Shortages can’t curb electric vehicle enthusiasm Expect to wait a year or more to get behind the wheel of the EV of your dreams

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 09/12/2022 (1094 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

If she’s lucky, Connie Blixhavn will watch her husband drive his first fully electric truck by Christmas.

“We’re just crossing our fingers and hoping,” she said on a cold November day.

She couldn’t remember how long ago Bruce, her partner, had ordered his Ford F-150 Lightning — maybe it’s been a year, or eight months?

Blixhavn got her red Ford Mustang Mach-E in January of 2021 after waiting seven months, she said.

“We’re willing to wait,” Blixhavn said. “This is (the vehicles) we wanted.”

A two-year wait isn’t uncommon, said James Hart, president of the Manitoba Electric Vehicle Association.

He expects wait times to stay long for years.

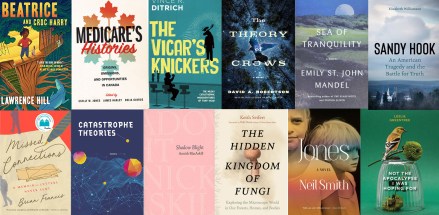

RUTH BONNEVILLE / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS Nott Autocorp will likely double its number of electric vehicles sold this year compared to last, said Trevor Nott.

“There doesn’t seem to be any relief in sight, from what I’m hearing,” noted Trevor Nott, president of Nott Autocorp. “The wait times, they keep getting pushed back and back.”

His lot contains new and used Teslas. Some electric and hybrid vehicles are “harder to locate,” and more costly, making the price of re-marketing higher, Nott said.

Even so, Nott Autocorp will likely double its number of electric vehicles sold this year compared to last, he said.

“The less expensive cars, the under $50,000, are still selling very well,” Nott said, adding rising interest rates have slowed the automobile market.

“There doesn’t seem to be any relief in sight, from what I’m hearing.”–Trevor Nott, president of Nott Autocorp

Manitoba is currently home to 1,858 electric vehicles and 11,484 hybrids, according to Manitoba Public Insurance data. Last year, the numbers were 1,080 and 9,480, respectively.

“It would… (be) higher if there wasn’t the chip shortage that is plaguing the auto industry,” said Robert Elms, the Manitoba Electric Vehicle Association’s former president.

Teslas accounted for 54 per cent of all electric vehicles in Manitoba last year, according to the association’s data.

“People have had the opportunity to start seeing more (electric vehicles) around,” Elms said. “It’s becoming a little less scary.”

JESSICA LEE / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS Former president of the Manitoba Electric Vehicle Association Robert Elms (right) and friend Lois Bergen with their Tesla at Assiniboine Park. There would be more EVs on the road in Manitoba ‘if there wasn’t the chip shortage.’

Higher gasoline prices and an increase in charging infrastructure is causing folks to convert, he added.

“If you can adjust (your) desire for certain (vehicle) options, then that might help you to get the vehicles a little sooner,” Elms said.

It’s what he did: he ordered a Tesla Model Y in May and kept asking for the vehicle. Last month, the company told him about a Model Y available in Saskatoon, he said.

This SUV is different — it’s a performance edition, with a slightly lower driving range and a white interior. The price tag was about $1,200 extra, Elms said.

He and his friend, who he’s splitting the vehicle and bill with, jumped on it. They have the ride now.

“The whole industry is backlogged.”–Sam Fioriani

He’s happy with his buy despite it not being his first choice, he added.

Supply chain issues — especially a shortage of semiconductor chips — remains the reason for a lack of cars, said Sam Fioriani, AutoForecast Solutions LLC’s vice-president of global vehicle forecasting.

“The whole industry is backlogged,” including gas powered vehicles, Fioriani noted.

Semiconductor chips are in almost anything electrically powered — from engine controls and transmission to navigation systems and steering wheels, Fioriani said.

“The tight supply of semiconductor chips… has caused vehicles to be partially built and parked until they get enough chips,” he said. “It’s caused plants to shut down.”

This has been a problem for two years, Fioriani said. During the pandemic, chip suppliers shifted their sales to electronics manufacturers — the auto industry had halted production.

Selling to electronics makers is more profitable. The chips are modern, and there’s a demand. Vehicles require older, more stable chips, Fioriani said.

“If you have a cellphone and the chip has a glitch, you just restart the phone,” he said. “If you’re driving along and the chip has a glitch, you can’t just stop in the middle of the interstate.”

New chip fabrication facilities are slowly coming online, and other supply chain knots, like a lack of shipping containers, are slowly being resolved. The auto industry is homing in on electric vehicles — Prime Minister Justin Trudeau announced Canada will ban sales of new fuel-burning cars beginning in 2035.

Still, “we’re probably looking at a new normal,” Fioriani said.

It takes time to open manufacturing plants, he said. Also, customers haven’t had much negotiating power.

“The auto industry over the last three years has realized they can make more money off of lower volumes,” Fioriani said. “We may not ever get back to the volumes we saw in 2019.”

But capitalism generally prevails, he added.

“Manufacturers will want to get one more vehicle than the next guy,” he said. “Dealers will want to sell one more vehicle than the dealer down the street.”

It’ll likely take at least two years for the auto industry to stabilize, Fioriani said.

Canada’s catch-up will take longer than the United States since it’s a smaller market, drawing less attention from manufacturers, Fioriani said.

gabrielle.piche@winnipegfreepress.com

Advocates push for more charging stations, subsidies

Gabby is a big fan of people, writing and learning. She graduated from Red River College’s Creative Communications program in the spring of 2020.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.