New province, old hatred Colonialism and racism have been a part of Manitoba's history almost from the instant it became part of Canada

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 10/07/2020 (2070 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

If Red River residents had any doubts that taking up arms to block a federally appointed lieutenant-governor from entering their settlement in the fall of 1869 was the right decision, a speech given by the disgruntled nominee eight months later probably put it to rest.

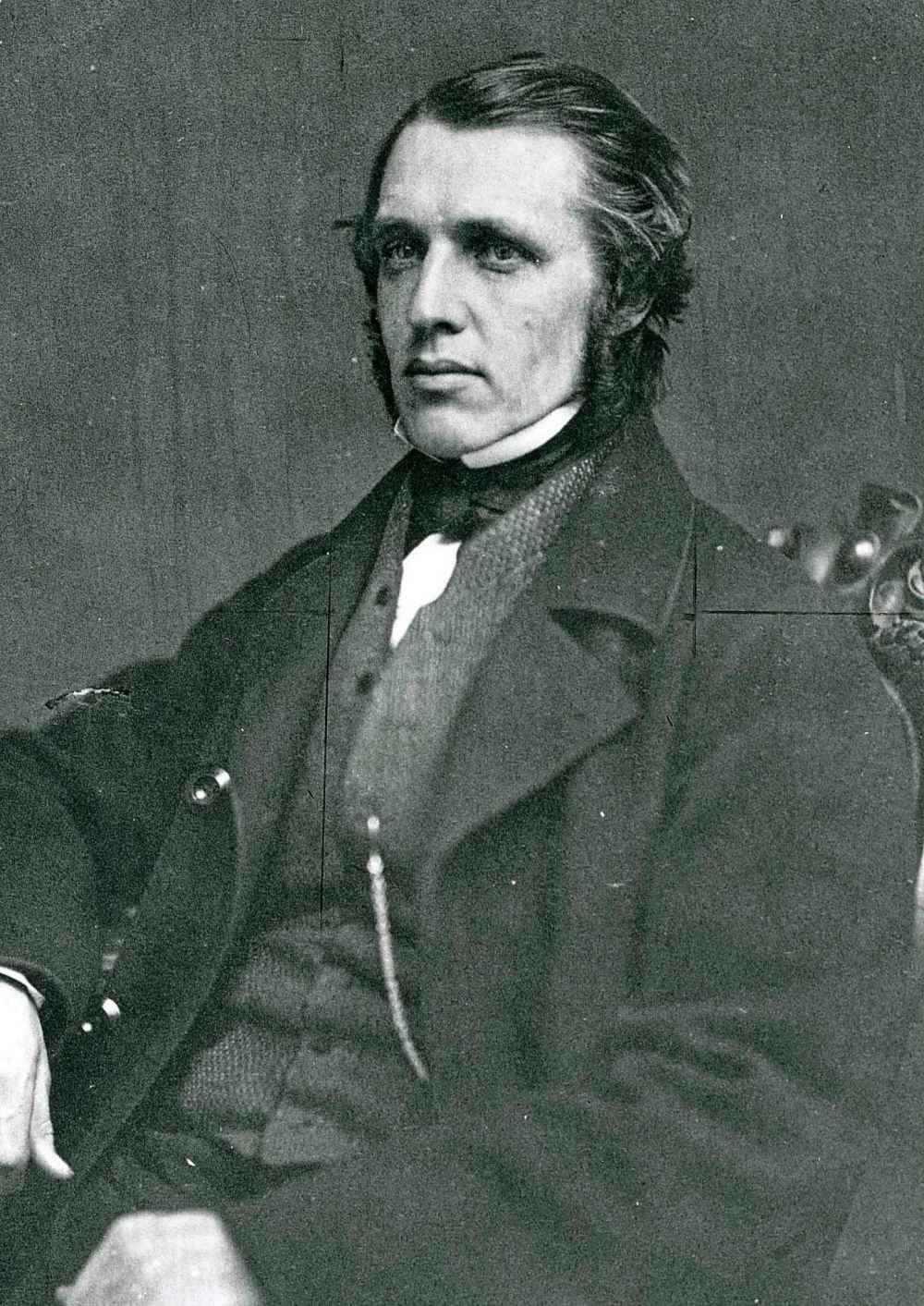

William McDougall, the MP for North Lanark, Ont. who was appointed lieutenant-governor in 1869, was stopped by armed Métis horsemen at the U.S. border in November of that year, during the early days of the Red River Resistance. McDougall, who ended up returning to Ottawa and never took his seat as the Queen’s representative, complained in a vile, bigoted speech to his constituents less than a year later that all the valuable land in Manitoba had been taken up by the Métis.

“The only land, indeed, that any intelligent Canadian would seek, in the early settlement of the country to purchase or to cultivate, is ‘reserved,’ locked up in the hands of lazy and ignorant half-breeds, without any claim whatever to this larger part of it, and for no purpose that anyone can see but to keep out white men, or to put money into the pockets of the priests,” McDougall said. “This reserved tract contains the water and timber, and the river system, which constitutes the highway of the emigrant and trader. It contains all that is at present of any value to the province.”

An excerpt of McDougall’s speech was published in Manitoba’s only newspaper at the time, The New Nation. The paper’s editor said it ran the excerpts to prove that allowing McDougall into the community, as some had suggested at the time, would have been a grave error.

“His delicate reference to our ‘lazy, ignorant half-breeds,’ is very flattering to our industrious and enterprising native farmers, the results of whose long labour and toil may now be seen on the banks of the Red River and Assiniboine, where some farms may be found to equal, if not exceed, in extent of cultivation and general prosperity, anything that Mr. McDougall can show among his favourites of North Lanark,” the newspaper wrote.

“His delicate reference to our ‘lazy, ignorant half-breeds,’ is very flattering to our industrious and enterprising native farmers, the results of whose long labour and toil may now be seen on the banks of the Red River and Assiniboine, where some farms may be found to equal, if not exceed, in extent of cultivation and general prosperity, anything that Mr. McDougall can show among his favourites of North Lanark.” – The New Nation

Surely the most deserving people to occupy the “good” land are those who were born and raised in Red River, the newspaper added. That, along with the protection of language and democratic rights, was the whole point of the Resistance.

“(McDougall’s) language is that of the ruined and desperate politician and agitator, certainly not the statesman he was supposed to be at one time,” the newspaper wrote. “And it is well for the people of this country that Providence ordained he should never rule over them.”

If the lopsided vote in the House of Commons in favour of the Manitoba Act — proclaimed into law July 15, 1870, 150 years ago this month — was any indication, McDougall’s venomous remarks were not shared by a majority of Canadians at the time.

Nevertheless, racism and colonial mentalities were alive and well in 1870 Canada. As the people of Red River awaited the arrival of Lt.-Gov. Adams Archibald during that summer (and the military expedition on its way from Ottawa) they couldn’t help but feel some level of trepidation.

Would there be a peaceable transition of power? Would the federal government honour the property rights, land grants and other provisions contained in the Manitoba Act? Would Manitobans encounter bigoted, hateful views — like those of McDougall — from new settlers?

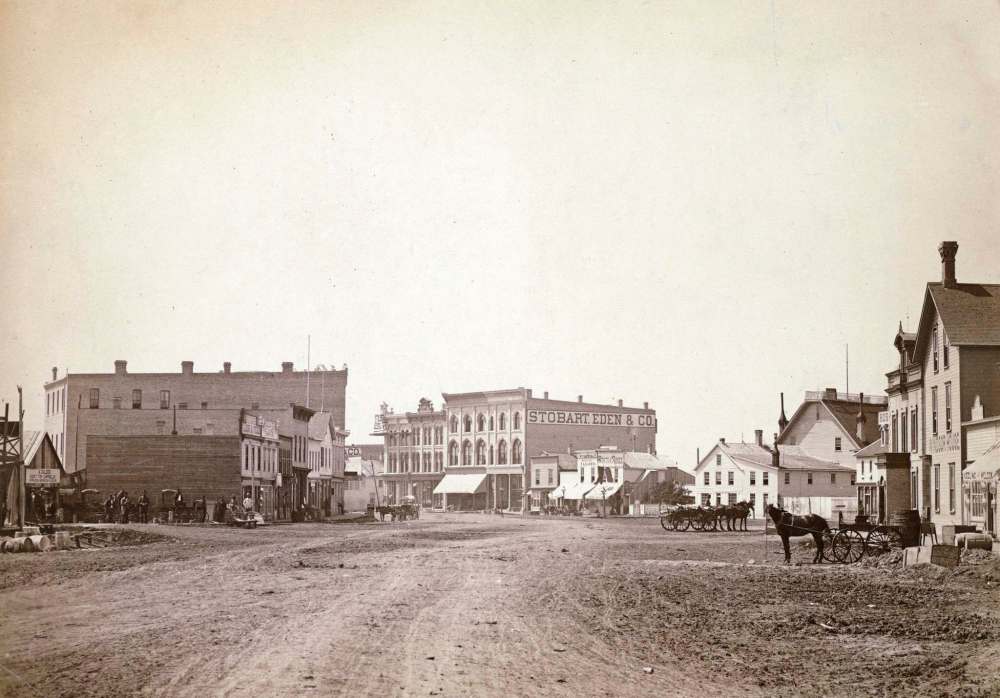

Manitobans were busy in the summer of 1870, farming and getting furs to market. More than 100 carts of buffalo robes, otter, mink, lynx, beaver and other furs from Winnipeg merchants Bannatyne & Begg were already on their way to St. Cloud, Minn. for shipment to various parts of the world. Two hundred more carts were expected to get to market that year.

There was a sense by many that joining Canada would take the settlement to new economic heights. A road from Lake of the Woods was nearing completion and the idea of a railroad from the east to Winnipeg was no longer an abstract notion. Regular mail would soon come to Winnipeg with three deliveries a week. Same-day telegraph service was less than a year away. Red River was about to graduate from a small frontier town with limited trading opportunities to one with access to broader markets in the east. Joining Canada was as much an economic union as a political necessity to protect the West from the threat of U.S. occupation.

Key players

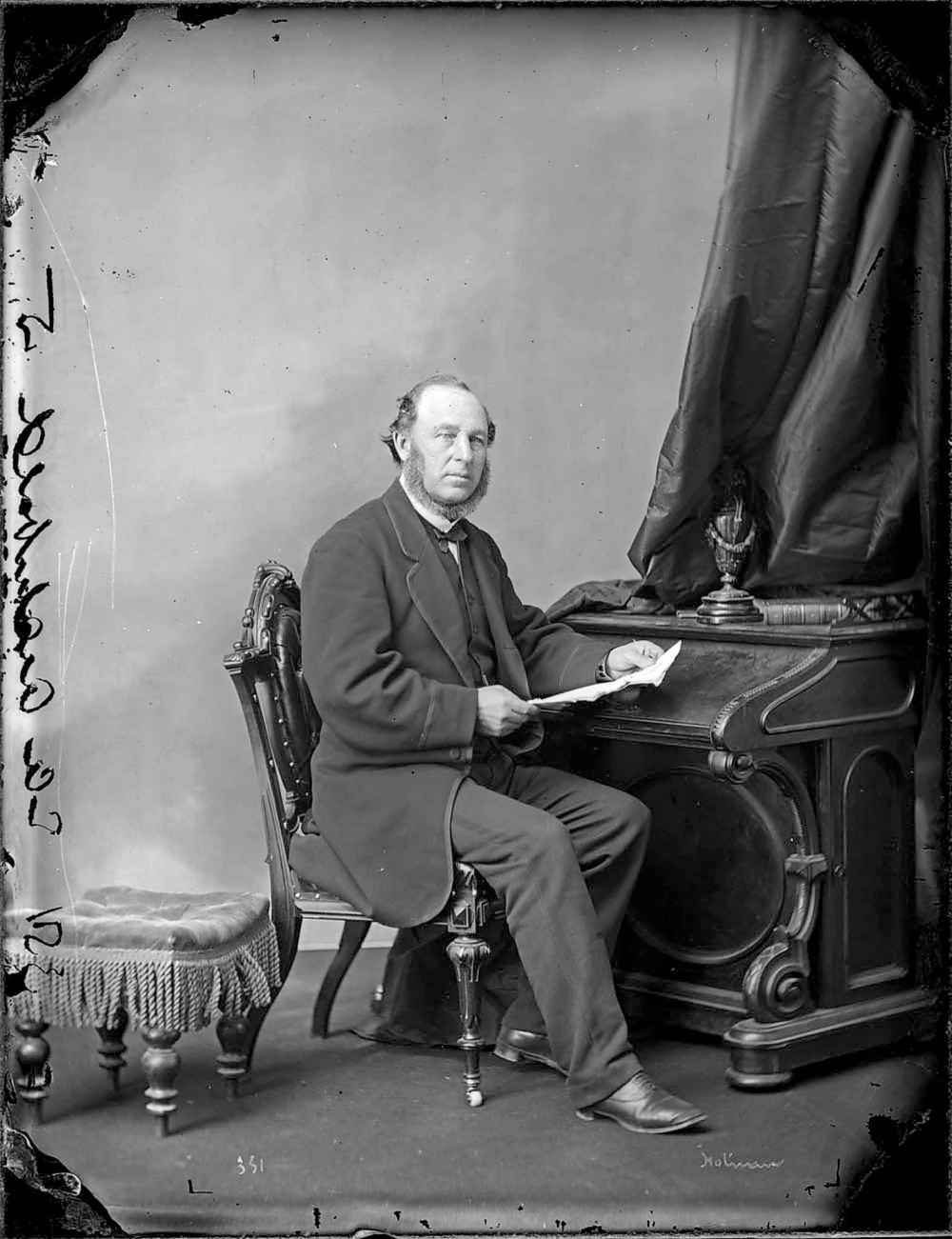

● Adams Archibald

Manitoba’s first lieutenant-governor. Born in Nova Scotia and a Father of Confederation, Archibald oversaw establishment of Manitoba’s legislative assembly and governed from 1870-73.

● Bishop Alexandre-Antonin Taché

Bishop of St. Boniface. Not present in Red River during most of the Red River Resistance, Taché fought for Métis rights and lobbied the federal government to make good on its promise to provide amnesty to those who participated in the Resistance, including Louis Riel.

● Adams Archibald

Manitoba’s first lieutenant-governor. Born in Nova Scotia and a Father of Confederation, Archibald oversaw establishment of Manitoba’s legislative assembly and governed from 1870-73.

● Bishop Alexandre-Antonin Taché

Bishop of St. Boniface. Not present in Red River during most of the Red River Resistance, Taché fought for Métis rights and lobbied the federal government to make good on its promise to provide amnesty to those who participated in the Resistance, including Louis Riel.

● Col. Garnet Wolseley

Field commander of the military expedition sent to Red River in 1870. Described Louis Riel and the Métis who established a provisional government in Red River and negotiated Manitoba’s entry into Canada as “banditti” that oppressed the people of Red River.

● Louis Riel

Métis leader who led the provisional government in Red River. Riel fled Upper Fort Garry when Wolseley’s troops arrived, fearing arrest and persecution. Riel remained in hiding for several years but was in contact with his people during that period. He convinced the Métis to join the fight against a planned Fenian raid.

● Elzéar Goulet

A Métis who was part of the Red River Resistance and a member of the tribunal that sentenced Ontario Orangeman Thomas Scott to death. Goulet drowned in the Red River after he was chased by Canadian militia volunteers who threw stones at him while trying to cross the river.

“We are glad to know that amongst their shipments there is a large one to Canada,” the New Nation wrote of the Bannatyne & Begg exports. “This is as it should be, for when we are united to the Dominion, trade will be the strongest tie to bind us together… Let Canada prove itself a good market for our exports, and she will derive thousands — we may say millions — of dollars from this country. We, on the other hand, will be large consumers of such articles as the merchants of the Dominion are in a position to furnish us.”

Not everyone in the East saw it that way, though. Some in Ontario were concerned the financial costs of inviting Manitoba into the constitutional fold would be a drain on the federal treasury.

The Hamilton Weekly Times wondered when the rest of Canada would benefit financially from the expansion, given the initial cost of buying Rupert’s Land from the Hudson’s Bay Company and the ongoing federal subsidies required for government administration, infrastructure, policing and transportation in Manitoba.

“What are we to get in return for all this large expenditure?” the newspaper asked in a July 14 article. “We shall have a vastly extended territory without doubt. The Dominion will embrace an area larger than that of the whole United States. But that will not necessarily bring in any return for the large amount of capital we shall be called upon to expend in various ways, upon our new purchase.”

Meanwhile, The New Nation was remarkably complimentary of John A. Macdonald, especially for a newspaper that served largely as an organ of Métis leader Louis Riel’s provisional government. Despite the prime minister’s attempt the previous year to unilaterally annex Red River without consulting its inhabitants, the newspaper praised him for ultimately doing the right thing by negotiating Manitoba’s terms of entry into Canada.

“As soon as he discovered the blunders into which his government had been led, regarding this country, he at once took steps to repair them in a statesman-like fashion,” the newspaper wrote.

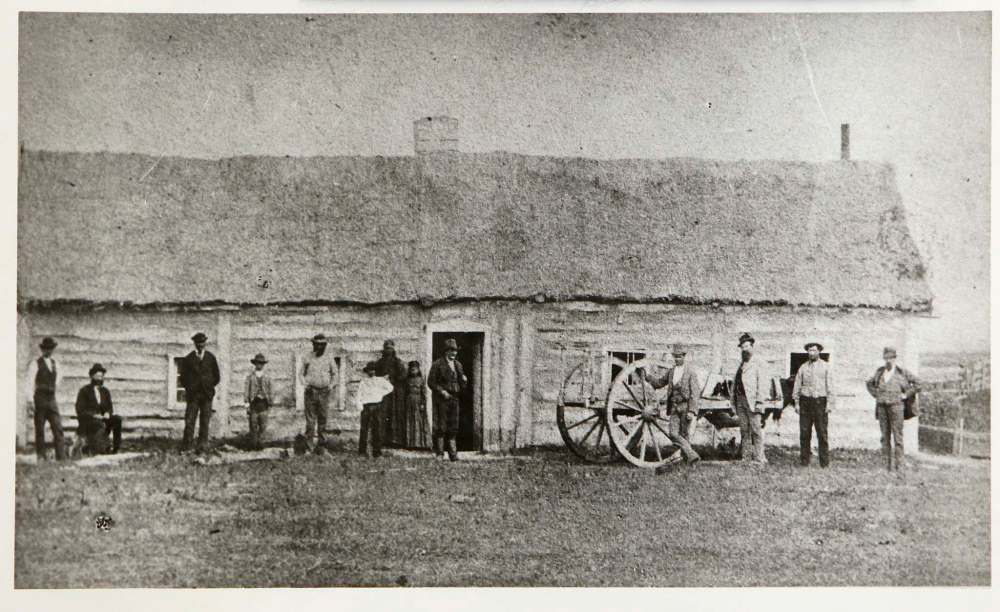

On some fronts, life was returning to normal in Red River after a bitter Resistance that pitted settler against settler. The constant fear of violent outbreaks while under martial law and the uncertainty about the future was over. The people of Red River were now Canadians.

But for many, particularly the Métis, the trust and faith they put into joining the federation would be severely challenged in the coming months and years.

Fears of antagonism and abuse from some Ontario settlers would soon prove true. It wasn’t long before the Canadian “loyalists” in Red River who fought the Métis resistance in 1869-70 (many of whom were jailed by the provisional government and exiled from the settlement) would soon get their revenge.

● ● ●

Four days after the arrival of Manitoba’s new lieutenant-governor, Adams Archibald, on Sept. 2, 1870, a mob of Canadian “loyalists” broke into the home of Thomas Spence, the publisher of the New Nation, tore him from his bed, horsewhipped him in front of his terrified wife and sabotaged the paper’s printing press.

It was the beginning of what became known as “the reign of terror” in the new province after the Aug. 24 arrival of military troops led by Col. Garnet Wolseley. Whatever goodwill grew out of talks between Red River delegates and the federal government earlier that year was now under threat.

John Christian Schultz, who administered the beating on Spence, was back in Red River after stirring up anti-Métis sentiment in Ontario during the spring and summer. Schultz and his “Canada First” supporters were now focused on seeking revenge against anyone who took part in the Red River Resistance, ridding the settlement of as many Métis as possible and clearing the way for new settlers from Ontario.

The New York Times, one of many newspapers from outside of Manitoba monitoring the events in Canada’s newest province, described the situation as a “military reign of terror in Manitoba.”

Even a year after his arrival, Archibald reported to the prime minister in stark terms the racism that existed in Manitoba.

“Unfortunately there is a frightful spirit of bigotry among a small but noisy section of our people,” Archibald wrote in a letter to Macdonald in October 1871. “The main body of the people have no such feeling — they would be only too happy to return to the original state of good neighbourhood with each other; but it is otherwise with the people I speak of, who really talk and seem to feel as if the French half-breeds should be wiped off the face of the globe.”

Archibald said the Métis had been so badly “beaten and outraged” they felt like “they were living in a state of slavery.”

Timeline

1870

● May 12

Manitoba Act receives royal assent.

● May-Aug

Louis Riel and the Legislative Assembly of Assiniboia govern Red River and await arrival of new lieutenant-governor.

● July 15

Manitoba Act proclaimed into law; Manitoba officially part of Canada.

● Aug. 24

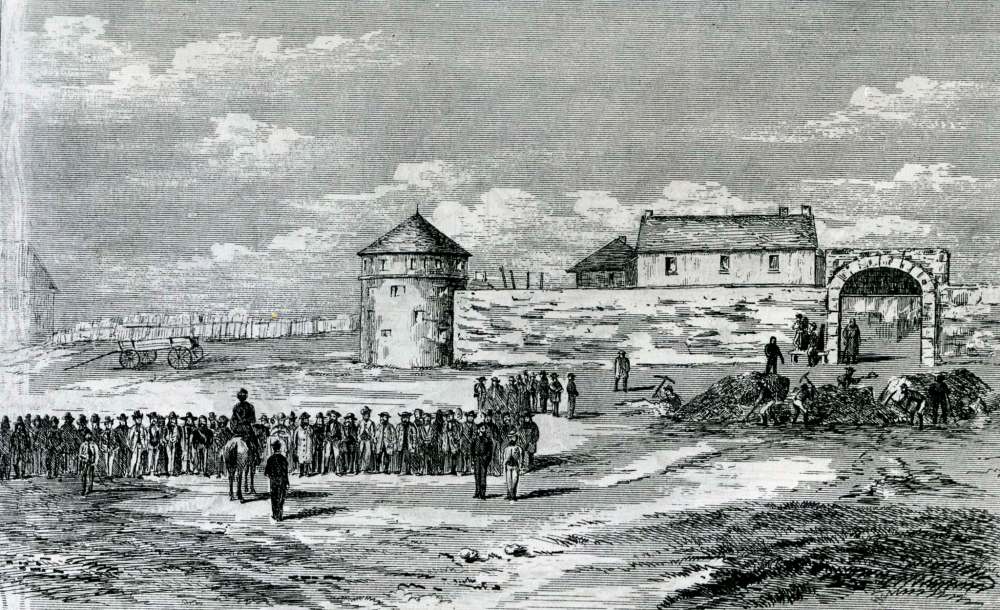

Col. Garnet Wolseley and the first British troops arrive at Upper Fort Garry, Riel and his supporters flee into hiding.

1870

● May 12

Manitoba Act receives royal assent.

● May-Aug

Louis Riel and the Legislative Assembly of Assiniboia govern Red River and await arrival of new lieutenant-governor.

● July 15

Manitoba Act proclaimed into law; Manitoba officially part of Canada.

● Aug. 24

Col. Garnet Wolseley and the first British troops arrive at Upper Fort Garry, Riel and his supporters flee into hiding.

● Sept. 2

Lieutenant-governor Adams Archibald arrives in Manitoba.

● Sept. 6

John Christian Schultz and supporters break into New Nation editor Thomas Spence’s home, attack him and sabotage newspaper’s printing presses.

● Sept. 13

Elzéar Goulet drowns after being chased into the Red River by Canadian militia.

● December

Elections held for first Manitoba Legislative Assembly.

1871

● March 15

First sitting of the Manitoba Legislative Assembly.

● October

Fenians plan raid of Manitoba, but invasion turns out to be a bust

Wolseley helped set that tone. He wrote several times about his desire to capture and punish Métis leader Louis Riel, even though the military expedition was supposed to be one of peace. Wolseley said he was disappointed the Métis didn’t resist his troops because it deprived his men of a good battle. Even though George-Étienne Cartier (the federal government’s key cabinet negotiator) called on Riel and the legislative assembly of Assiniboia to continue governing the settlement until the arrival of the new lieutenant-governor, Wolseley treated the provisional government as enemies of the state.

In a written valedictory address, which was read to the Canadian troops shortly after Wolseley and his British soldiers left the settlement in September, Wolseley stoked the flames further with disparaging comments about Riel and the provisional government.

“Although the banditti who had been oppressing this people fled at your approach without giving you an opportunity of proving how men capable of such labor could fight, you have deserved as well of your country as if you had won a battle,” he wrote.

Schultz was the chief antagonist in Red River in 1870. By shutting down the local paper and starting his own, called the News-Letter, Schultz sought to control the political messaging in the new province. However, the monopoly didn’t last long. Longtime journalist William Coldwell co-founded The Manitoban the following month, using the restored New Nation printing presses. It marked the beginning of a bitter newspaper war that lasted well into the following year.

For his part, Archibald — a Nova Scotian and a Father of Confederation — had a daunting task ahead of him. He had to calm the hostilities between pro-Riel and anti-Métis forces while building a new government with an elected legislative assembly and an appointed senate. He needed a police force, new laws and the co-operation of all factions in the new province to make it work.

Archibald was far more sympathetic to the plight of the Métis than McDougall would ever be. The new lieutenant-governor had a good read on the complexities of Red River and understood the competing demands within the settlement. What he wasn’t able — or refused — to do was crack down on the persistent attacks against the Métis, including by members of the Canadian militia left behind by Wolseley.

“During the fall and early winter of 1870 we could always rely on several exciting fights between the soldiers and Half Breeds any afternoon after three o’clock, by which hour the soldiers who were not on duty at the garrison were at liberty to come downtown.” – St. Paul Press, March 1871

The death of Elzéar Goulet two weeks after the arrival of Wolseley’s troops is the most documented act of violence against the Métis. Goulet drowned after he was chased by Canadian militia volunteers, who threw stones at him as he tried to swim across the Red River. Archibald ordered an investigation, but no one was ever held accountable for Goulet’s death.

Very little of the violence against the Métis was reported in either of the local newspapers — the News-Letter, for obvious reasons, and The Manitoban, for less-obvious ones. However, many papers from outside the province, including from Minnesota, Quebec and Ontario, did carry reports of the so-called reign of terror.

Some sent correspondents to the settlement to witness the developments first-hand.

“During the fall and early winter of 1870 we could always rely on several exciting fights between the soldiers and Half Breeds any afternoon after three o’clock, by which hour the soldiers who were not on duty at the garrison were at liberty to come downtown,” wrote the St. Paul Press in March 1871.

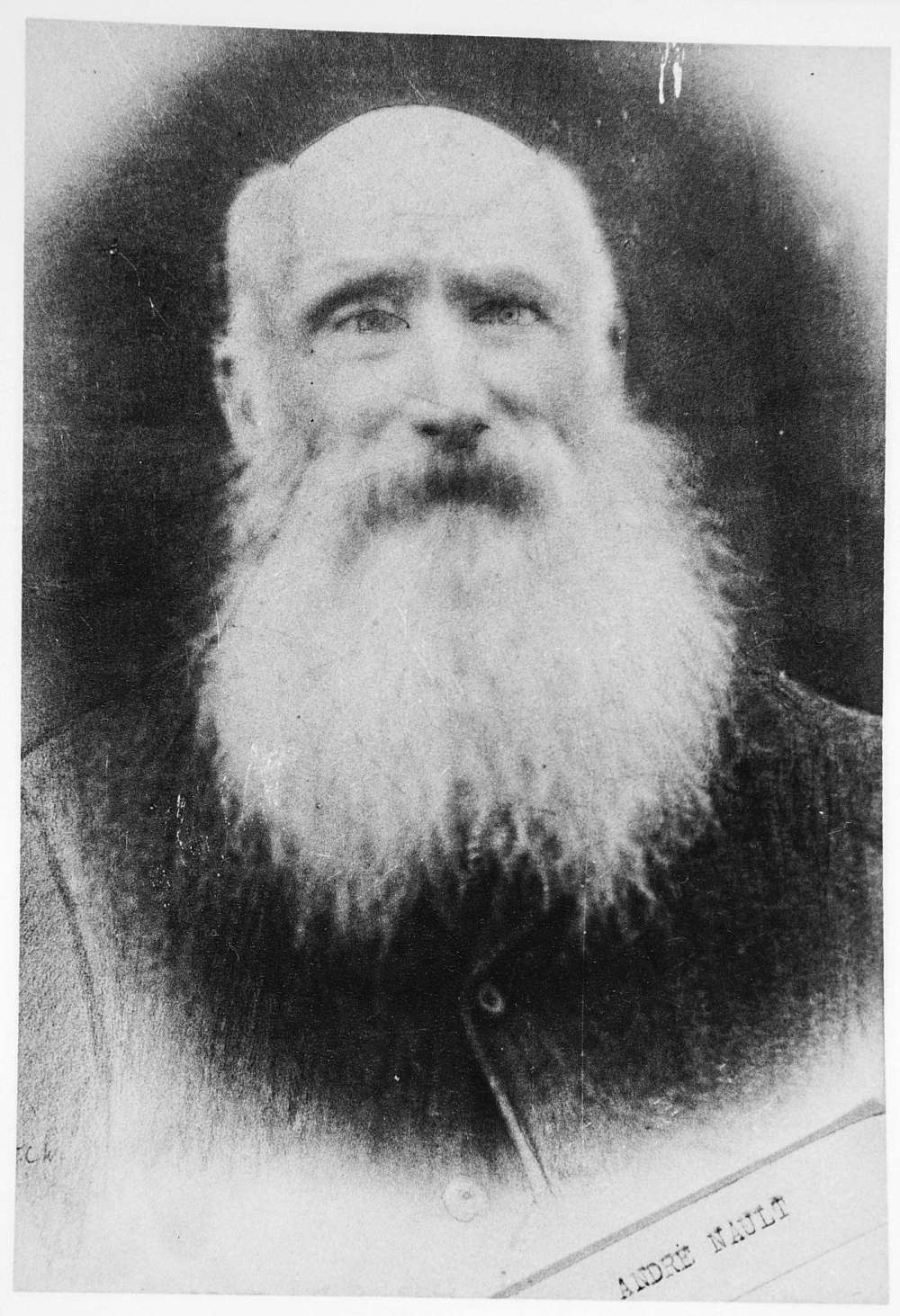

The list of reported attacks against Métis residents after the arrival of Wolseley’s troops is long. Andre Nault, who played a significant role in the Resistance, was chased and beaten nearly to death in Pembina by Canadian militia soldiers in March 1871.

In December 1870 James Tanner, a prominent English Métis, was killed after two unknown assailants startled his horse, causing him to be thrown from his buggy. He fractured his skull and died of his injuries.

There was a report of a Métis named Landry who was attacked by soldiers outside Upper Fort Garry in November 1870. Soldiers allegedly put a noose around his neck and dragged him several hundred feet. According to the report, he may have died had his son not alerted police.

James Ross, one of the key leaders among the English Métis during the Resistance, had his unoccupied, two-storey house in Winnipeg torched by unknown arsonists (witnesses saw the fire start at both ends of the house).

Bob O’Lone, an American who was a member of the provisional government, died after a blow to his head from a revolver in a barroom brawl.

The Quebec newspaper La Minerve reported that Métis Louis Hibbert from the Qu’Appelle Lakes, who came to Manitoba, was assaulted by soldiers and beaten with belts. He may have been killed if two women had not intervened. Two newcomers from Ontario are quoted in the newspaper saying the brutality by soldiers against local residents was far worse than they had heard about.

In December 1871, a group of armed Canadian militia volunteers barged into the home of Louis Riel’s mother, looking for the Métis leader (who was still in hiding), and threatened his family.

Archibald provided testimony on the home invasion at an 1874 House of Commons select committee hearing on the causes of the Resistance.

“A party of some eight or ten disbanded volunteers had, without warrant, made a raid on the house of Riel’s mother, with faces masked and armed with revolvers, when they committed outrages that had excited the French half-breeds almost to a frenzy,” he said.

Archibald laid out the problems of violence against the Métis in broader terms in a November 1871 memorandum. The report provided further evidence that one of the reasons many Canadians enlisted in Wolseley’s expedition was to avenge the death of Thomas Scott, the Ontario man executed by the provisional government in March 1870.

“Some of them openly stated that they had taken a vow before leaving home to pay off all scores by shooting down any Frenchman that was in any way connected with that event,” Archibald wrote. “When the volunteers came to be disbanded, and were thus freed from all restraint, the hatred of the two classes exhibited itself more and more. Some of the immigrants from Ontario shared the feelings of the disbanded volunteers, and acted in concert with them.”

“Can anything more scandalous be conceived than this constant and persistent inciting to violence and mob law?” – The Manitoban

Even The Manitoban, which was largely a pro-government newspaper, grew frustrated with the violence in the settlement and blamed Schultz and his supporters for the unrest.

“Can anything more scandalous be conceived than this constant and persistent inciting to violence and mob law?” the newspaper wrote.

Still, it wasn’t all bad in the early days of Manitoba. There were many reports of life improving for local residents — French and English — and a return to the festive lifestyle many enjoyed prior to the resistance.

Joining Canada brought greater political and economic stability to the region. Although many would be left out, Manitobans were starting to see a brighter future ahead.

Métis stepped up for Crown, got stepped on for their trouble

Just as life was returning to normal for many Manitobans in the fall of 1871, a new threat emerged that could have ended in bloodshed. Instead, it turned out to be a unifying event for the new province — albeit a brief one. It demonstrated that during a crisis, when their community was under threat of attack, Manitobans could put their differences aside and stand together.

Rumours of a Fenian raid from the United States began circulating in September 1871, raising fears that Manitoba may not be able to protect itself from a military invasion. The volunteer militia from Canada that was part of the Wolseley expedition was disbanded earlier that year. Only a small garrison was stationed at Upper Fort Garry. The threat of hundreds — perhaps thousands — of Fenian Brotherhood soldiers crossing the border into Manitoba became a serious threat that sent a chill through the Red River Valley.

The Fenians — Irish-Americans who had made several failed attempts to invade parts of Eastern Canada following the U.S. Civil War — sought to occupy Canada (or British North America prior to 1867) as leverage for an independent Ireland. Manitoba, with no regular troops and only a small police force, seemed an easy target. The would-be invaders also hoped to convince disgruntled francophone Métis to join their cause, not only to bolster their ranks but to weaken Manitoba’s line of defence.

Just as life was returning to normal for many Manitobans in the fall of 1871, a new threat emerged that could have ended in bloodshed. Instead, it turned out to be a unifying event for the new province — albeit a brief one. It demonstrated that during a crisis, when their community was under threat of attack, Manitobans could put their differences aside and stand together.

Rumours of a Fenian raid from the United States began circulating in September 1871, raising fears that Manitoba may not be able to protect itself from a military invasion. The volunteer militia from Canada that was part of the Wolseley expedition was disbanded earlier that year. Only a small garrison was stationed at Upper Fort Garry. The threat of hundreds — perhaps thousands — of Fenian Brotherhood soldiers crossing the border into Manitoba became a serious threat that sent a chill through the Red River Valley.

The Fenians — Irish-Americans who had made several failed attempts to invade parts of Eastern Canada following the U.S. Civil War — sought to occupy Canada (or British North America prior to 1867) as leverage for an independent Ireland. Manitoba, with no regular troops and only a small police force, seemed an easy target. The would-be invaders also hoped to convince disgruntled francophone Métis to join their cause, not only to bolster their ranks but to weaken Manitoba’s line of defence.

Irish-born William O’Donoghue — once a key player in Louis Riel’s provisional government — was behind the planned attack. Now in exile for fear of arrest, O’Donoghue, who had a falling out with Riel, was hoping to recruit enough Métis to topple whatever forces the Manitoba government could marshal. But to do so, he would need the backing of Riel, who, although himself also in hiding for fear of arrest, still wielded considerable influence over his people.

By Oct. 3, the threat of invasion was real enough that Lt.-Gov. Adams Archibald issued a proclamation calling on citizens to form a militia to protect their homeland. There was no confirmation on how many Fenians might cross the border. But the threat was taken seriously because of the large number of Fenians in the U.S., many of whom fought in the Civil War and had military experience.

“We call upon all our said loving subjects, irrespective of race or religion, or of past local differences, to rally round the flag of our common country,” Archibald wrote in the proclamation. “The country need feel no alarm. We are quite able to repel these outlaws… Rally, then, at once! We rely upon the prompt response of all our people of every origin…”

Hundreds of Manitobans signed up immediately and a battalion of 200 men was sent to the border. However, the invasion turned out to be a bust. Rumours of a large Fenian contingent proved false. On Oct. 5, only about 40 armed men crossed into Manitoba, some of them Irish-Americans. They were arrested almost immediately by U.S. cavalry. The raid wasn’t even sanctioned by the Fenian Brotherhood.

However, Archibald didn’t know that at the time. Because there were still fears of a larger invasion, the lieutenant-governor sought the support of the Métis to help repel a possible second raid.

Métis support wasn’t necessarily a given, considering the abuse many continued to endure at the hands of former Canadian militia volunteers and newcomers. The land allotments promised by the federal government had still not materialized more than a year after the Manitoba Act was proclaimed into law. And the amnesty promised for those involved in the Resistance — including Riel — remained stalled. Riel was also concerned he could be arrested, or worse, if he showed himself in public, a fear Archibald addressed by getting word to the Métis leader that if he fought for Manitoba, he would not be detained.

Despite the risks, and the fact Riel had been deceived by federal officials more than once since the passage of the Manitoba Act, the Métis leader eventually agreed and convinced hundreds of his people to assemble in St. Boniface.

“Several companies have already been organized, and others are in the process of formation,” Riel wrote in a letter to Archibald. “So long as our services continue to be required, you may rely on us.”

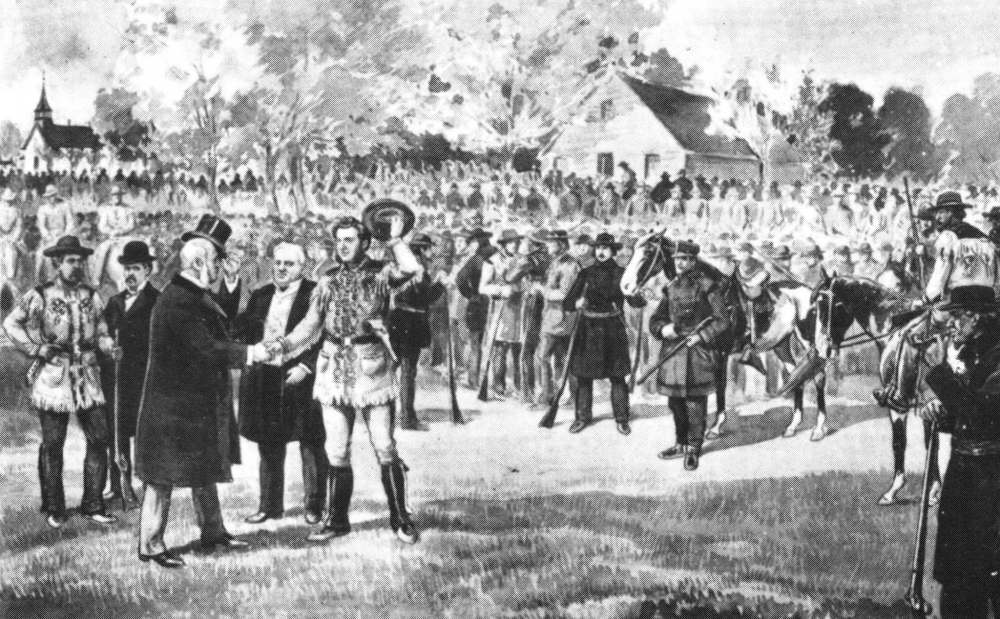

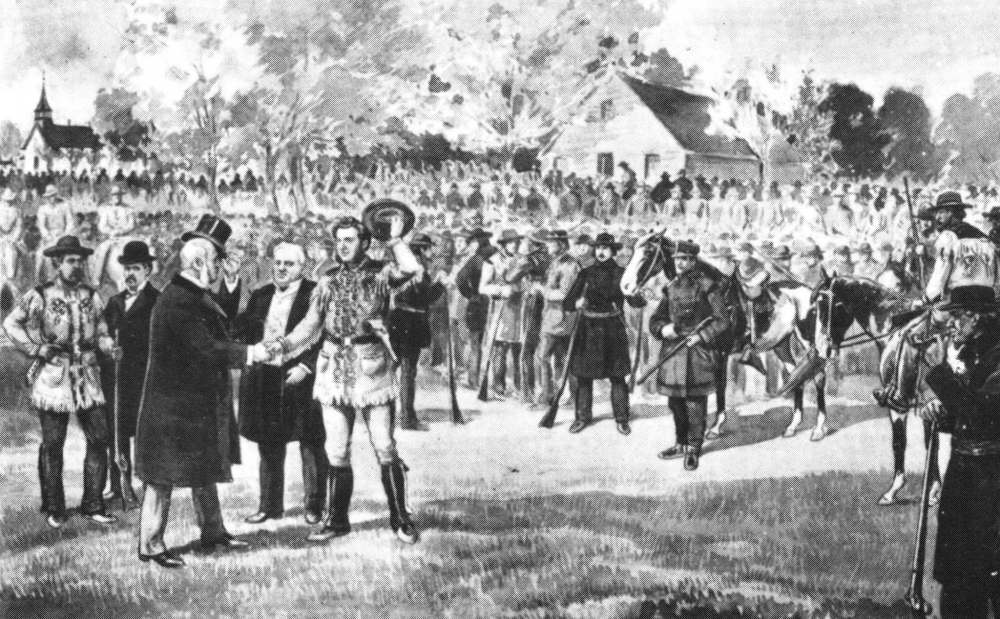

Archibald was invited to inspect the Métis troops in St. Boniface, which he did on Oct. 8. It’s believed he shook Riel’s hand during the inspection, a show of conciliation that rankled the anti-Riel crowd, including some in Eastern Canada.

“I found assembled on the bank 200 able-bodied French Métis; of these 50 were mounted, and a considerable part of the whole body had firearms,” Archibald later wrote.

The Métis cheered and told the lieutenant-governor they had “rallied to the support of the Crown, and were prepared to do their duty as loyal subjects in repelling any raid that might now, or hereafter, be made on the country.”

Archibald assured the Métis that their show of loyalty would be communicated to the governor general in Ottawa.

Fortunately for Manitoba, there were no more raids. Those arrested by U.S. officials were eventually released, including O’Donoghue. Three Métis from Pembina who had joined the botched raid were arrested in Manitoba, although only one was ever convicted.

Even though the Fenian threat turned out to be of little consequence, Archibald praised those who came together to protect their homeland.

“We gave proof to the invaders and to the world that, differ as we might among ourselves on matters of minor moment, our hearts were right and our hands ready when duty called us to the defence of our common country,” Archibald wrote in a summary of his first year in office.

The loyalty shown by Riel and the Métis wasn’t reciprocated by the federal government, though. There was still no amnesty, the distribution of 1.4 million acres of land promised to Métis families continued to be delayed, newcomers were snapping up some of the most valuable land in the valley and Riel and Ambrose Lépine, the adjutant-general in the provisional government, were forced to retreat back into hiding after the threat of the raid subsided. Many Métis were still facing abuse and physical attacks in the streets of Winnipeg.

It’s something Bishop Alexandre-Antonin Taché, who was in frequent contact with Ottawa about the mistreatment of the Métis, pointed out in several blistering letters to federal cabinet minister George-Étienne Cartier.

“You do not know all the affronts, privations and even bad treatment we have endured,” he wrote in one letter. “Amidst all this, we have kept the profoundest silence, and we have refrained from making known, even to our friends, what was taking place here, in order not to create difficulties for the Ottawa Government.”

If threats of a Fenian raid helped unite Manitoba in 1871, it didn’t do much for the long-term interests of the Métis. Whatever loyalty they showed during the crisis was soon forgotten. The Fenian raid, and the willingness of the Métis to join forces with the Crown, ended up being little more than a footnote in Manitoba history.

— Tom Brodbeck

Local francophones would get their own newspaper in 1871, called Le Métis. And many who had taken part in the provisional government a year earlier were elected to the new legislative assembly, or appointed to high-profile positions.

The frequent Red River celebrations that were largely paused during the uprising of 1869-70 were starting to return.

“A gayer, a happier, a more jovial people do not exist anywhere, than the people on both sides of the Red River,” the Manitoban wrote in January 1871. “Every night of the week we hear of balls here and balls there, and balls almost everywhere…. When the dancing has once begun there is no stopping it. On it goes, one set after the other, without cessation or intermission; and the fiddlers, as if catching the general elation of spirits, fiddle as if for very life.”

Like most aspects of the Red River Resistance and the early days of Manitoba, the story differs depending on whose perspective it’s told from. For recent arrivals, Canada’s newest province represented opportunity; to farm, to trade, to own land and raise a family. For some of the old settlers, including many anglophones and some English Métis, joining Canada meant stability, economic growth and the benefits of being part of a larger nation-state. But for many Métis, anglophone and francophone, it meant oppression; a loss of self-determination and dignity. Canada’s vision was to populate the West with white settlers — a vision that didn’t include Métis or First Nations inhabitants, many of whom suddenly felt unwelcome in their own land.

Not everyone shared equally in the benefits of Confederation. That is part of Manitoba’s legacy as it looks back over 150 years of history.

tom.brodbeck@freepress.mb.ca

Tom Brodbeck is an award-winning author and columnist with over 30 years experience in print media. He joined the Free Press in 2019. Born and raised in Montreal, Tom graduated from the University of Manitoba in 1993 with a Bachelor of Arts degree in economics and commerce. Read more about Tom.

Tom provides commentary and analysis on political and related issues at the municipal, provincial and federal level. His columns are built on research and coverage of local events. The Free Press’s editing team reviews Tom’s columns before they are posted online or published in print – part of the Free Press’s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

![Thomas Scott (c. 1842 – 1870) was an Irish-born Canadian and fervent Orangeman. Scott was born in the Clandeboye area of County Down, in what is now Northern Ireland.[1] He was recruited by Canada to fight in the Red River Rebellion and was captured and imprisoned in Upper Fort Garry by Louis Riel and his men while trying to attack it along with 34 other volunteers. Scott made an attempt to escape but was recaptured by Riel's men and was summarily executed for committing insubordination. Scott's execution led to an outrage in Ontario, and was largely responsible for prompting the Wolseley Expedition, which forced Louis Riel, now branded a murderer, to flee the settlement. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Scott_%28Orangeman%29](https://dev.winnipegfreepress.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2022/05/Thomas+Scott.jpg?w=100)