Clock is ticking for Theresa May

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 26/11/2018 (2570 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

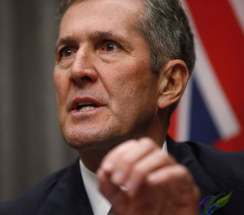

British Prime Minister Theresa May has given herself about two weeks to persuade her Parliament to accept the deal she made for divorcing the U.K. from the European Union. The vote is scheduled for Dec. 12, and if parties vote the way they’ve been talking, they’re going to turn it down.

It is already settled both in British statute law and in EU law that U.K. membership will cease at noon Brussels time next March 29. But what, then, happens to the rights of Europeans living in the U.K. and Britons living in Europe? What happens to U.K. and EU trawlers fishing in the shared coastal waters? What happens at the border between Ireland, which remains in the EU, and Northern Ireland, which leaves? What happens to U.K. immigration controls and to enforcement in the U.K. of decisions of the European Court of Justice?

These and a host of other loose ends are dealt with after a fashion in the 599-page divorce terms the EU heads of government quickly approved on Sunday. All the U.K. opposition parties and some of Mrs. May’s ruling Conservatives find much they dislike in the agreement. Mrs. May and European Commission head Jean-Claude Juncker have both said no other terms are possible, though they have no real way of knowing if that is true.

Parliament could refuse this agreement and make the country take its chances with what happens on March 29. That course would threaten four months of economic decline followed by many months of administrative chaos. Or Parliament could refuse this deal and send Mrs. May or another prime minister back to Brussels to demand different terms. British opinion, however, shows no consensus on what changes should be made or what sacrifices should be offered in return.

In the June 23, 2016, referendum, 52 per cent of U.K. voters said Leave and 48 per cent said Remain. Now that practical difficulties have appeared, the result might be different today. Some Remainers are therefore seeking a second referendum, now that the terms of the divorce are known. But Britain, Europe and the watching world have already organized themselves around the expectation of a smaller Europe, and a poorer and more isolated U.K. There seems no point in offering the public the choice of remaining in Europe. That ship has already sailed.

Canada’s interest is best served by a quick, smooth settlement of the points in dispute between London and Brussels so that industries can settle into a new set of rules and contribute to economic expansion. Canada already has a free trade agreement with the EU and could soon have one with the U.K. The longer Britain and Europe hover in fractious uncertainty about their relationship, the tougher it will be for Canadians to do business with them.

As the time for decision draws closer, the current war of nerves will probably grow more intense. Britain’s opposition parties are free to fantasize without limit about the better terms that might be available. Mrs. May’s Conservatives and her Unionist supporters from Northern Ireland, however, will have to consider what their own prospects will be if they pitch their country into deeper economic turmoil. She has two weeks to persuade them to swallow their principles and accept half a loaf.