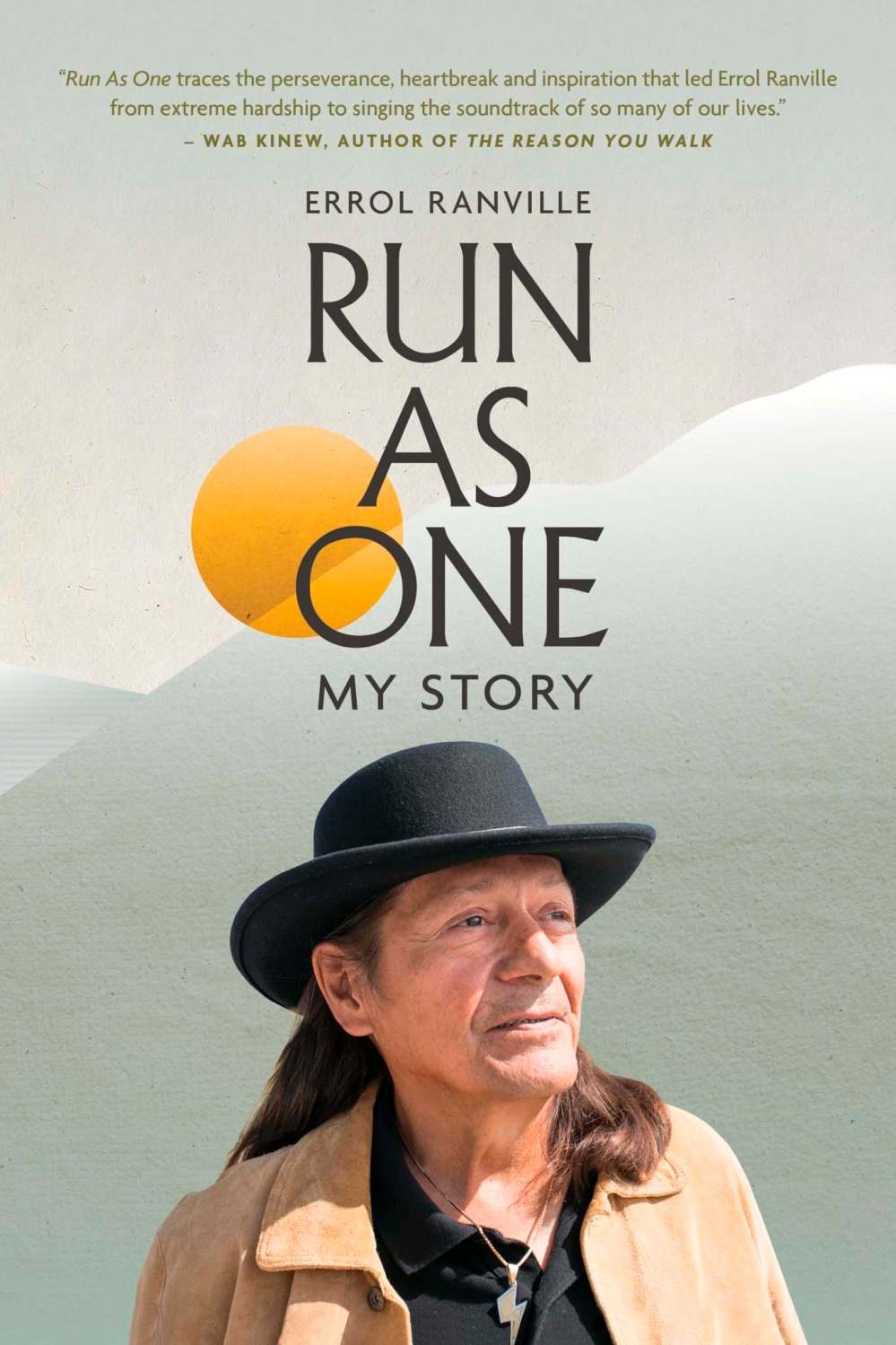

Seizing the day Local singer-songwriter Errol Ranville looks for ways to honour history while building bridges

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 11/06/2021 (1641 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Amid the shock and sadness, Errol Ranville sees an opportunity.

The discovery of the remains of 215 children at a former residential school in Kamloops, B.C., gives Indigenous artists like himself a chance to keep the memories of those who survived the schools’ abuse and the thousands who died at the schools at the forefront of Canadians’ minds.

“There’s a window right now for us. We’ve got the world’s attention and I think right now anybody of any prominence in what I call the Neeche community, this is our moment in time to address what happened and what it’s like today and (ask) ‘Where do we go from here?’” Ranville says.

“With all this about residential schools in the news cycle right now, you get emotional, and that’s when I write songs. Some of the stuff is hard to write about.

“How can we be able to participate in mainstream society? Where do we sit, now that the door is kicked open, so to speak? It’s unfortunate it had to be a situation like this, 215 children, but if that’s what it takes to get the general public’s attention…”

Ranville, 68, grew up near Eddystone, about 250 kilometres northwest of Winnipeg near the western shore of Lake Manitoba, and has finished a memoir that will detail his childhood years, growing up in poverty and learning how to play on a beat-up guitar with only five strings.

Ranville and his brothers Wally, Don, Bryan and Stirling would eventually form the C-Weed Band, which rose from Interlake bars and First Nation community halls to a band that earned two Juno Award nominations on the strength of songs such as Evangeline and Run as One, which will be the title of Ranville’s autobiography.

Ranville didn’t attend a residential school because he says his family had no treaty status, so the federal government didn’t notice him. He wound up going to schools in and around Eddystone until his family moved to Winnipeg so he could chase his musical dreams.

He says he’s one of the lucky ones. His older brother Stirling was sent to a residential school and Errol believes Stirling’s treatment there led to his addiction and mental-health challenges.

“I saw the trouble he had, adjusting to life in his early 20s, and his alcoholism and how it terrorized him,” Errol says. “Thank God all of us got sober. I’m going to 33 years of being clean and sober and he’s not very far behind.

“Had I been affected like he was, there’s no way I’d be where I am today. Absolutely no doubt in my mind.”

Among the many famous artists Ranville has crossed paths with during his music career include folk singer Buffy Sainte-Marie, who was born on the Piapot reserve in Saskatchewan. She became a trailblazer for Indigenous artists during the 1960s folk boom and continues recording and performing.

Sainte-Marie, 80, made a heartfelt treaty-land acknowledgement statement during the Juno Awards telecast on June 6, and the 215 children who were buried at the Kamloops gravesite were on many minds during the event.

“The recent discovery of even more remains of residential school Indigenous children, this time in Kamloops, it’s shocking to some people and a revelation, but it’s not news to Indigenous people,” Sainte-Marie said. “The genocide basic to this country’s birth is ongoing and we need to face it together, and I ask you for your compassion.”

The Tragically Hip’s appearance on the Juno telecast on Sunday — it was the Ontario band’s first showing onstage since the 2017 death of frontman Gord Downie — added a chance for viewers to reflect on Downie’s work to add visibility to Canada’s residential school history.

Downie was famous for writing songs about Canadian history, and in 2016 he released a solo album, The Secret Path, which was inspired by Chanie Wenjack, an Indigenous boy who died in 1966 while fleeing from the Cecilia Jeffrey Indian Residential School in Kenora, Ont., in an attempt to find his way home.

Downie’s album was accompanied by a graphic novel by Jeff Lemire and the two projects led to an animated TV film about Wenjack’s story.

In a statement Downie wrote in 2016 that is posted on The Secret Path’s official website, he says “white Canada” wasn’t taught about residential schools but would soon learn the grim details of an ugly part of Canadian history.

“The next hundred years are going to be painful as we come to know Chanie Wenjack and thousands like him — as we find out about ourselves, about all of us — but only when we do can we truly call ourselves, ‘Canada,’ “ Downie wrote.

Ranville believes Canadians are finally learning about the residential schools and the century-long history of abuse that took place. It gives him hope about the future relationship between Indigenous people and the descendents of settlers.

“I live here in Windsor Park and right across the street from me is a white family; they have ‘215’ in their front window, big, huge numbers, and it chokes me up,” he says. “With the first day I opened the curtains and I looked at that, I thought, ‘Holy man!’

“I think we all just have to walk out hand in hand and create the best of it. I think it’s important that we ourselves embrace the moment and be ready to make a better world.”

alan.small@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter:@AlanDSmall

Alan Small has been a journalist at the Free Press for more than 22 years in a variety of roles, the latest being a reporter in the Arts and Life section.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.