Grim COVID-19 milestone was inevitable

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 12/05/2021 (1673 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Manitoba crossed a distressing but long-anticipated threshold on Wednesday when it recorded its 1,000th COVID-19-related death. Regardless of the context in which one chooses to view it, that number stands as an indictment of both the virulence of the novel coronavirus and — equally — our collective failure to manage the threat it represents.

COVID-19 has, in many ways, presented an unprecedented public-health challenge. Many have drawn a parallel to the 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic; despite misinformed claims to the contrary, however, the coronavirus is not like influenza. Its basic characteristics are fundamentally different and the tools and methods required to control it must be, as well.

The latter consideration is where Manitoba, as well as numerous other jurisdictions around the world, has failed. No one could have prevented COVID-19 from reaching pandemic proportions. But the decisions made and the methodologies applied in response have most certainly made what was destined to be a bad situation much worse.

Manitoba did show early promise. Its decision to lock down the province on April 1, 2020, with no exceptions, helped make this one of the most successful jurisdictions in the world at controlling the spread of COVID-19. But that experience with severe social and economic restrictions seemed to somehow dull our appetite for taking a hard line against the coronavirus.

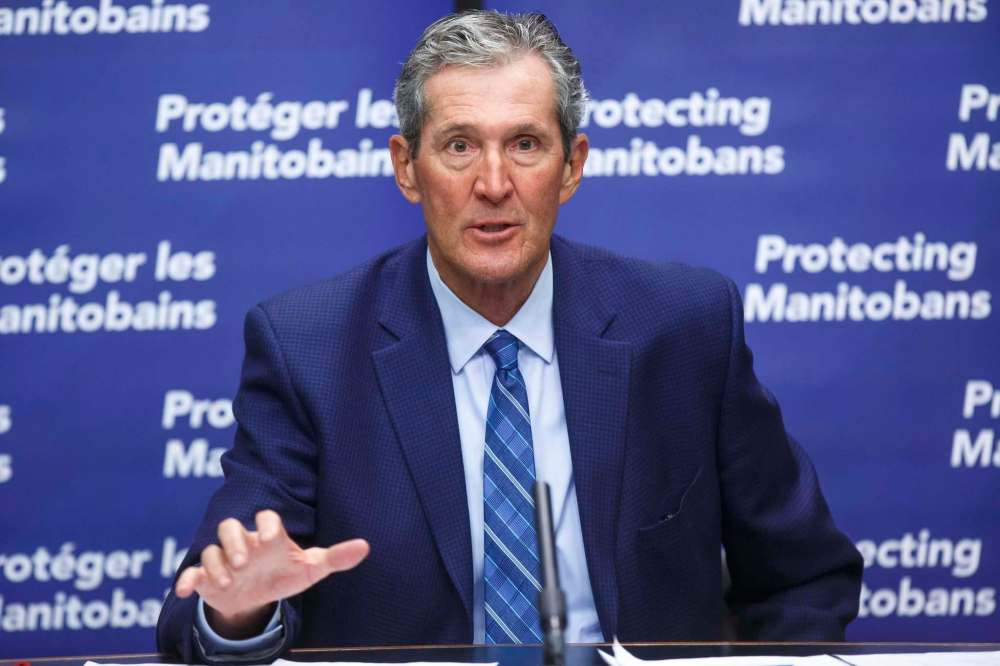

In subsequent waves, Premier Brian Pallister and his government have appeared reluctant, perhaps even averse, to applying the short, sharp lockdowns that other countries have used to extinguish outbreaks. The result has been an overall pandemic response strategy that, in epidemiological terms, has been largely a failure.

Last fall and again during the current COVID-19 upsurge, the Pallister government has allowed case numbers and hospital admissions to rise to alarming levels with only modest responses. The government has described this strategy as applying the “least-restrictive means” to address surges in viral infection.

In steadfastly adhering to this rationale for public-health intervention, Manitoba has essentially conceded that severe second and third waves of COVID-19 were inevitable. Such an approach unacceptably ignores the experience in other countries that have done a much better job at containing COVID-19 and, in so doing, largely spared their people from extended social and economic restrictions.

New Zealand is among a handful of countries that have demonstrated a different and decidedly more effective way of managing the coronavirus. Severe lockdowns last spring were followed by very tight restrictions on travel into and within the country. However, the smartest thing New Zealand has done is to respond with the full force of social and economic restrictions at the first sign that community transmission of the virus was occurring.

And when he wasn’t imposing half-measures, Mr. Pallister seemed inclined to grant concessions to select businesses or constituencies based on criteria that seemingly ignored the science and relied almost entirely on politics.

Manitoba, by comparison, has continued to tinker with relatively modest restrictions even when case counts showed signs of exploding. And when he wasn’t imposing half-measures, Mr. Pallister seemed inclined to grant concessions to select businesses or constituencies based on criteria that seemingly ignored the science and relied almost entirely on politics.

Given all that, there was no opportunity for this province to escape the currently unfolding horrors of COVID-19. The way the virus has spread around the globe, expecting no deaths would be tantamount to walking through a rain storm and expecting not to get wet.

But Manitoba could have — and, arguably, should have — managed the pandemic in a way that ensured fewer than 1,000 of its citizens lost their lives. The failure to do so leaves all Manitobans, from government on down, to grapple with the awful knowledge that many of those who have died did so unnecessarily.