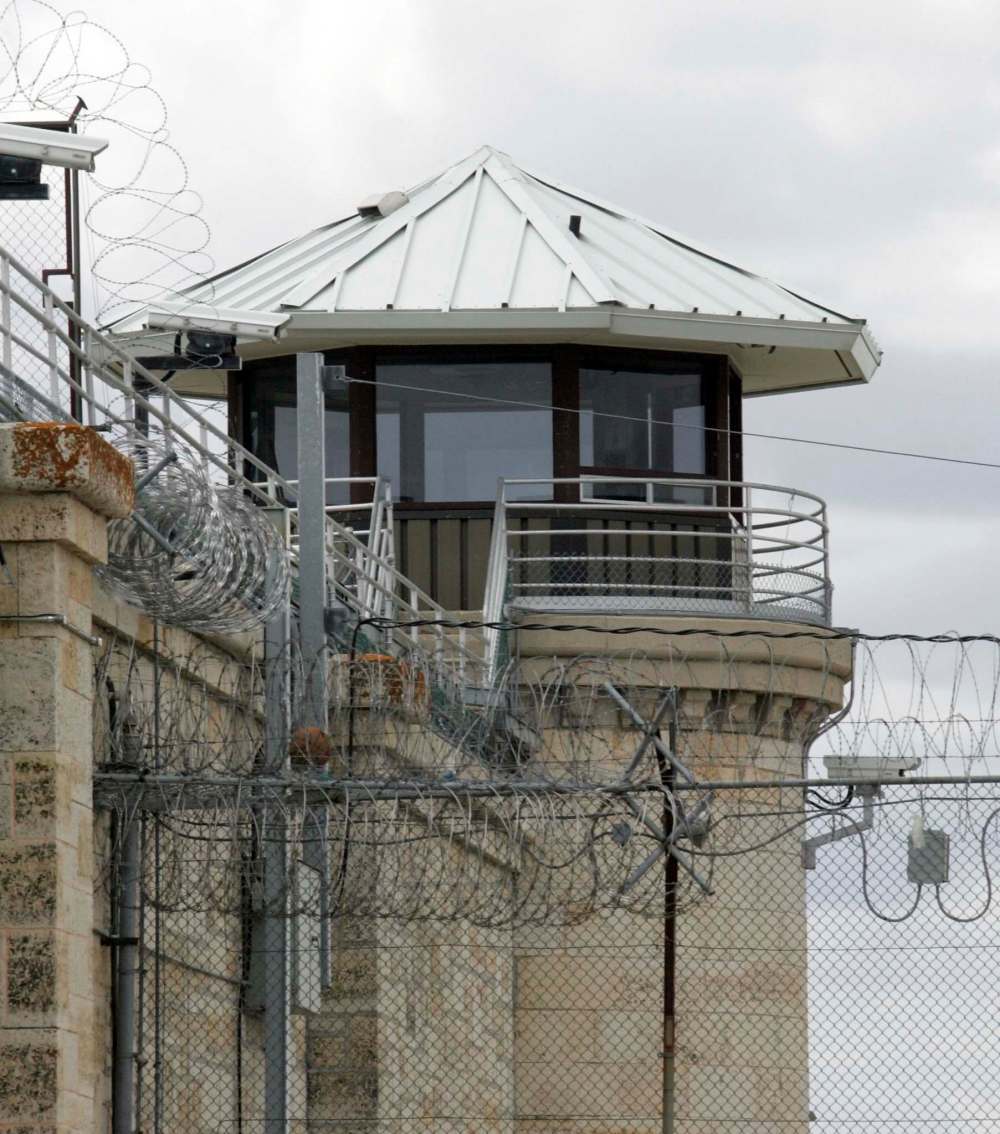

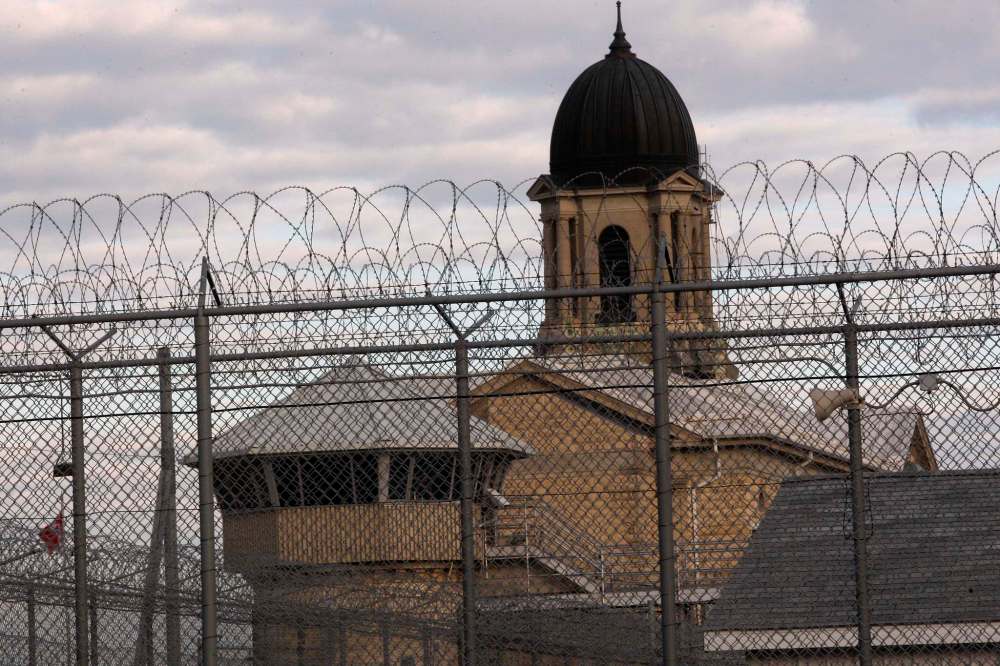

Hard time in hell Gangs are in control, inmates are armed and the threat of violence is omnipresent at Stony Mountain Institution

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 14/05/2021 (1758 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

They call it Murder Mountain.

Every unit of the prison is infested with gangs. Drugs are potent and easy to score. Inmates walk around armed with hidden shanks. Beatings and stabbings are a common occurrence. Homicides follow hangings, and hangings follow homicides.

Dead bodies pile up with disturbing regularity.

Statement from Correctional Services Canada

CSC responds to the Free Press investigation

CSC works with an increasingly diverse and complex offender population, including Security Treat Groups (STG), and has a number of strategies in place to manage and reduce violent incidents in our institutions. We do not tolerate violence of any form and incidences of violence can lead to disciplinary action or criminal charges against those involved

STGs may be defined as any formal or informal ongoing inmate/offender group, gang, organization or association consisting of three or more members. The STG landscape, both in the community and within institutions, is fluid in nature, which makes the identification of groups, members, associates and their compatibilities increasingly difficult to identify and track.

We individually assess each situation and employ interventions at our institutions to promote safety. Each offender undergoes an assessment to find the most appropriate placement, which takes into account any risk factors as well as intervention and rehabilitative needs and the safety and security of the offender and of other offenders and staff… CSC has a policy framework on the management of incompatible offenders, which includes incompatible offenders not residing together and examining incompatibilities prior to a transfer or conditional release.

All STGs who currently reside within the general population at Stony Mountain Institution are compatible with one another and inmates incarcerated in CSC institutions are aware of the dynamics of the STGs. These dynamics are fluid and constantly changing. As such, CSC’s Security Intelligence Officers work closely with provincial and regional counterparts, along with law enforcement partners to stay on top of STG dynamics.

The environment of a correctional institution is challenging and can be unpredictable. When an assault occurs at Stony, CSC contacts the RCMP to investigate and both agencies work collaboratively to examine the incident. Due to the sensitive nature of the investigative process, it is not always possible for CSC to issue a news release immediately following an assault. It is noteworthy that at Stony, in 2020-21, there was a decline overall in assault-related incidents being reported relative to the previous year.

That is the reality of life behind bars at Stony Mountain Institution north of Winnipeg, and while Manitoba’s lone federal penitentiary has long had an infamous and deadly reputation, inside sources tell the Free Press the situation is spiralling out of control.

“With the violence, what you guys out there get told about, it’s probably like 10 per cent of the violence that happens,” one inmate said.

“You really need a weapon to survive in here.”

For the past month, the Free Press has been investigating prison conditions at Stony Mountain, interviewing current and former inmates and guards, academics and advocates, lawyers and watchdogs, and reviewing court transcripts and inquest reports.

The picture that has emerged is of a prison in profound crisis, where guards and inmates alike have been left to navigate the front lines of a deeply dysfunctional institution, and where violence and death lurk around the corners of Stony’s crumbling 143-year-old walls.

Unless decisive action is taken, multiple sources said, the situation will continue to deteriorate.

“It’s getting worse. There are more gangs sprouting up. There are more guys joining the gangs. The way the violence has spiked is proving the gangs are out of control. It’s kind of become the norm and it feels like our management team just accepts that,” one correctional officer said.

“It’s a gang prison. It’s got a name all over Canada as a gang prison. And nothing is really done to separate them anymore…. We have an incident simmering right now between two major gangs and it almost feels like the attitude is, ‘Let’s just wait for it happen and then react.’”

During the past 16 months, Stony Mountain has not just been Canada’s oldest active federal prison, it has also been the deadliest. There have been 13 reported inmate deaths during that time period, and at least 23 dating back to March 2017.

But according to multiple sources, those publicly reported deaths are just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to the violence. The guard said that he believes prison administration isn’t even transparent with Correctional Service of Canada higher-ups.

“In the last few years, I’ve seen a proliferation of violent incidents. It’s a disgrace that the system is not being held accountable. I’ve had many inmates tell me the system is broken, the staff knows it’s broken, and nobody is doing anything about it.” – Criminal defence attorney Martin Glazer

“It’s sort of like a child that doesn’t want to get in trouble with their parents. Stony Mountain has to report incidents to regional headquarters, and then in turn, that gets reported to national headquarters,” the guard said.

“Then the commissioner of corrections is calling here saying, ‘What the f–k is going on at Stony Mountain? Why is it being nicknamed Murder Mountain? So it’s true that a lot of incidents don’t get reported, because they want it to look like everything is running smooth here.”

Martin Glazer, a prominent Winnipeg defence attorney with decades of experience who has handled numerous criminal cases out of Stony Mountain, said that for many years now it has been apparent to anyone paying attention that the crisis is deepening.

“In the last few years, I’ve seen a proliferation of violent incidents. It’s a disgrace that the system is not being held accountable,” Glazer said.

“I’ve had many inmates tell me the system is broken, the staff knows it’s broken, and nobody is doing anything about it.”

When told of Glazer’s comments, one current guard said: “I agree with that 100 per cent.”

“A saying here among COs (correctional officers) is, ‘Well, it is what it is, let’s just get home safe.’ It takes its toll on people. We have a lot of turnover, because the violence has spiked and the suicide has spiked and people don’t want to find a hanger or deal with a guy stabbed 80 times,” the guard said.

“The way… Stony Mountain is right now, you know it’s not going to get better — it’s going to get worse.”

●●●

“To live in prison is to swim with sharks and to walk with tigers. Prisoners live in an atmosphere of high tension and resulting stress. There is the ever-present danger of physical attack. The constant threat of violence is palpable in a penitentiary setting.”

Those are the words of Peter Cory, a former Supreme Court justice who presided over Manitoba’s inquiry into the wrongful conviction of Thomas Sophonow, who was tried three times for the murder of Barbara Stoppel in the early 1980s.

The final report into the Sophonow inquiry was published in September 2001, and in the years since, there has been no shortage of cases at Stony Mountain to illustrate the truth of Cory’s words.

On April 22, 2019, Peter Fisher and Kevin Curtis Edwards murdered Adrian Fillion, 42, in his cell. The two inmates, both of whom were gang-affiliated, targeted Fillion because he was a sex offender.

While Fisher and Edwards were in the cell for just 75 seconds, they managed to stab Fillion — who died in hospital about two hours later — 52 times. Both men pleaded guilty to first-degree murder.

A third inmate, Aaron Michael Ducharme, who was not gang-affiliated, was also charged with murder. Crown attorneys argued that while Ducharme did not stab Fillion, he was the “lynchpin” of the plot and helped cover it up.

The facts in the case were not in dispute: Ducharme admitted to disposing of the bloody shank.

After walking by Fillion’s cell, Ducharme said Fisher threw the shank under the door and told him to get rid of it or he would be next. It was not the first time Ducharme had seen Fisher stab someone, according to court records, and he believed he’d be targeted if he refused.

Manitoba Court of Queen’s Bench Justice Shauna McCarthy agreed, acquitting Ducharme in a Dec. 16, 2020 decision, arguing he could not be held criminally responsible for his actions given the threat of violence that hung over his head.

The threat of violent retaliation “rendered his choice to pick up the shank when ordered to do so effectively involuntary,” McCarthy wrote.

McCarthy’s logic is consistent with what the Free Press heard from multiple sources who all said the unsafe conditions at Stony Mountain often force non-gang-affiliated prisoners into impossible situations.

“There is nowhere safe here right now for somebody who isn’t in a gang and who just wants to do their time. Some guys manage, they come in and somehow stay out of it. I think they probably pay their rent and the gangs leave them alone,” a guard said.

“The only thing they can do is to try to get to minimum-security, try to get over to Rockwood (Institution, adjacent to the main prison). Over there, they can manage. But over here, I don’t like their chances at all. It’s just too infested with gangs.”

In previous years, inmates not affiliated with gangs — as well as sex offenders — were often housed in “Unit 3,” which is known as “protective custody.” That was the one unit of the prison free of gang influence, the guard said.

But that’s no longer an option, he said, because gangs have infiltrated protective custody, as well.

“It’s another aspect of this job that just makes you feel like there’s no solution: the gangs are controlling this place and scaring inmates, a lot of inmates who just want to do their time and get out of here,” he said.

“So now we’ve got protective-custody inmates who say, ‘I’ve got to move.’ Well now you’ve run out of spots to put them. One alternative is hiding them in (the medical wing) for a little bit, but then that takes up a bed from someone else.”

One criminal defence attorney who spoke to the Free Press, but who asked to be quoted anonymously, said numerous clients have told him that “everyone at Stony Mountain is walking around with shanks.”

And the availability of improvised weapons, combined with a “hands-off attitude to violence” and a lack of inmate supervision, creates “tinderbox conditions,” the lawyer said.

On Aug. 16, 2018, Adam Kent Monias, 25, was beaten to death with a baseball bat at Stony Mountain. The day after the assault, RCMP investigators canvassed the area of the prison where it happened and found 43 weapons.

Four inmates were charged in the killing, and at one of the trials, a Stony Mountain security intelligence officer named Miles Day was called to testify. He was cross-examined by lawyer John Rutherford on Feb. 4, 2020.

Asked if it was fair to say that Stony Mountain was a “pretty dangerous place,” Day responded succinctly: “Yes.”

“Do you agree with me that it’s not unusual to find them — to find (weapons) hidden in the institution?” Rutherford asked.

“That’s correct,” Day said.

A guard who spoke to the Free Press on the condition of anonymity was more explicit, saying the 43 improvised weapons found by the RCMP investigators after Monias’ death would be a standard number of shanks to find during any large-scale sweep.

“That wouldn’t be uncommon. If we decided, right now, to go do a massive search, we’d turn up about that many. It’s just a never-ending battle. We’re not getting anywhere when it comes to getting rid of weapons. We’re just walking on a treadmill,” the guard said.

According to the guard, in late April, a large number of inmates affiliated with the Indian Posse and Manitoba Warrior street gangs were in the gym at the same time. The correctional officers on duty got suspicious because they noticed the prisoners were all wearing winter jackets.

“The Manitoba Warriors and the Indian Posse, they’re going to start fighting. It’s just a matter of time. They’re just re-arming now because most of their arsenal was confiscated. But something is simmering.” – Current Stony Mountain Institution guard

“(The guards) went in there to end exercise. They searched them on the way out. They ended up finding 25 weapons. All different kinds of shanks — one guy had something that almost looked like a sword,” the guard said.

“The Manitoba Warriors and the Indian Posse, they’re going to start fighting. It’s just a matter of time. They’re just re-arming now because most of their arsenal was confiscated. But something is simmering.”

While the inmates who spoke to the Free Press declined to comment on gang tensions at the prison, one of them said that most of the violence is the result of “incompatibles” — rival gang members — being housed together.

That’s consistent with what the guard said, arguing that in recent years — due to the increase in gang members locked up at the facility — prison officials have effectively given up on keeping rivals separated.

“Every one of the murders that I can think of, they were gang-related. It’s not like two inmates had a disagreement in the gym and a fight went too far and someone ended up dead. It’s all gang stuff — all of it,” the guard said.

“The gangs are overflowing so much that there are only so many places for these guys…. If something happens in the medium (security), it always spills over into the max. If something happens in the max, it spills over into the medium.”

In 2020, two lawsuits were filed against the Correctional Service of Canada by former Stony Mountain inmates who alleged they were knowingly housed with incompatibles, and that the safety concerns they raised to staff were either ignored or not acted upon.

On April 17, 2020, Dallas Friesen — an ex-member of the Rock Machine biker gang — filed a lawsuit alleging he was the victim of a vicious beating shortly after arriving at Stony Mountain in 2018 because staff ignored his safety concerns.

“This is what happens to Rock Machine when they come to Stony,” one of his attackers reportedly said during the beating, according to the lawsuit.

Two months later, Jeffrey Rodgers — who was beaten and stabbed in his cell — filed a similar statement of claim, alleging staff ignored his concerns about incompatibles.

The lawsuits remain before the courts, and CSC has filed statements of defence in both cases denying any wrongdoing or liability.

One inmate who spoke to the Free Press said he believes nearly all the violence at the prison is the result of “putting incompatibles with incompatibles.”

“A lot of the things that have happened here, or a lot of the violence that has happened, it’s from them putting incompatibles together. It’s guys who shouldn’t be together. I don’t know if it’s conscious, but if it’s not conscious, it’s laziness,” the inmate said.

“They just don’t really care, you know? They put incompatibles together with people they shouldn’t all the time.”

●●●

While the violence at Stony Mountain has been getting worse in recent years, killings at the prison are nothing new.

In June 2016, provincial judge Brent Stewart issued his final report for the dual inquest into the deaths of inmates David Durval Tavares and Sheldon Anthony McKay.

In March 2005, Tavares, a high-ranking member of the Native Syndicate, was beaten to death by fellow gang members as punishment for breaching their code of conduct.

In May 2006, McKay, the head of the Indian Posse at Stony Mountain, was strangled to death in his cell by other members of the gang in a leadership coup.

“It is clear, as one would suspect, that the street gang mentality controls most if not all of the daily happenings of a prison system in Western Canada. Specifically, we have heard evidence that SMI houses more gang members than any other federal prison in Canada,” Stewart wrote.

“As a result, it is little wonder that in specific units within the prison itself, a siege mentality exists.”

The most recent inquest into a homicide at Stony Mountain was held in December 2019, which examined the 2017 killing of Lewis Sitar, who was beaten to death in his cell after being falsely labelled a sex offender.

Inmates Carl Jesse Klyne and Tristan Storm Fisher pleaded guilty to manslaughter in the case.

“There is no doubt that the prison population in SMI has become increasingly more complex. There are a growing number of security threat groups or gangs requiring isolation from one another to prevent violence,” associate chief provincial court Judge Tracey Lord wrote.

Lord noted that the prison built in 1877 poses significant safety challenges due to a lack of space and the existence of larger pods that house greater numbers of inmates together.

Stony Mountain’s infrastructure has long been identified as a cause for concern. It was a significant factor in the spread of COVID-19 (half of the inmates were infected) and has also contributed to the high percentage of suicides by hanging.

“The conditions in the medium (security area) are worse than the conditions in the max…. In the medium, the cells are falling apart, the walls are falling apart, the floors are falling apart. There are bars instead of doors. There’s no privacy,” one inmate said.

“It’s all falling apart. It’s, like, a 145-year-old building or whatever. It’s not well maintained…. I swear there’s black mould in there,” another inmate said.

“The conditions in the medium (security area) are worse than the conditions in the max…. In the medium, the cells are falling apart, the walls are falling apart, the floors are falling apart. There are bars instead of doors. There’s no privacy.” – Current Stony Mountain Institution inmate

The guard who spoke to the Free Press echoed those sentiments, saying “the place is basically starting to fall apart,” and that they have contractors at the prison every day “patching things up.”

“Our door system isn’t working properly right now. Sometimes you can’t get the inmate out of their cells and have to call a contractor. A lot of them will say, ‘It can never be fixed.’ They just have to Band-Aid the place up as best they can,” the guard said.

“It’s like a dungeon. It’s dingy. It’s gross.”

CSC has long been resistant to demands for change — particularly from the Office of the Correctional Investigator, the federal prison ombudsman. The office has issued multiple reports into the agency’s shortcomings dating back decades.

In October 2020, Correctional Investigator Ivan Zinger tabled the office’s latest annual report in Parliament.

“I am deeply disappointed by the (Correctional) Service and Government’s responses to my latest annual report. Most recommendations are met with vague and future commitments to review, reassess, or even, in the case of sexual violence in prisons, redo the work that my office has already completed,” Zinger said.

Martin Glazer, the Winnipeg-based defence attorney, said he believes there needs to be an external oversight body created for CSC operations with more teeth than Zinger’s office, armed with the authority to do more than make non-binding recommendations.

“Inmates have the right to live. When they’re sentenced, it’s one thing to lose your liberty, but to lose your life because there’s a lack of intervention or supervision or accountability, it’s just a terrible thing,” Glazer said.

“There should be an investigation into the Correctional Service of Canada to expose the inadequacies and shortcomings at the Stony Mountain penitentiary. And that has to be a full-blown investigation, no holds barred, to get to the root of the problem.”

And the prison is failing in its responsibilities, under Canada’s general sentencing principles, to stem recidivism rates and improve public safety in the long term, the guard said.

“It’s not rehabilitating anybody,” he said.

“It’s making things worse.”

ryan.thorpe@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: rk_thorpe