Up in arms Manitoba is well behind Alberta and Quebec, where nearly all care-home residents have received a COVID shot; changing appointment protocols and delaying second doses could speed things up here

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 15/01/2021 (1884 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

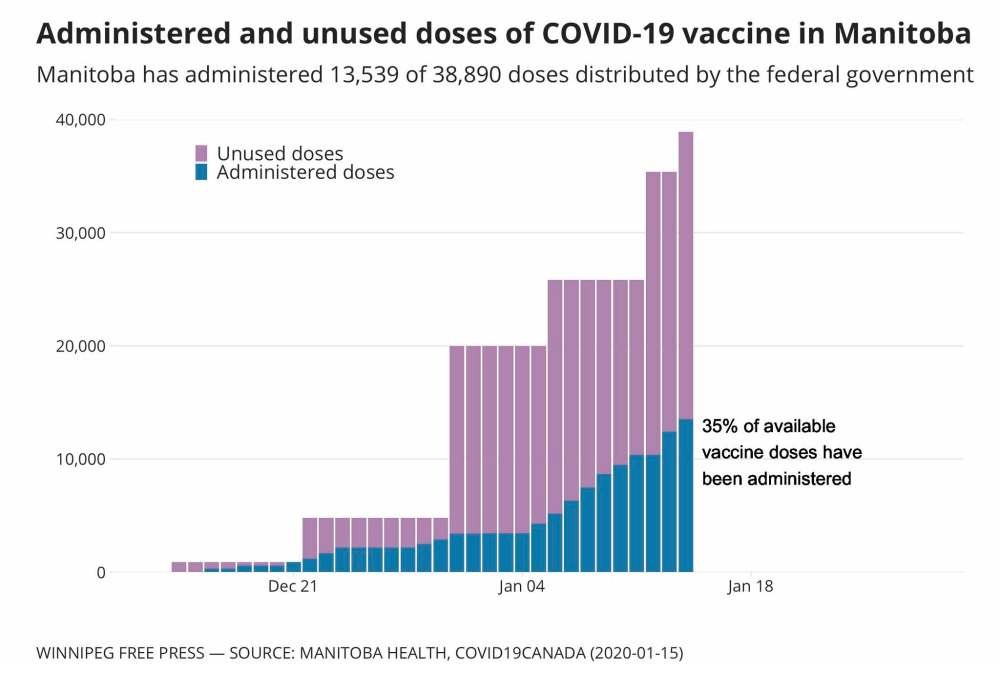

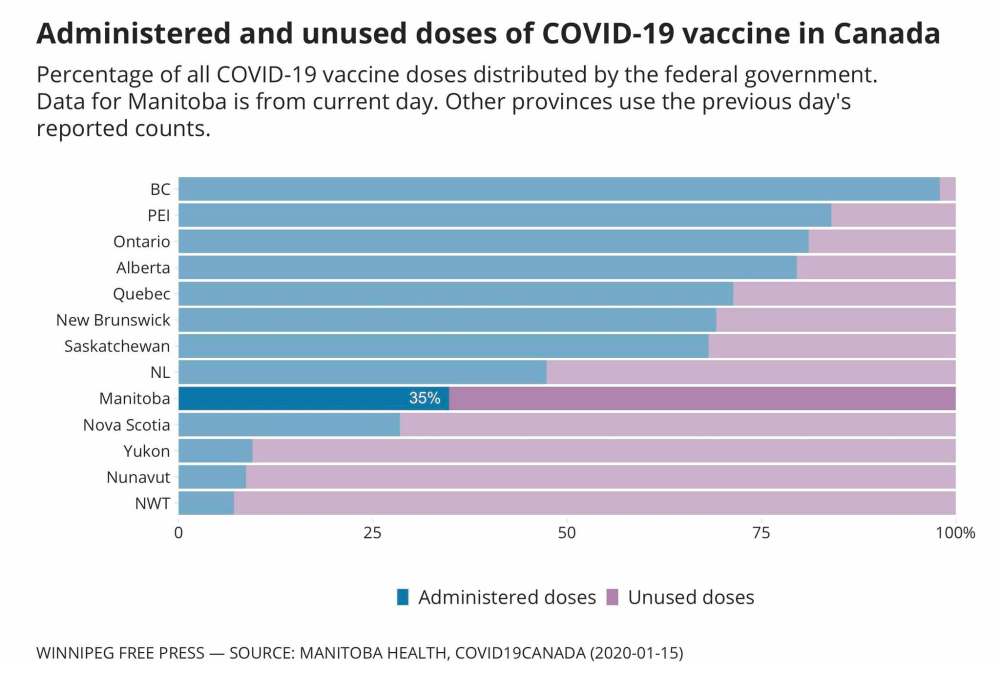

COVID-19 vaccines first arrived in Manitoba a month ago, and since then the province has consistently sat near the back of the pack in using the doses it’s received.

By this weekend, Alberta is expected to have given first doses to all long-term care and supported-living residents. Quebec is a few days behind.

It will take Manitoba about a month to reach that threshold.

Both those provinces show how Manitoba can ramp up, by automating booking systems and bending the timeline for second doses.

Alberta beefs up

As of Wednesday, Alberta had administered 97 per cent of the doses it has received, compared with roughly 40 per cent of Manitoba doses.

What’s helped is a centralized system, resulting from the controversial, gradual merger of all regional health authorities into one body, Alberta Health Services, in 2009.

Dr. Cheri Nijssen-Jordan, who co-leads Alberta’s vaccine task force, said the central agency created a transportation plan that ensured local areas got doses and vaccination supplies, and had started local priority lists.

Alberta started off among the slowest to get immunizations started, phoning workers who deal with COVID-19 patients in hospital wards, and calling in care-home staff to get immunized.

An online booking system launched Jan. 4, sending email invitations to health-care workers to schedule an appointment near their workplace. Alberta quickly outpaced other provinces.

“Once the decisions are made, it’s easier to scale up,” said Dr. Lynora Saxinger, an infectious-disease specialist at the University of Alberta.

“I actually think (this pace) will be quite sustainable,” she said.

AHS sent out invitations using staff lists maintained by hospitals and medical colleges.

“People don’t tend to keep up with their contact information very well, so it can be very difficult doing the directed-invitation method,” Nijssen-Jordan said.

Manitoba has an inverse process, in which officials ask workplaces to let staff know they’re eligible for a vaccine, giving them a number to call to register for an appointment. That meant hours-long wait times, which have now been reduced to 10 or 15 minutes; an online booking system is in the works.

“You can see arguments for either method,” Saxinger said, though she wonders if Manitoba’s phone-in method leaves room for interpretation on the other end of the line.

Like many other provinces, Alberta has published a schedule of its first phases of vaccine rollout, instead of Manitoba’s approach of expanding criteria in gradual drips, such as adding a profession or expanding age ranges by one year.

For example, Manitoba last week added “home-care workers employed by (a) family managed care client” to its eligibility list, meaning people in that field will have to call and convince health staff they fit that criteria.

“The toughest part will be in arranging the rollout through the priority groups in an efficient way. I think that’s going to be a bigger challenge than actually putting the needles into arms,” Saxinger said.

Nijssen-Jordan said the scarcity of doses imposes a huge burden of trying to prioritize the right people, instead of having enough doses to simply start going by birthdate. “Vaccine supply has been the real bottleneck,” she said.

Alberta pharmacists will soon be helping at vaccination clinics, an idea Manitoba is still only considering at its Winnipeg, Brandon and Thompson “super sites.”

But it’s worth noting that Manitoba is attracting notice from other provinces for its rapid immunization training, an eight-hour course provided by Red River College that teaches people how to administer injections and monitor people for adverse reactions.

Quebec pulls out the stops

The first person in Canada to get a vaccine was 89-year-old long-term care home resident Gisèle Lévesque. The Pfizer vaccine had arrived from Belgium to a rural Quebec airport the night before, was driven three hours away, prepared and loaded into syringes before noon.

COVID-19 has hit Quebec harder than any other province, and officials wasted no time in getting doses into the arms of the most vulnerable.

They stationed cold-storage freezers inside long-term care homes in as many regions of the province as they could — particularly those with large, ongoing outbreaks. Doses were stored in hospitals only in areas where care homes weren’t large enough for a freezer.

Unlike Quebec, most provinces chose to start with health-care workers. Manitoba began its personal care-home vaccination program four weeks after the first doses arrived, arguing it needed to prioritize hospital staff to ensure the health system didn’t collapse.

“In Quebec the immediate benefit is to save people from dying,” said Benoît Mâsse, a public-health professor at Université de Montréal.

Surgically targeting care homes has allowed public-health staff to go from room to room, sanitizing their gear between clients. They finish a care home in a day or two and then deploy to another one nearby.

That speed has meant that by next week, all personal care-home residents should have their first dose, something that won’t likely be achieved here for another month.

Only when this phase is done will Quebec open their large-scale walk-in sites similar to the big Winnipeg and Brandon clinics, where health-care workers have received their first vaccination shots.

Quebec has also boosted its vaccination rate by deciding — in a controversial move that conflicts with manufacturers’ guidelines — to delay booster-shot injections.

“We can get an immediate benefit from using all the doses, because we are in the middle of a very large outbreak,” Mâsse said.

That province says it will allow people to go as long as 90 days without their second dose instead of the recommended 21- to 28-day window.

Canada’s immunization council recommends stretching the period only to 42 days, because of potential risks.

Vaccines train the immune system to recognize viruses and form antibodies before the disease can take hold. Researchers don’t yet know whether that immunity wanes over time in people who haven’t received the booster.

Similarly, viruses that mutate can sometimes do so in people with weak immune systems, because the body is taking longer to defend itself, allowing the virus to adjust. It’s unclear how much risk there is in delaying the second dose beyond the recommended window.

The World Health Organization has said booster shots should only be delayed in times of vaccine scarcity when COVID-19 spread is high enough that widespread, partial immunity among the most vulnerable makes more sense than fully immunizing fewer people.

“There’s definitely a risk,” Mâsse said. “That doesn’t mean that we’re stuck with that strategy forever.”

Manitoba says it is monitoring outcomes from other provinces delaying doses before making any decision about doing so here.

On Friday, Ottawa announced that Pfizer had to alter its delivery schedule for Canada and some other countries because of manufacturing-plant upgrades, That means roughly half of the supply that was to arrive in February will be delivered, but the deficit will be made up with larger-than-planned deliveries in March.

Premier Brian Pallister said Manitoba was smart to stick with manufacturers’ recommendations, which eliminates the risk of patients waiting months for boosters.

A reconciliation lens

Part of why Manitoba’s rollout has lagged behind other provinces is a deliberate decision to put First Nations in the driver’s seat.

The 2009 H1N1 swine flu disproportionately killed Indigenous people, who were prioritized for vaccination in Manitoba. But a top-down approach fuelled conspiracy theories and a feeling that First Nations were used as guinea pigs.

Meanwhile, remote Indigenous communities don’t align with the national vaccine guidelines based around age, as they have significantly shorter life expectancy and higher instances of diseases that increase the risk of worse COVID-19 outcomes.

Pallister has thus left it up to First Nations leaders to decide which communities and groups get vaccines first, a process that meant Moderna doses sat in Winnipeg cold storage for 12 days.

“Some have said, ‘Well, you should have just sent the vaccines out right away.’ This wouldn’t have been respectful and it wouldn’t have been the right approach,” Pallister said.

His government wagers that will pay off in the long run, with more buy-in from First Nations and smoother communication as more doses reach Manitoba. (Métis leaders have complained they are not getting the same treatment.)

Compare that with Alberta, which doesn’t plan to reach a single First Nation until February.

Saskatchewan’s vaccine rollout has included some Indigenous communities, but only as part of a generic rollout to the North that First Nations leaders say isn’t meeting their needs.

Patchy data

Comparing the rapidly evolving rollout of vaccines in Canada is possible thanks to a group of volunteer data crunchers.

“It’s important so we can evaluate how the rollout is going in each province,” said Jean-Paul Soucy, a public-health PhD student at the University of Toronto.

Soucy is part of the COVID-19 Canada Open Data Working Group, which assembles the patchwork of data provinces record and release through different time frames and definitions, and tries to make sense of it all.

The group’s dashboard, showing how many doses are sitting in freezer, has fuelled political and media pressure on governments to get moving.

The federal government says it plans to eventually publish data on how provinces are administering vaccines, and Soucy hopes that will come soon.

“It’s a positive number to report; it’s kind of a ray of hope,” he said.

“But it’s also showing that public health, and the government, is fulfilling the bargain that was made, in terms of: we had to sacrifice Thanksgiving and Christmas, but things will be different (in 2021).”

Saxinger said that, in general, transparency can help avoid what will inevitably be a confusing few months.

“I think there’s going to be a bit of foot on gas-brakes-gas-brakes for a while, as we get the supply chain running and the capacity running and then the system to notify people when it’s their turn,” she said.

“I’m pretty confident the drama will be over pretty quickly.”

At that point, Saxinger said provincial governments will have to make it clear when their citizens get vaccinated, and how long public-health rules remain in place.

“Our media is transnational, and it creates more confusion, because people are not sure what rules they’re hearing about apply where they are, and they compare different rules from different places.”

dylan.robertson@freepress.mb.ca