The (railway) ties that bind The porter, a job born out of the end of slavery, helped build Winnipeg's Black community

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 11/06/2021 (1641 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

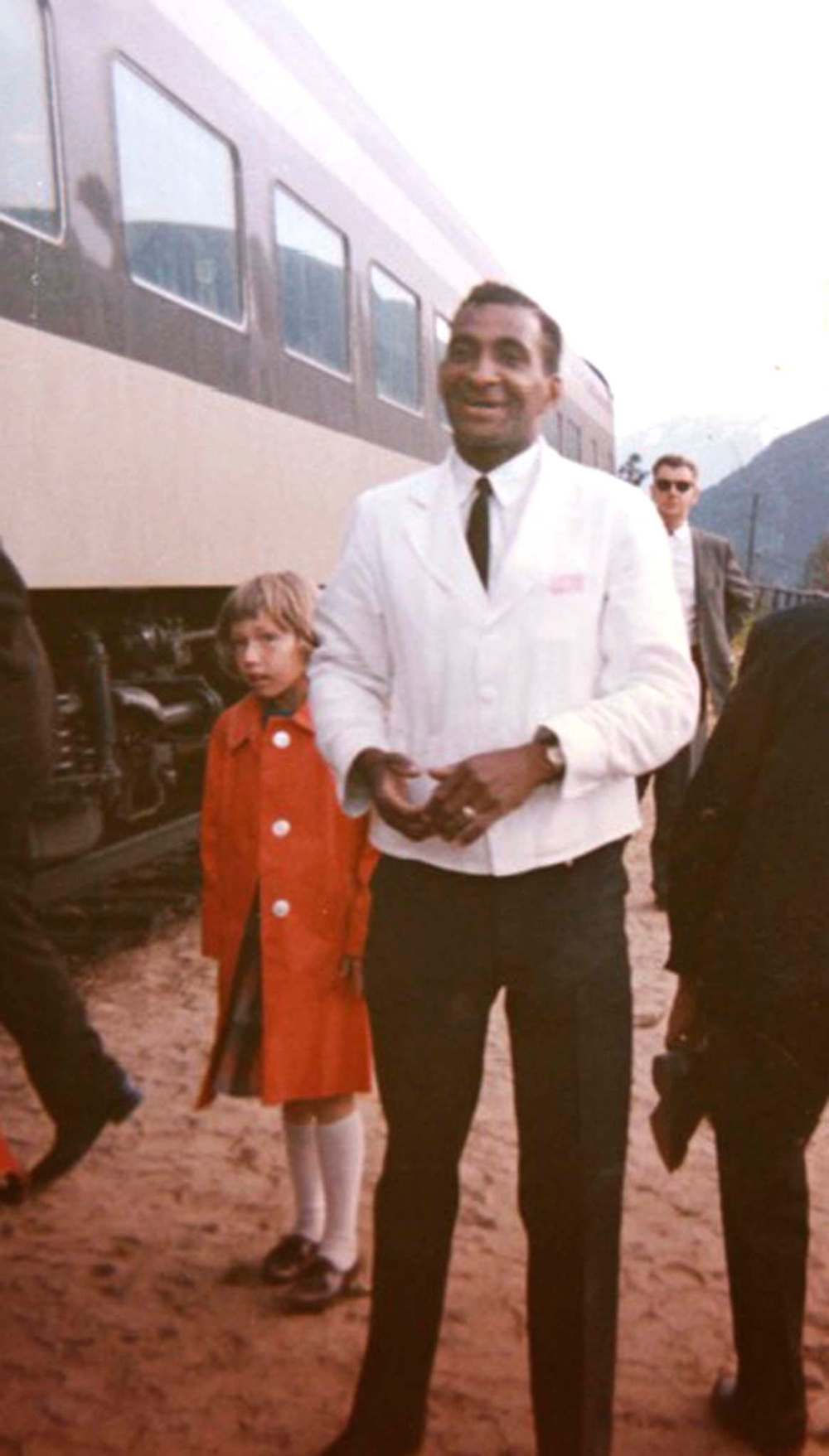

Five days after graduating from high school in 1972, 18-year-old Bob McDaniels boarded his first train and embarked on a career that would carry him to new cities, friendships and family.

McDaniels’ mother had encouraged him to follow in his late father’s footsteps by taking a job at CN Rail as soon as he was eligible. On that summer day, McDaniels boarded a line from his hometown of Winnipeg to Montreal, working as the train’s “pantry boy,” a dishwasher in the dining car.

“I never called it a job. I always called it a lifestyle as a railroader,” says McDaniels, now 67.

He would go on to spend his whole career working at what would become Via Rail. During his career, McDaniels met countless Black elders, many of whom had established lives in Winnipeg after finding steady — albeit challenging — work as sleeping car porters on the rails, and was warmly embraced by the unique community of the railroading crew.

Next stop: your TV

The eight-episode CBC drama The Porter will tell the story of Canada’s Black sleeping car porters, offering historical insights to the job that paved the way for Black community life in Canada’s western provinces.

Next February, the biggest Black-led production ever in Canada will bring an integral story of Winnipeg’s Black history to life — and to the screens.

The eight-episode CBC drama The Porter will tell the story of Canada’s Black sleeping car porters, offering historical insights to the job that paved the way for Black community life in Canada’s western provinces.

Though the show is set in Montreal, the story of the porters is at its heart a Winnipeg story. It was in this city’s northern neighbourhoods that North America’s first Black railway union was born, ushering in better work conditions for the city’s Black residents.

Porters became the bedrock of Winnipeg’s Black community, too, as Black men moved their families westward and settled in neighbourhoods and community hubs a stone’s throw from the old train station.

Though the porters stories are riddled with hardships, exposing at times the dark underbelly of Canada’s history, they are predominantly scored by resilience, friendship, and lasting family ties.

As a young and self-described “punk,” McDaniels said the train presented a host of learning opportunities as he worked his way up through the ranks. By the time he retired more than 35 years later, he had landed the prestigious service manager position, only made available to Black employees thanks to the work of Black Winnipeg porters before him.

“Anything I learned through that point in my life was by the train, through instructors or senior people who showed me how to do the job. They were my teachers,” McDaniels says.

The rail lines have long been an essential part of the McDaniels’ family storylines. McDaniels’ adopted father August, known affectionately among his fellow railroaders as ‘Book Off’ McDaniels, had begun working as a porter in the 1930s, and remained there until dying of cancer when Bob was just 13.

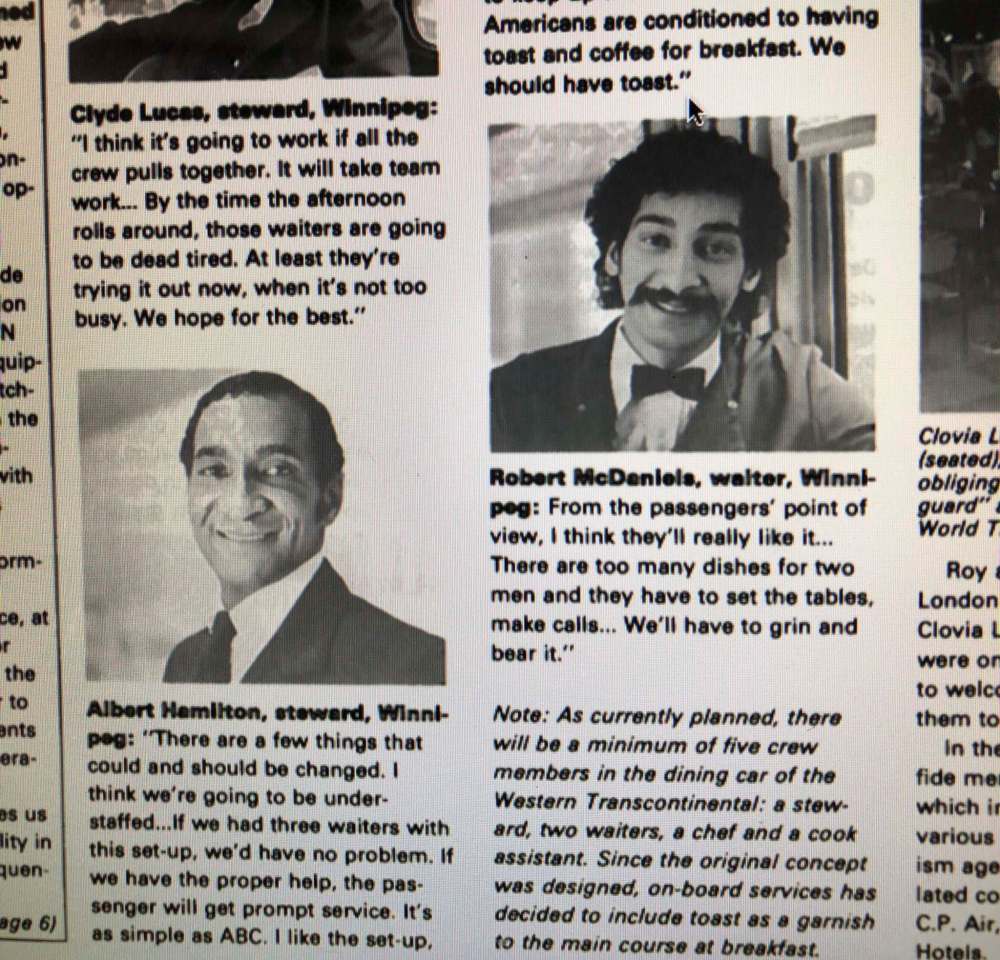

Years after his own retirement (when adoption records were opened in 2015) Bob McDaniels would also learn his biological father, Albert Hamilton, had been one of his co-workers on the railway line.

McDaniels met his wife, Brigite, on the trains, too. She was another porter, based out of Ontario, who he met at a conference. The two worked on the lines — sometimes from thousands of kilometres apart — until they had their first child together and his wife chose to stay home.

As a second-generation railroader, McDaniels was taken under the wing of the largely Black group of senior porters — many of whom had worked with his father through the 1930s.

“The older Black guys, they liked me because they loved my dad, so they instinctively tucked me under and showed me the ropes,” he says fondly.

“They always treated me like a million bucks, I always felt so special in their company.”

When he started in 1972, McDaniels was a grunt in the dining car, washing dishes and working to impress his superiors.

“I was always inspired to do the best job I could,” he says, adding employees on the CNR and CPR lines had to work their way up to secure better roles.

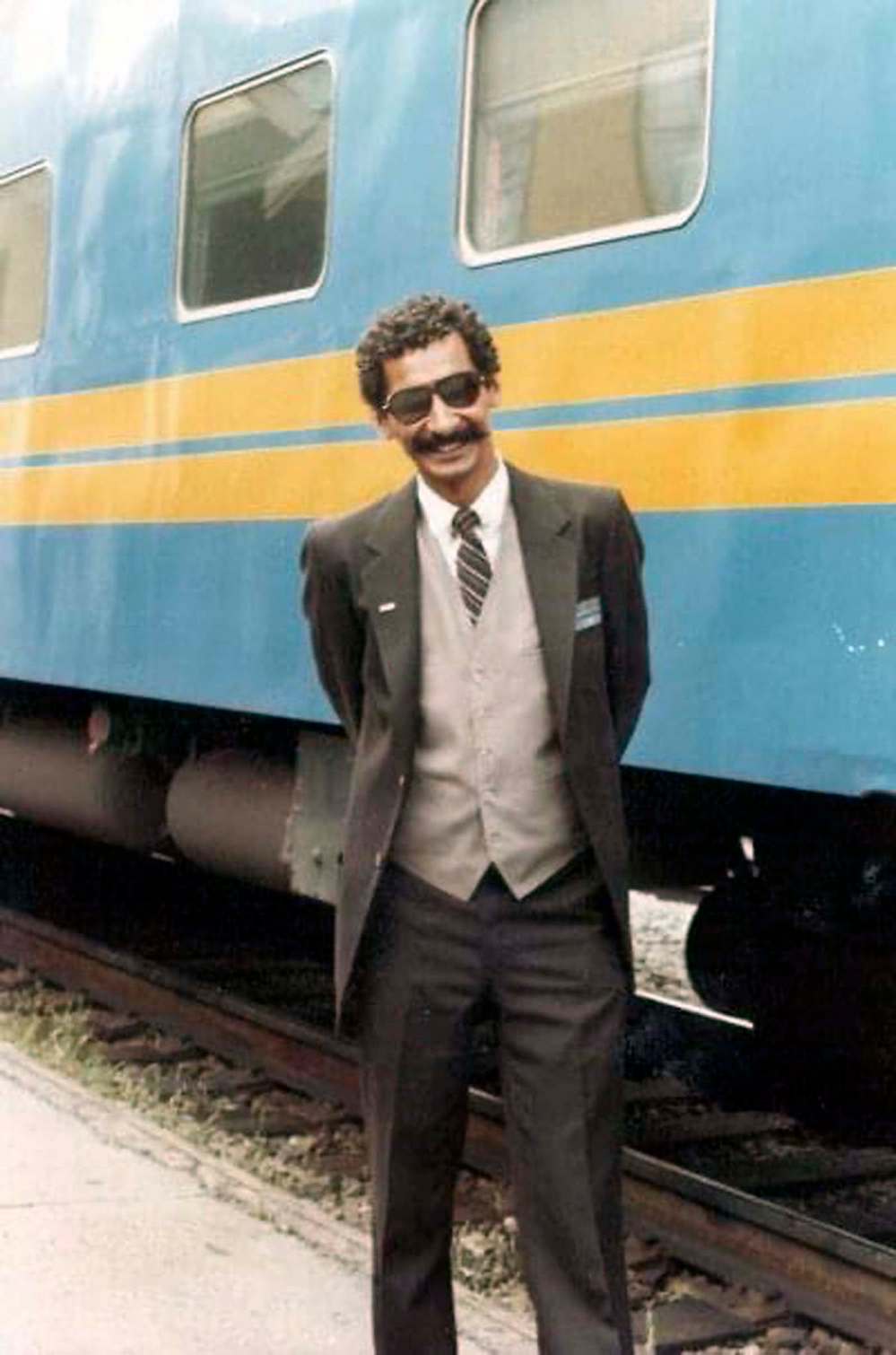

Just two years later McDaniels began working as a porter, though he would occasionally return to the dining car as a lead chef. By the end of his career he had worked nearly every job available on the train, including supervisory roles.

A sleeping car porter’s main responsibility is to look after the customers. Greeting them, orienting them to the train, explaining how things work in the rooms, taking care of baggage, cleaning and attending to customer needs were all part of a regular day’s work.

Shifts on the train were long and gruelling. Porters often worked for 72 hours one direction, spend a layover away from home, and work another 72 hours on the return trip in six or seven day stretches.

In the early days, McDaniels said porters like him worked 21 hours a day, resting for three hours in a “little roomette” on the train. While the money was good — complete with tips — the job could be exhausting.

Raising a family was difficult, McDaniels says, as busy schedules sometimes meant being away for holidays and birthdays. On one occasion he remembers spending Christmas in a small town and calling home to talk to his then three-year-old daughter, Julia-Faye.

“She’s sobbing on the other end of the phone, she can barely say anything. I’m crying on one end, she’s crying on another,” he remembers. “I said at that point, I will never miss another Christmas.”

From that year on, any Christmas he had to spend on the train, he would bring his wife and daughter along — a practice that wasn’t uncommon for porters, who took to one another like family.

“Lots of people did that because we all missed them. If someone brought their family on, they were our family too. We always took care of them — always.”

● ● ●

Marring the good times on the trains was a deeply rooted streak of discriminatory treatment. It had dwindled significantly by McDaniels’ days, but had run rampant among his father’s generation.

The McDaniels family immigrated to Canada from a small coal town in Indiana in the early 1930s, and the elder McDaniels quickly started work as a shoe-shiner, then on the railway, basing themselves in Winnipeg.

“Working on the railway …as a Black man starting out in the 30s there were a lot of things in front of him to stop promotions or wage increases. Your own peace of mind couldn’t be had because you were structured by sort of a racist system,” he says.

Certain passengers treated porters — especially Black employees — with a sort of arrogance, McDaniels says, remembering one passenger who insisted on calling him ‘boy’ during his time on the train.

“You can’t take your frustrations out on the passenger,” he says. “You have to really guard your words carefully when you’re in those situations.”

“As a black man coming to Canada [my father’s] first job is shining shoes, and here I am 50 years later and I’m required to shine somebody’s shoes? I said it was demoralizing– and they understood that.” — Bob McDaniels

He recalls a time when he was 21 and a man younger than him boarded the train in ‘civil war boots,’ fresh out of a farm field. The passenger placed his dirty boots in the shoe-shining box — a compartment in each room that could be opened from either side — expecting McDaniels to scrub them clean.

“I refused to shine shoes. That was a big part of the job and I just couldn’t do it. It was beneath me, so to speak, to do that,” he says.

Shoe shining was, at the time, mandatory for the sleeping car porters, but McDaniels said he took a stand because of his father’s history.

“As a black man coming to Canada your first job is shining shoes, and here I am 50 years later and I’m required to shine somebody’s shoes? I said it was demoralizing — and they understood that,” he says.

Shortly after the incident, McDaniels says the rail line stopped mandating the shoe shining aspect of the job, and the rest of his career was largely unmarred by the discrimination that had stained the career in decades past.

● ● ●

It was a presumed acquiescence to discriminatory treatment that made Black men the top choice for rail companies when the porter jobs began at the turn of the 20th century.

“When slavery ended in the United States and railway travel — especially luxury railway travel — was taking off, George Pullman, the creator of the sleeping car service, wanted to say to wealthy white people: All is not over. The world doesn’t come to an end just because you can’t have slaves anymore. You can still have the fantasy of having a servile Black person at your beck and call on my railway service,” explains Sarah Jane (Saje) Mathieu, a professor in the History department at the University of Minnesota.

“In order for Canadian companies to compete, they started building a sleeping car service and they to want to ensure that they could provide that racialist fantasy even though that wasn’t Canada’s particular path.”

The Pullman cars launched in Canada in the 1870s, and with them came the servitude model that distinguished the Pullman brand.

“If you were a Black man who went to McGill or you grew up in Winnipeg and you just didn’t sound sufficiently servile, you couldn’t get a job.”– Sarah Jane (Saje) Mathieu

American companies leasing or selling the sleeping cars to CPR and CNR railways secured the model of servitude in the contract — to buy a car you also needed 12 pillows and two Black people, Mathieu says.

“Canadian companies decided by the turn of the 20th century that they had to step take one step further and that was that they had to get the most seemingly authentic, servile black person. They would dip into the deepest part of the American south to find Black people with a southern accent to have white Canadians marvel at how the Canadian company was as good as the American one.

“In other words, if you were a Black man who went to McGill or you grew up in Winnipeg and you just didn’t sound sufficiently servile, you couldn’t get a job. Black men would affect the southern accent and probably cooked up all kinds of fantasy background for themselves in order to secure a job. Imagine the deeply disturbing racialist circle there.”

By 1909 there were dozens of Black men working as porters in Winnipeg. Some had moved up from the States, while others moved west from Halifax, Montreal and Toronto, where Black communities had already been established.

Mathieu based her book North of the Color Line: Migration and Black Resistance in Canada, 1870-1955 on research she did while writing her masters thesis, which focused on Black migration into Manitoba and the Canadian west. Through her research she found many Black communities had settled in Winnipeg, Calgary and other large cities across the west.

“I wanted to know what happened to them. I kept finding them on the rails,” she says.

“And so this young 23-year-old hitchhiked across Canada and parts of the U.S. looking for porters. I found most of them in Winnipeg.”

● ● ●

For the early Black community in Winnipeg, the porter job came with status; it provided secure income and respectable work, allowing Black men to plant roots for their families in a new town.

As Valerie Williams — daughter of the late Deacon, community leader and railroader Lee Williams — puts it: “there wouldn’t be a Black community without the porters.”

Early in the 20th century, Winnipeg was home to just a smattering of Black residents, many of whom had immigrated north after the emancipation of slavery in the southern United States.

The vast majority of Black men in Winnipeg, Williams recalls, were porters, establishing the beginnings of Winnipeg’s Black community in the shadow of the CPR railway station in what is now North Point Douglas.

“They were central to the Black community,” Williams says of the porters in a phone interview. “I think it would be safe to say the way the Black community evolved was through the porters.”

The Williams family had moved to a homestead in Saskatchewan in the early 1900s, arriving in 1910. Decades later, as a young adult, Valerie’s father Lee moved eastward to Winnipeg for a job as a porter on the CNR railway.

He would work on the rails for 42 years — retiring the very same year the young McDaniels would take his first train — and over that time Lee Williams would transform the working conditions for Black porters.

Lee Williams did not love his job on the trains, his daughter says — it was rife at the time with discrimination, racism and poor treatment — but it was secure income, with a solid pension that could support his growing family.

“He was committed, he was dedicated and he supported his family, did he enjoy the job? I think it was better when he was able to secure promotions and cross that hurdle of discrimination,” she explains.

“He led the fight for better treatment. He knew it was wrong, he knew they deserved equal rights.”

In 1955, Lee Williams challenged the predominant porter union at the time — the Canadian Brotherhood of Railway Employees — with a request to remove job discrimination from the union’s collective agreement, and thereby open room for Black men to be promoted on the trains. He was ultimately shut down.

Still Williams persisted. Along his many trips on the train, Williams had met and befriended a young Member of Parliament from Saskatchewan; a man who would later rise in political ranks to become Prime Minister John Diefenbaker.

As the story goes, Williams wrote to Diefenbaker once he was prime minister, asking for help securing better rights for the porters. Diefenbaker sent him a copy of the nation’s Fair Employment Practices Act, leading Williams to charge the rail companies with discrimination. Again, nothing changed.

A decade later, under then Liberal Prime Minister Lester Pearson, Williams tried again, demanding the act be enforced on the federal railways and Pearson backed him up, ordering the rail lines to comply. By 1964 many of the provisions that prevented porters from advancing in the CNR ranks had been eliminated.

For his efforts, Williams became the first Black porter to be promoted to sleeping car conductor and supervisory roles on the trains.

● ● ●

Mark Collins, 61, now a boxing instructor in Winnipeg’s North End, spent many years as a railroader too, joining the CN rail lines in 1979 and rising from dining car attendant to porter. The hours were long and the job was difficult, he recalls, but the money was steady, the job was known to hire Black people, and it opened doors to new opportunities.

“I don’t miss the job, but I miss the people and I miss the travelling,” Collins says in a phone call. “It was like a family.”

He got used to the schedule, he says, and enjoyed the long stretches of time off he could have in a single month — despite the busy days of work that would precede it.

Of course, even in his days, passengers on the railway could be ignorant.

“Ignorance is ignorance. I was subjected to that,” Collins says. “Unfortunately you’re in a position where, you know, I’m at work, so you get used to just absorbing it. All you can really do is just pray for people like that.”

But Collins remembers being mentored by the older Black porters who he worked with. At the time, his supervisor was Black too, and would coach him through the job.

“It was very rewarding because there was a lot of the classic guys that aren’t alive anymore who did that job right from the very beginning,” Collins says, adding they taught him little bits about the history of the rail lines.

● ● ●

Without Williams’ efforts, McDaniels acknowledges things may have been different for him on the rails.

The old guard on the trains usually kept quiet about discrimination they had faced, he says. His dad never mentioned any difficult experiences, though he heard whispers of the struggles the older Black employees had navigated.

“It was kind of hidden. My dad never said any stories and the older guys… never really told me much about what it was like to be a Black porter in the early 30s,” he says.

“No one really said too much but you could feel it. You could tell. A lot of those older guys, you could see it in the lines on their face some of the things they must have gone through — it tells the story without having to say it in words.”

Now 13 years into his retirement, McDaniels looks back fondly on his railroading job.

“To this day I have numerous amount of friends on there — and the friends become family,” he says, calling from his country home near Oak Point, Man.

Despite the gruelling hours and the occasional disrespect from customers, McDaniels said the people and the travel made the job hard to walk away from. The trains would trek up north to Churchill, or west to the Pacific shorelines of Vancouver, or east into Toronto and Montreal.

Between rigorous shifts, the porters would spend layovers in different cities, enjoying the landscape and each other’s company. On the trains they would have the opportunity to meet people from “all walks of life,” people who would become lifelong friends, or just appear for short periods of time.

“I think the camaraderie was one of the best parts of the job. To this day most of my friends are via rail people,” he says. “It was a regular melting pot working on the railway, and that was the best part in my opinion.”

julia-simone.rutgers@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @jsrutgers

Julia-Simone Rutgers is a climate reporter with a focus on environmental issues in Manitoba. Her position is part of a three-year partnership between the Winnipeg Free Press and The Narwhal, funded by the Winnipeg Foundation.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.