Old anger, new province

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 15/05/2020 (2125 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

John A. Macdonald was making plans to send a military force to Red River long before the Manitoba Act was approved by Parliament.

The prime minister didn’t make it public at the time, but preliminary discussions to send troops to the Northwest to establish Canadian sovereignty began as early as December 1869.

Officially, it would be a mission of peace to help manage the settlement and “cause law and order to be respected,” Macdonald told the House of Commons, the same day he unveiled details of the proposed Manitoba Act. He assured the house the expedition would be deployed “in no hostile spirit.”

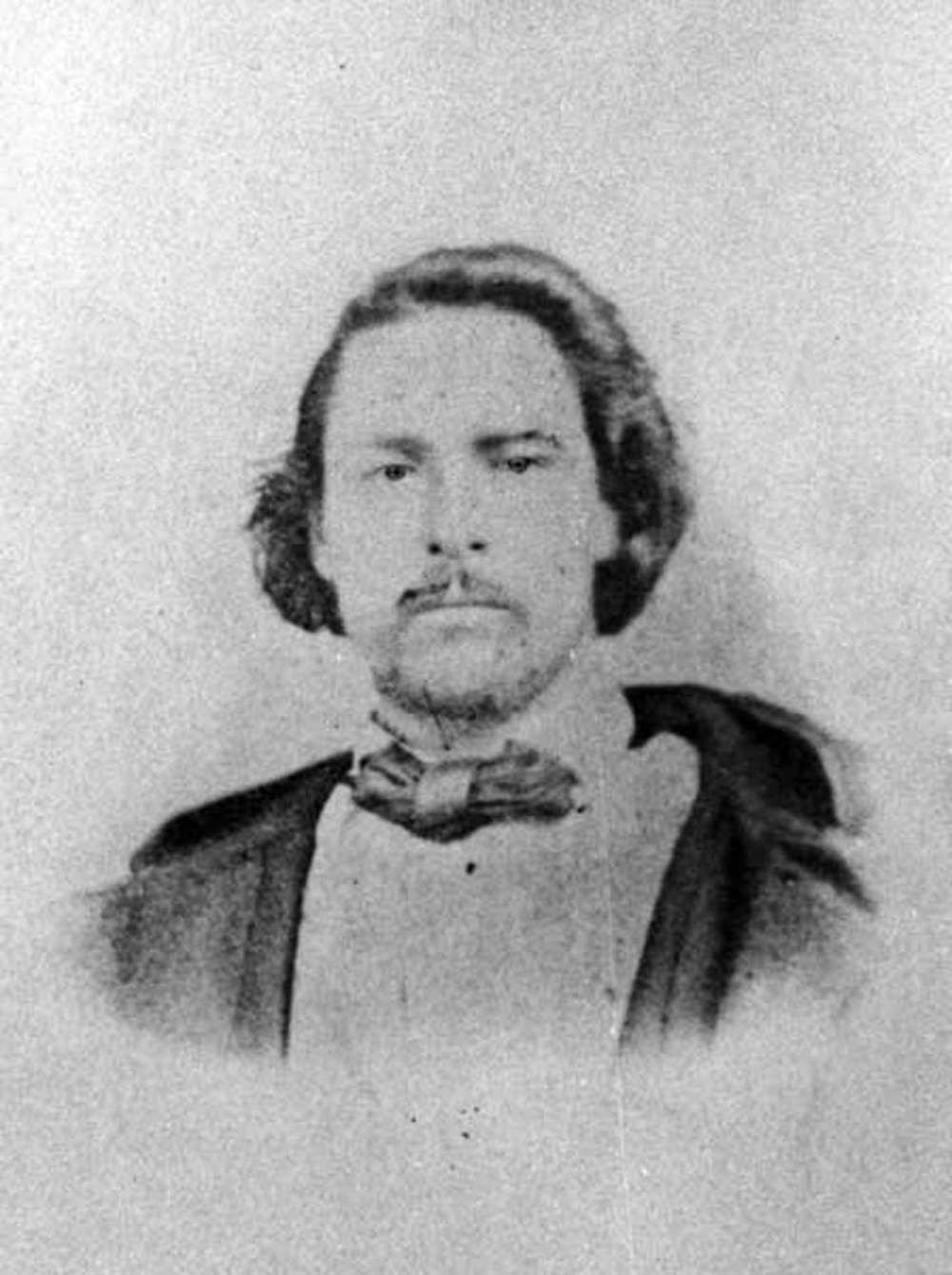

In reality, the military operation was a well-armed, battle-ready force made up of British soldiers and volunteer Canadian militia, many of whom had vengeance on their minds and a thirst to topple the “rebellion” at Red River. It was the beginning of what would be Métis leader Louis Riel’s lifelong exile from Canada.

“The whole tone and temper of the expedition, indeed, from the commanding officer down was hostile to the Métis and punitive in intent,” wrote Manitoba historian William Morton.

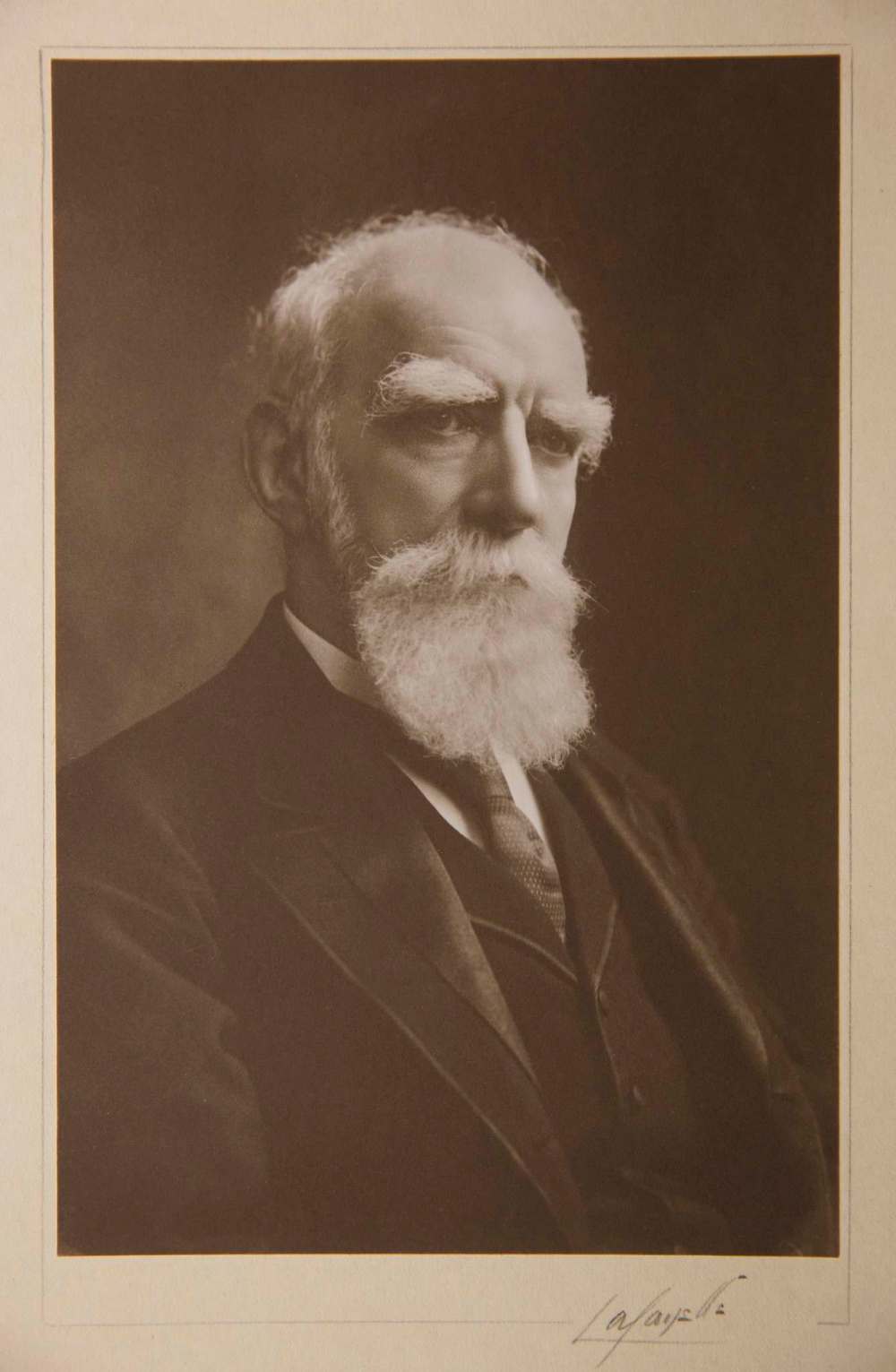

Col. Garnet Wolseley, a career British soldier experienced in combat operations around the world, was chosen as field commander. He headed the 60th Rifles, a force of 373 officers and men that represented the core of the expedition. This would be the British military’s final operation in North America. Wolseley also had command of two militia battalions, one from Ontario and one from Quebec (though most of the Quebec contingent were Ontarians). Many who signed up were eager to avenge the death of Thomas Scott. In total, the expedition numbered more than 1,200.

Most who travelled between Eastern Canada and Red River in those days would do so by train through the United States. But there was no way American authorities would allow British and Canadian troops to pass through their territory. That left the expedition with no choice but to use the old voyageur route through the Great Lakes and overland.

The ink was barely dry on the recently passed Manitoba Act when Wolseley left Collingwood, Ont., on May 21, 1870, with the first detachment of 51 men. They travelled by steamship through Lake Huron and Lake Superior. The soldiers carried Snider breech-loading rifles with 60 rounds of ammunition. Some also brought their own revolvers. The remaining detachments followed in subsequent days. All battalions reached Thunder Bay by June 13.

It was an arduous, three-month journey through rough terrain, often in gruelling, mosquito-infested conditions. The men endured long portages and braved rough rapids.

Wolseley arrived at Fort Frances July 31. By then, word had arrived in Red River that the military expedition was nearing. Despite a proclamation of peace sent by Wolseley to the settlement (which Riel published and distributed in the community), there were fears the intentions of this campaign were anything but peaceful. Those concerns were well-founded. Wolseley himself confirmed it in subsequent writings.

“Personally, I was glad that Riel did not come out and surrender, as he at one time said he would, for I could not then have hanged him as I might have done had I taken him prisoner when in arms against his sovereign,” Wolseley would later write.

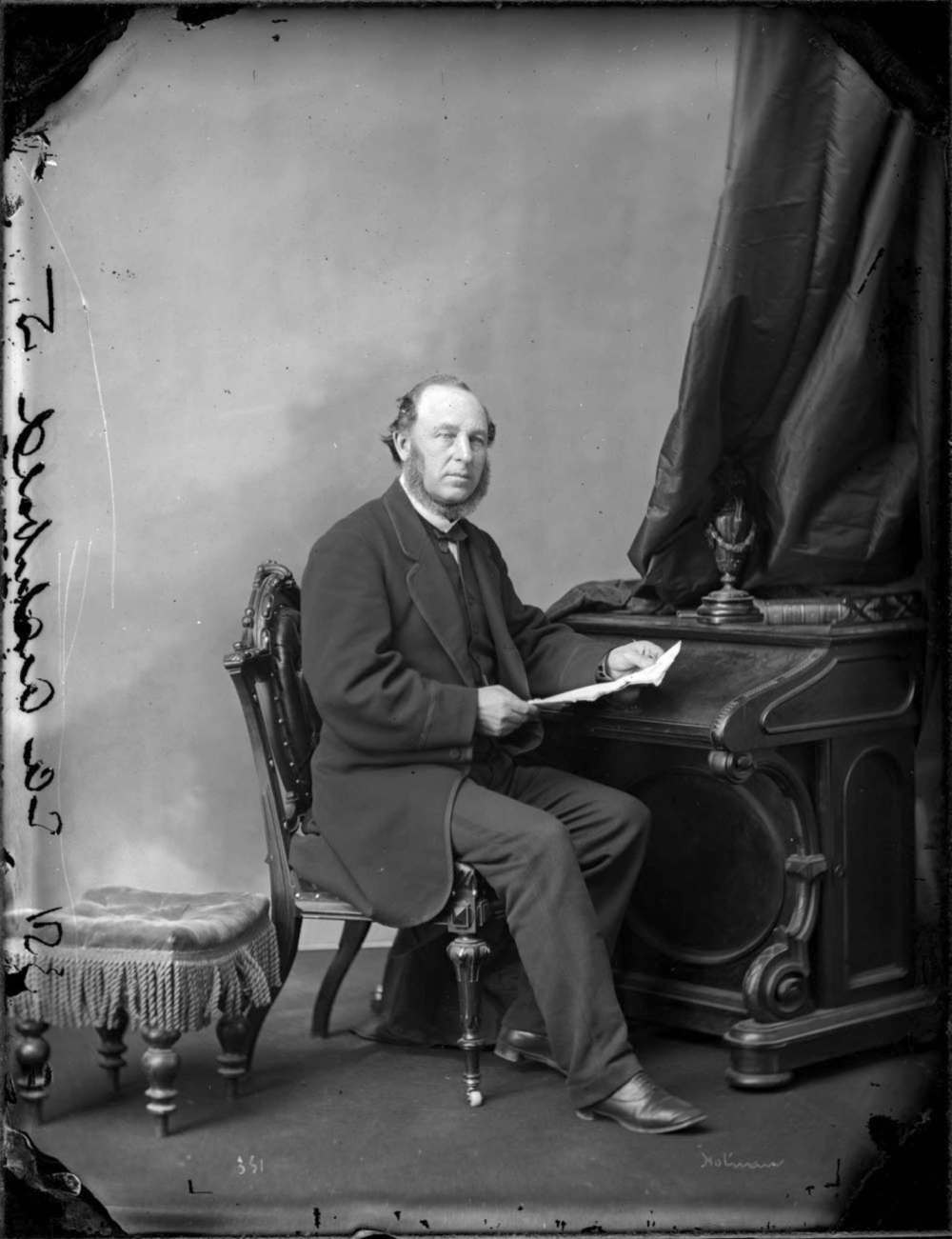

The expedition made its way along the Winnipeg River and arrived at Fort Alexander Aug. 20. The militia was close behind. There, Wolseley was met by Donald A. Smith, the special commissioner sent to Red River by Ottawa over the winter in an attempt to thwart the resistance. Smith speculated to Wolseley that Riel may be mounting an armed resistance; a false claim that put the colonel and his troops on even higher alert.

By the summer of 1870, Riel no longer had the military force he commanded over the winter months. He couldn’t have mounted much of a resistance even if he wanted to. Besides, once the Manitoba Act was approved by Parliament in May, the provisional government was under the impression there would be a peaceful transition of power. Nobody in Red River was spoiling for a fight. Many were looking forward to the end of what had been a long and disruptive period in their lives.

The main barrier to a peaceful transition was the late arrival of lieutenant-governor designate Adams Archibald. The newly appointed Queen’s representative didn’t reach Red River until days after Wolseley arrived (for reasons that were never made clear). Archibald could have travelled through the U.S. by train and arrived in Red River long before the troops. Had he done so, a peaceful transfer of authority could have occurred without the need for military intervention. Instead, the transition occurred at the end of a bayonet.

Wolseley and eight brigades of regulars in 50 boats camped at Elk Island Aug. 21 (just north of Victoria Beach). The next day, they made their way to the mouth of the Red River and rowed upstream to Lower Fort Garry, north of Winnipeg. They were greeted with cheers, waving handkerchiefs and ringing church bells from the banks of the Red, mostly from local anglophone settlers. Following a planned meal at the “stone fort” organized by Smith, they stayed the night under heavy rainfall.

It was obvious by then to Riel and his supporters there would be no symbolic transfer of authority. Bishop Alexandre-Antonin Taché of St. Boniface (who had been away in Rome for most of the Red River Resistance) told Riel he was assured by the federal government that Archibald would arrive before the troops. Taché had travelled to Ottawa a month earlier to try to secure an amnesty for Riel and others. As of late August, the Queen’s representative was nowhere to be found.

On the morning of Aug. 24, Riel got word the troops were just a few miles down river. The Métis leader, realizing he had been misled, bolted from the south gate of Upper Fort Garry mid-breakfast. He crossed the river to St. Boniface and cut the ferry cable behind him. After alerting Taché to witness the arrival of the British military with his own eyes, Riel watched from across the river as the troops docked their boats and headed to the empty fort. They entered through the south doors, which had been left open by Riel. Finding no one inside, they ransacked parts of it, looking for whatever documentation and evidence they could find.

Riel, knowing his safety was in jeopardy, headed south.

Wolseley would later write that it was “a sad disappointment to the soldiers,” there was no rebellion to put down, providing further evidence of the expedition’s true intentions. Archibald wouldn’t arrive for another nine days. In the meantime, Wolseley put Smith in charge of Upper Fort Garry until Archibald’s arrival. The British troops left Red River Aug. 29, leaving behind the Canadian militia to ostensibly maintain order. They did the opposite.

Many of them got the revenge they were looking for. There were brawls in saloons between Canadian soldiers and Métis residents and reports of physical and verbal abuse against local settlers. Elzéar Goulet, one of Riel’s supporters and a member of the military tribunal that sentenced Thomas Scott to death, was murdered. He was chased down to the Red River by a mob that included Canadian soldiers and drowned after being struck in the head with a stone. No one was ever held responsible for his death.

It was a messy and tragic end to the Red River Resistance. Like the resistance itself, it was also entirely avoidable.

Tom Brodbeck is an award-winning author and columnist with over 30 years experience in print media. He joined the Free Press in 2019. Born and raised in Montreal, Tom graduated from the University of Manitoba in 1993 with a Bachelor of Arts degree in economics and commerce. Read more about Tom.

Tom provides commentary and analysis on political and related issues at the municipal, provincial and federal level. His columns are built on research and coverage of local events. The Free Press’s editing team reviews Tom’s columns before they are posted online or published in print – part of the Free Press’s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

![Thomas Scott (c. 1842 – 1870) was an Irish-born Canadian and fervent Orangeman. Scott was born in the Clandeboye area of County Down, in what is now Northern Ireland.[1] He was recruited by Canada to fight in the Red River Rebellion and was captured and imprisoned in Upper Fort Garry by Louis Riel and his men while trying to attack it along with 34 other volunteers. Scott made an attempt to escape but was recaptured by Riel's men and was summarily executed for committing insubordination. Scott's execution led to an outrage in Ontario, and was largely responsible for prompting the Wolseley Expedition, which forced Louis Riel, now branded a murderer, to flee the settlement. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Scott_%28Orangeman%29](https://dev.winnipegfreepress.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2022/05/Thomas+Scott.jpg?w=100)