Shingoose’s vision paved way for future artists

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 15/01/2021 (1789 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

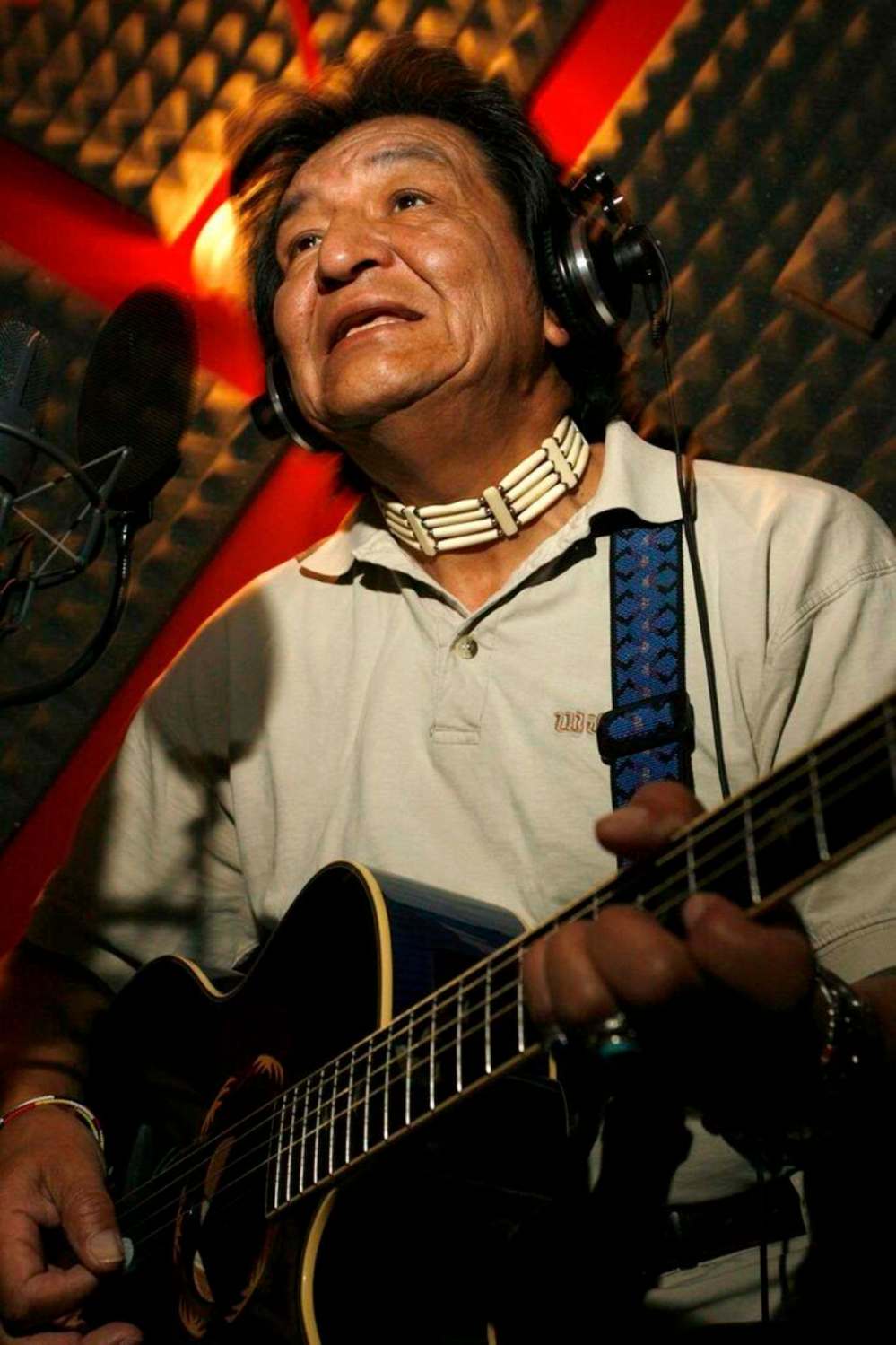

Dig into the life of Curtis Jonnie, the man behind Shingoose, the singer and songwriter, and you’ll discover the fascinating journey of a person who bristled at discrimination against Indigenous people and spent his life doing something about it.

In a way, Jonnie’s life, from his childhood at Roseau River Anishinaabe First Nation until his final days, symbolized what previous generations of Indigenous people in Canada faced and what they confront today.

His parents were residential-school survivors. What was supposed to be a temporary guardianship with an elderly lady in Steinbach, and later with the Knowles School for Boys in Winnipeg, became permanent, a process that later became known in Canada as the ‘60 Scoop, in which Indigenous children were raised in foster homes or adopted by settler families.

“I’m the second generation of a first generation that was never meant to survive. My parents went through the residential-school experience and suffered the residential-school syndrome. Yet here I am. I survived. But I never had the family experience,” Jonnie said in a 2016 Free Press profile looking back at his life and music career.

Jonnie died Tuesday at the Southeast Personal Care Home in Winnipeg after contracting COVID-19 at the age of 74. Despite warnings issued during the early days of the coronavirus pandemic in March 2020 that Indigenous people and seniors living in personal care homes could be particularly susceptible to the virus’s symptoms, he has become one of a growing number who have borne the brunt of Canada’s struggle with the deadly virus.

During his life, though, Jonnie was able to overcome many obstacles and forged a path for future generations of Aboriginal artists, both through his music and later with behind-the-scenes work with organizations such as the Manitoba Arts Council, the Juno Awards and Manitoba Music, advocating for Aboriginal performers.

“When it comes to being at the forefront of any cause, like Indigenous music, there’s always going to be barriers to be broken, and he did that,” says David McLeod, general manager of NCI and a vice-chairman of APTN. “He carried a torch for the generations to come.”

After leaving Manitoba, Jonnie learned to play music at the Boys Town orphanage in Omaha, Neb., and would make it his career. He made his way to New York and Washington, D.C., where he joined the band Puzzle; he played with famed American blues-rock guitarist Roy Buchanan in the late 1960s and early ‘70s. He would often pass on those experiences to younger artists, McLeod says.

“His background is incredible. Being part of the folk movement of the ‘60s, he was at the forefront of a scene, and that’s something a lot of people don’t realize, just how important he was,” McLeod says.

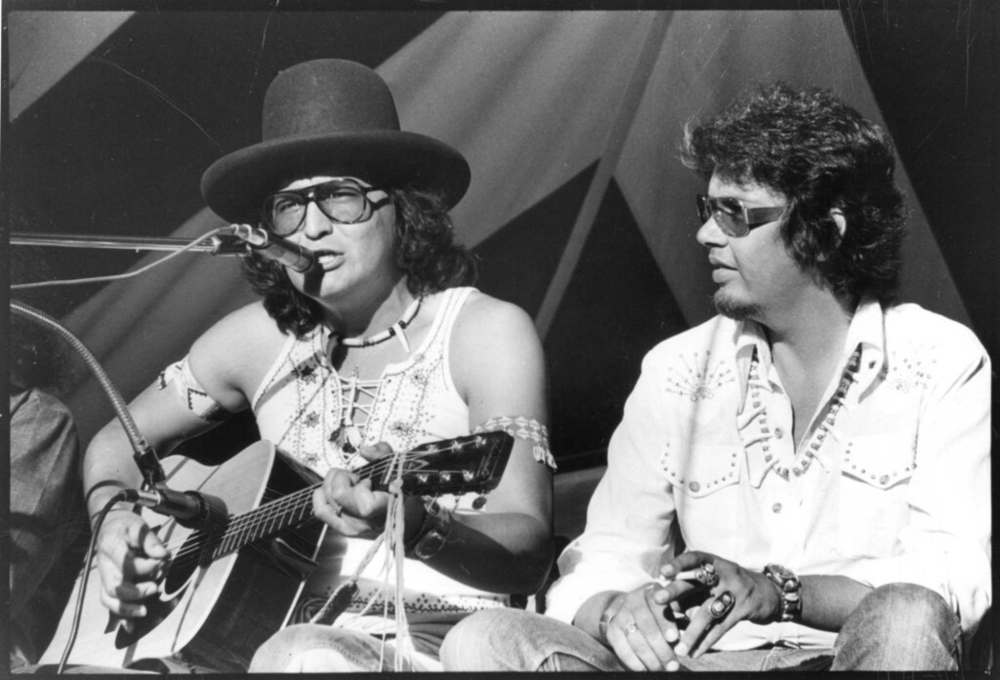

Jonnie moved to Toronto in 1973 where he performed solo in coffee houses under the name Shingoose, his grandfather’s name. It was there he met Duke Redbird, an Anishinaabe poet and spoken-word artist who was then vice-president of the Native Council of Canada, known as the Council of Aboriginal Peoples today.

It would be a friendship that would last for decades.

Neither were able to land recording deals, so they decided to create their own label, Native Country, and produced a four-song EP by that name in 1975. It was to be the first of many independent projects Shingoose and Redbird would be involved with in music, television and film.

“They all loved our music. I never talked to an agent or promoter who didn’t love the music,” Redbird says. “They always said, ‘We love the music but there’s no market. People don’t buy Indigenous music.’ It was way before its time.”

Perhaps the most well-known project Jonnie worked on — again under the Shingoose moniker — was Indian Time, a series of Gemini Award-winning variety specials he helped produce when he moved to Winnipeg in the 1980s. Redbird believes these shows were the beginnings that led to APTN’s existence as a television network in the 21st century.

Shingoose returned to prominence as a musician in 2016 when Kevin Howes, a DJ, journalist and producer, released Native North America Vol. 1, a compilation album of songs by Indigenous artists from the 1960s and ‘70s. A song from Native Country, Silver River, made it on the album, which was earned a Grammy Award nomination and was on the long list for the Polaris Prize.

The album’s success prompted a special Native North America workshop held at the 2016 Winnipeg Folk Festival. It allowed Shingoose a seventh and final appearance at the folk fest; he took the stage in a wheelchair, as a stroke in 2012 left him partially paralyzed.

Shingoose joined other artists whose songs appeared on the record, and the next generation of Indigenous singers and performers.

“Shingoose had a vision many years ago. He saw the possibility that could become a reality where Indigenous music is playing a major role in the music industry. That vision he had is becoming more and more at the forefront,” McLeod says.

William Prince, the Peguis First Nation singer-songwriter, was one of those on the folk fest stage that day, and his critical and commercial success in the years that followed owe something to Shingoose paving the way during his musical career.

“We have lost a trailblazer,” Prince wrote in an email to the Free Press. “He was essential in furthering Indigenous voices in folk music. One of the most memorable moments of my career thus far was sharing the stage with him at what would be his final Winnipeg folk fest performance.”

Shingoose still had dreams of performing, and Redbird says his friend was making progress in rehabilitation to regain more strength prior to contracting COVID-19.

“I talked to him just little over a month ago, and we were kind of scheming after the pandemic of getting back on the stage again,” Redbird says. “One more kick at the can, as we joked amongst ourselves.”

— with files from CP

alan.small@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter:@AlanDSmall

Alan Small has been a journalist at the Free Press for more than 22 years in a variety of roles, the latest being a reporter in the Arts and Life section.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.