Monuments and meaning When we acknowledge the crimes of colonialism, we're learning history, not erasing it

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 11/06/2021 (1642 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

The first mistake is thinking that history ends. Like a book, like a movie, like a story where one arc is wrapped up and a new one begins. It’s a mistake easily made by those who have enough personal distance from an event to know it only through a page, rather than through a face, a memory, a kinship or a name.

So if it is not your relative whose tiny body might lie in an unmarked grave, far from home, then it’s easy to think that what happened is over. It’s easy to say, as one commentator did earlier this week, that it’s “time to move on.” But you’d be wrong, because history doesn’t end, and those most directly affected by it do not forget.

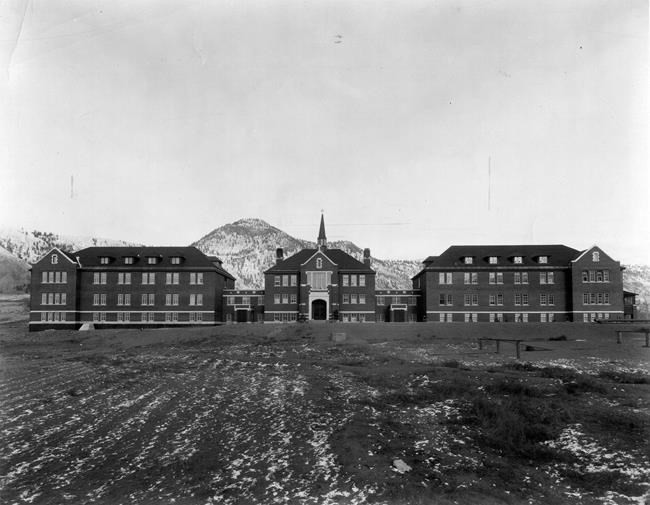

And when news broke last month that 215 unmarked graves had been found near the former Kamloops Indian Residential School on the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc First Nation, the grief that flowed from the discovery was a sorrow not just for a new revelation about history, but for a pain some have always known.

All between the coasts, survivors and their allies planted gardens of empty shoes, arranged in rows.

Survivors told us about the dead. They told anyone who would listen. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s work has documented at least 4,100 children who never came home. Many of their bodies were never returned to their families: too costly. Indigenous dignity is never an expense a colonial state is willing to bear.

Residential schools eventually ended; the way Canada acts on Indigenous lives never did.

And it’s true that the late 19th and early 20th centuries were a more dangerous time to be a child in Canada. Kids died at far higher rates than they do now, usually from disease, or infection. But Indigenous children in residential schools perished more than others, their bodies weakened by abuse, malnutrition and poor living conditions.

There were also the accidents, and the deaths born of trauma. Fires. Suicides. Children who froze or drowned while trying to escape, to get home, to get somewhere safe; by the TRC’s findings, as many as one in 25 children taken to the schools died. In the system’s earliest years, as many as half did not survive.

In half of cases, their cause of death wasn’t recorded. In a third of cases, even their names weren’t recorded. But each of them had someone who knew them, who loved them, and who remembered, and the fact of the graves was never really a secret.

So survivors and their communities always knew the graves were there, if not always precisely where. One has now been found. To locate others will require commitment from the governments and institutions responsible for them, but it’s a necessary step to know our own history.

The next step is to accept that this history never ended. It has carried on as an unbroken line, linking a system in which the bodies of Indigenous children were left to languish in unmarked graves, and a world today in which the bodies of Indigenous women are found with grim regularity stashed in ditches and dumpsters and rivers.

A world in which Indigenous children are still taken from their families at vastly disproportionate rates, only now through the child welfare system. A world in which Indigenous people are still more impacted by communicable disease than white Canadians, as shown through the disparate case and hospitalization rates for COVID-19.

All this is to say: residential schools eventually ended; the way Canada acts on Indigenous lives never did.

So if believing that history ends is the first mistake, then the second is to think that it’s preserved best in who we remember, rather than how. Because whenever advocates raise a call to rename places that bear the monikers of those responsible for some historical evil, critics often charge that they are seeking to “erase history.”

Those critics have it the wrong way around. Changing a name doesn’t erase history: Constantinople, for instance, became Istanbul without posing any threat to documenting the city’s time under the Roman emperor Constantine. What does erase history is letting it go untaught and unchallenged in the light of what we know.

So when you ask most Canadians what they learned about residential schools over the course of their own school education, and they reply “nothing,” that is history, erased. When we every day use roads or go to places that bear the names of the schools’ architects, and yet do not know the story behind the name, that is history, erased.

When we every day use roads or go to places that bear the names of the schools’ architects, and yet do not know the story behind the name, that is history, erased.

As a teen growing up in south Winnipeg, I drove to work most days down Bishop Grandin Boulevard, named for the Roman Catholic priest Vital-Justin Grandin. I used his name daily for years and yet, when it came to his key role in building the residential school system, I didn’t know, I didn’t know, I didn’t know.

This erasure might have been complete, were it not for the tenacity of survivors and their communities, for whom this was never a closed historical chapter. The architects of residential schools set a mission to wipe out cultures, languages and Indigenous peoples’ identities; they failed, though they did incalculable damage in the attempt.

A moment of gratitude, then, that survivors held the truth of this history safe, until more were willing to listen.

History, they say, is written by the victors, but what happened on these lands was not a war, and the children in those graves were not combatants. In the end, one system came away with all the power, and yet there are no winners, only heirs to a painful, often shameful past with which we are still learning to reckon.

So when movements gather steam to strip the names of people such as Grandin or Egerton Ryerson from streets and public buildings, it is not a proposal to erase history. In fact, it is doing the opposite: through these discussions, we are at last actually coming to know our history, to describe its effects and share its facts.

In other words: if you want to celebrate someone, then put their name on a road. Slap it on a structure of brick or asphalt or stone. But if you want to preserve history, well, then you have to teach it, and that begins with knowing the truth that, for too long, was allowed to stay hidden.

melissa.martin@freepress.mb.ca

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.