Giving colonialism a shake Artist Kent Monkman intends to unsettle viewers as exhibition stops at the WAG

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 26/09/2019 (2359 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

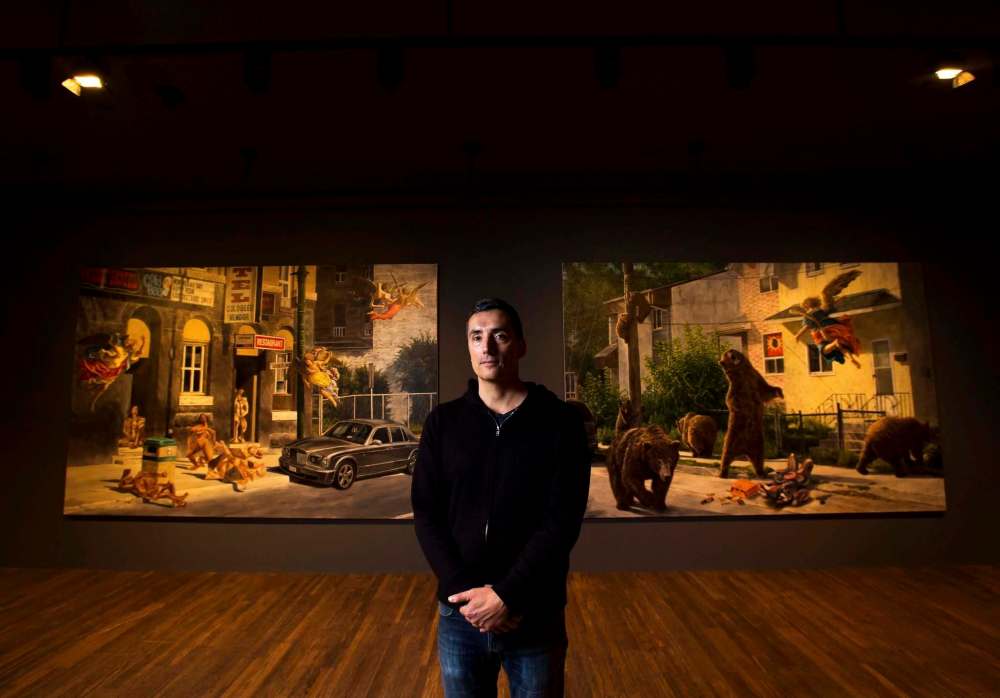

Two years after its debut, Kent Monkman’s Shame and Prejudice: A Story of Resilience is finally coming to Winnipeg.

Event preview

Shame and Prejudice: A Story of Resilience

● By Kent Monkman

● Winnipeg Art Gallery

● Opens Sept. 27, to February 2020

Commissioned in 2014 by Barbara Fischer, curator of the University of Toronto art museum, the show premièred with a bang in 2017 as a part of the celebration for Canada 150. It has been touring across the country ever since.

The exhibition opens Friday at the Winnipeg Art Gallery and, in a sense, its journey to Winnipeg is a journey home — at least for Monkman.

“I grew up going to the Winnipeg Art Gallery,” Monkman says. “I did Saturday morning art classes there. I was lucky to do that as a kid. That shaped my artistic identity.

“I was in to drawing and making up plays, stories, and puppet shows.”

A young Monkman liked to visit the Manitoba Museum and went to Kelvin High School before moving east to study commercial art at Sheridan College in Brampton, Ont.

Monkman, a First Nations artist of Cree and Irish ancestry, is primarily based in Toronto these days, but he also spends part of his time on a farm in Ontario’s Prince Edward County. “I have a studio out there,” he says. “But I don’t run the farm. I’m too busy!”

Shame and Prejudice will stop in Winnipeg for six months before it wraps up its tour at the Museum of Anthropology at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver in May 2020.

“The exhibit is situationally and contextually relevant to Winnipeg in its subject matter,” says Jaimie Isaac, curator of Indigenous and contemporary art at the Winnipeg Art Gallery and the exhibit’s project manager.

“In a city with more than 80,000 Indigenous people living in the urban centre, it is important to tell the story of colonialism in Canada and its ongoing impact on Indigenous peoples and Canadians alike.”

Monkman does this through the creation of representational paintings inspired by 19th-century landscapes… but with a contemporary twist that disrupts the narratives viewers have come to expect. Miss Chief Eagle Testickle, Monkman’s gender fluid two-spirit alter-ego, is just one of the devices used to challenge these expectations.

“I had the idea 20 years ago,” says Monkman. “I wanted to challenge the objectivity of the artist. I was thinking a lot about the ego of the artist, the subjectivity of the artist. I wanted to reserve the gaze and turn the gaze back on the European settlers.”

Two-spirit is a concept present in some Indigenous communities. It refers to someone who identifies with both the masculine and feminine. The gender binary of masculine or feminine was introduced to these communities during colonization.

“I was thinking a lot about colonized sexuality,” Monkman says. “I wanted to create a character very powered in her sexuality and gender.”

In Shame and Prejudice, Miss Chief Eagle Testickle guides visitors through Canada’s often untold history — a history of immense loss and powerful resilience.

“It’s organized by chapters in time and history, using Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice book of manners as the framework,” Isaac says. “Through Monkman’s complex compositions, he merges myth, spirituality and art history to intelligently convey difficult narratives and disrupt memories that complicate and unpack what Canadians know about the formation of their country and the devastations Indigenous people continue to face.”

“In adopting historical iconography, the usage of modernist and old masters’ styles and methods present a canny familiarity as a way for the audiences to see the role of art history in framing colonialist narratives. Subsequently, Monkman’s artwork subverts and informs.”

This quality of disruption and subversion isn’t unexpected. In fact, it’s completely intentional.

“It’s always a deliberate choice,” Monkman says. “I used to work in abstraction but I realized that language was too limited, the vocabulary too personal. I wanted to talk about colonization in my work.

“I set out on a journey to investigate the art, the land and the First Peoples. I decided to return to my roots as a representational artist because I could draw and I could paint. I decided that I was going to forget about having that personal vocabulary and emulate the historical painters that were making images of First Nations people in the 19th century.”

Monkman’s decision has led him to becoming one of Canada’s most prolific and prominent artists, Isaac says.

“His work challenges Canadian dominant narratives with the re-telling of histories/herstories that demonstrate comparative knowledge,” she says.

Monkman admits the process of creating representational art can be challenging, but he has a dedicated process to guide him through.

“When I started to look at all the old masters I began to realize how difficult it actually is to make representational work,” says Monkman. “It starts with the concept, whatever that might be. I think a lot about what exactly I want to convey thematically. It starts with a pencil sketch and from there it goes to a colour study where I work out compositional ideas.”

And Monkman’s not working alone: he has many assistants in the style of the atelier system.

“I have a team of painters, fabricators and administrative people that work with me in my studio,” he says. “We’ve developed a very unique methodology.”

As an Indigenous artist, Monkman has faced his fair share of criticism, but has also developed a unique method for working within a field built upon colonial structures.

“I think that colonial structure is embedded in the institution,” he says. “There has definitely been a very colonial way of representing First Nations people that is slowly changing. I’ve seen change over the last 25 years. It is slow… but there is movement.

“You can never really decolonize institutions because they are colonial in their roots,” he adds, “but we can de-centre that point of view. We can reflect on our art history moving away from purely European settler perspectives and think about what the history of this country has been for the last 150 years from an Indigenous point of view.”

Are viewers ready for an Indigenous point of view? It’s hard to say, but Isaac is confident that audiences will find it a fulfilling experience.

“I think audiences will feel full,” she says. “Full and yet wanting of more.”

Frances.Koncan@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @franceskoncan