Serving deadly time Manitoba's ancient, inadequate Stony Mountain Institution has the worst inmate fatality rate of any federal prison in Canada

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 23/04/2021 (1695 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

IT HAS BEEN 59 years since the Canadian state last slipped a noose around the neck of a prisoner, and more than four decades since the gallows were formally abolished in this country, yet death continues to lurk behind the bars of Stony Mountain Institution north of Winnipeg.

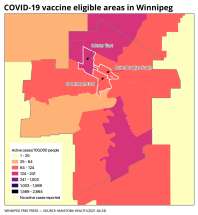

Deaths at Stony from March 2017 to present

(The provincial government introduced Bill 16 that month, which no longer required mandatory inquests for deaths of inmates)

Lewis Sitar, 50 – March 3, 2017 (Inquest called)

Lawrence McMahon, 40 – April 1, 2017

Max Richard, 43 – Jan. 7, 2018

Adam Monias, 25 – Aug. 18, 2018

Nolan Thomas, 26 – Nov. 2, 2018

Timothy Koltusky, 34 – March 12, 2019

Michael Monney, 27 – April 12, 2019

Adrian Fillion, 42 – April 22, 2019

Tyson Roulette, 34 – Dec. 8, 2019 (Inquest called)

Shawn Poitra, 29 – Jan. 5, 2020

Adrian Young, 39 – March 7, 2020

Patrick Eaglestick, 25 – March 24, 2020

Farron Rowan, 32 – April 26, 2020

Kurt Harper, age not released – May 17, 2020

Roger Jackson, 70 – Sept. 3, 2020

Melvis Owen, age not released – Dec. 15, 2020

Inmate unknown, COVID-19 death – Dec. 28, 2020

Tommy Beaulieu, 23 – Jan. 11, 2021

Hardisty Ballantyne, 44 – Feb. 1, 2021

Bruce Kaiser, age not released – Feb. 17, 2021

Dwayne Simard, 37 – March 1, 2021

Kenneth McDougall, age not released – April 3, 2021

Stony Mountain is not just the oldest active federal prison in Canada — it is also the deadliest.

In the past 15 months, 13 inmates have died there; no other federal prison has reported more deaths during that period.

Five people died in the first 93 days of 2021 alone, an average of one every 18 days. It was during one of the worst outbreaks of COVID-19 at a federal correctional institution in Canada; half of Stony’s inmates were infected.

In the past four years, 23 inmate deaths have been reported, based on a Free Press review of publicly available notifications issued by Correctional Services Canada. The deaths were caused by suicide, drug overdose, gang violence and “apparent natural causes.”

But the details in those cases — including what happened and why, and whether any steps were taken by CSC to prevent future such deaths — remain shrouded in mystery, in part due to a 2017 change to Manitoba’s Fatality Inquiries Act ushered in by the Pallister government.

As a result, inquests are no longer mandatory for deaths that occur behind bars in Manitoba. Instead, it is now at the sole discretion of the chief medical examiner — a health professional with no legal training — whether an inquest will be held in such cases.

If an inquest is not called — as has happened with many deaths at Stony Mountain — the only review, aside from potential criminal probes, is an internal investigation conducted by CSC itself.

The outcomes of those investigations are often not shared with the family of the deceased, let alone the media or public. It is a status quo that brings to mind the antiquated idea that police officers should be left to police themselves when accusations of wrongdoing arise.

The situation is made all the more troubling by the soaring rate of Indigenous incarceration at Stony Mountain and elsewhere in the country, as noted in a report by the Office of the Correctional Investigator, Canada’s federal prison ombudsman.

The ongoing “Indigenization” of prisons has led some critics to call them the “new residential schools.”

“As for Stony, I am concerned it is a penitentiary with an inordinate number of deaths…. It’s also a penitentiary that is about 70 per cent Indigenous,” Ivan Zinger, the correctional investigator, tells the Free Press.

“I’m also concerned about the infrastructure…. The old medium-security part of it is over 100 years old. It still has those open bars with no windows. This is why COVID was able to spread so quickly.”

All told, the virus infected 371 inmates, killing one.

Welcome to Stony Mountain Institution: where a prison sentence far too often ends in a death sentence, and where transparency is the only thing successfully kept under lock and key.

ON JULY 25, 1871, Anishinaabe and Swampy Cree nation chiefs gathered with British Crown representatives at Lower Fort Garry to negotiate the signing of Treaty No. 1, the first agreement between the fledgling Canadian state and First Nations leadership.

At the start of the meeting, the Indigenous leaders told the Hon. Adams George Archibald — a Father of Canadian Confederation and the first lieutenant-governor of Manitoba — there was a “cloud before them which made things dark.”

The negotiations could not begin, the chiefs said, until the cloud was “dispersed.”

“On enquiring into their meaning, I found that they were referring to some four of their number who were prisoners in gaol. It seemed that some Swampy Indians had entered into a contract with the Hudson’s Bay Company as boatmen, and had deserted,” Archibald later wrote.

The (treaty) negotiations could not begin, the chiefs said, until the cloud was “dispersed.”

“A few of the offenders had paid their fines, but there were still four Indians remaining in prison.”

It would be six years before Stony Mountain opened in the fall of 1877 and already incarceration had become a central, defining feature of the relationship between settlers and Indigenous peoples.

Today, the prison stands — as it has for the past 143 years — roughly 24 kilometres north of Manitoba’s capital, situated on a prominent limestone outcrop that rises above the surrounding prairie landscape.

The prison was built near the spot a British expeditionary force was stationed during the quelling of the Red River Resistance of 1869-70 — the Métis revolt led by Louis Riel, who was executed for treason only to be declared a founder of Manitoba in death.

On most days, a Canadian flag can be seen fluttering in the wind in the parking lot of the sprawling prison compound, with its medium- and maximum-security wings stationed across the imposing, fenced-in grounds. The words “Manitoba Penitentiary” — the name it operated under until 1972 — are etched into the stone façade above the front doors.

According to the federal government’s website, Stony Mountain has a “rated capacity” of 546 prisoners, but overcrowding is common. In January, during the COVID-19 outbreak, it was reported there were 744 inmates.

In its early days, Stony was seen by settler contemporaries as symbolizing their successful push into previously “wild” frontiers, says academic Seth Adema, who wrote a PhD thesis on the history of Canadian prisons for Wilfrid Laurier University in 2016.

And it did not take long for that symbol to become a reality for Indigenous peoples, many of whom soon found themselves locked up in its cells. In recent years, the situation has spiralled out of control, with incarceration rates for First Nations people spiking at the same time historical crime rates have fallen.

Of the more than 12,500 inmates in federal prison in Canada, nearly one-third are Indigenous. The situation is far worse in Manitoba and Saskatchewan, where it’s closer to 75 per cent.

Indigenous peoples, meanwhile, make up roughly five per cent of the overall population. It is impossible to understand their overrepresentation among inmates without situating the development of prisons in the context of Canada’s colonial past.

Among the early inmates at Stony Mountain were chiefs Big Bear and Poundmaker, who had been convicted of felony treason for their roles in the 1885 North-West Rebellion. Chief Poundmaker was released after seven months due to health concerns, and he died at the age of 44 shortly after being set free.

Chief Big Bear served two years and was also released due to failing health. He died soon after at the age of 62. Contemporary scholars agree that harsh prison conditions likely contributed to their untimely deaths.

The first warden was Samuel Bedson, a military man who settled in Manitoba after the Red River Resistance. According to Adema — whose thesis had a chapter devoted to the early years at Stony Mountain — Bedson made the “colonialism of the penitentiary explicit.”

…The inspector determined it was in “shamefully defective condition,” reporting back to his superiors that it was “difficult to conceive” of a facility “more unsuited” to its stated purpose.

Shortly after its opening, the new warden began complaining about the poor conditions there. In 1879, Bedson was bedridden for three months due to typhoid fever, which he attributed to defective drainage at the prison.

Eventually, he convinced the federal penitentiary inspector to visit, and when he did, the inspector determined it was in “shamefully defective condition,” reporting back to his superiors that it was “difficult to conceive” of a facility “more unsuited” to its stated purpose.

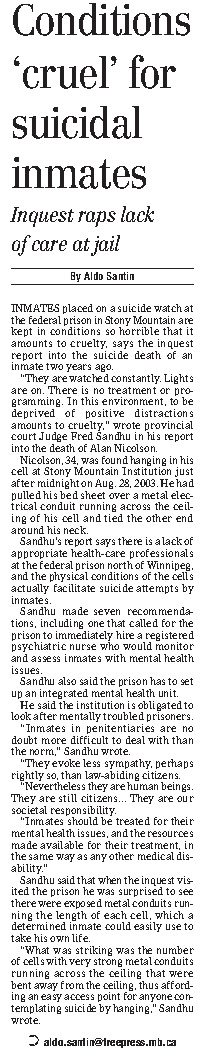

Despite the early warnings, the old medium-security wing of the prison remains in operation. People continue to get sick and die, and some — such as Alan Nicolson — die by suicides that Manitoba judges have repeatedly ruled preventable.

IT WAS SOMETIME around midnight, on Aug. 29, 2003, inside cell A6-18 at Stony Mountain, that the sad, short life of Alan Nicolson came to an end. The 34-year-old was a first-time federal inmate serving a 50-month sentence for robbery. He had been in prison for 37 days.

Earlier that year, while in the throes of a narcotics binge, Nicolson wrapped a white T-shirt around his face and stormed a Winnipeg convenience store with a knife. He stole $23 and a few packs of cigarettes before he ran. Minutes later, he was spotted by police and arrested.

Although no one was hurt, it was not Nicolson’s first run-in with the law, and he was sentenced to more than four years.

Nicolson did not have a white T-shirt at his disposal in his cell at Stony, but he had a blue bed sheet. And rather than tying it around his face to conceal his identity, he wrapped it tight around his neck to cut off the flow of oxygen to his brain.

About 30 minutes later, guards found him hanging from a makeshift noose tied to an electrical fixture on the ceiling in his cell. They cut him down and dragged his limp body into the hallway to begin CPR, but it was too late.

A suicide note was found slipped into the pages of a Bible in his cell.

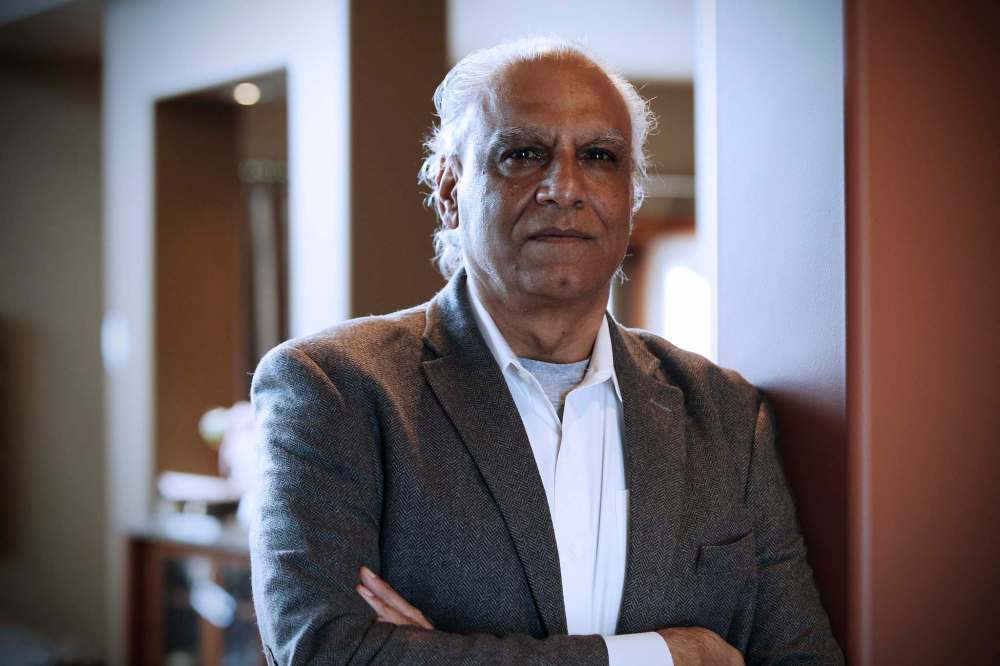

Two years later, provincial court Judge Fred Sandhu finalized an inquest report into Nicolson’s death. At the time, inquests were mandatory whenever an inmate died in Manitoba. The aim was not to assign guilt, but to learn lessons that could prevent future deaths.

It was not the first time Sandhu had presided over an inquest into an inmate suicide at Stony Mountain. Three weeks earlier, he’d issued a report into the death of Richard Lagimodiere, 32, a paranoid schizophrenic who hanged himself in his cell 60 days before Nicolson did.

The two reports exposed deep flaws in Stony Mountain’s ability to treat inmates suffering from severe mental illness. After presiding over both inquests, Sandhu concluded the lack of mental-health supports at the prison bordered on “gross institutional misconduct.”

Nicolson’s death was emblematic of many issues at the prison. For example, when he was jailed there, the staff did not request his medical records, so the true extent of his illness wasn’t known.

When Nicolson asked for Ritalin, the staff accused him of drug-seeking behaviour, since the medication can be used recreationally. What they didn’t know was Nicolson had been diagnosed with attention deficit disorder and previously prescribed the drug, which had a positive effect.

And when Nicolson told the staff he was hearing voices, his episodes were dismissed as “clearly manipulative and exaggerated” not just by the guards and nurses, but also by the psychiatrist responsible for his medications.

Had the prison requested his medical records, staff would have known that Nicolson had been diagnosed with schizophrenia more than a decade earlier.

In the weeks leading up to his death, Nicolson slashed his left wrist several times and repeatedly told prison staff he was suicidal. The staff dismissed his self-harm as “attention-seeking,” rather than a true attempt to end his life.

But the issues at Stony were not limited to bureaucratic incompetence. One witness at the inquest was Jon Nemeth, a fellow inmate who spent time in a cell next to Nicolson on the mental-health ward.

Under oath, Nemeth alleged that during an argument shortly before he died, a guard told Nicolson to kill himself. The guard denied the accusation, but Nemeth was backed up at the inquest by Nicolson’s father, who said his son had reported the encounter to him during a phone call.

Prison staff would repeatedly testify to the critical shortage of mental-health resources at the prison. The mental-health ward, they said, was a misnomer and offered no extra supportive services.

Sandhu determined there were virtually no mental-health supports available, despite the fact many inmates had been diagnosed with severe psychiatric illnesses.

“Inmates in penitentiaries are no doubt more difficult to deal with than the norm. They evoke less sympathy, perhaps rightly so, than law-abiding citizens. Thus, they are not high on the list of governmental priorities in the allocation of fiscal resources,” Sandhu wrote in his 2005 report.

“Nevertheless, they are human beings. They are still citizens. We as a society, have decided to punish them by absolute confinement. They are our societal responsibility. As we must house and feed them, so too must we take care of their medical needs.”

“Nevertheless, they are human beings. They are still citizens. We as a society, have decided to punish them by absolute confinement. They are our societal responsibility. As we must house and feed them, so too must we take care of their medical needs.”

He made 11 recommendations following the Lagimodiere and Nicolson inquests. In particular, he pointed to the desperate need to increase staffing levels in the psychiatric department, which had decreased in recent years due to budget constraints.

He also recommended the electrical fixtures on the ceilings of cells — which Nicolson had used to kill himself — be retrofitted to prevent their use as “fixed points for hanging.”

Bruce Cameron, the prison’s head of engineering, had testified it would be possible to make the change. That was in 2005. But in the years to come, CSC failed to implement the recommendation and the bodies kept piling up.

In June 2006, Grant Ermine, 23, hanged himself. As did Devon Newson, 18, the following month. Both men tied their nooses to electrical fixtures on the ceiling in their cells.

At the subsequent inquests, the presiding judges pointed to Sandhu’s earlier recommendation to retrofit the fixtures. Yet again, the judges told CSC to make the change.

The federal department did not, and as a result it happened again.

Dwayne Flett, 32, was a schizophrenic with the cognitive functioning of a “five to 10-year-old child.” Court records show the sentencing judge was unaware of his cognitive limitations when he sentenced him to five years behind bars for his first criminal conviction.

He hanged himself in solitary confinement at Stony Mountain in April 2015. Like the others, he tied his makeshift noose to the electrical fixture on the ceiling.

Just hours before he killed himself, Flett told a guard he was feeling suicidal. Rather than transfer him to suicide watch — as mandated by CSC policy — the guard left him in his cell. At the inquest, a CSC official said the guard in question had been “spoken to” about the policy breach.

“It seems like criminal negligence, doesn’t it?” says Catherine Latimer, the national executive director of the John Howard Society.

“They just don’t care…. Prisoners are a non-sympathetic group. I keep thinking that if you were treating animals the way you’re treating prisoners there would be this great human cry.”

IN THE PAST 15 years, there have been seven inquests into hanging deaths at Stony Mountain, and five others into inmate suicides at Manitoba provincial jails and psychiatric facilities. Three of the latter cases involved 15-, 16- and 17-year-old youths.

Last month, Manitoba’s chief medical examiner called an inquest into the death of Tyson Roulette, 34, who hanged himself at Stony Mountain in December 2019; it’s not clear at this point whether Roulette hanged himself from an electrical fixture in his cell.

Suicide has long been a major concern in Canadian prisons, and there have been no shortage of recommendations over the years — from provincial judges to independent advocates to federal ombudsmen — as to what CSC could do to improve the situation.

Nonetheless, the deaths have continued, with little evidence to suggest CSC has materially improved its ability to keep inmates safe and alive.

“As a matter of immediate priority, CSC should remove all known suspension points in segregation cells across the country. Where this is deemed technically or economically unfeasible, such cells (or ranges) should be decommissioned.”

From 1993-2017, at least 242 inmates killed themselves in Canadian federal prisons, an average of 10 per year, a trend line that has stayed notably flat over time. Between 15 and 20 per cent of all in-custody deaths are suicides, hanging the most common method.

The suicide rate in federal prisons — much like the rate of mental illness — is significantly higher than in the general population. Some estimates suggest federal prisoners are seven times more likely to kill themselves than the average Canadian.

Due to a lack of transparency in federal prisons, the Office of the Correctional Investigator published a systematic report into in-custody deaths in 2014. The OCI found that many of the issues identified during repeated inquests in Manitoba — such as easily accessible suspension points in cells — had long been highlighted as causes for concern across the country.

“Known suspension points have not even been removed from segregation cells, the most vulnerable area of the prison where a disproportionate number of inmates attempt and complete acts of suicide,” the OCI wrote.

“As a matter of immediate priority, CSC should remove all known suspension points in segregation cells across the country. Where this is deemed technically or economically unfeasible, such cells (or ranges) should be decommissioned.”

“When a convict/inmate commits suicide invariably a cynical guard will mutter… ‘We rehabilitated that one– he won’t be back,’ ” (former assistant warden Williams) Edwards wrote.

Seven months after that report was released, Dwayne Flett hanged himself from an electrical fixture on the ceiling of his solitary-confinement cell at Stony Mountain. The OCI says that known suspension points remain a concern in federal prisons to this day.

“At the end of the day, just like any ombudsman, I only have the power to make recommendations, and my recommendations are non-binding on the Correctional Services or the minister (of public safety) or the government of Canada,” Zinger says.

“The suspension points. We’ve raised that issue in several reports.… This is something that is an easy fix and they can’t even get those ones correct.”

For Stony, the story of inmate suicide is a story of institutional indifference to death.

In his 2004 book, Stony: A History of Manitoba Penitentiary, William Edwards — a former assistant warden at the prison who interviewed dozens of correctional officers for the book — captured the attitude some guards have long held when inmates kill themselves.

“When a convict/inmate commits suicide invariably a cynical guard will mutter… ‘We rehabilitated that one — he won’t be back,’ ” Edwards wrote.

When an inmate dies in federal prison, CSC is quick to issue a death notification to the public — often within 24 to 48 hours.

But the details released are limited and sporadic. In some cases, officials will report the inmate’s age and criminal offence — which has raised the eyebrow of the correctional investigator, who has publicly asked what relevance the inmate’s conviction has to their death.

In cases where violence, suicide or drug overdose aren’t suspected, CSC reports the inmate died of “apparent natural causes,” but no additional information is released following an autopsy. And if the inmate did die suddenly or prematurely, CSC makes no mention of the cause or manner of death.

According to the OCI, it’s often difficult for the grieving families of the deceased to get information about what happened to their loved one. In some cases, families have been forced to file access-to-information requests and pay processing fees in their search for answers.

And as bad as transparency and oversight is with regards to CSC Canada-wide, the situation at Stony Mountain has deteriorated under the current provincial government. While the prison is under federal jurisdiction, for decades provincial inquests gave Manitoba judges the opportunity to push for potentially life-saving changes at the facility.

In 1990, the Fatality Inquires Act went into effect in Manitoba, establishing rules for when inquests would be held. For example, if police killed someone, or an inmate died behind bars, the legislation stipulated that inquests would be mandatory.

But in March 2017, then-justice minister Heather Stefanson tabled an amendment to the act, Bill 16, which proposed removing mandatory inquests in a majority of cases other than when police officers kill someone in the line of duty.

While inquests would remain presumptive under the new rules, Bill 16 would give the chief medical examiner the authority not to call one if they considered it unnecessary. The Tories justified the move by arguing that legal experts had long raised concerns the legislation was broken and in need of reform.

Critics of Bill 16 agreed the legislation required improvements, but said granting sole authority to the medical examiner — a health professional with no legal training — to determine the necessity of an inquest was a bad idea.

The bill received significant opposition at the legislature from both the NDP and the Liberals. It was also criticized by private citizens including human-rights attorney Corey Shefman and John Hutton, the former head of the Manitoba chapter of the John Howard Society. Even former chief medical examiner Dr. Peter Markesteyn said Bill 16 would result in undue political pressure on the office.

In an op-ed published in the Free Press in March 2017, Shefman wrote the provincial government seemed more concerned with “saving money” than “enhancing justice.”

“The government’s clear aim with Bill 16 is to reduce the number of inquests conducted. In doing so, they express a clear bias against the victims whose deaths are to be investigated and the families of those victims,” he wrote.

“The government of Manitoba’s theft of victims’ stories, and appropriation of the sole right to tell the definitive and official version of those stories, is an exercise of power against which the victims are unable to defend.”

If passed, Shefman argued, the bill would harm the families of people who died behind bars, reduce oversight and accountability in prisons, and erode the ability of provincial court judges to push for policy changes that could save lives.

It is a position he maintains to this day.

Despite significant opposition, Bill 16 went into effect in November 2017. Since then, Manitoba’s chief medical examiner has called just two inquests into inmate deaths at the prison.

Despite significant opposition, Bill 16 went into effect in November 2017. Since then, Manitoba’s chief medical examiner has called just two inquests into inmate deaths at the prison.

The first was for Lewis Sitar, 50, who was beaten to death by fellow inmates in March 2017 after being falsely labelled a sex offender. The second was announced last month into Roulette’s December 2019 hanging death.

In the 33 months between the Sitar’s killing and Roulette’s suicide, at least seven other inmates died at Stony Mountain, but there were no inquests called. As predicted by Bill 16 critics, the changes have resulted in fewer inquests and less insight into prison conditions.

“I’m concerned about some of the provinces that don’t have mandatory inquests,” Zinger tells the Free Press.

“I’m concerned because the only accountability becomes an internal investigation by the agency that is looking at themselves, which is never good.”

“I’m concerned because the only accountability becomes an internal investigation by the agency that is looking at themselves, which is never good.”

In 2018, the Manitoba Law Journal published an article by Nichole Mirwaldt that recounted the battle over Bill 16 and analyzed how the new inquest system in Manitoba compares to other provinces.

Mirwaldt found that Manitoba is the only jurisdiction in Canada to grant sole authority on inquests to the chief medical examiner without a formal appeals process. As a result, the mechanisms of accountability are weaker here than anywhere else in the country.

And that lack of accountability, as well as concerns over racism in the Canadian criminal justice system, are reasons why Arlen Dumas, the Grand Chief of the Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs, believes a new, independent oversight body is needed. He points to the Independent Investigation Unit of Manitoba — the provincial police watchdog — as a potential model, but stresses it is critical to properly support and staff the agency so it can be successful.

“There needs to be more oversight… It shouldn’t take conflict or a negative instance to continue to force change. We need to take these mechanisms, these systems that we’ve developed through innovation, and continue to hone them so they can play the role they’re truly intended to play,” Dumas says.

“The political will and the wherewithal just needs to be put in place.”

Dumas says there needs to be a rethinking of the criminal justice system, with greater focus on, and resources devoted to, restorative justice, rather than simply punishing people who step outside the law. He adds that our current systems are archaic and do little to rehabilitate people.

And on one point, Dumas is unequivocal: Stony Mountain Institution should be shuttered.

“You take a look at Stony Mountain and that institution itself is archaic. It was built over 100 years ago… The floor plans, the layout, everything is back in that date. They should shut it down,” Dumas says.

“All these archaic and systemically racist processes continue to perpetuate. It’s like (Aboriginal Justice Inquiry of Manitoba co-chair) Justice Murray Sinclair said: ‘You can get rid of all the racists tomorrow, but the system will still perpetuate.’ You got to change that system.”

NEARLY A CENTURY ago, Agnes Macphail — the first woman elected to Parliament in Canadian history and a notable prison reformer — said the conditions at Stony Mountain were “dangerous and unfit for habitation.”

And while a new maximum-security wing was built in 2014, many inmates are still housed in cells that are more than a century old, constructed at a time when the lashing and paddling of prisoners was still considered an appropriate punishment.

But the outdated infrastructure isn’t just a concern for the inmates, it’s also a concern for the guards, says James Bloomfield, the president of the Union of Canadian Correctional Officers’ Prairies division.

During the pandemic, Bloomfield says, COVID-19 was able to take advantage of the aging infrastructure at the prison, which put his members — and, by extension, their families — at increased risk of catching the deadly virus.

“We try to create the best environment we can with very limited resources. The stressors on staff are unbelievable right now. We’re working in a congregate-living environment where people have been at high, high risk,” he says.

“You have an open-bar scenario with 50 or 60 people living in one open room. It’s very difficult to control the airflow. (Stony Mountain is) just not designed for a situation like this.”

Corrections responds

The Free Press requested an interview with the warden of Stony Mountain Institution, as well as a federal spokesperson for Correctional Services Canada, for this story. Those interview requests were denied. Instead, CSC responded with a written statement, which has been edited for clarity.

● COVID-19 response

The health and safety of employees, inmates and the public remain a top priority for the Correctional Service of Canada. CSC works closely with local public health authorities, unions, the Public Health Agency Canada, the Canadian Red Cross and other stakeholders to prevent and mitigate the spread of COVID-19. We have dedicated health services in our institutions, including testing and tracing capacity to identify and treat inmates who are diagnosed with the virus.

The Free Press requested an interview with the warden of Stony Mountain Institution, as well as a federal spokesperson for Correctional Services Canada, for this story. Those interview requests were denied. Instead, CSC responded with a written statement, which has been edited for clarity.

● COVID-19 response

The health and safety of employees, inmates and the public remain a top priority for the Correctional Service of Canada. CSC works closely with local public health authorities, unions, the Public Health Agency Canada, the Canadian Red Cross and other stakeholders to prevent and mitigate the spread of COVID-19. We have dedicated health services in our institutions, including testing and tracing capacity to identify and treat inmates who are diagnosed with the virus.

Since the beginning of the pandemic, Stony Mountain Institution has adapted and learned a great deal about the challenges of preventing and containing the COVID-19 virus. Early on, all institutions put in place measures including mandatory masks for inmates and staff, physical distancing, health screening of anyone entering institutions, increased and enhanced cleaning and disinfection at sites, infection prevention and control reviews as well as significant testing among inmates and staff, including those who are asymptomatic.

In late 2020, researchers from the National Microbiology Laboratory, Health Canada and the Winnipeg Regional Health Authority collected air and surface samples at Stony. This effort identified how the COVID-19 virus was

spreading at Stony, what measures we had put in place that were being effective in preventing the spread and what measures could be strengthened. There have been no positive cases of COVID-19 at Stony since the end of the outbreak and we remain diligent in adhering to our extensive infection prevention and control measures.

CSC is currently rolling out the second phase of its vaccination strategy. All federal inmates and staff who work in correctional institutions are being offered the Moderna vaccine. This will help further protect those in our care and custody and the employees who work in these congregate living settings.

● Mental health

CSC continues to provide every inmate with essential health services, including mental health provided by qualified mental health professionals. Effective and timely intervention in addressing the mental health needs of offenders is a priority, with a focus on prevention. All inmates are screened for suicide risk within 24 hours of their arrival at an institution and screening also occurs throughout an offender’s sentence. Enhancing prevention and intervention for offenders with suicidal behaviours is a continuous goal.

CSC has an integrated mental health strategy and delivery model to ensure essential services match the needs of the offender population. Staff, including correctional officers, are provided with suicide and self-injury intervention training and continuous development, and are trained to respond immediately to preserve life and prevent bodily harm. Health staff are provided with specialized training and continuous development on suicide and self-injury assessment and intervention.

Whenever a person dies in federal custody, the police and coroner or medical examiner are notified. If the death appears to be of natural causes, CSC conducts a quality of care review. In circumstances in which the coroner or medical examiner investigate the cause of death, CSC provides complete support to such investigations as they can provide an opportunity for us to improve the way we manage inmates under our care and custody and to enhance relevant prevention and intervention strategies.

● Infrastructure at Stony

CSC continually evaluates infrastructure requirements based on a number of priorities to ensure it can meet its mandate, ensuring health and safety considerations and availability of financial resources through a national five-year program of work. The program of work is reviewed and updated annually to accommodate revised priorities and unanticipated requirements. CSC has taken measures to monitor and evaluate the existing infrastructure at Stony and continues to prioritize funding for the replacement of essential life safety systems and structural repairs to ensure the safe operation of facilities for both staff and offenders.

In an effort to mitigate the spread of the virus, Bloomfield says guards have been forced to keep inmates isolated as much as possible, which means less time spent outside of cells. But that comes with drawbacks, he adds, such as increased stress among the inmates.

“In an environment of stress like that, where you have reduced movement and intermixing, we have less inmate-on-inmate violence because there is less opportunity for that. But when you have more stress and restrictions, that’s when you generally see more self-harm and suicide,” Bloomfield says.

“We do always have a lot of violence at (Stony Mountain). The mixture of inmates, the population we have at that site, it’s just a younger, more violent, gang-ridden population… But everything has been reduced with the reduced movement during COVID.”

Zilla Jones, a criminal defence attorney in Winnipeg who has worked with many clients sentenced to serve time at Stony Mountain, says the shocking conditions are evident from the time you step inside.

“In the summer, it will be hot, hot, hot, hot. You can barely breathe. You’ll be taking off your jacket and still sweating. In the winter, in January, the guards will warn you, ‘Keep your gloves on. Keep your coat on.’ And you get in there and it’s just drafty and super cold,” Jones says.

But more concerning than the aging infrastructure and poor temperature controls, Jones says, are the general conditions that include high levels of gang activity, a “rampant” drug trade, frequent violence and a dearth of mental-health supports.

“There is a real feeling when my clients get in there that it’s the Wild West.… One guy described it to me as ‘eat or be eaten’… kill or be killed.

“Stony Mountain actively makes people worse.”

That sentiment was echoed by Fred Sandhu, the former provincial court judge who oversaw three inquests into inmate suicides. During his career on the bench, Sandhu also sentenced numerous people to time inside the prison.

“What good are recommendations if implementation can just be cast aside with impunity?”

Like Jones, Sandhu believes Stony Mountain does little to reduce re-offending rates, arguing inmates often leave worse than when they arrived. And given that most inmates will one day be released back into the community, Sandhu asks why more isn’t done to rehabilitate them in the name of public safety.

“At the end of the day, I think it comes down to cost,” he says.

Back in 2005, Sandhu was the first judge to recommend Stony retrofit the electrical fixtures in cells to prevent future inmate suicides. In the years that followed, his recommendation was echoed by another Manitoba judge and federal prison ombudsmen.

When told of the deaths that followed his recommendation, Sandhu went silent for a moment before responding.

“It’s tragic. It’s literally tragic,” he says.

“What good are recommendations if implementation can just be cast aside with impunity?”

ryan.thorpe@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @rk_thorpe

Ryan Thorpe likes the pace of daily news, the feeling of a broadsheet in his hands and the stress of never-ending deadlines hanging over his head.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.