Inspiration from the Interlake William Prince's new album has 'Manitoba sound,' explores music of his roots

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 23/10/2020 (1873 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

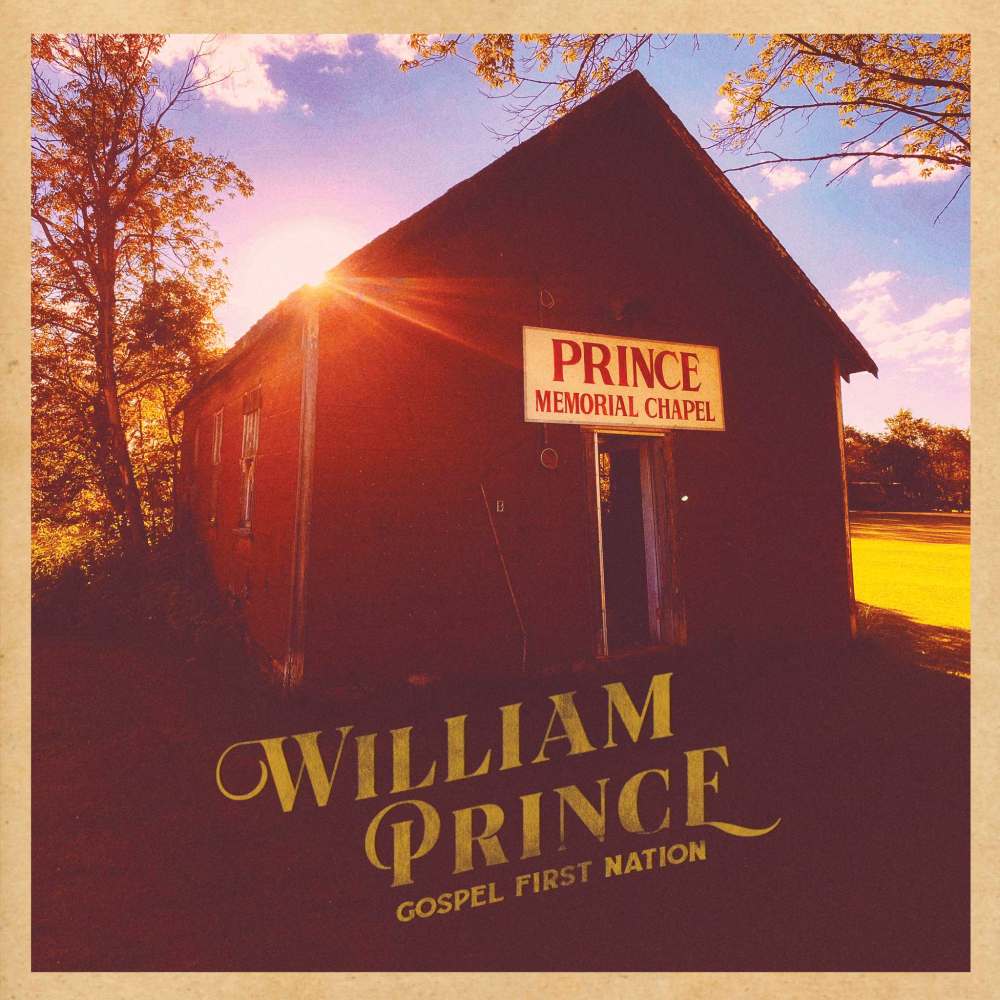

If William Prince were a movie franchise, Gospel First Nation would be his origin story.

The local singer-songwriter’s surprise new album, which comes out today, hearkens back to his youth growing up in Peguis First Nation and how he learned the craft of singing and writing songs from his father, Edward.

“It’s been cool to explore songs from when I was still really learning music, doing my best to keep up, to now when I’ve learned a little more and I can apply a refined take on these songs I grew up singing,” Prince says.

As the title says, it’s a gospel record — three new Prince songs that follow the theme are joined by six gospel covers as well as This One I Know, a song his father wrote during his career as a singer-songwriter and performer in northern Manitoba.

Edward Prince worked in the nickel mines in Lynn Lake, and later for the government, his son says, but in his free time he would travel to the many First Nations in Manitoba’s Interlake and sing in churches, community halls and bars and sell his records out of the trunk of his car.

He’d sing his songs, as well as country favourites by Johnny Cash, Charley Pride and Kris Kristofferson, at First Nations such as Fairford and Fisher River and as far north as Opaskwayak Cree Nation near The Pas and in Thompson.

“One of the favourites was always Little Saskatchewan First Nation, a few hours from Peguis. My dad formed friendships there; he would be a guest preacher, so to say,” William Prince remembers. “They would house us for a evening or a night, feed us and look after us and then we’d return the favour when a travelling minister would come through Peguis and need a place.

“We would offer our help anyway we could. It’s about the community, about people taking care of one another.”

It would be on these trips along the highways and gravel roads of northern Manitoba where a young Prince would pick up the basics of being a performer.

“That experience helped form exactly a good part of who I am today,” he says. “Learning how to make records and learning how to not make records. It’s invaluable, his contribution.”

When Jesus Needs an Angel is a song he wrote at age 14, a time when he’d accompany Edward at church services, wakes and funerals. It’s difficult to listen to the song without thinking back to past tragedies marked at memorial chapels or cemeteries.

“That song was in response to a community’s loss of a great presence in the church community, a beloved member of the Peguis First Nation who passed on,” Prince remembers. “My dad was going into the studio to record his third record at the time and I was trying to make his record a little bit different by providing original gospel music.

“That was one of the first instances that I can vividly remember where songs feel like gifts — they write themselves in that way…

“I guess I was trying to imagine if you’d lost your mother. You’re standing there at graveside and it’s the final moments before you let someone go forever. What’s appropriate to say, let alone sing?”

Christianity is a difficult topic for Canada’s Indigenous people, and Prince addresses this contentious issue in an artist’s statement that he released Monday along with the album’s title track.

He recognizes Christianity has been a tool used to colonize and assimilate Aboriginals in Canada. Faith groups were often at the heart of the country’s decades-long residential school system that abused children, separating them from their parents and their ancestral culture and languages.

Still, many Indigenous families like the Princes grew up enjoying gospel songs and admiring the country singers who performed them.

“It’s been beneficial to me, not to people in general,” Prince says. “Some traditional people, any talk of Christianity is triggering because of what it represents in the form of suffering we’ve been through.

“For me, I take the joy, the nostalgia and the memory of being in those moments with my family. My dad travelling around to different communities and setting up in different churches and having a great time working on my musicality, feeling the spirit of these songs, witnessing how these songs move people who come from somewhat bleak places.

“These are impoverished First Nation communities in Manitoba and these elders come together and celebrate the joy of being alive with a bit of message, testimony, fellowship and song. There’s a beautiful thing in that. There’s community to that.”

In the song Gospel First Nation, Prince calls out one of those communities, Fisher Bay, which is northeast of Peguis on the western shore of Lake Winnipeg. In doing so he sings about a common Christian theme: that Jesus Christ is everywhere.

“Jesus just might live down in Fisher Bay / Blending in among the boats and lines / When it comes the winter nobody sees the Saviour anyhow / He could just hide out.”

Prince recorded the album in August in Winnipeg with many of the same musicians who backed him on his first record, Earthly Days, including producer Scott Nolan.

“I don’t come from a church background so it was a unique thing for me,” Nolan says. “I knew really early that this was really special, and then he brought in a new song, Gospel First Nation, and I thought ‘Wow, this is perfect.’ ”

Several songs on the album are gospel classics — Prince says his father often sang Charley Pride’s All His Children, and the younger Prince includes his own version.

The songs celebrate Christ in a lower-key manner than traditional gospel recordings from Nashville.

“There’s a Manitoba sound to this,” Nolan says. “Our engineer joked that our choir didn’t sound Southern Baptist, it sounded more like North Kildonan.”

Prince, like all artists, has had more time on his hands in 2020, owing to the pandemic. He had to scrap shows in Europe and the United States in the spring that were to promote Reliever, his second album, which came out in February.

Instead of being on the road, he’s spending more time with his son and partner, and Gospel First Nation is another result.

“It all started with Mother’s Day. Peguis was on lockdown and I dedicated a few gospel songs to my mom on a livestream I was doing and the reaction was quite enlightening and empowering and lifted me up in the moment, kind of like an old church service would,” Prince says.

Nolan wasn’t surprised Prince made something positive out of a bad situation.

“This was going to be a big year for him, but rather than being disappointed he chose to put it forward. That’s a very William thing to do,” Nolan says.

Prince joins a 2020 trend of artists who have used the extra time to record albums looking back at music that had inspired them.

In September, Kentucky country artist Tyler Childers released Long Violent History, an ultra-traditional string-band record that sounds like it came from the 1800s. On Oct. 16, Sturgill Simpson, one of Americana’s most popular artists, surprised his fans with Cuttin’ Grass Vol. 1 (The Butcher Shoppe Sessions), which is his take on bluegrass standards.

Prince felt an urgency to release this record to let music fans learn about the land he grew up in and the music Indigenous people in the Interlake listen to.

“I’m glad this album isn’t happening 10 albums from now. I like that it’s now while people are listening to me,” he says.

“If it’s not me to capture this geographical sound, this First Nations’ take on gospel music, it could get lost, because all the elders I grew up with learning this music are gone.”

alan.small@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter:@AlanDSmall

Alan Small has been a journalist at the Free Press for more than 22 years in a variety of roles, the latest being a reporter in the Arts and Life section.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Friday, October 23, 2020 1:34 PM CDT: Fixes typo, changes lyric from can to could