Blood on the prairies While commissioner Donald Smith tried to sway settlers, Louis Riel maintained his grip over Red River. But then came the arrest and execution of Thomas Scott

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 14/02/2020 (2124 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

As Manitoba gets set to mark its 150th anniversary in 2020, the Free Press turns back the clock and takes an in-depth look at the dramatic story of how a small community living on the banks of the Red and Assiniboine rivers stood up to the federal government and demanded a say in the terms of joining Canada. The Red River Resistance of 1869-70 is a story of courage and determination by a group of Manitoba Métis who challenged a colonial mindset in Ottawa and took up arms to protect their democratic, cultural and legal rights.

It begins in October 1869 and culminates in the passage of the Manitoba Act by Parliament in May 1870 — a constitutional amendment that still serves today as the legal framework for Manitoba’s place in Canada. The following is the second instalment of a three-part series that will follow the timeline of what unfolded in the Red River Settlement 150 years ago, and the events that led to Manitoba’s entry into Confederation.

THEY came from far and wide. About 1,000 Red River settlers bundled up on a bone-chilling January afternoon and made their way by foot or sled to the courtyard inside the walls of Upper Fort Garry.

Main players

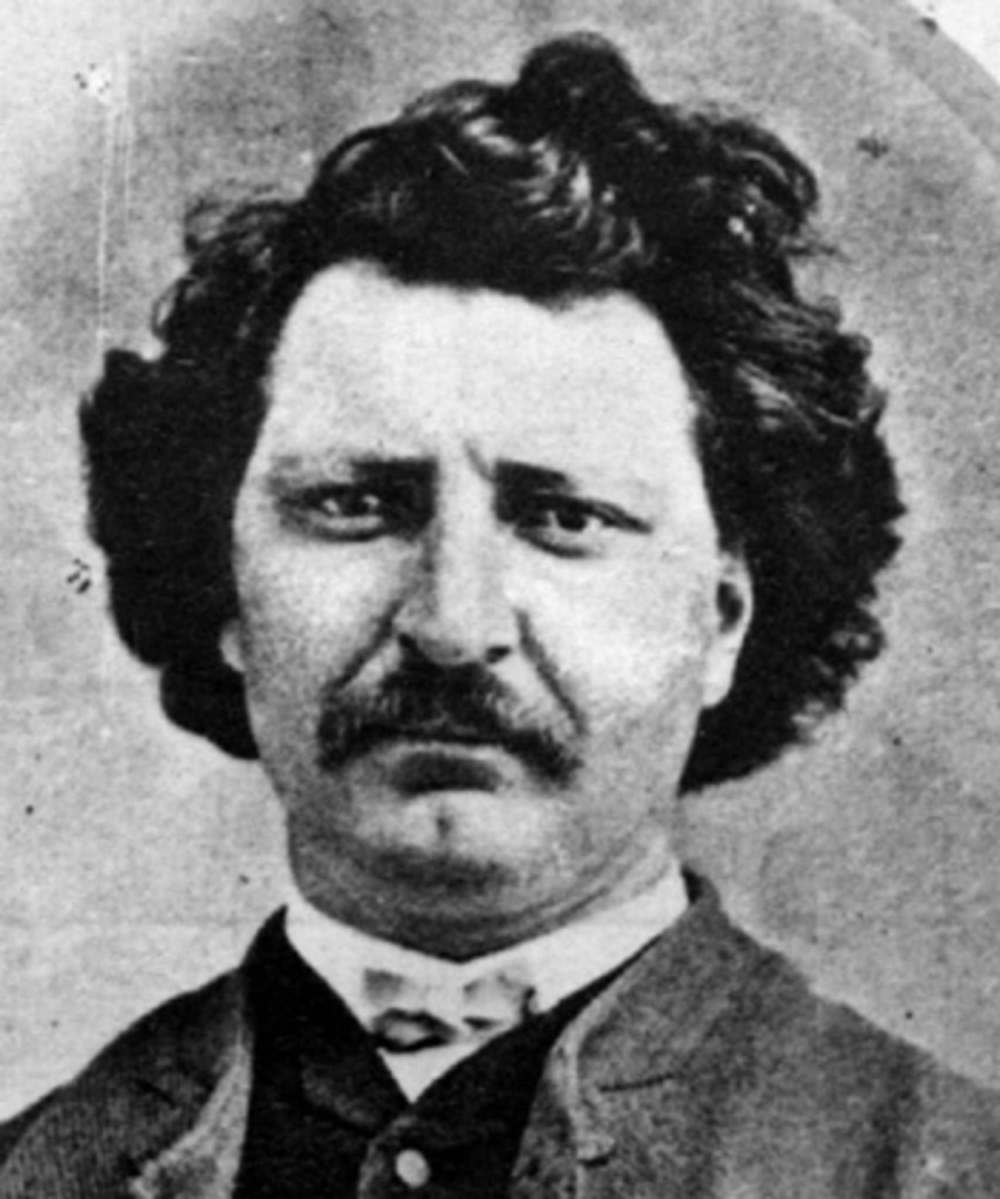

Louis Riel: The leader of the French Métis, Riel prevented the federal government from unilaterally imposing its sovereignty on the Red River Settlement. At age 25, he led the creation of a provisional government and the establishment of an elected “Convention of Forty,” which drafted a bill of rights to take to Ottawa to negotiate Manitoba’s entry into Canada.

Louis Riel: The leader of the French Métis, Riel prevented the federal government from unilaterally imposing its sovereignty on the Red River Settlement. At age 25, he led the creation of a provisional government and the establishment of an elected “Convention of Forty,” which drafted a bill of rights to take to Ottawa to negotiate Manitoba’s entry into Canada.

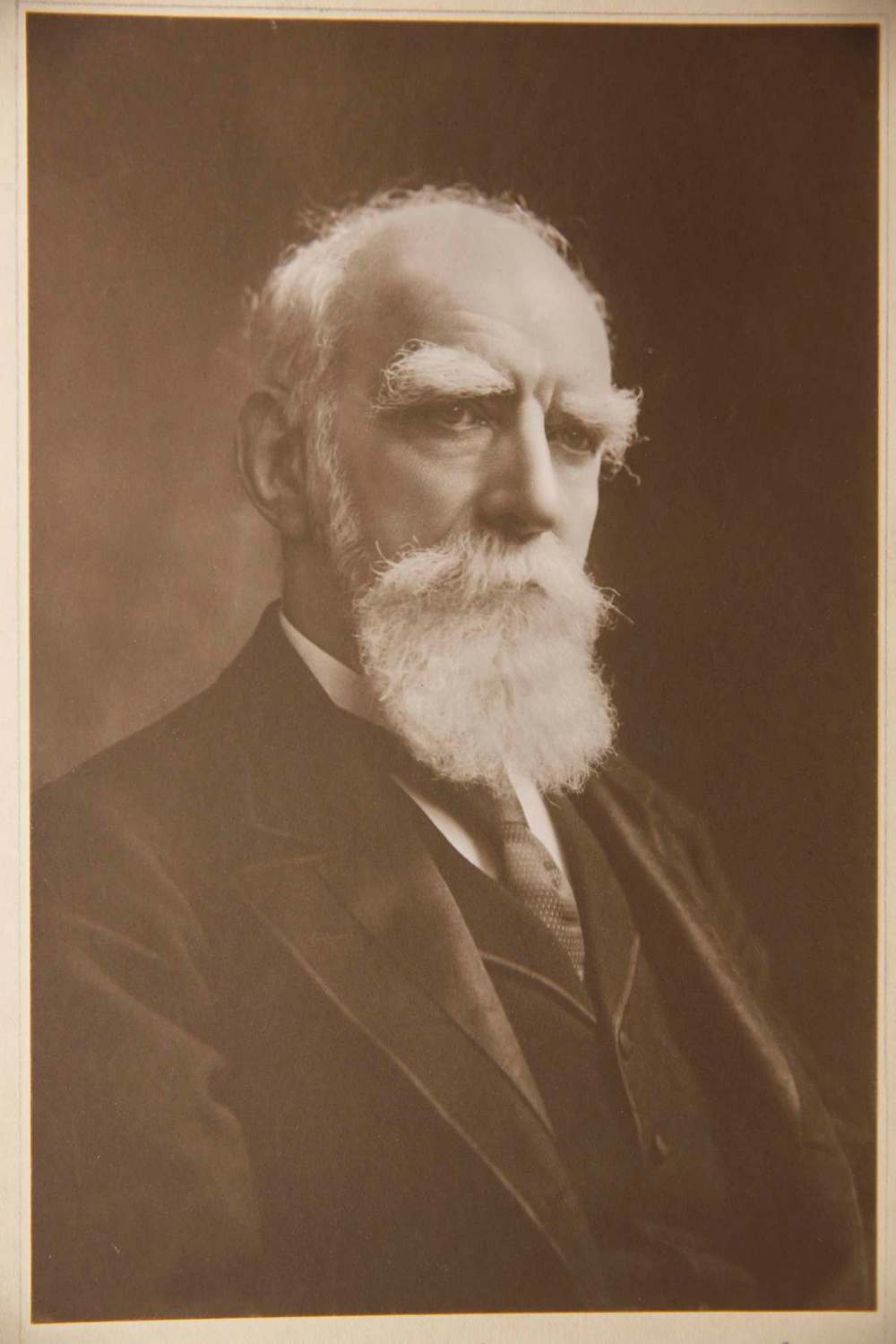

Donald A. Smith: A high-ranking Hudson’s Bay Company official sent to Red River in late December 1869 by prime minister John A. Macdonald to attempt to quell the resistance and sell the idea of Confederation to settlers.

Ambroise Lépine: The adjutant-general in the provisional government and one of the key Métis players in the resistance. Lépine was the only person ever convicted for the execution of Thomas Scott, but was spared a death sentence.

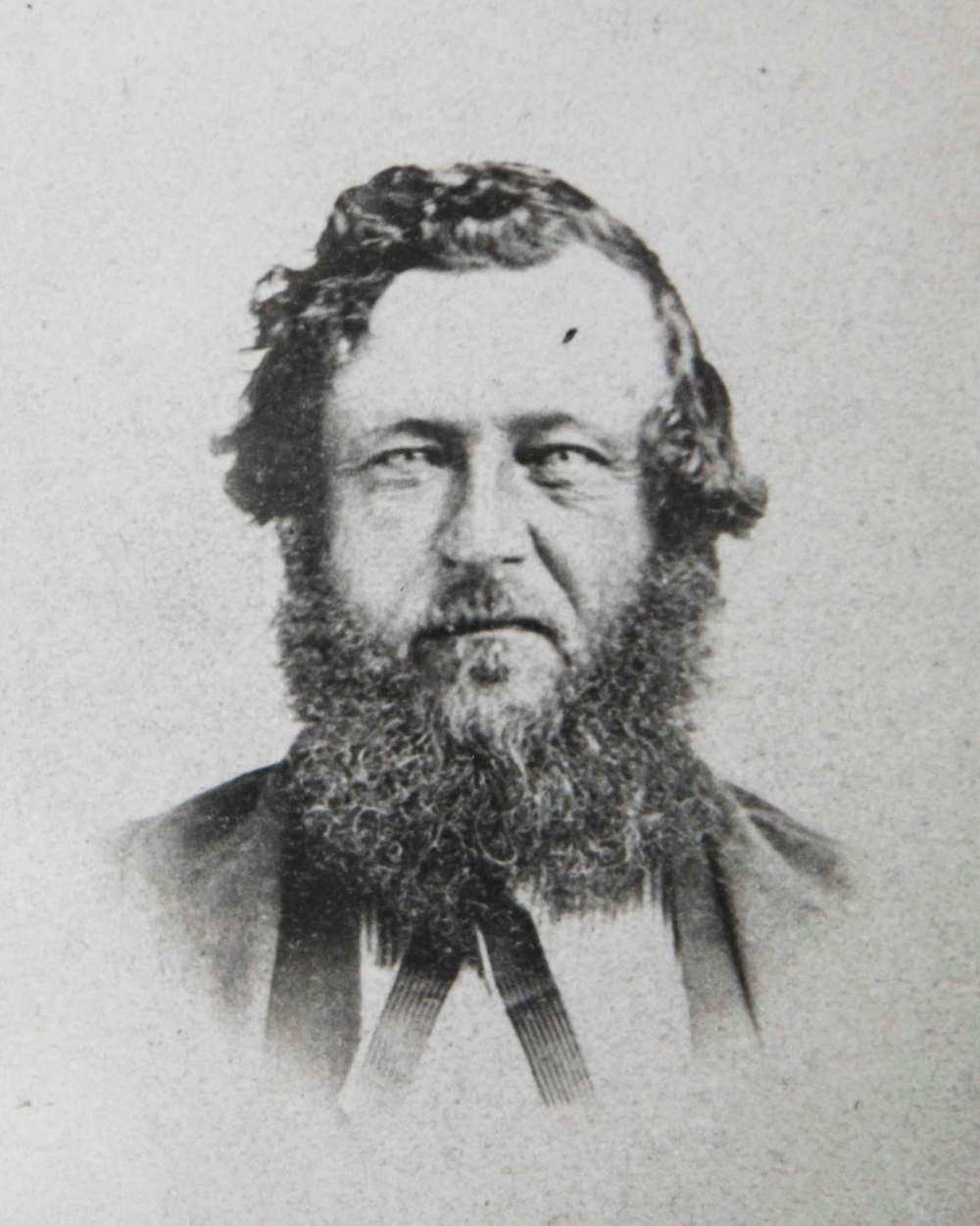

John Christian Schultz: The leader of the self-proclaimed Canadian “loyalists” and chief nemesis of Louis Riel. Schultz was imprisoned at Upper Fort Garry for opposing the provisional government, but later escaped. He would be instrumental in whipping up anti-Métis sentiment in Ontario while delegates from Red River negotiated Manitoba’s terms of entry into Canada.

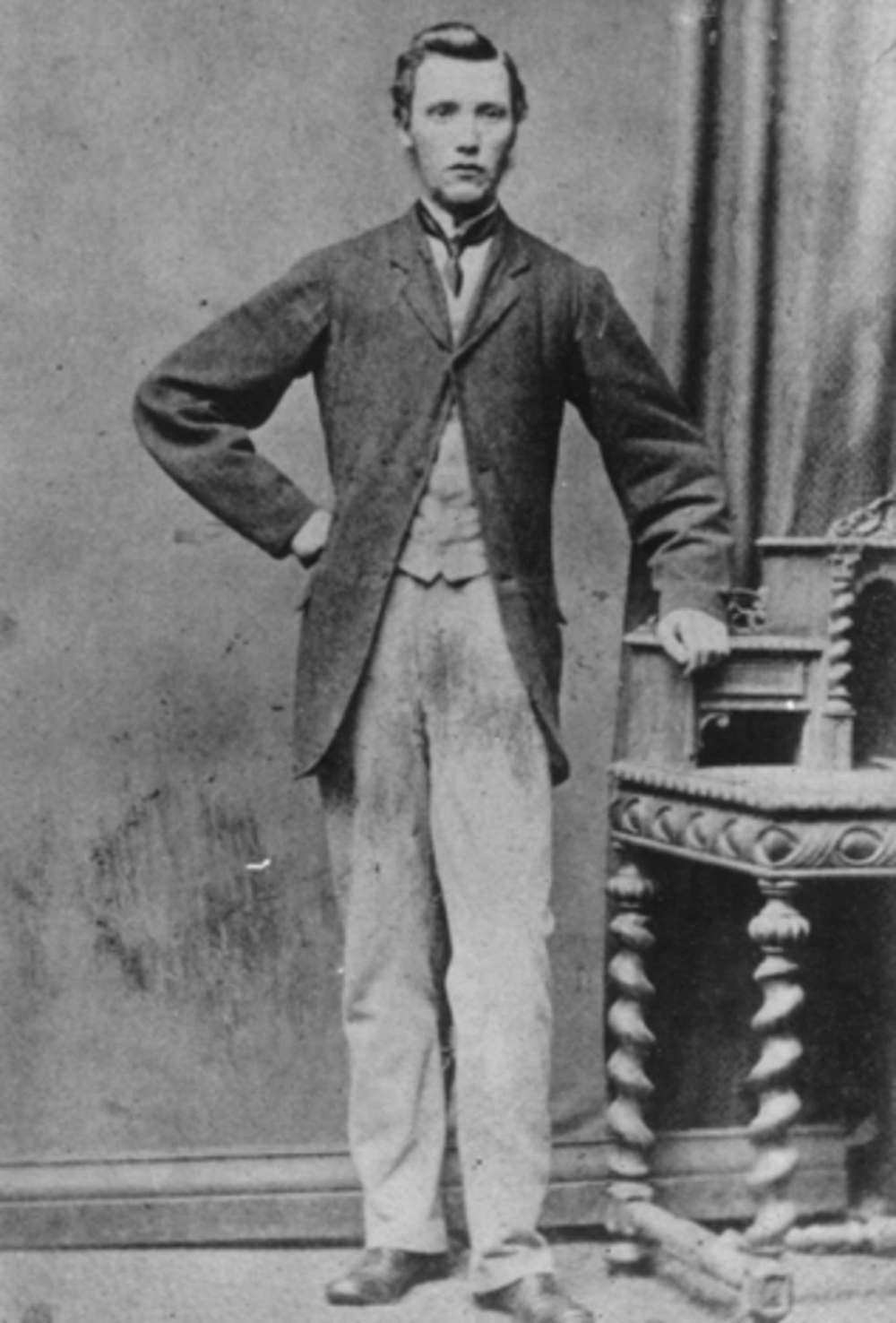

Thomas Scott: An Irish-born labourer, Scott was twice imprisoned by the provisional government and executed by firing squad after he was convicted by a military council of opposing the provisional government and attacking a Métis guard.

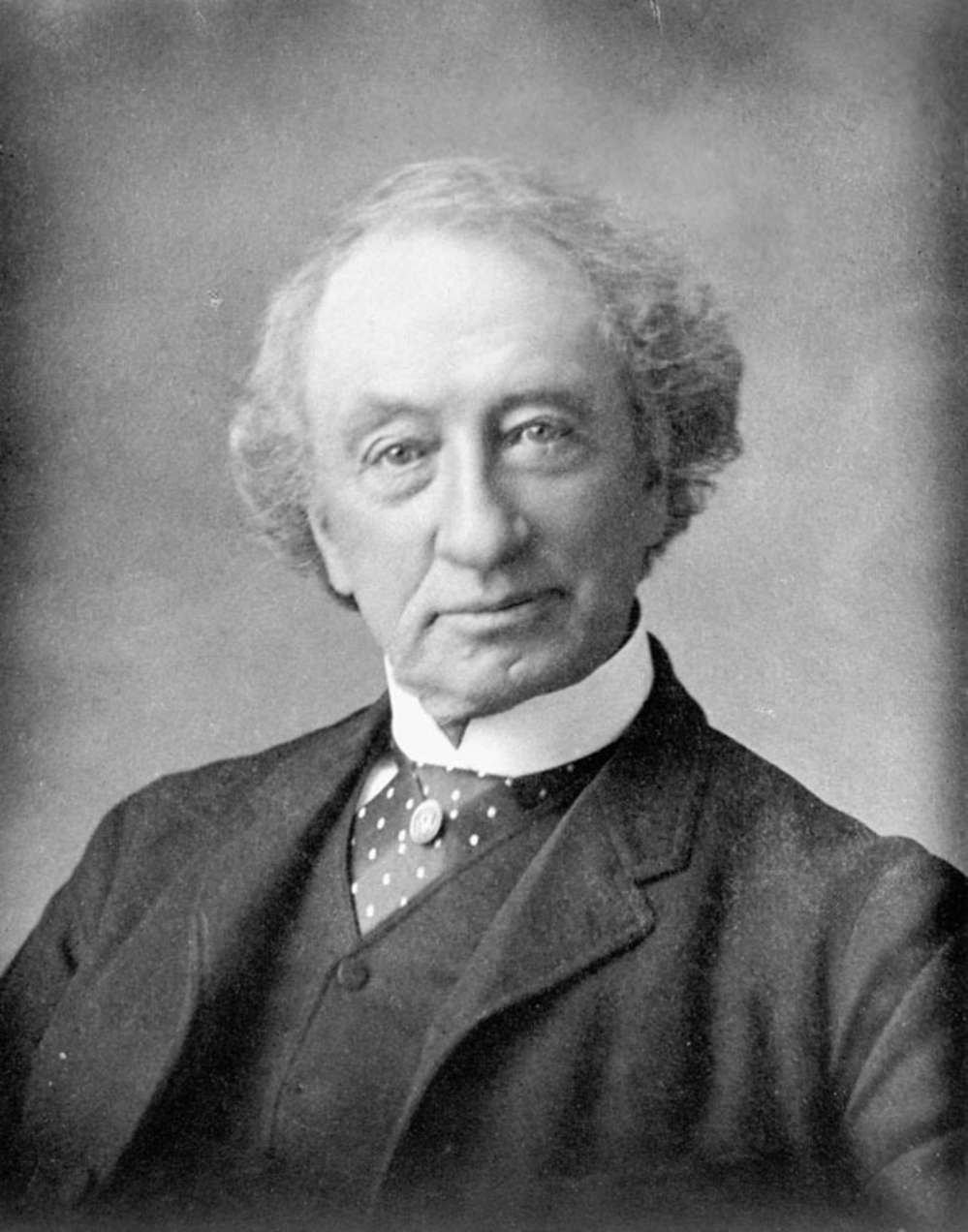

John A. Macdonald: Canada’s prime minister during the Red River Resistance. After a failed attempt to annex the North-West Territories to Canada without consulting the people of Red River, he eventually agreed to negotiate with delegates sent from the settlement.

The man they came to hear was Donald A. Smith, a Hudson’s Bay Company executive sent to Red River by prime minister John A. Macdonald as a special commissioner. His mission: to win over the settlers, defuse the armed insurgency that began two months earlier, and if possible, find a peaceful solution to bringing the settlement into the Canadian fold.

No building was big enough to accommodate the massive crowd (there were only about 12,000 people living in Red River at the time). Instead, most stood for four hours in the open courtyard on Jan. 19, 1870 trying to stay warm in -29 C weather.

Red River born Métis Thomas Bunn chaired the meeting. Judge John Black, head of the local Quarterly Court, was secretary. Louis Riel, leader of the fledgling and still fragile Métis provisional government, served as interpreter for the French-speaking attendees.

It was “the most important meeting ever held in the settlement,” Bunn told the crowd as they opened the proceedings.

Almost three months earlier, armed Métis blocked lieutenant-governor designate William McDougall from entering the Red River Settlement. Riel and his supporters seized Upper Fort Garry in early November, imposed a form of martial law on the community and demanded the federal government negotiate with settlers before annexing the territory to Canada.

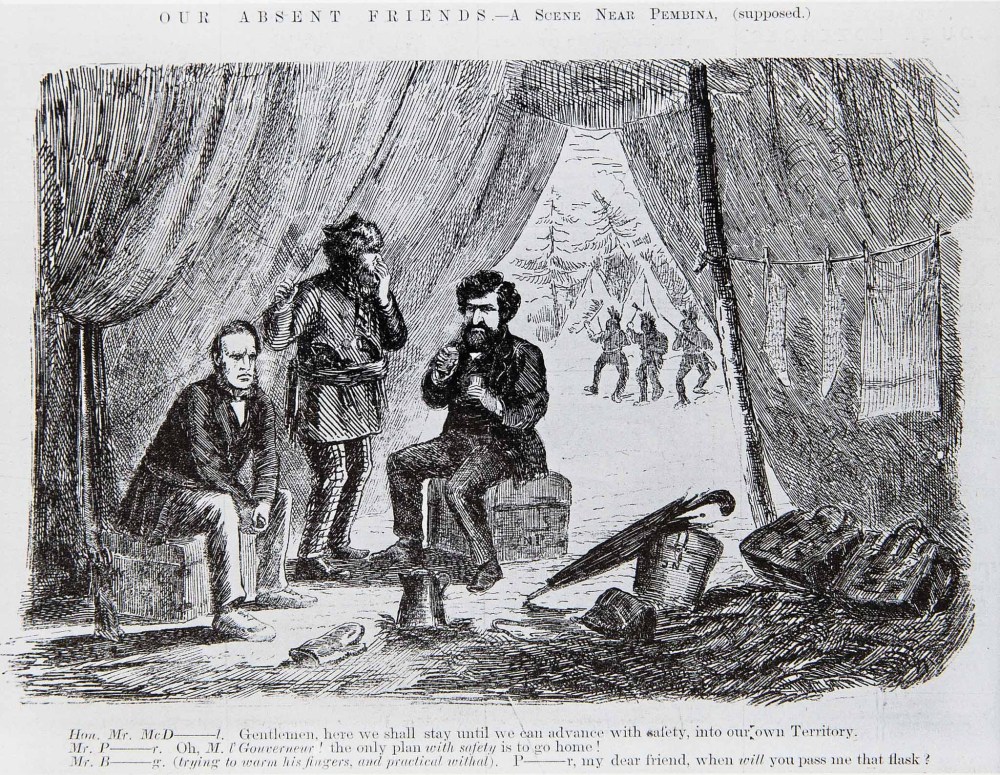

After being holed up for several weeks in Pembina, unable to discharge his duties as the Queen’s representative in the North-West Territories, McDougall left for home before Christmas.

For Macdonald, the insurgency was both a surprise and a thorny political problem he knew he couldn’t solve overnight.

His first attempt to quell the resistance was to send two emissaries to Red River in December — Charles de Salaberry and Jean-Baptiste Thibeault.

Both men failed to have any impact on the community, largely because neither was given the authority (nor the mandate) to negotiate with Red River residents.

Timeline

Dec. 27, 1869 — Donald A. Smith arrives in Red River from Ottawa, sent by prime minister John A. Macdonald to try to quell the resistance and inform the provisional government that Canada is willing to negotiate the terms of entry into Confederation.

Métis leader John Bruce steps down as president of provisional government due to poor health. He is replaced by Louis Riel, who had served as secretary.

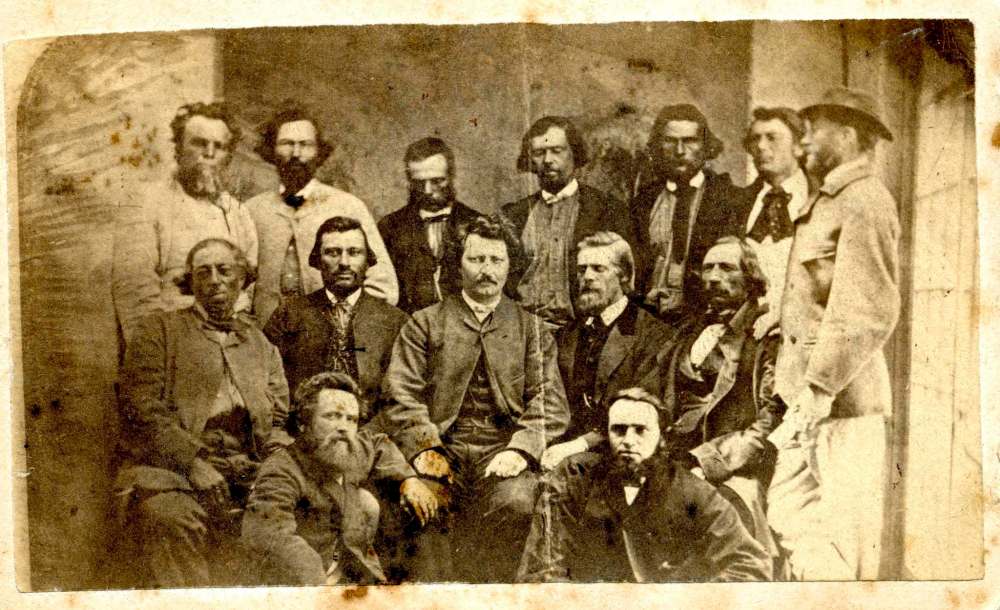

Jan. 19-20, 1870 — Two public meetings are held outdoors at Upper Fort Garry. Donald A. Smith addresses the crowd of about 1,000, the first time a federal representative speaks directly to the people of Red River about joining Canada. Riel makes impassioned speech and moves a motion to create a “Convention of Forty” to consider the future of Red River. The motion passes.

Dec. 27, 1869 — Donald A. Smith arrives in Red River from Ottawa, sent by prime minister John A. Macdonald to try to quell the resistance and inform the provisional government that Canada is willing to negotiate the terms of entry into Confederation.

Métis leader John Bruce steps down as president of provisional government due to poor health. He is replaced by Louis Riel, who had served as secretary.

Jan. 19-20, 1870 — Two public meetings are held outdoors at Upper Fort Garry. Donald A. Smith addresses the crowd of about 1,000, the first time a federal representative speaks directly to the people of Red River about joining Canada. Riel makes impassioned speech and moves a motion to create a “Convention of Forty” to consider the future of Red River. The motion passes.

Jan. 26, 1870 — Convention of Forty, made up of 20 French and 20 English members, meets for first time at the courthouse.

Feb. 3, 1870 — Riel proposes North-West Territories should enter Canada as province, not a territory as proposed by the federal government. Convention of Forty rejects the motion.

Feb. 7, 1870 — Convention of Forty adopts a new “bill of rights” to take to Ottawa to negotiate Red River’s entry into Canada.

Feb. 10, 1870 — Convention agrees to create new provisional government made up of 12 French and 12 English members elected by the people.

Feb. 17, 1870 — A new round of “Canadian loyalist” prisoners are captured by the provisional government outside Upper Fort Garry after a botched plan to attack the fort. Among those captured is Thomas Scott.

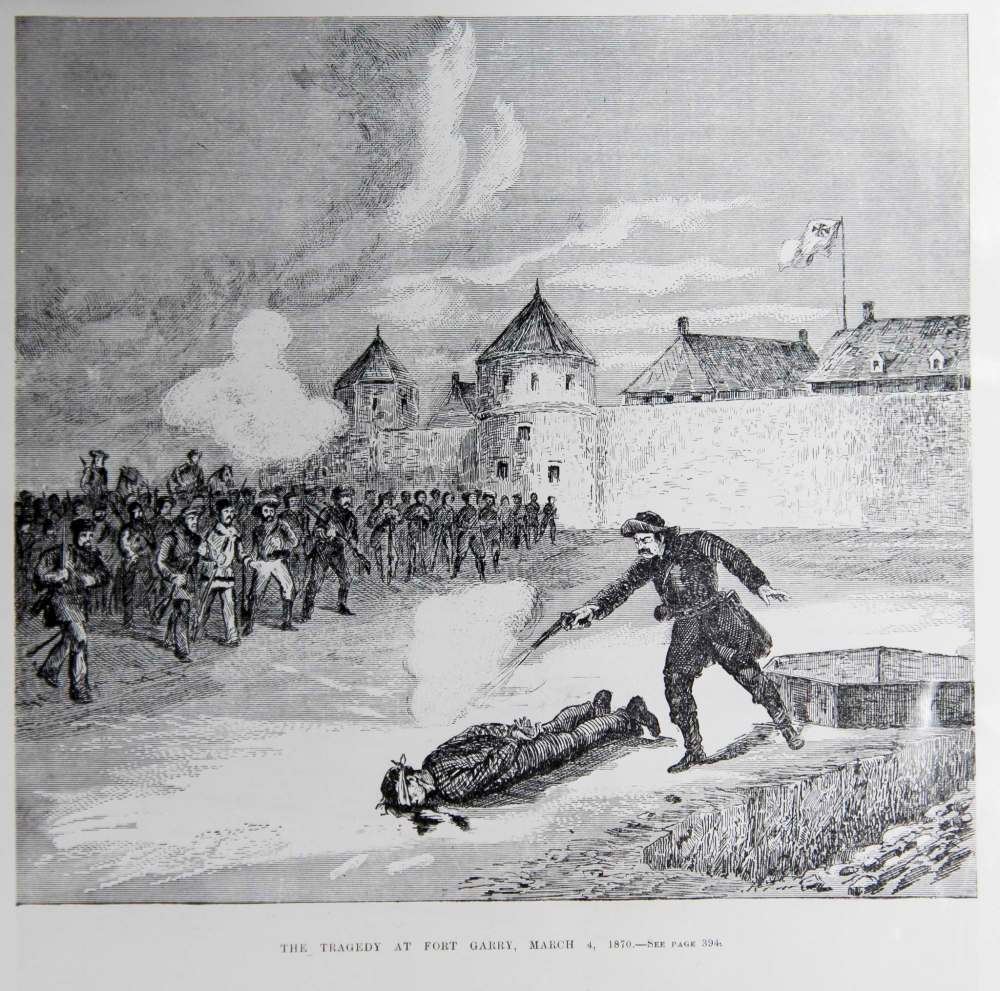

March 3, 1870 — Thomas Scott is tried and convicted by a military council for rebelling against provisional government and for attacking a guard.

March 4, 1870 — Thomas Scott is executed by firing squad outside Upper Fort Garry walls.

Sending troops to Red River was out of the question for Macdonald at that point. The only way for Canadian or British military forces to access the territory in the winter was by train through the U.S. to St. Cloud, Minn., and then by sled to Red River.

It’s doubtful U.S. authorities, still healing from the wounds of a bloody Civil War and themselves semi-interested in annexing the North-West Territories, would have allowed foreign troops to pass through their territory. Besides, no one wanted bloodshed, Macdonald included.

The prime minister’s next move was to send a special commissioner to Red River with a broader mandate and a more convincing sales pitch.

Smith wasn’t authorized to negotiate with the settlers. But his commission did have more teeth than his predecessor’s did.

He made some commitments to the crowd, as they huddled together trying to stay warm: their democratic and property rights would be honoured and Ottawa would be prepared to negotiate further details with representatives of the community.

Canada’s intentions were well-meaning, he told the settlers, urging them to consider what the Dominion had to offer.

Some historians saw Smith’s real mandate as more deceitful. There is some evidence that the special commissioner’s true intention was to undermine Riel’s leadership by using bribes to divide and conquer the settlement. His terms of reference from Ottawa stated the federal government would honour “any pecuniary arrangements that you may make with individuals, in the manner we spoke about.”

No one is sure exactly what that meant. But to some historians, it sounded an awful lot like a green light to offer cash, or promises of employment, to anyone willing to lay down their arms and abandon Riel’s provisional government.

The extent to which Smith bribed people with cash is unclear. But he did succeed by mid-January in weakening the resolve of some Riel supporters, at least temporarily.

The public meeting at the fort was requested by Smith. It was the first time a representative from Canada spoke officially and directly to the people of Red River about joining Confederation.

As cold and uncomfortable as it was standing for the better part of an afternoon outside, those in attendance were interested in what the special commissioner had to say.

Smith had some success on the first day. By most accounts, he was an eloquent and convincing speaker. He piqued the interest of the crowd; so much so that a second meeting was called for the following day.

A crowd of similar size turned up. Indigenous clergy Reverend Henry Cochrane was added to the stage to translate the proceedings into Cree.

It was apparent the federal government was now prepared to take a more conciliatory approach to dealing with the people of Red River.

But talk was cheap. Smith had no authority to conclude a formal agreement.

While he made some headway in convincing the people of Red River that joining Canada would be in their best interest, he didn’t have a mandate to close the deal.

There were still many outstanding issues to address, including how Rupert’s Land would enter Confederation.

Ottawa wanted to annex it as a territory, governed by a federally appointed lieutenant-governor and council. Macdonald promised provincial status with an elected legislative assembly at a later date (after Canadians from the east would flood the area and run for elected office).

Riel was aware of that dynamic, which is why he aggresively pursued provincial status.

Riel convinced the assembly that before the settlement could agree to join Canada, the terms of entry would have to be negotiated. The Métis leader, himself an effective orator, closed with an impassioned speech, portions of which were published the next day in the local Métis-controlled New Nation newspaper:

“I came here with fears — we are not yet enemies,” Riel told the crowd, drawing loud cheers. “But we came very near being so. As soon as we understood each other, we joined in demanding what our English fellow subjects in common with us believe to be our just rights.

“I am not afraid to say our rights; for we all have rights. We claim no half rights, mind you, but all the rights we are entitled to. Those rights will be set forth by our representatives, and, what is more, gentlemen, we will get them.”

“I am not afraid to say our rights; for we all have rights. We claim no half rights, mind you, but all the rights we are entitled to. Those rights will be set forth by our representatives, and, what is more, gentlemen, we will get them.”–Louis Riel

It was a defining moment for Riel, who had struggled in the days leading up to the public meeting to maintain support from his core constituents.

Just prior to his speech, the Métis leader moved a motion to create a convention of 40 delegates — 20 French and 20 English — to consider Smith’s commission and decide the appropriate direction for the settlement.

The motion passed. A “Convention of Forty” was soon created and Riel enjoyed renewed support. Whatever influence Donald Smith had when he arrived at Red River began to fade.

Riel had “put himself once more at the head of events in Red River,” Manitoba historian William Morton wrote in his introduction to Alexander Begg’s Red River Journal.

Arbitrary imprisonment occurred on a regular basis in Red River in the fall and winter of 1869-70.

There was no due process, no judicial principles that guaranteed an individual’s presumption of innocence before guilt was proven in a court of law. There were no bail hearings, or anything resembling bail court. Even the Quarterly Court that existed in Red River prior to the resistance was suspended for about two months during the height of the armed conflict.

For the most part, Riel and the Métis were the police, judge and jury when it came to arresting and jailing their enemies — or perceived enemies — at Upper Fort Garry. They did so frequently.

Even a hint of insubordination or a perceived threat against the provisional government would be grounds for detention.

It wasn’t unusual to have 30, 40 or 50 political prisoners locked up at any given time. Those captured were often released with a promise not to disturb the peace (the closest thing to bail), or a pledge not to challenge the authority of the provisional government.

John Christian Schultz was one of those political prisoners. Schultz, who came to Red River from Ontario in 1861 in anticipation of annexation, led a group of Canadian “loyalists” opposed to Riel’s regime.

He was a polarizing figure in the settlement. His acrimonious relationship with the Métis — and with Riel in particular — was symbolic of the struggle between the imperial forces in Ottawa and local interests.

Schultz’s “Canadian party,” as he called it, supported joining Canada unconditionally. Many from the east who had already arrived in Red River hoped to profit from land acquisitions that would grow in value once Rupert’s Land joined Confederation.

Schultz and his supporters had been politically active in the settlement for several years, not only promoting Canadian annexation but also excoriating the Hudson’s Bay Company and its political monopoly over the region. They used the only newspaper in Red River at the time, the Nor’ Wester (eventually shut down by Riel), to advance their political agenda.

Schultz and his supporters not only opposed the Métis and their provisional government, they were openly contemptuous towards them.

Racial and religious tensions were ever present, which shaped the inner-conflicts in the the settlement.

The transplanted Ontarians were focused on removing whatever barriers that stood in the way of Canadian annexation, even if that meant trampling on the rights of local settlers. For that, they found themselves behind bars on a regular basis in whatever makeshift cells the Métis arranged for them at Upper Fort Garry.

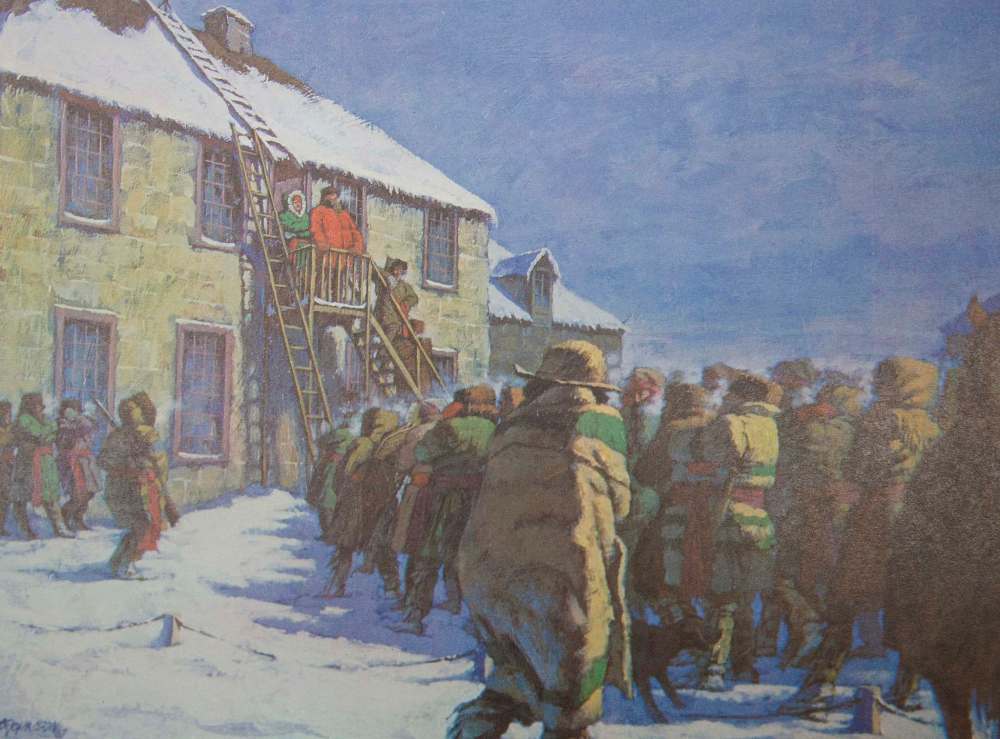

One of the most significant mass-arrests occurred in December after an armed standoff between the Métis and a group of about 40 Schultz supporters, who had barricaded themselves in Schultz’s home in the village of Winnipeg. The Métis suspected Schultz’s group was planning an attack on the fort.

It could have been a bloodbath, which would have marked the first casualties of the resistance.

Fortunately for all involved, cooler heads prevailed.

Schultz and his supporters surrendered, no blood was shed, and they were all taken prisoner, including Thomas Scott, whose execution three months later would be the most pivotal part of the resistance.

Schultz, Scott and others escaped from captivity a few weeks later in January.

It’s believed Schultz used a penknife smuggled in by his wife to dig his way through a window frame at the fort. He removed it, escaped from the building where he was housed and scaled one of the walls, injuring himself in the process.

Schultz remained in hiding for weeks, avoiding re-arrest — Riel ordered him shot on site if found — until he eventually fled to Ontario to stir up anti-Riel sentiment among eastern Canadians.

It didn’t take long for the new Convention of Forty to elect members and begin drafting a fresh list of rights to take to Ottawa. It was agreed a delegation of three would be sent east to negotiate the terms of entry into Confederation.

But first, those terms had to be agreed upon by the convention. There was still much work to do.

Riel faced another hurdle: he found himself in a minority situation within the Convention of Forty. He only had 17 of 40 members on his side.

Three of the francophone Métis elected to the convention, including Charles Nolin, one of Riel’s chief political adversaries, were part of a small group of Riel opponents. The other 20 were from the anglophone side. That meant Riel could be overruled on some of his proposals, which he was more than once.

The convention opened in conciliatory fashion. Several articles were drafted and agreed upon with little fuss.

But Riel’s motion for the territory to enter Confederation with provincial status was defeated. So was his demand that the sale of Rupert’s Land by HBC to Canada be nullified and renegotiated with the involvement of representatives from Red River.

Tensions ran high and a furious Riel accused the three French members who voted against him of being traitors.

“Riel said the convention had beaten him this time, but he would beat them yet,” local merchant Alexander Begg — who kept a detailed diary of the resistance — wrote in his journal Feb. 5, 1870.

Riel was still very much in charge of the settlement at the time. He continued to hold prisoners at the fort, even while the convention deliberated.

While there were some democratic principles behind the formation of the committees, provisional governments and conventions in 1869-70 Red River, Riel ultimately called the shots.

When push came to shove, he ruled with an iron fist, sometimes with threats of violence and death. He commanded hundreds of armed and skilled Métis buffalo hunters loyal to his cause.

No group or faction in the settlement could match that. Those who tried, failed, and usually found themselves behind bars.

Still, Riel’s preference was to seek unity among the French, English and others in the settlement, which he ultimately succeeded in doing. But his message was clear: if others didn’t want to join the French Métis in demanding the rights of Red River settlers, Riel and his supporters would go it alone.

If anyone got in their way, blood would be spilled.

“In the town of Winnipeg brilliant fireworks were set off and bonfires lighted — guns fired and cheering and drinking universal. A regular drunk commenced in which everyone seemed to enjoy.”–Journal of Alexander Begg

A bill of rights was eventually agreed to by the convention. It differed somewhat from the list of rights the Métis had published in December.

But it had similar elements to it: the protection of property rights; bilingualism in the courts and the legislative assembly; the right to an elected council; demands for a railroad to connect Red River to the east; and several clauses about taxation and how land would be organized. It included a demand that treaties be negotiated with First Nations.

There were a number of versions of these lists that emerged during 1869-70. This would not be the final one delegates would take to Ottawa. But it was an advanced copy.

In the meantime, the issue of who would govern Red River still had to be dealt with until negotiations with the federal government were settled. It was agreed on Feb. 10 by the convention that a renewed and elected provisional government made up of 12 French and 12 English members would be formed, with several officers and a president (Riel) appointed by the Convention of Forty. A two-thirds vote of the assembly would overrule the veto of the president.

Despite the setbacks and the underlying tensions that remained in the settlement, the people of Red River were beginning to move in unison towards a negotiated settlement with Canada.

They were also doing so through democratically elected institutions, which didn’t exist in Red River prior to the resistance (at least not since colonial rule). Red River was governed by the Hudson’s Bay Company and an appointed Council of Assiniboia prior to the insurgency.

The announcement of the new provisional government was greeted with celebration in the community. There was, for the first time in many weeks in Red River, a sense of good things to come.

“In the town of Winnipeg brilliant fireworks were set off and bonfires lighted — guns fired and cheering and drinking universal,” Alexander Begg wrote in his journal. “A regular drunk commenced in which everyone seemed to enjoy.”

Riel, who wasn’t much of a drinker, marked the occasion in his own quiet way.

No sooner had circumstances quieted down in Red River when a renewed threat emerged.

Just when it appeared the future was looking bright for the would-be Manitobans, armed conflict would once again threaten the relative peace of the community.

It would lead to events that would forever change the life of Louis Riel.

Unaware of (or perhaps disinterested in) the constitutional developments of the past few days at Upper Fort Garry, John Christian Schultz and his supporters were planning an attack on the fort.

They sought the immediate release of all prisoners and planned to install a provisional government of their own. But their efforts were clumsy, poorly planned and marred by weak leadership.

The Canadian “loyalists” would make the trek from Portage la Prairie, through Headingley and onto the parish of Kildonan, amassing an armed regiment of a few hundred men who would take the fort.

At least that was the plan. But they had no idea how to carry it out.

In the end, they were so poorly armed and disorganized, the mission was abandoned.

Schultz, still a wanted man by Riel, fled. Most of the others either dropped out along the way, or simply went home. But a group of about 40 detractors decided to walk within eyesight of Upper Fort Garry on their way back to Portage.

Riel and the Métis got wind of the failed coup. When they spotted the small group near the fort, they deployed a squad of armed horsemen and took them prisoner.

Among the captured was Thomas Scott (his second imprisonment after escaping in January).

His martyrdom in Ontario following his execution two weeks later would send ripples through the Red River Valley.

Nobody knew it at the time, but the arrests of mid-February 1870 and the subsequent death of Scott would forever change the face of the Red River Resistance.

tom.brodbeck@freepress.mb.ca

Tom has been covering Manitoba politics since the early 1990s and joined the Winnipeg Free Press news team in 2019.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.