Reprise for automatic keys Player pianos take pride of place for modern aficionados

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 12/05/2021 (1671 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

From pogo sticks to baking clubs, everything old is new again — including the grandes dames of the instrumental world, player pianos — evoking kinder, gentler times of bygone years.

However, some diehard fans would argue the “reproducing” or “mechanical” piano never really did go out of style since its glory days of the 1920s, offering original in-house entertainment before new-fangled radios and phonographs roared into living rooms, and light-years before the dawning of now-ubiquitous digital technology.

One of those aficionados is Winnipeg arts executive/musician Andrew Thomson who has nurtured a passion for the “pianola” since becoming smitten at age “10 or 11” by a player piano transported to his family’s Whytewold cottage. The instrument badly in need of TLC had been moved from Great-West Life Assurance Company, where his grandfather, W. Davidson Thomson, had once worked as a head cashier and served as social director, which included leading its then in-house choirs.

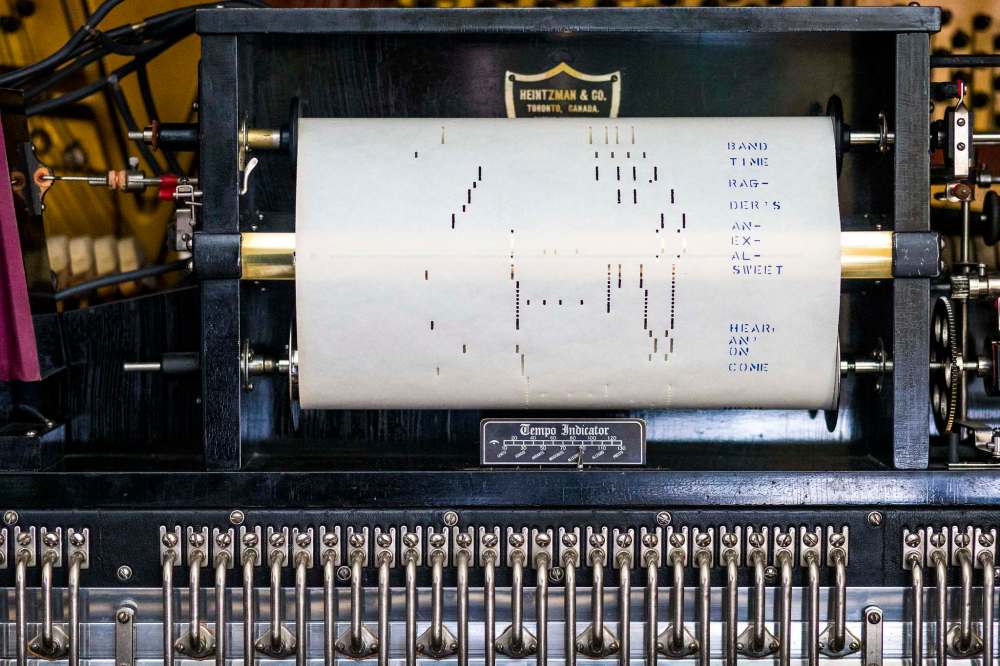

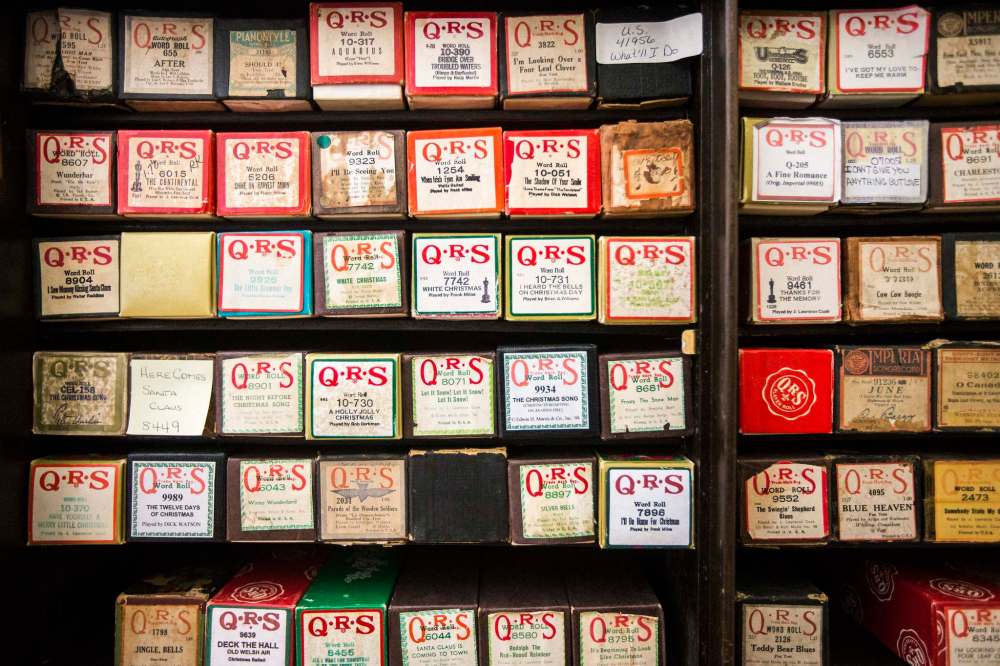

Fast forward 50-ish years later, and that same piano – a 99-year-old Heintzman – is now a part of his collection of four pianos that also includes a stately, century-old “Apollo” player grand he keeps at his East Kildonan bungalow. Thomson also maintains a carefully curated library of 650 (and counting) piano rolls that provides grist for the player piano’s mechanical guts.

‘I’ve always been able to take things apart and put them back together again,” says Thomson, who serves as executive director of the Virtuosi Concerts and son of highly respected Winnipeg musicians, the late Stewart Thomson and Phyllis Thomson. “This piano intrigued me and I decided that one of the kids from my dad’s church choir, Duncan Campbell, and I were going to put it back together again.”

He recounts working on the instrument with his childhood chum well into the wee hours, thrilled to hear the melodious first strains of Irving Berlin’s Alexander’s Ragtime Band wafting across the lake at 1 a.m. after getting the piano back in fighting trim.

“A neighbour came over the next day to say she was going to tell us to stop. But then she thought it was my dad playing and decided to let it go,” he recalls with a chuckle. Buoyed by their success, Thomson picked up several more rolls including Simon and Garfunkel 1970s hit tune Bridge Over Troubled Water and a groovy ‘60s rendition of Aquarius (Let the Sunshine In) at long-defunct J.J.H. McLean’s downtown music store, further fuelling his “absolutely crazy” passion that continues to this day.

Player pianos essentially come in two “flavours”: newer electric instruments, or traditional “pumpers,” in which a player manually paddles air with their feet via pedals, in turn pneumatically rotating the song roll to magically depress the piano keys. Perforated holes punched into the paper rolls typically “tell” the piano which notes to play via a coding system, as well as when, for how long, and at what dynamic level. It’s an astonishing feat of engineering that makes many modern-day inventions look like child’s play.

Pumpers are resolutely acoustic instruments including actual hammer strikes on the piano strings, with nary a plug-in cord to be seen. A doppelganger, the “nickelodeon” earned its nickname after being placed in popular establishments to have music lovers plugging nickels into a slot to hear their favourite tunes, arguably a prototype for the jukebox.

And it’s not just all ragtime either; with a full spectrum of music ranging from classical chestnuts to Broadway show tunes, gospel numbers and more. There are even rolls that simply provide piano accompaniments for singers, including full-bore family sing-alongs and instrumentalists, as well as entire, extended concertos performed by four-hand piano — those rolls are extra-thick, doubling up to three inches, Thomson notes — to enjoy from the comfort of one’s own home.

At their zenith in 1924, and before the stock market crash of 1929 sounded the death knell for production all around the world, a player piano typically cost the princely sum of $250, equivalent to around $8,000 in today’s dollars, with individual rolls that might include a playlist up to 10 songs ringing in at $5-6 dollars per piece. Picking up a pianola today can range from freebie giveaways to hundreds of dollars. Thomson snapped up his prized Apollo for a song that came with boxes of antique rolls, paying US$800 after driving down to La Crosse, Wis., to bring his treasure home back in 2013.

In addition to the joy-sparking, novelty factor in bringing music from the past to life again, player pianos serve another important, even historical function. If you’ve ever wondered how exactly George Gershwin might have wanted his famous Tin Pan Alley tune Fascinating Rhythm to sound, or Rachmaninoff’s Rhapsody on a Theme by Paganini, look no further than your nearest player piano roll. Many 20th-century composers/pianists also including Mahler, Faure, Strauss and Debussy recorded their own music for posterity, which gives modern-day listeners a front-row seat to their creative process.

Another avid collector in the city is Alan Turner, a past president of the Automatic Musical Instrument Collectors’ Association (AMICA), who proudly owns 15 player pianos, including two he’s currently storing for friends. The international group based in the U.S. notably held its 37th annual convention — currently on hiatus during the global pandemic — at Winnipeg’s historic Fort Garry Hotel in August 2017, that saw approximately 100 attendees out of its global ranks of “1,000 to 2,000” members throng here from Australia, Europe and beyond to share their love for the instrument.

Turner, a retired engineer, not to mention a recipient of AMICA’s “Footsie” award for best pumper piano, told Free Press writer David Sanderson that year he first became fascinated by player pianos at age nine or 10, after his parents took him to visit his uncle’s hobby farm near Brandon. He never forgot the thrill of seeing his first player piano up close, nestled into a corner and eventually purchased his own instrument much later in 2002. His collection also includes 1,500-2,000 rolls he stores in a bedroom in his Crescentwood home.

His personal favourite is a rare, Steinway 6-foot-2 grand piano dated 1924 taking pride of place in his living room, Turner says during a telephone interview last week. It’s also one of four or five player grand pianos he owns with several of the massive instruments simply stored on their sides for practical reasons.

“I think it’s got a beautiful sound, but it needs work,” Turner, who admits he plays a “mean chopsticks,” states matter-of-factly, adding that he’s always been drawn to player pianos for their “mechanisms, design and the engineering that went into that” and owns several other mechanical instruments including an ingenious, 100 plus-year-old “orchestrion,” which is essentially an orchestra in a box, that includes, in this case, a player piano, xylophone, tambourine and maracas. It’s like a pianola on steroids.

It’s a no-brainer that many player piano fans are growing long in the proverbial tooth, with plenty of pumpers still in existence eventually needing a new forever home; a challenge when younger generations aren’t exactly scooping up these vestiges of the past anytime soon.

Thomson offers advice for the curious, and potential future collectors who might wish to dip their fingers and toes — and feet — into the world of mechanical pianos.

“You just begin, and it behooves any of us that are into player pianos to encourage other people to see what they can do. We need to give those who might be interested in starting their own collection an opportunity to talk about them, play them and experience these wonderful instruments for themselves,” he says. “You never know what will happen.”

Holly.harris@shaw.ca