‘Someone’s gotta say something sooner or later’ Impact of unsolved North End shooting spree ripples decade later

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 22/10/2020 (1879 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Crime and violence are no strangers to Winnipeg’s North End. But on Oct. 23, 2010, the sound of gunfire, screams and sirens signalled one of the neighbourhood’s darkest nights in memory.

Over the course of 45 minutes, three people were shot at different locations; two died.

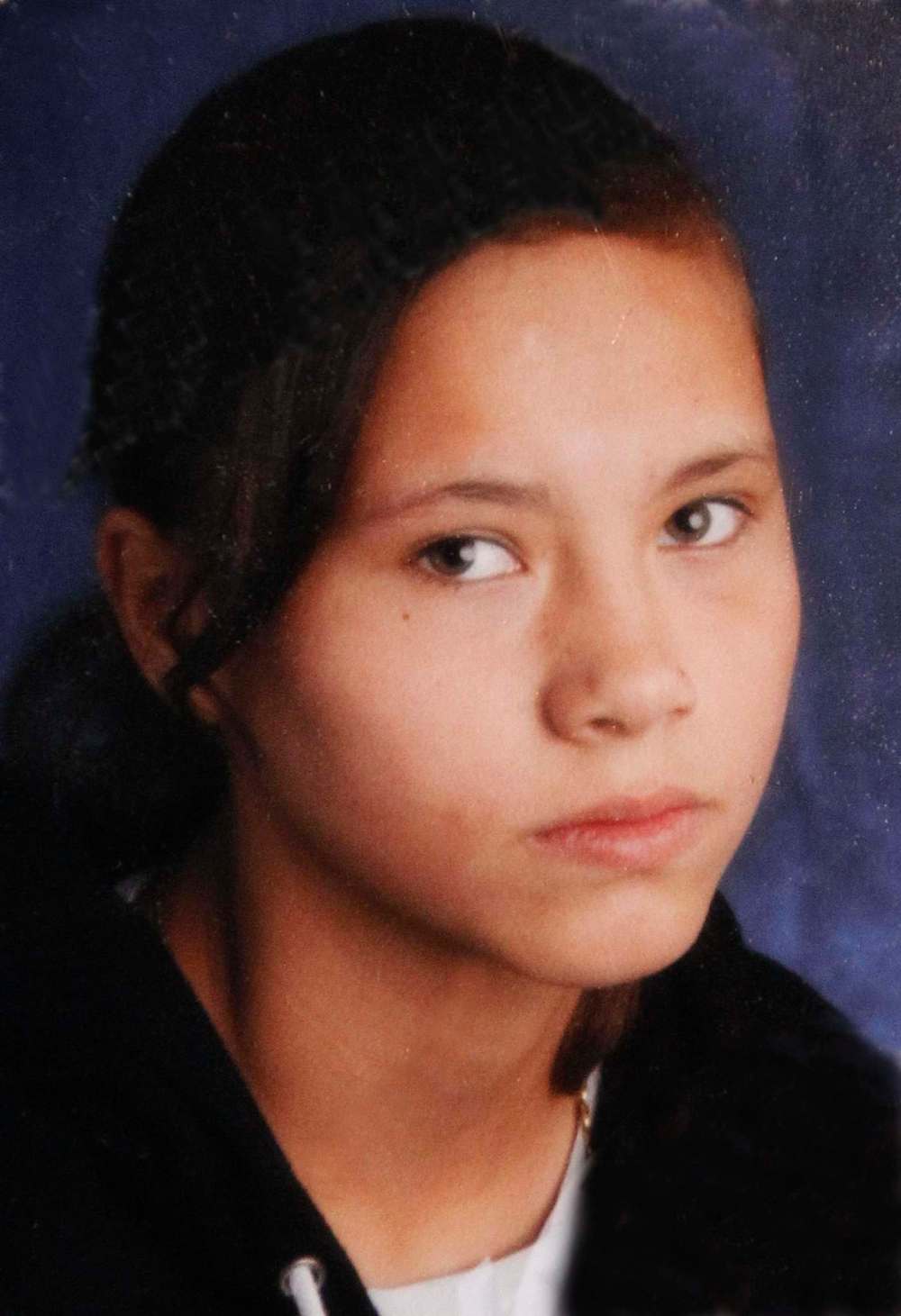

Samantha Stevenson, 13 at the time, was the first to be shot, and was the lone survivor. Samantha was walking at the Lord Selkirk Park Housing Development around 8:30 p.m., when she was wounded by a masked male on a bicycle.

Ten minutes later, Thomas Beardy, a 35-year-old father of four, was shot dead at the back door of a home he was visiting on Dufferin Avenue.

Thirty-five minutes after that incident, a shot rang out several blocks to the north on Boyd Avenue. Ian MacDonald, 52, was killed after answering a knock at the door of his bungalow home.

There are no known connections between the three victims. A decade later, no one has been arrested for the crimes.

Winnipeg police this month declined comment on the case, saying only it is “an ongoing investigation.”

Speaking to the Free Press at the time, Don Stevenson said his daughter was walking with friends when a man on a bike approached them and asked if they knew where he could buy some marijuana.

“They said, no — and then he started shooting,” said Stevenson, who died in 2017.

Samantha was shot in the stomach and had surgery to remove part of her bowel.

Pam Cameron, Samantha’s older sister, was at her West End home that night, when she received the shocking news.

“I started to panic, I started screaming, I wanted to go to the hospital as fast as I could,” Cameron said in a recent interview. “I got my friends to watch my daughters and I rushed to the hospital right away.”

While she would recover from her physical injuries, Samantha’s life was never the same again, Cameron said. “She was a totally different person (after) she got shot. We lost her that day — she didn’t die, but we lost the innocent little girl she was.”

Today, Samantha Stevenson, 23, is in prison, serving two years for robbery — a crime Cameron and court records suggest is directly tied to addictions, most recently methamphetamine.

The shooting “had a significant effect on the trajectory of her life,” Stevenson’s lawyer told a judge at her sentencing in June 2019.

Stevenson had a life “of some promise, then she was a victim of a crime,” her lawyer said. “And from there on she turn(ed) to substance use to self-medicate and follow(ed) a trajectory that has had her in and out of custody.”

Cameron said she turned her sister in, when she learned police were looking for her for a robbery.

“I just couldn’t stand seeing her the way she was anymore,” Cameron said. “It was a big decision for me, but I had to do it… I just wanted her off the streets, because I couldn’t stand how deteriorating her body was getting from the drugs.”

Being shot “really did a number on her,” she said. “We’ll never know if it didn’t happen if she’d be a different person… but I do know it had a negative impact on her life.”

Stevenson declined to talk to the Free Press.

A year after the attacks, city police confirmed the incidents were linked. The shootings on Dufferin and Boyd avenues were targeted attacks by one or more suspects tied to the North End “drug sub-culture,” but it didn’t mean Beardy or MacDonald were the intended targets, police said.

Beardy was dropping off food for a friend when he was shot, and had no direct connection to the address.

“He was at the (back) door and apparently got shot in the back,” said Tim Harris of Harris Foods, where Beardy worked as a meat cutter. “It was all just so random.”

Harris said he heard about the shooting the next morning at work, but only learned Beardy had been killed a day later.

“(It) hit pretty hard, hit everyone here actually, because he got along with everyone,” Harris said in a recent interview.

Meat cutting was just one of three jobs that kept Beardy busy supporting his family.

“He was a great worker, always worked hard,” Harris said. “He was super nice, funny, always had a good story.”

“He was at the (back) door and apparently got shot in the back. It was all just so random.” – Tim Harris of Harris Foods, where Thomas Beardy worked as a meat cutter

Cameron has her own ideas about the shootings, saying the circumstances suggest some kind of gang initiation.

“I think it was random, but I think the person that did it was being initiated into a gang,” Cameron said. “Just because of the three people who were shot, there was no connection (between any) of them.”

A suspect description released by police described a male between 5-8 and six-feet, with a slim or skinny build, wearing baggy dark clothing with red patterns and a hoodie. He may have worn a baseball cap and was seen riding a BMX or mountain-style bike.

“Someone’s gotta say something sooner or later,” Harris said. “It wasn’t that late in the evening; people were out and about. You would think someone would have seen something.”

In a community where many residents have become sadly accustomed to gang violence, the 2010 shooting spree is a harsh reminder of the dangers sometimes lurking outside their doors.

In the wake of the shootings, the Indian and Metis Friendship Centre organized a safe Halloween, bringing trick-or-treating indoors, a tradition that lasted several years. Media attention put a national spotlight on crime in the inner city.

However, time passes and memories fade.

“It may have scared (people) for a while, but then life went on,” Harris said.

dean.pritchard@freepress.mb.ca

Someone once said a journalist is just a reporter in a good suit. Dean Pritchard doesn’t own a good suit. But he knows a good lawsuit.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.