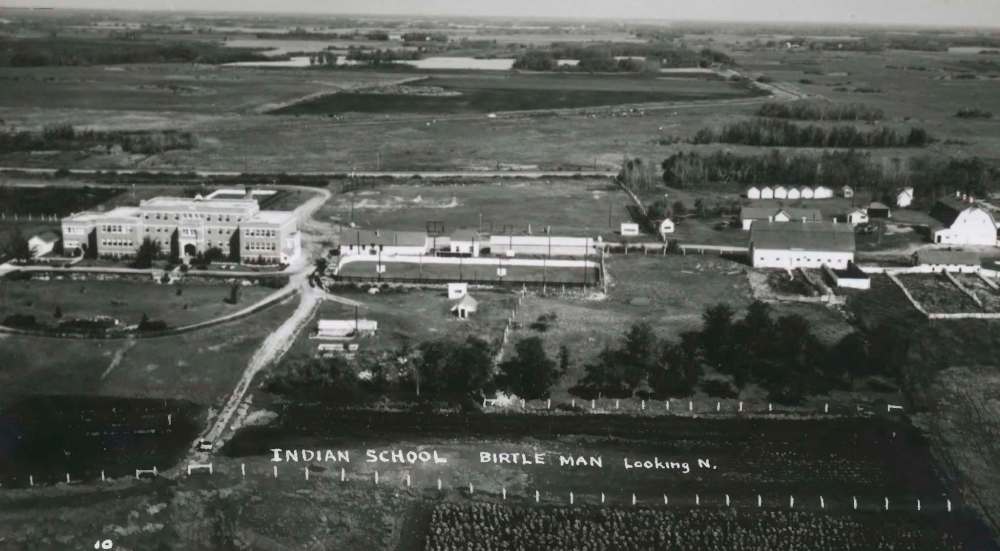

Burial site likely at Birtle school

Birdtail Sioux First Nation seeks proper examination of former residential school lands

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 04/06/2021 (1741 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Heath Bunn has survivor’s guilt.

The Dakota band councillor’s parents met at Birtle residential school, one of a dozen in Manitoba suspected of having unmarked graves on-site.

“Each young girl and boy could’ve had families,” Bunn said from Birdtail Sioux First Nation, 285 kilometres west of Winnipeg. “That kind of loss is unfathomable.

“Just thinking about that, you’re so happy your parents survived — but you feel that.”

Last week, a band in Kamloops, B.C., announced a geographic survey had revealed unmarked burial grounds, containing the remains of 215 children.

The news caused international outcry, and prompted Ottawa to put up funding for similar ground searches. But it’s also ripped open unhealed wounds in Indigenous families across Canada.

“Everyone’s going through a grieving process,” said Bunn. “We have anger. We need to get to the bargaining stage, and finally acceptance.”

The Birtle school housed Indigenous children from 1888 to 1970, and had documented deaths from pneumonia and tuberculosis. Like many Prairie schools, students often were farming more than learning, while records show it often lacked potable water and at times was only heated to 10 C in the winter.

In Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada testimony, Birtle survivors recalled the principal watching them while they showered, and never having a nurse check on students who were sick.

Bunn still doesn’t know what exactly his parents lived through.

“It needs to be brought to light, but in some cases, it’s so tragic to bring up their personal experiences.”

The school generally housed older pupils, many who already attended the one in Brandon, and both housed students from across Manitoba.

Bunn said other First Nations might want to bring bodies home.

He thought of the last time he walked through the building.

“It’s a very eerie feeling when you go and see the tiny beds,” said Bunn. “A lot of the survivors block it out, and don’t want to speak to it.”

He wanted Canadians to understand residential school survivors had ghastly role models for parenting, and in turn didn’t know how to raise their own children.

“A lot of people have a resentment toward their parents, but it’s not their fault,” said Bunn, who said the fallout from Birtle can be seen in drug addiction, and limited economic opportunities.

“It’s a never-ending cycle.”

An academic report last month said it’s likely a burial site is next to the school, and Bunn’s community is trying to find out how to get it properly examined.

“I believe every one of them need to be looked at,” he said.

On Thursday, bureaucrats told MPs federal funding had never been designed to allow Indigenous communities to do burial ground searches, despite First Nations asking for it for years.

Officials confirmed a Free Press report the band in Kamloops did its search using a $40,000 grant from the Canadian Heritage department, generally intended for research and commemoration.

On Wednesday, the Trudeau government pledged to fast-track $27 million, originally meant to commemorate sites, to instead be used to conduct such ground searches.

Stephanie Scott, head of the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation in Winnipeg, told MPs survivors are aware of bodies buried within the walls of schools, and also in hills and riversides, as children tried running away.

“These sites are in fact crime scenes, and the discovery at Kamloops has triggered a new urgency in survivors and their families to share their truths, while they still can,” Scott testified.

She added the Winnipeg centre has no long-term funding, despite its efforts to document testimonies.

“We are racing against time. We often hear from survivors that they have fewer tomorrows than they have yesterdays,” she said.

Long Plain First Nation has felt that urgency, spending tens of thousands of dollars searching the grounds of its reserve near Portage la Prairie, at a cost of roughly $8,150 per acre.

The band opted to search all areas undergoing construction a year ago, because elders said their former classmates are probably buried in unmarked graves.

A ground-radar search revealed four sites that required further analysis, including one near a hotel that opened in 2019. Ultimately, the differing soil conditions and wet pockets turned out to be anomalies.

Long Plain Chief Dennis Meeches said his First Nation wants to search other areas to bring some closure and healing to families.

dylan.robertson@freepress.mb.ca

History

Updated on Friday, June 4, 2021 6:27 AM CDT: Adds photo