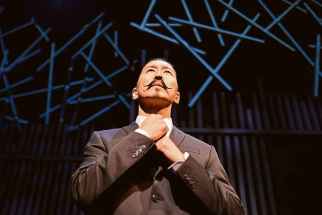

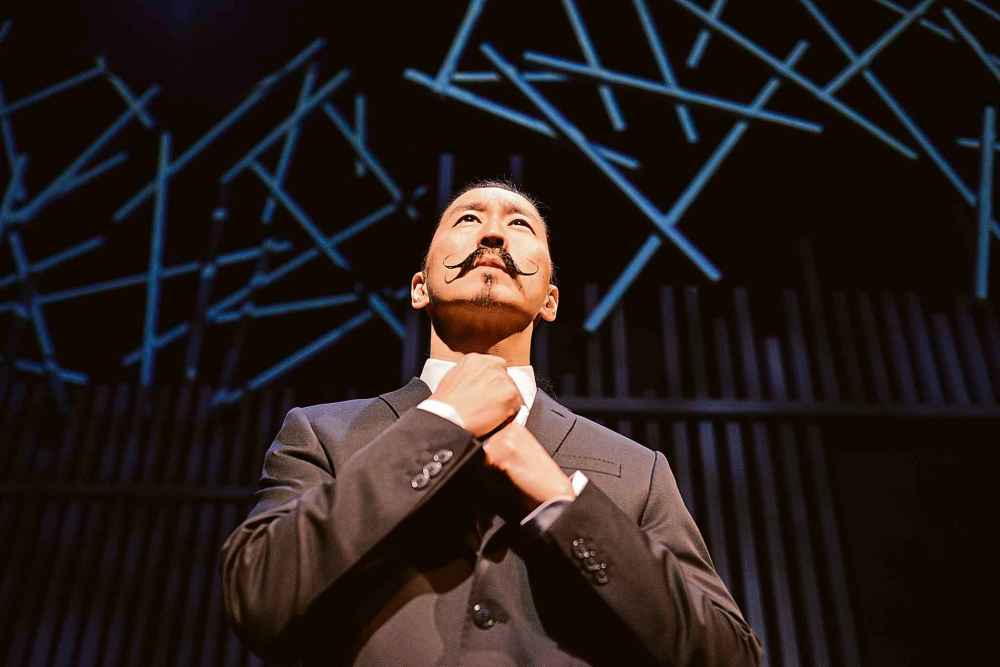

Lessons from his father Playwright's one-man show just one part of his diverse career

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 26/11/2018 (2663 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Reading Tetsuro Shigematsu’s resumé is apt to give you whiplash.

The London-born performer-playwright might be best known as the voice of CBC Radio One’s The Roundup, where in 2004, he became the first visible minority to host a daily national radio program in Canada. He’s studied with beat poet Allen Ginsberg in New York and Butoh dance guru Kazuo Ohno in Japan, starred in a TV movie with Star Trek’s George Takei and written for CBC’s This Hour Has 22 Minutes.

In what he calls “possibly the dumbest thing I’ve ever done,” he took part in the first season of the reality TV show The Deadliest Warrior (in case you’re wondering, a samurai would totally beat a Viking in a fight).

He’s a Vanier scholar, speaks English, French, Japanese and Persian, and wrote for the Huffington Post.

So, would the 47-year-old — who just defended his PhD thesis last month — classify himself as a Renaissance man or a perpetual student?

“I think I have a short attention span,” Shigematsu says from his home in Vancouver. “When something becomes uninteresting to me, I just move on. I think people were mystified when I left radio because in worldly terms, it was a desirable position. But I went in with very specific questions: a desire to understand sound; how information is processed by listeners in real time; interview skills.

“I felt that once my curiosity was satisfied — not that I’m claiming any level of mastery — but once something becomes routine or less risky, when I go into work saying, ‘I think I know what I’m doing,’ that for me is not a great feeling.

“There’s a great quote from (race-car driver) Mario Andretti that’s goes something like, ‘If everything feels like it’s under control then you’re probably not going fast enough.’ I’m most comfortable in the zone where I feel like I’m on the brink of failing.”

Having said that, Shigematsu admits that with Empire of the Son, he’s found himself settling into something of a familiar groove. He’s performed the autobiographical show about his relationship with his Japanese-born father more than 150 times; his current tour brings it to Prairie Theatre Exchange on Wednesday, kicking off the theatre’s Leap Series of three provocative, challenging one-person plays.

He calls the play’s success “a peculiar fate” — one that has afforded him the opportunity to tour his own work nationally and internationally, something many theatre artists would envy, but at the cost of having time to develop new projects.

“I remember being at the PNE (Pacific National Exhibition in Vancouver) and seeing Boy George and these other acts from my youth performing their hit songs ad infinitum — and I wondered what kind of fate that would be,” the playwright says. “I had a brief thought experiment: if the devil ever came to me and offered me the chance to be a rock star, but the cost would be I had to play the same damn song forever, would I take that deal? I thought, yeah, I would, because that’s not such a big price to pay.”

However, revisiting a fraught, emotionally volatile relationship onstage is not the same as singing Karma Chameleon every night; it’s likely more draining, and more rewarding. Shigematsu says if it weren’t gratifying for both the artist and the audience, it would be “a kind of purgatory,” but the play hasn’t stopped paying emotional dividends.

“I’ve come to see it as a kind of spell that I recite before a group of people and the magic isn’t necessarily what I’m experiencing, although that can happen, but the effect that it has on the audience,” he says. “I always talk to people afterwards and I hear extraordinary stories from people that are not inclined to share something personal.”

Empire of the Son stirs up emotions because it’s at once deeply personal and universal. It’s the story of growing up with a remote, taciturn father, also a radio broadcaster, who showed his son little affection and never cried.

After his father became ill, Shigematsu worried his own children would never know anything about their grandfather’s life. He appealed to his father’s broadcast personality to break the silence between them, conducting two years’ worth of interviews. Some of the recordings are used in Empire of the Son, a multimedia show the playwright says is more performance art than traditional theatre.

Theatre preview

Before his father died, the playwright asked his permission to write a play based on the interviews. It was a necessary step, not only for Shigematsu’s conscience, but because his father was more than an artistic inspiration. He was a live research subject for the author’s proposed dissertation, Empire of the Son: Using Research-Based Theatre to Explore Family Relationships; if he declined, not only would there have been no play, but Shigematsu’s PhD would have been in peril.

His father had not approved of his earlier autobiographical work, Rising Son, telling people, “My son makes fun of my accent for a living,” but to Shigematsu’s surprise, he agreed.

“His health was at a point where he would take sometimes two minutes to answer a question,” Shigematsu recalls. “But immediately he said, ‘Yes!’ I thought, ‘Maybe the dementia’s set in,’ maybe he thought I was offering him 7-Up, which was his favourite beverage. I had my mother ask him in Japanese and again he said, ‘Yes!’”

When Shigematsu asked him why he’d had a change of heart, he replied, “Because if you tell my story, then my life will have had some meaning.”

The elder Shigematsu died just weeks before his son debuted the show in 2015, which obviously made for an emotional opening run. But even years later, even though the play is full of laughter, the performer says he struggles against tears some nights.

“I explain to the audience that I haven’t cried since I was a kid, I didn’t cry when my father died, and so tonight… maybe together, if you open yourself to me and I open myself to you, we might be able to break up the ice that’s around my heart and I might be able to feel something. That’s actually the honest task that I set myself every night,” the performer says, adding that he is not a trained actor.

“The paradox that continues to puzzle me is that the more I perform this show, the more emotional it becomes, despite the fact that temporally, the incident of my father dying is further and further away.”

jill.wilson@freepress.mb.ca Twitter: @dedaumier

Jill Wilson is the editor of the Arts & Life section. A born and bred Winnipegger, she graduated from the University of Winnipeg and worked at Stylus magazine, the Winnipeg Sun and Uptown before joining the Free Press in 2003. Read more about Jill.

Jill oversees the team that publishes news and analysis about art, entertainment and culture in Manitoba. It’s part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.