Life in solitary takes torturous toll Isolation practices in Canadian prisons regularly exceed limits set in international law

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 27/04/2021 (1691 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Devon Sampson, a 34-year-old man diagnosed with schizophrenia, hanged himself at Stony Mountain Institution in 2013. He spent 187 consecutive days in solitary confinement prior to his death; during a previous incarceration, he spent 294 consecutive days in solitary.

For decades, isolating inmates — often those with serious psychiatric conditions — in solitary confinement was a common practice in Canadian prisons. Officially, it was called “administrative segregation,” a sanitized, bureaucratic label for something far more troubling: state-endorsed torture.

CSC RESPONDS

SIUs are about helping inmates and providing them with the continued opportunity to engage in interventions and programs to support their safe return to a mainstream inmate population as soon as possible. SIUs are not about punishment or causing harm. They are meant as a temporary measure to help inmates adopt more positive behaviours that keep the institution as a whole, safe and secure.

SIUs are about helping inmates and providing them with the continued opportunity to engage in interventions and programs to support their safe return to a mainstream inmate population as soon as possible. SIUs are not about punishment or causing harm. They are meant as a temporary measure to help inmates adopt more positive behaviours that keep the institution as a whole, safe and secure.

The law is clear. While in an SIU, inmates have access to the same types of programs, services and activities as inmates in a mainstream inmate population. They are visited daily by staff, including their parole officer, health care professionals, correctional officers, primary workers, Elders and Chaplains as well as other inmates and visitors. Inmates must be provided with the opportunity to spend a minimum of four hours a day outside their cell, including two hours a day for meaningful human contact.

The legislation guiding SIUs recognizes that there are situations when an inmate may be held in their cell for longer, for example, if they refuse to leave. This is their right. We continue to make active offers for time out of cell, including access to programs and meaningful contact with others. We encourage inmates not only to take these opportunities but also to engage in them.

The prolonged use of solitary — defined as 15 days and up – was classified as torture under international law in 2015. Four years later, the federal government mandated Correctional Services Canada to put an end to the practice.

Instead, it continues to this day – including at Stony Mountain north of Winnipeg — but under a different name.

“This is a very serious issue. Our concern is that this is just the tip of the iceberg in terms of people being subjected to functional solitary confinement. It’s bad. It’s just really bad,” said Catherine Latimer, the national executive director of the John Howard Society.

“You’ve got to stop torturing them and subjecting them to these long solitary confinements.”

The psychological impact of solitary on inmates is well established, something Ryan Beardy, a former gang member and current freelance journalist, mentor and justice advocate, knows all too well.

Beginning as a youth and continuing into adulthood, he repeatedly spent time in solitary confinement during stints at various correctional facilities, including Stony Mountain. Now, he works with the John Howard Society to raise awareness about prison conditions in Canada, and organizes a weekly support group for men in Winnipeg.

“I don’t know how many times I was looking through a crack in the wall just wishing that a nurse would walk by, or a guard would walk by, just so that I could ask them the time. Human interaction is huge. When we don’t have human interaction, we actually forget how to interact,” Beardy said.

Beardy points to a growing body of research that suggests not only does solitary confinement have a psychological impact on inmates, but a physiological impact as well. Studies have shown that extreme isolation can inhibit the development of neurons in the brain.

“If in any country, someone was sent to prison and they chopped off their limb, that would be barbaric. It would be a huge violation of human rights. So why is it all right in Canada to send someone to solitary confinement where they’re losing neurons?” Beardy asks.

“We shouldn’t have it in Canada at all.”

Craig Haney, an American psychologist who has studied the impact of solitary confinement on prisoners, has said the endless monotony and lack of human contact can trigger a “descent into madness.” Symptoms can include suicidal ideation, depression, paranoia, panic attacks and hallucinations.

“You’ve got to stop torturing them and subjecting them to these long solitary confinements.” – National executive director of the John Howard Society Catherine Latimer

For years, the Office of the Correctional Investigator — the federal prison ombudsman — has sounded the alarm about the use of solitary, pointing to the high number of cases where inmates killed themselves during long periods of isolation.

In 2015, the United Nations adopted an amendment to the Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners, known as the “Nelson Mandela Rules,” which classified the prolonged use of solitary as torture, and cruel and unusual punishment.

Stony Mountain Institution is Canada's oldest federal penitentiary, but also the country's deadliest

Posted:

IT HAS BEEN 59 years since the Canadian state last slipped a noose around the neck of a prisoner, and more than four decades since the gallows were formally abolished in this country, yet death continues to lurk behind the bars of Stony Mountain Institution north of Winnipeg.

And yet, solitary confinement continued in Canadian prisons until 2019, when the federal government passed a law ostensibly banning it. Instead, the feds said, solitary would be replaced with new “structured intervention units.”

Solitary is the term used internationally to refer to the practice of confining a prisoner in a cell for more than 22 hours per day without meaningful human contact. With structured intervention units, inmates are supposed to have four hours outside of their cell each day, with two hours of meaningful human contact.

To implement the change, CSC was given $300 million. The agency’s annual budget is $2.6 billion.

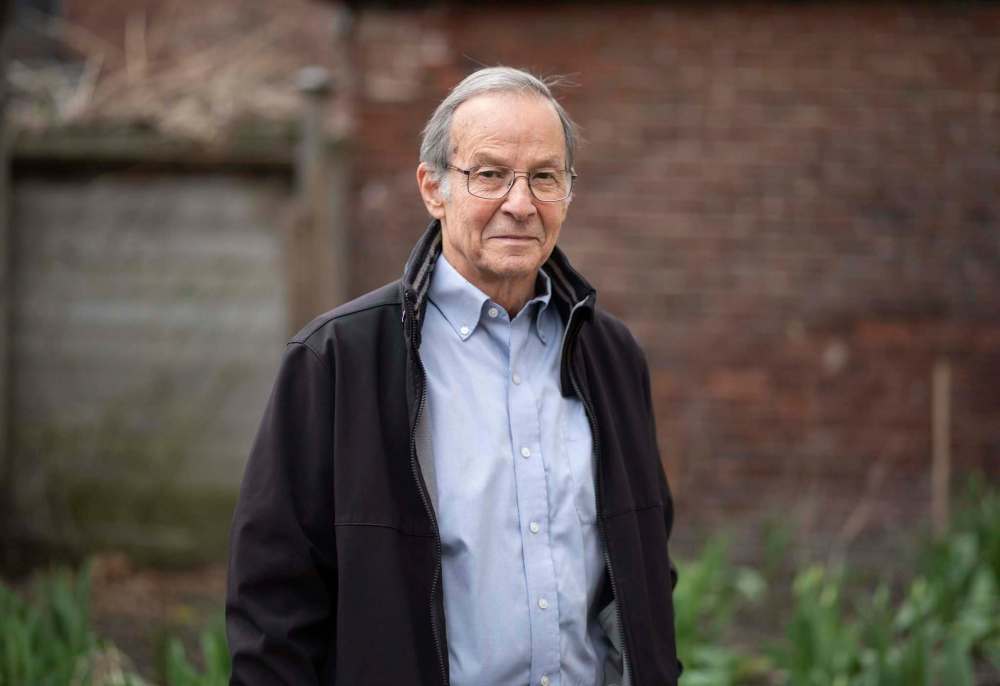

The federal government also set up a committee of independent experts tasked with reviewing progress in phasing out the use of solitary. One of the committee members was Anthony Doob, a criminologist and professor emeritus at the University of Toronto.

The only problem, according to Doob, was that CSC stonewalled the committee’s work.

The committee had accomplished “absolutely nothing” by the time its one-year term was up because CSC refused to turn over the requested data on the use of solitary and the implementation of structured invention units, Doob said.

“The people who were on (the task force) were people Correctional Services of Canada didn’t want on it. There were several people who they were not going to be able to push around… But they succeeded anyways by saying, ‘Well, we’re just going to close the door in your face,’” Doob said.

“In effect, they control things by having the key to the door.”

After Doob went public with the way CSC stifled their efforts, the federal government forced the agency to hand over the data.

Even though the committee had been dissolved, Doob was still interested in what the data had to say. He and Jane Sprott of Ryerson University have produced three reports showing the practice of solitary confinement continues in Canadian prisons — just as structured intervention units.

According to their research, an estimated 28 per cent of all stays in the new units amount to solitary confinement, with an additional 10 per cent constituting torture under the Nelson Mandela Rules.

“There is no question that there is oversight. But the question is: What does that oversight consist of?” – Anthony Doob, a criminologist and professor emeritus at the University of Toronto

In a written statement sent to the Free Press, CSC said that an external review kicks in if an inmate does not spend the required four hours per day outside of their cell, or receive the necessary two hours of meaningful human contact, for five consecutive days, or 15 out of 30 calendar days. The importance of this review process, CSC says, “cannot be understated.”

But according to Doob, like with many other facets of CSC operations, there is a lack of transparency when it comes to these reviews.

“There is no question that there is oversight. But the question is: What does that oversight consist of? We don’t know that to a large extent. There are these independent people who are supposed to be looking at why people aren’t getting out of cells. But we don’t have any idea of what information they’re getting,” Doob said.

While CSC has criticized aspects of Doob’s and Sprott’s findings, the agency has refused to release any research of its own. Meanwhile, Doob and Sprott’s work was accepted by Minister of Public Safety Bill Blair, and Correctional Investigator Ivan Zinger said it “speaks for itself,” adding that CSC was in “flagrant non-compliance” with the law.

James Bloomfield, the president of the Prairies region for the Union of Canadian Correction Officers, says CSC made a mistake when it changed the policy for solitary confinement overnight, rather than phasing it out more gradually. He believes front-line staff have not been given sufficient direction on how to manage inmates without solitary.

“They didn’t phase it out. The service just decided it was done, period… We’ve been dealing with that decision ever since. We have very concerning, very problematic inmate behaviours and we have no place to isolate them and put them away from the general population,” Bloomfield said.

“We just do our best to work with what we have.”

The arrival of the COVID-19 pandemic complicated matters further. Stony Mountain saw one the worst outbreaks of any federal prison in Canada, with roughly 370 inmates — about half of the incarcerated population — testing positive, including one who died.

Because of the inability to transfer inmates to different facilities during the pandemic, the stays in structured invention units at Stony Mountain have been consistently longer than the 15-day cap, Bloomfield said.

“We’re talking an average, right now, that is quite a bit over what we’re supposed to be. The 15-day mark is what they like to see… Right now, we’re sitting over 100 days.” – James Bloomfield, the president of the Prairies region for the Union of Canadian Correction Officers

“These structured intervention units, as they call it, for that, we now have people staying in there for over 100 days, because we can’t move them around,” he said.

“We end up with a lot more individuals sitting in an SIU for multiple, multiple days. We’re talking an average, right now, that is quite a bit over what we’re supposed to be. The 15-day mark is what they like to see… Right now, we’re sitting over 100 days.”

Last month, Minister Blair went back to parliament to ask for an additional $135 million he said was needed to put an end to solitary confinement in Canadian federal prisons once and for all.

ryan.thorpe@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @rk_thorpe

Ryan Thorpe likes the pace of daily news, the feeling of a broadsheet in his hands and the stress of never-ending deadlines hanging over his head.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.