Genocide on the Prairies Hundreds of Indigenous children who simply vanished during Canada's brutal residential school 'final solution' are buried in unmarked, long-forgotten graves in Manitoba, researchers say

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 04/06/2021 (1648 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

It often started with a knock at the door.

Children were snatched from their parents’ arms and forcibly transferred by trucks, trains, planes and boats, with trails of tears left in their wake.

They were taken to strange, isolated institutions scattered across the country where they knew no one, had no connection to the land and were forbidden from acknowledging their heritage.

This, their captors called, “uplifting their character and broadening their aims.”

The schools were run like prisons: the children were stripped naked and dressed in uniforms, their heads were sheared, they were given identification numbers and new names, and they were beaten if they dared speak their native tongue.

This, their captors called, “elevating the Indian race.”

Indigenous political and social institutions were targeted for destruction. Land was seized and movement tightly restricted. Most importantly, families were separated to stop the transmission of cultural values from one generation to the next.

This, their captors called, the “inevitable march of civilization.”

Spiritual practices were punished and banned, objects of worship were confiscated and destroyed, knowledge-keepers and elders were persecuted and jailed and religious indoctrination was strictly enforced at the barrel-end of a rifle.

This, their captors called, “inculcating truths.”

The stated aim was to kill the Indian in the child.

Often, they just killed the Indian.

Children disappeared from the schools and no one searched for them. Some froze to death in harsh Canadian winters as they fled for home on foot. Physical and sexual violence was rampant. Emotional and spiritual abuse was institutionalized as formal policy.

The little ones who died — sometimes as young as three years old — were not afforded decent burials. In most cases, the Department of Indian Affairs refused to ship their bodies home to their parents, coldly asserting it would be too expensive to do so.

Far too often, parents weren’t even told their children had died, and the only death notification made was to the Indian Affairs civil servant responsible for the file. Meanwhile, political leaders and broader society agreed it was all for their own good.

Justice demands that people accused of crimes be prosecuted, defended and judged. But in this particular Canadian horror story, the majority of the perpetrators are dead, and many of the victims are, too.

What, then, is to be done? What does justice demand of us now?

“It is readily acknowledged that Indian children lose their natural resistance to illness by habituating so closely in the residential schools and that they die at a much higher rate than in their villages,” wrote Duncan Campbell Scott, the head of Indian Affairs, in 1910.

“But this does not justify a change in policy of this department, which is geared towards a Final Solution of our Indian Problem.”

In 1914, Scott wrote that “fifty per cent of the children who passed through these schools did not live to benefit from the education which they received therein.” Six years later, at his behest, the federal government made attendance at residential schools compulsory.

“When the school is on the reserve, the child lives with its parents, who are savages and though he may learn to read and write, his habits and training mode of thought are Indian,” said Sir John A. Macdonald, Canada’s first prime minister, in 1883.

“He is simply a savage who can read and write.”

Vital-Justin Grandin, the Catholic priest and bishop who was honoured by the City of Winnipeg by putting his name on a major thoroughfare, “led the campaign” for the creation of the Indian Residential School System.

“We instill in them a pronounced distaste for Native life so that they will be humiliated when reminded of their origin. When they graduate from our institutions, the children have lost everything Native except for their blood,” Grandin wrote in 1875.

There were other, more practical benefits, too — namely, the state’s possession of Indigenous children would pacify potential revolutionary impulses.

In 1886 — one year after the North-West Resistance led by Louis Riel — Indian Affairs school inspector J.A. Macrae noted it was “unlikely” any “tribe or tribes” would give “trouble of a serious nature” when their children were “under government control.”

For their efforts, men such as Macdonald, Scott and Grandin were praised and celebrated. They remain praised and celebrated to this day. There are roadways and neighbourhoods and municipalities named in their honour.

Their words and deeds — and the words and deeds of many others like them — bring to mind the famous phrase from the German-Jewish philosopher Hannah Arendt: “the banality of evil.”

Evil need not be perpetrated by monstrous men, according to Arendt, who argued it is often the work of mediocre, mundane individuals more motivated by professional promotion and personal interest than fanaticism or sadism.

This is particularly true when individuals are backed by religious authorities. Such men are neither “perverted nor sadistic,” but “terribly and terrifyingly normal,” and this normality is “much more terrifying than all the atrocities put together.”

“We instill in them a pronounced distaste for Native life so that they will be humiliated when reminded of their origin. When they graduate from our institutions, the children have lost everything Native except for their blood.”– Bishop Vital-Justin Grandin, in 1875

Macdonald was a witty man with many female admirers who had a public reputation for enjoying a drink. When his first child died at 13 months old in 1848, he kept a small box of the boy’s toys for the remainder of his life, struggling to recover from the loss.

Scott was a successful writer and dramatist, in addition to being an accountant and civil servant, who published a dozen volumes of poetry in his life and helped found the Ottawa Little Theatre and the Dominion Drama Festival.

Grandin was a pious man beloved by parishioners, an early defender of French-language rights in Western Canada and an advocate for the Métis people.

These men were not cartoon villains. Nevertheless, their actions were evil.

They are responsible for a systematic, state-sponsored campaign aimed at the destruction of Indigenous peoples as distinct “legal, social, cultural, religious and racial entities in Canada,” which continues to echo through history and reverberate to this day.

It was more than a “dark chapter” in Canadian history, or a “stain” on the legacy of our country’s forefathers.

It was cultural genocide.

A national crime.

● ● ●

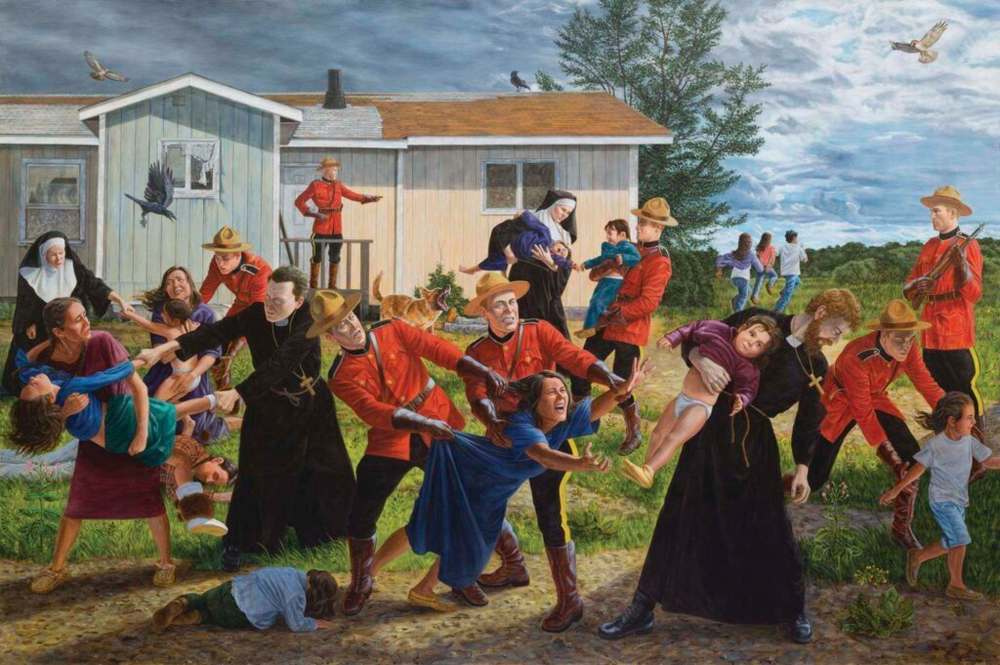

There is a painting that used to hang in the Winnipeg Art Gallery.

In it stands a small wooden house: a simple bungalow with multicoloured tiles fashioned to the roof. Dense bush and open fields flank the home to the east, and to the west, dark and foreboding clouds form in the sky.

Three children run from the home at full sprint. Their backs are turned to the viewer as they race for the bush in the distance. The scene they are fleeing — the one transpiring in front of the house — is pure chaos.

Seven Mounties are dressed in traditional red uniforms, with tan, wide-brimmed hats and long leather gloves. One of them stands on the house’s front porch with his arm extended to the side, pointing at the children trying to escape.

The rest of the officers are scattered in front of the home; one stands to the side holding a rifle. The others are snatching Indigenous children away from their wailing mothers. Two priests and two nuns help carry out the kidnappings.

In the centre of the frame is a mother wearing a long blue dress. She lunges forward, reaching out for her child, who is being carried off by a bearded priest with a wooden crucifix dangling from his neck.

The mother’s fingers grasp helplessly in the air. Two Mounties restrain her, grabbing her dress, grabbing her arm, grabbing her hair, taking hold of anything they can to separate her from her child.

Her mouth is open, transfixed in horror, frozen in a scream.

There are other mothers too, battling to save their children. Perhaps they will succeed. Perhaps the children fleeing to the bush will escape their would-be captors. But the mother in the blue dress appears to have lost the struggle.

Her child will be taken.

Late last week, Canada learned the fate that befell 215 such children at a residential school in Kamloops, B.C. — one of the more than 130 institutions that operated in this country with the help of various Christian churches, from the early 1880s until 1996.

Or white Canada learned of their fates, that is. For Indigenous people, the discovery of the unmarked burial site on the grounds of a former residential school could not have been less shocking.

Sickening and traumatizing, yes.

Surprising, no.

There have been stories of dead Indigenous babies buried below our feet for decades. These stories have long been shared in Indigenous communities. The rest of us just haven’t been listening.

In 2015, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission published a 266-page report entitled Missing Children and Unmarked Burials.

“Many, if not most, of the several thousand children who died in residential schools are likely to be buried in unmarked and untended graves. Subjected to institutionalized child neglect in life, they have been dishonoured in death,” the report said.

The official death toll of children in Canadian residential schools is roughly 4,100, but it’s believed there could be as many as 15,000 victims. In 2009, the TRC asked the federal government for $1.5 million to locate and preserve unmarked burial sites.

The request was denied.

We can’t pretend we didn’t know. We can’t pretend they didn’t tell us. And as Senator Murray Sinclair, chairman of the TRC, said this week in a video statement, there will be many more grim discoveries to come. On Thursday, Sinclair called for an independent investigation to examine all burial sites near former residential schools.

This is not a Kamloops story.

This is a story that can be told from countless communities across Canada.

The painting in question — the one that used to hang in the Winnipeg Art Gallery — is called The Scream. It is a part of Cree artist Kent Monkman’s exhibit Shame and Prejudice: A Story of Resilience, which opened in Winnipeg in the fall of 2019.

The exhibit — which serves as a gut-wrenching, chilling indictment of a whitewashed chapter in the history of Canadian colonialism — continues to tour art galleries across the country.

Reflecting on the painting, Monkman has said it is the one piece in the series that he can’t bring himself to talk about.

“The pain is too deep,” he said.

“We were never the same.”

● ● ●

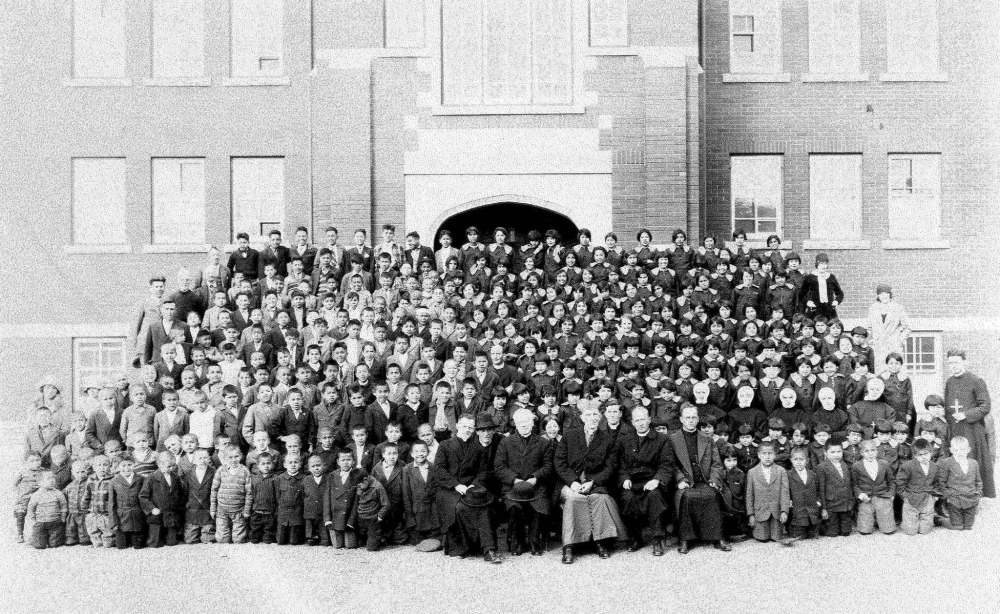

The Brandon Indian Residential School — the old red-brick building from the faded and grainy photographs, or the ruins where local teenagers escaped for years to drink beer — is gone.

Today, not even the rubble remains at the site north of the city, high upon a bluff overlooking the valley below. The tops of a few of Brandon’s taller buildings are visible from the vantage point, jutting out above the trees in the distance.

On a recent morning, there were sounds of grasshoppers hidden in the tall prairie grass and birds chirping from the trees. A winding dirt road leads up to the spot where the school once stood.

In recent days — mostly since the discovery of the mass burial site at Kamloops — people have left items in honour of the children who died while attending the Brandon Indian Residential School.

There are shoes left behind in the dirt. Stuffed animals and children’s toys. A bouquet of fresh flowers — pink and purple, yellow and white — resting in a glass jar. There is a children’s book that tells the story of a father who plants a tree when his son is born.

As the child grows, the tree grows with it.

An orange shirt — emblazoned with the phrase Every Child Matters — is hanging from the branches of a tree in the bush. Nearby, someone has left five cigarettes on a rock as an offering to those who have been lost.

There is no sign left of what once stood here; no sign left of what was done in this spot.

This was a crime scene; in some ways, it still is.

Deeper into the bush, about a kilometre-and-a-half north of the old school site, down through a water-soaked slough and over a barbed-wire fence, there is a small cemetery. It would be difficult to know it was a burial site at all, if not for the cairn in the centre of the plot.

The stone monument stands about a metre-and-a-half tall. On the front is a plaque with the names of 11 children who died while attending the school inscribed into the metal.

Lydia Wesley. Rebecca Spence. Cornelius Linklater. George Byrd. Angus Sunkawasky. Sam Youngskunk. Mary Sutherland. Henry Swanson. Ewart Monias. Roderic Beardy. John Kirkness.

Four stuffed animals sit at the foot of the cairn, and resting on the edge of the plaque are 11 small pebbles — one for each name. The land is flat and trees line half of the cemetery, which backs onto farmland.

In the past, small white crosses stood to mark the 11 children known to be buried here. Today, the crosses have broken down and fallen over, hidden in the long, overgrown grass within the fenced-in grounds.

According to researcher Katherine Nichols, a forensic anthropologist who has extensively studied the history of the Brandon residential school, there are likely far more children buried here.

Sioux Valley Dakota Nation believes there could be 104 Indigenous children buried at three sites near the former school. In the first 16 years of the school’s history alone, at least 51 students died.

There is an obvious question to be asked: how many schools for white children in Canada had cemeteries? Because most — if not all — residential schools for Indigenous children did.

● ● ●

It was the summer of 2018 and Lorena Fontaine, an associate professor at the University of Winnipeg and a member of Sagkeeng First Nation, was visiting the site of the former Brandon residential school.

The daughter of residential school survivors, Fontaine had been invited to the location by members of Sioux Valley Dakota Nation, a community that had many children taken to the school during its years of operation.

After walking into the bush to look at the “poorly-maintained cemetery” to the north, Fontaine and the others returned to the spot where the school once stood. The school operated from 1895 to 1972, before being demolished in 2000.

“We were talking and they mentioned there was a second burial ground. I asked them where it was and they said, ‘Oh, it’s over there where the trailer park is.’ I asked, ‘Oh, like beside it?’ And they said, ‘No, it’s underneath the trailer park,” Fontaine recalled.

“I just felt sick to my stomach. I felt ill…. And then I became very angry when I found out about the history of that burial ground.”

The fact there is a memorial — as insufficient and neglected as it may be — for victims of the Brandon residential school is largely due to the work of one man: Alfred Kirkness, who attended the institution as a child.

In the early years of the school, children who died were buried at a site about a kilometre-and-a-half to the south, near the Assiniboine River. Later on, students who died were buried north of the school, in the area where there now stands a small cairn in their honour.

In 1921, the City of Brandon took over the land on which the first burial ground was located. The land was cleared sometime during the Great Depression and municipal workers removed the gravestone markers.

Slowly, year after year, Kirkness watched as the resting place of the victims of the Brandon residential school was turned into a city park.

Beginning in the early 1960s and lasting until at least 1971, Kirkness mounted a campaign to fight back against the amnesia that had swept across the city. He wrote to the media, to the mayor and to various government officials demanding something be done.

In 1963, Kirkness, alongside a few others, took matters into his own hands, placing modest white markers on the burial site near the river, which — by that time — was a popular park where children would play and swim in the summer.

In 1972, the Brandon Girl Guides placed a commemorative monument at the site — a plaque reading “Indian Children Burial Ground” bolted into the front of a large boulder — and built a fence around the area.

Due to Kirkness’s tireless efforts, government officials eventually constructed the cairn at the cemetery north of the former school and agreed to fence in the area so it wouldn’t be littered with cow dung.

By the time Kirkness died in 1980, both burial grounds were formally recognized, with modest monuments erected in honour of the dead.

Kirkness’s final resting place, alongside his wife Lily, is plot 45 B 15 at the Brandon Municipal Cemetery. It is a peaceful spot with a small headstone in the neatly manicured grass.

It is similar to what he wanted for the victims of the Brandon residential school.

It is what he spent years fighting for.

And while Kirkness’s fight on behalf of those victims was not in vain, the results he saw during his lifetime were short-lived.

Today, the cemetery north of the school has fallen into disrepair. And in 2001, the City of Brandon sold Curran Park — the site of the earlier burial ground — to a private buyer for $130,000. The small memorial that once stood on that land is now gone.

The fenced-in area has disappeared. The large boulder sits near the entrance to the site, which is now called Turtle Crossing Campground, in the ditch along a gravel road. And the plaque is missing, its absence clearly visible on the stone.

On the ground in front of the boulder, next to three dandelions sprouting from the earth, is a small bouquet of wildflowers wrapped in pink ribbon.

The flowers are wilted.

● ● ●

For roughly a year, from late 2013 to late 2014, Scott Hamilton spent evenings and weekends hunched over his desk at home, his face aglow with the light from his computer monitor, as he searched for unmarked gravesites.

The anthropologist and professor at Lakehead University in Thunder Bay had been hired by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission to see if he could help identify suspected sites where victims of residential schools had been buried and forgotten.

For Hamilton, it was as if he was on a grisly cold case, and he spent countless hours using satellite imagery to locate and identify the sites of residential schools and then search out markers that could indicate former cemeteries and burial spots.

“My life stopped for about a year. This was an evenings and weekends job after my day job was done. Quite frankly, I don’t even know how many hours I spent doing this work. I got lost in it,” he said.

“We don’t know, at any of these places, what the real number of deaths are. And that kind of haunts one, thinking about all of these families, who for decades and decades and decades, had to wonder, ‘What happened to my child?’”

In a report he wrote for the TRC, Hamilton said he believed that most, if not all, residential schools would have had a cemetery, given the suspected death patterns at the institutions throughout the years.

“People of goodwill can make a huge difference. At the Elkhorn cemetery, there is a fence around it. The grass is cut. The crosses are maintained. It’s a quiet place of veneration and respect.”– Scott Hamilton

“While comparatively few (residential school) cemeteries are explicitly referred to within the surviving literature, the age and duration of most schools suggests that cemeteries were likely associated with most of them,” he wrote.

“In search of those cemeteries, the area surrounding each school was systematically examined using the available maps and satellite imagery. In some cases, they were not evident, but possible cemeteries were detected in a surprisingly large number of others.”

As a result of this work, Hamilton said he “wasn’t remotely surprised” when news broke about the discovery at the former Kamloops residential school. He also wasn’t surprised that after the TRC reports were published in 2015, not much happened.

Since the TRC calls to action were issued, only 10 of 94 recommendations have been fully implemented.

“In Canada, we have this long tradition of calling a royal commission and then filing it away and forgetting about the findings of the royal commission,” Hamilton said.

When asked about Manitoba residential schools — there were 14 institutions officially recognized by the TRC — Hamilton said what struck him most was the cemetery near the former school in Elkhorn, a small, rural community in western Manitoba, located just off the Trans-Canada Highway.

“People of goodwill can make a huge difference. At the Elkhorn cemetery, there is a fence around it. The grass is cut. The crosses are maintained. It’s a quiet place of veneration and respect,” Hamilton said.

“And then in other places, they’re forgotten, abandoned and overgrown, or disrespected entirely. In those latter places, we need to catch up and do the right thing, as has been done in Elkhorn.”

The Elkhorn cemetery sits off a gravel road on the outskirts of the town, inside a barbed-wire fence with a No Trespassing sign. It is surrounded by trees and lush bushes, which blow in the breeze on windy days.

A large white cross stands at the front of the cemetery, with 24 smaller white crosses spread across the grounds.

The American poet and undertaker Thomas Lynch once remarked that the “meaning of life is connected, inextricably, to the meaning of death.”

“Mourning is a romance in reverse, and if you love, you grieve and there are no exceptions — only those who do it well and those who don’t,” Lynch wrote.

“And if death is regarded as an embarrassment or an inconvenience, if the dead are regarded as a nuisance from whom we seek a hurried riddance, then life and the living are in for like treatment.”

● ● ●

In the aftermath of the Kamloops discovery, Winnipeggers — like people in cities across Canada — engaged in acts of public, collective mourning.

Shoes lined the steps of the Manitoba Legislative Building, and the pathway leading to St. Boniface Cathedral was flanked on both sides by sticks with orange ribbons. There were sacred fires lit, ceremonies held and graffiti scrawled across the city.

Winnipeg Mayor Brian Bowman publicly said it was time to consider changing the name of Bishop Grandin Boulevard, and flags at government buildings fluttered at half-mast.

But the fact remains the situation in Kamloops is little different than the situation in Brandon, and there were no similar mass outpourings of grief when news of dead children buried near Manitoba’s second-largest city began making headlines in 2015.

Tom McMahon, who served as general legal counsel for the TRC and was executive secretary of the Aboriginal Justice Inquiry, said he believes the reaction this time around is due to a “gradual increase in our empathy” as a society.

The AJI — which, like the TRC, was chaired by Murray Sinclair — was held in the aftermath of the killing of J.J. Harper in 1988, an unarmed Indigenous man shot to death in the North End of Winnipeg by police officer Const. Robert Cross.

“This is the reaction that should have been there all along,” McMahon said.

“I believe that former president (Barack) Obama was right when he said (quoting Martin Luther King Jr.), ‘The moral arc of the universe is long, but it bends toward justice.’”

There are more unmarked graves to be uncovered across the country — likely hundreds — including here in Manitoba. At least 30 children died at the Cross Lake residential school, which burned down not once, but twice.

The Birtle Indian Residential School was a large farming operation, and although there is no record of a cemetery, researchers have placed it into the “high risk” category for possible deaths. It is also believed there are unmarked graves in Sagkeeng First Nation.

The reality is there could be unmarked burial grounds at nearly every residential school that operated in Manitoba. There were 18 institutions in the province, although only 14 made the official TRC designation of residential schools.

Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs Grand Chief Arlen Dumas has called for funding to conduct forensic investigations across the province, while Perry Bellgarde of the Assembly of First Nations said such searches would turn up further evidence of the “genocide of our people.”

Lorena Fontaine said that as an immediate first step, the cemeteries near the Brandon school need to be properly protected and memorialized. There have already been calls for the city to buy back the land where a campground currently stands atop the place where Indigenous children rest.

“I think a lot of non-Indigenous people still see this as historic. They treat it that way and they don’t consider the fact that we’re still living the legacy of this. We’re still living with the repercussions.… This still affects people walking around today,” Fontaine said.

“The communities need to know they have relatives in those burial grounds. We need to have those sites protected. It needs to be respected as a burial ground. And we need to do ceremonies for those children who likely didn’t have proper burials.”

The legacy of residential schools is still with us today.

In Manitoba, 90 per cent of the kids in the child-welfare system, 75 per cent of the men locked up at Stony Mountain Institution and more than two-thirds of the homeless population are Indigenous.

One in three Indigenous children in Winnipeg live in poverty.

As Dumas said in the aftermath of the Kamloops discovery, “It is not ancient history when we are still uncovering graves.”

In 1920, while speaking in favour of the bill that would mandate the attendance of all Indigenous children between the ages of seven and 15 at residential schools, Duncan Campbell Scott said his goal was to “get rid of the Indian problem.”

“Our object is to continue until there is not a single Indian in Canada that has not been absorbed into the body politic and there is no Indian question,” Scott said.

By Scott’s own criteria, he failed.

Canada failed.

Indigenous people are still here, they are still with us, their cultures are still alive and despite their continued oppression, they thrive in myriad ways.

We have ignored their plight and collective trauma for far too long, while whitewashing our history and excusing the sins of our forefathers.

No longer shall we turn a blind eye to what has happened here.

That ends with the bodies of 215 children found buried in unmarked graves in Kamloops.

ryan.thorpe@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @rk_thorpe

Ryan Thorpe likes the pace of daily news, the feeling of a broadsheet in his hands and the stress of never-ending deadlines hanging over his head.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Friday, June 4, 2021 10:24 PM CDT: Fixes typo.