Police chief Danny Smyth can help stop the bleeding

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 26/11/2018 (2663 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

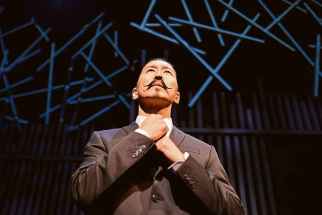

Danny Smyth was one of two police officers first on the scene after J.J. Harper was shot by Const. Robert Cross in March 1988.

While fairly new to the Winnipeg Police Service, Smyth covered and held Harper’s wound, accompanying him in the ambulance to hospital.

He also, like the rest of Winnipeg, witnessed then-chief Herb Stephen exonerating Cross of any wrongdoing. Smyth — while likely aware of a cover-up among officers — later testified during the following Aboriginal Justice Inquiry, providing evidence that disputed the claim the shooting was accidental.

According to then-Winnipeg Free Press columnist Gordon Sinclair Jr., Smyth — now the WPS chief — was the “one cop who seemed to have done the right thing.”

The public outcry from the Harper shooting, the recommendations of the inquiry, and later commissions (such as the Taman Inquiry) led to changes in the way investigations of police are handled. This resulted in the formation of the Independent Investigation Unit of Manitoba in 2015, a body headed by former Crown prosecutor Zane Tessler and “mandated to conduct transparent and independent investigations of all serious incidents involving police.”

During an eight-month investigation led by investigative reporter Ryan Thorpe, the Free Press learned the IIU has fallen short as an oversight body, particularly over the WPS.

The IIU has had its work resisted, obstructed, and undermined by the city police. At the same time, it’s been exposed that the IIU has no teeth (with officers openly refusing to participate), is not as “civilian-led” as it poses to be (made up mostly of ex-police officers), and is mired in a jurisdictional power struggle with the WPS.

This has raised an aura of suspicion surrounding possible cover-ups, problems with police investigating police, and injustice at all levels.

Sound familiar? It feels like 1988 all over again.

Smyth’s career, it appears, has come full circle.

Armed with the recent revelations surrounding the IIU, lawmakers have to act. My Free Press colleague, Dan Lett, wrote Monday the “ball is now squarely in Justice Minister Cliff Cullen’s court.”

I agree. Lawmakers have to intervene and the province — which mandates and oversees the IIU — must act swiftly and determinedly.

Public confidence is shaken in the IIU and the WPS — and deservedly so. It’s traumatic to find out that public institutions are nepotistic, corrupt, and act nefariously, especially when those institutions purport to deliver the law.

So, welcome to Indigenous life.

Indigenous peoples are the most over-policed people in Canada. This has a lot to do with policies and practices that have targeted our community, driven, and kept us in the throes of poverty.

I feel bad sometimes for police officers, who have often been the primary deliverers of Canada’s aggressive attacks on Indigenous communities. Some didn’t choose this role, but all police inherit it.

It’s also difficult to understand the complexities of 150 years. Police officers often have to respond in seconds to situations and conflicts that took a century to develop. I wonder sometimes if police are adequately trained and supported to understand what they see — or unlearn what they’ve been taught.

At the same time, the track record of Indigenous peoples and the police is, in a word, brutal. Take, for example, the recent CBC report in April which stated the vast majority of those killed in incidents with police were Indigenous. Some were innocent, like J.J. Harper and 18-year-old Matthew Dumas, shot and killed by Winnipeg police on Jan. 31, 2005.

Indigenous women have perhaps bore the worst brunt of police violence.

…there must be Indigenous voices on the IIU, if for no reason than the vast majority of cases– and issues — comes from interactions between Indigenous peoples and the police

M’ikmaq lawyer Pam Palmater has been a leading voice, writing: “Evidence of the widespread nature of police violence against women in general is staggering… We have a rampant and systemic problem within Canada’s law enforcement that operates with drastically insufficient oversight and accountability.”

Indigenous peoples have long-standing and well-deserved suspicions of police, and the recent revelations surrounding the IIU do nothing but add to this.

What comes next now means everything to the Indigenous community — particularly since the majority of cases dealt with by the WPS are with Indigenous peoples.

The solutions seem so simple.

Police have to have objective, fair, and honest oversight — the kind judges and lawyers have. People in these professions have citizens from outside their communities assess their work.

Police should also not take the lead in overseeing police, even if retired. Here’s an idea: the IIU can employ ex-police officers, but they cannot be the majority.

Oversight bodies for police must have legislative and legal authority. Police participation in investigations must be led by the IIU. Witnesses must be called and come forward, even if they are police cadets, administrators, and “civilian staff.” The IIU must be allowed to collect whatever evidence it needs, without obstruction.

This all provides evidence why a civilian-led body intended to reflect the values and makeup of the community must actually represent it. That means there must be Indigenous voices on the IIU, if for no reason than the vast majority of cases — and issues — comes from interactions between Indigenous peoples and the police.

This all seems simple. Like doing the right thing. And, while provincial lawmakers should take a lead, who should actually do this?

Winnipeg Police Service Chief Danny Smyth.

I have to admit I was disappointed this past week, when I read a WPS internal memo written by Smyth, where he took issue with Thorpe and the Free Press.

He called the investigative reports on the IIU “long-winded editorials rather than serious investigative reporting.” Then, he spent two pages defending police accountability while admitting there are “gaps in the Police Service Act that require amendments.”

Police Chief Danny Smyth’s memo to officers

It was an odd response, as no one else in Winnipeg thought the IIU revelations weren’t legitimate.

Pretending there isn’t a problem in the WPS isn’t a good look. It sounds like an exoneration.

That’s not the Danny Smyth of 1988.

niigaan.sinclair@freepress.mb.ca

Niigaan Sinclair is Anishinaabe and is a columnist at the Winnipeg Free Press.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Tuesday, November 27, 2018 10:27 AM CST: fixes typo

Updated on Tuesday, November 27, 2018 1:53 PM CST: fixes word tense