates a helicopter.

DREW MAY / THE BRANDON SUN FILES Brandon Police Service officers conducting a training exercise. The armoured vehicle was purchased in 2019 with proceeds from Manitoba’s Criminal Property Forfeiture Unit.

The Brandon Police Service also purchased a tank — styled as an “armoured response vehicle” — in 2019 with money secured through the province’s Criminal Property Forfeiture Fund.

Brian Kelly, an academic at Seattle University, conducted a review into five jurisdictions that used civil forfeiture extensively, and determined it “doesn’t work to fight crime” and is used to “raise revenue,” adding that police “appear to ramp up” seizures when “local economies suffer.”

That tracks with the experience in Manitoba, which saw an all-time record in the amount of assets seized in 2021-22, at a time when the economy was struggling in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic and inflation was on the rise.

In May 2019, the B.C. government triggered the Cullen Commission following multiple reports that concluded hundreds of millions of dollars in illegal cash was flowing through the province’s economy, particularly in the luxury vehicle, gambling and real estate sectors.

“We were getting too many (referrals from police) filed… that weren’t eligible and it was becoming overwhelming for the staff.”–Melinda Murray, executive director of forfeiture unit

Concerns were also raised that the existence of money laundering in B.C. could be partially responsible for the opioid epidemic. All told, more than 200 witnesses were called to testify before the commission’s final report was released in June 2022.

One of those witnesses was Melinda Murray, who said the experience with Manitoba’s Criminal Property Forfeiture Unit was that her office had traditionally received so many referrals for forfeiture from police that her staff couldn’t keep up.

“We were getting too many (referrals from police) filed… that weren’t eligible and it was becoming overwhelming for the staff,” Murray testified to the commission.

Justice Minister Kelvin Goertzen dismissed concerns the unit’s work could create a perverse incentive structure for law enforcement, and said he did not want to see a day where police were getting less of the civil forfeiture pie.

“I also think it is important that we provide significant funding to police agencies and police officers because ultimately they are responsible for preventing more victims from happening. The best investment you can have in a victim is to prevent one,” Goertzen said.

“That’s an important element of it and I don’t want to see that change. I don’t want to see funding initiatives for police officers being taken away. They’re the ones responsible for preventing more victims from being created.”

There have been many high-profile cases in Canada where it seems the original intent of civil forfeiture laws — to crack down upon and disrupt organized criminal networks — have been perverted to seek forfeiture for its own sake.

In B.C., luxury vehicles have been seized when drivers are caught speed racing on public roads.

In Saskatchewan, a man named David Mihalyko sold $60 worth of his prescription pills to an undercover police officer — reportedly to get gas money to drive to work — and as a result the province sought to seize his $7,500 truck as an “instrument of crime.”

In Ontario, Maggie and Terry Reilly owned several rental properties in Orillia, two of which had tenants who were accused of selling drugs. As a result, the Reilly’s properties were seized by the government in 2008, despite the fact they were never accused of a crime.

The Canadian Constitution Foundation took up the Reilly’s case in 2016, and in 2018, the Ontario government agreed to compensate them for the loss of their properties a decade prior.

In its 2016 review of civil forfeiture regimes in Canada, the CCF found that “no province has surveyed whether its forfeiture regime is meeting its statutory goals of deterring illegal acts and compensating victims.”

This is true in Manitoba, where no audit of the unit has ever been conducted.

JOHN WOODS / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS Justice Minister Kelvin Goertzen dismissed concerns the unit’s work could create a perverse incentive structure for law enforcement.

Goertzen concedes it’s difficult to track the impact of civil forfeiture on underlying crime rates — a point also made by academics who have studied the issue — but says that doesn’t mean it shouldn’t be vigorously pursued by the province.

“From a political perspective, I don’t look at whether it’s achieving x-amount of reduction in crime. I simply look at it as every dollar that is taken, is a dollar that’s going back into helping avoid another victim,” Goertzen said.

“It’s also sending a message that people who are committing crimes are not able to hold onto that wealth. I don’t look at it only as a return-on-investment perspective… but about what society demands.”

But a few cases in Manitoba have raised concerns among defence attorneys and academics about potential mission creep: where civil forfeiture has been used in situations where there were no allegations of profitable crime at all.

The first such case was against a man named Stephen Skavinsky, a Winnipeg soccer coach whose house was seized by the unit after he was accused of sexually assaulting a girl on his team. The argument was that the home served as an “instrument of crime” that facilitated his assaults.

“It’s also sending a message that people who are committing crimes are not able to hold onto that wealth. I don’t look at it only as a return-on-investment perspective… but about what society demands.”–Justice Minister Kelvin Goertzen

In her 2014 research paper, Michelle Gallant said that while the Skavinsky case appeared to be an aberration, there was nothing in the legislation that limited the unit to targeting “profitable crime.” She argued it would be important to track any future cases of a similar nature.

Gord Schumacher, then-director of the unit, said publicly that it was not the “intent” of the law to go after cases like the one involving Skavinsky, who later pleaded guilty to four sex charges involving the underage girl.

But fast forward to the present day and the unit is doing it again.

On May 19, the unit filed a Statement of Claim in Manitoba’s Court of King’s Bench seeking to seize the house of Kelsey McKay, the Winnipeg high school football coach accused of sexually abusing his players. He is currently facing at least 30 criminal charges.

And while people accused of sexually abusing children are not sympathetic in the eyes of the public, academics and lawyers have said the public should care about the precedents being established by these cases.

“There may be some reason to suspend concern about the incredible span of this power when the state is confronting organized crime. There may be some parity of arms between the state and organized crime. Perhaps powerful new tools are needed.”–Michelle Gallant, professor

In her 2014 research paper, Gallant said that while civil forfeiture regimes can be a valid tool used against organized crime, society must be careful to ensure that such a “vast extension of state power” is not ultimately misused or allowed to run off course.

“There may be some reason to suspend concern about the incredible span of this power when the state is confronting organized crime. There may be some parity of arms between the state and organized crime. Perhaps powerful new tools are needed,” Gallant wrote.

“But the alleged perpetrator of the assault is not that powerful entity. Rather, the enormous power of the state may be pitted against the powerless, the ill, the addicted, the socially excluded or the marginalized… In any event, to leave these concerns at the altar of judicial discretion may not be prudent strategy.”

Melinda Murray said the unit doesn’t take on cases involving non-profitable crime lightly, but said that sometimes the public interest demands it.

“There has to be a real and meaningful connection between the asset and the offence. It can’t just be that someone assaults a person in a house and so we’re going after the house. We don’t do that type of case, that’s not what we get involved with,” Murray said.

JOHN WOODS / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS Melinda Murray, director of the Manitoba Criminal Property Forfeiture Unit, stressed the unit doesn’t take on cases based on their profitability.

Murray also stressed the unit doesn’t take on cases based on their profitability. She pointed to the seizure of a former Hells Angels clubhouse in Winnipeg as a case where the unit lost money in legal fees, but felt the seizure was nevertheless in the public interest.

Jeffrey Simser is a leading expert on civil forfeiture in Canada, and a longtime lawyer with the attorney general in Ontario, though now retired. He said in his opinion, Manitoba has been quite judicious when it comes to how it uses its civil forfeiture regime.

“From my perspective — and yes, you can always improve things — but I think it’s an effective law, and I think Manitoba has used its law very effectively… It’s important to understand there are safeguards embedded throughout the legislation,” Simser said.

“The whole process was really built with profound — and I mean this really deeply — a profound respect for the rule of law.”

But Gowenlock questions whether the existing legislation has adequate safeguards in place.

“It’s an effective law, and I think Manitoba has used its law very effectively… It’s important to understand there are safeguards embedded throughout the legislation.”–Jeffrey Simser, civil forfeiture expert

In 2019, the unit successfully seized the North Kildonan home of Quang Nguyen, a first-time offender and a Vietnamese refugee who was sentenced to 15 months imprisonment after being caught running a marijuana grow operation.

Nguyen’s home, the site of the grow operation, was seized as an “instrument of crime,” resulting him losing about $100,000 of equity. This case resulted in the only trial in the history of Manitoba’s Criminal Property Forfeiture Unit.

Gowenlock represented Nguyen, all the way up to the Manitoba Court of Appeal, but they lost the case, with a judge ruling the seizure did not run “clearly contrary to the interests of justice,” despite the fact Nguyen wasn’t accused of buying his home or paying off his mortgage with money obtained through illicit means.

“They weren’t even alleging that his house was the proceeds of crime, but that it was an instrument of crime. I guess the thought being: by making someone homeless, we’re stopping him from doing another grow-op,” Gowenlock said.

“But to me, that’s seems a bit different than what people had in mind when they were thinking about taking away the tools of crime.”

In June 2022, the Cullen Commission released its final report, determining that B.C. was awash in money laundering, and among its recommendations, arguing the province needed to pursue civil forfeiture more aggressively.

These findings were, in part, used to back-up and justify the 2021 amendments to the Manitoba Criminal Forfeiture Act, which granted significant new powers to the unit.

The unit has traditionally been comprised of six full-time staff, including the executive director, and a student. Now that the unit is being expanded, it is in the process of hiring a financial analyst and two money laundering investigators, bringing its number of permanent employees to nine.

In March, the Winnipeg Police Service announced that it had seized roughly $160,000 in cash, as well as methamphetamine, fentanyl and cocaine with an estimated street value of $2 million, in a series of busts that, in part, resulted from tips from out-of-province law enforcement.

MIKAELA MACKENZIE / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS FILES WPS Insp. Elton Hall said a large drug bust in March was evidence that interprovincial organized crime groups were trying to infiltrate and take over Winnipeg’s drug market.

At a press conference, WPS Insp. Elton Hall said the busts were evidence that interprovincial organized crime groups were trying to infiltrate and take over Winnipeg’s drug market.

Gallant said there is reason to be worried civil forfeiture hasn’t been as effective at disrupting organized crime as initially hoped — and in particular, she points to B.C. as a “stunning” and somewhat ironic case study.

“B.C. vigorously pursued civil forfeiture for 10 to 15 years. And yet that massive study found that money laundering was rampant. All of these regimes were about confronting money laundering and the financial elements of crime. Civil forfeiture was an outgrowth of that,” she said.

“But that report is quite stark in its revelations of money laundering. And you’ve had this device all along. So maybe the device has been working, in the sense of bringing in all this money, but it hasn’t been working to stop the underlying crime.”

Gowenlock was more biting in his assessment, calling it an example of the government saying: “You’ve given us these authorities to stop this problem. The problem is growing. Therefore we need more authority.”

“Clearly there was a large increase in forfeitures last year. I can’t even speculate as to what is going on. It’s difficult to know… Is there more drug dealing going on? Did the pandemic have anything to do with it? Is it that police are doing more investigations and projects?”–Melinda Murray, executive director of forfeiture unit

For her part, Murray said it’s unclear what, precisely, is responsible for the record value of assets seized in 2021-22, and only time will tell if it’s an anomaly or the beginning of a new trend.

“Clearly there was a large increase in forfeitures last year. I can’t even speculate as to what is going on. It’s difficult to know… Is there more drug dealing going on? Did the pandemic have anything to do with it? Is it that police are doing more investigations and projects?” Murray said.

“I can’t guess. We get all our referrals from law enforcement.”

With the 2021 amendments to Manitoba’s legislation, the unit has now been granted considerable new powers.

One example relates to what are commonly called “unexplained wealth orders,” which use the courts to compel someone to reveal to authorities the source of their money or property, if the authorities have reason to suspect it is not lawful in origin.

As a result, the unit will now have the ability — on the basis of a “reasonable suspicion” on behalf of the executive director — to compel financial institutions to release records regarding their clients, and to refrain from notifying the client these records have been requested.

“It’s suspicion. That’s the basis. It’s a very loosey-goosey standard… One’s financial dealings, what one owns, their sources of income, is among the most sensitive information and one should have a significant expectation of privacy.”–Karl Gowenlock, criminal defence attorney

Critics have charged that the use of unexplained wealth orders have significant civil liberties implications — undermining the presumption of innocence, eroding privacy rights, and chipping away at protections from unreasonable search and seizure.

Those concerns are echoed by Gowenlock, who says he considers the 2021 legislative changes to be vulnerable to a constitutional challenge — one he hopes takes place sooner rather than later.

“Reasonable ground to suspect is the standard. It’s not reasonable ground to believe. It’s suspicion. That’s the basis. It’s a very loosey-goosey standard… One’s financial dealings, what one owns, their sources of income, is among the most sensitive information and one should have a significant expectation of privacy,” Gowenlock said.

“I think this is giving unchecked power to an agent of the state to snoop in people’s bank accounts on the basis of a suspicion. And I don’t think it’s hyperbole to say that.”

ryan.thorpe@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @rk_thorpe

Ryan Thorpe likes the pace of daily news, the feeling of a broadsheet in his hands and the stress of never-ending deadlines hanging over his head.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.