Laughter, music, love — all on Indian Time

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 15/01/2021 (1790 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

It’s the winter of 1988, and I’m not happy when my parents tell me we are going to a concert called “Indian Time.”

I was 12, and not exactly proud of who I was. Since birth, I had been fed a steady diet of negative images of “Indians” in media — from savages in movies, criminals on the news, and poor, drunk, and broken people in books.

My father had just been appointed Manitoba’s first Indigenous judge, and I had successful relatives around me, but these images were dwarfed by the outside world.

That cold winter night, we entered Winnipeg’s Walker Theatre (now Burton Cummings Theatre) and the first thing I saw were the television cameras. The lights. And more Indigenous people than I’d ever seen outside of a pow wow.

After we found our seats, a tall man with a mullet and long straight black hair walked to a microphone, wearing a black leather jacket with long white tassels.

“Greetings, everyone,” he said, “I’m Shingoose.”

The man stopped and stood, surveying the audience. After what seemed like an eternity, he broke into a song called Indian Time.

I don’t remember much else, but I do recall: “Indian Time has often been misunderstood / Something gets bad, something is good / It’s kinda like the story of the turtle and the hare / It isn’t if you win or lose, it’s how you make it there.”

This was Curtis (Shingoose) Jonnie’s life message.

“He believed our people could live and be healed through art,” daughter Nahanni Shingoose-Cagalj says on the phone from her home near Toronto. “And, to the end, he celebrated 500 years of resistance and life through his music.”

Born Oct. 26, 1946, in Winnipeg, Jonnie died Jan. 12 at age 74 at a local care home, from complications due to COVID-19.

He leaves behind one of the most important musical legacies in Indigenous music history, including groundbreaking albums, sharing the stage with the biggest names in music, and legacies as a TV host, personality, and producer.

What I remember Shingoose best for, though, is showing me how beautiful Indigenous music, comedy, and culture is, during a time when it was virtually impossible to find in media.

That 1988 show — which appeared on TV stations across the United States and Canada throughout 1989 — was the first of three Indian Time variety specials. All were co-produced with Jonnie’s long-time collaborator (and former Free Press columnist) Don Marks.

The night I attended featured Shingoose, alongside musicians Buffy Sainte-Marie, Tom Jackson, Laura Vinson, Cree hoop dancer Billy Brittain, and (my favourite part) Oneida comedian Charlie Hill.

“I am still mad that my dad didn’t bring me that night,” Shingoose-Cagalj says with a laugh. “I missed out on one of the greatest collections of Native performers around.”

Joining them on stage was a non-Indian but one of the most recognizable faces in North America at the time: Shingoose’s lifelong friend Max Gail, who had starred as “Wojo” on the hit TV sitcom Barney Miller. (He won an Daytime Emmy in 2019 for his work on General Hospital.)

In an interview from his home in Los Angeles, the American actor talked in great detail about their friendship, travelling and living together in the 1980s, and his involvement in Indian Time.

“Goose was more than a friend,” Gail says. “Through him I got to meet people who would influence me across my career, and I’ll never forget my sketches with Charlie Hill.”

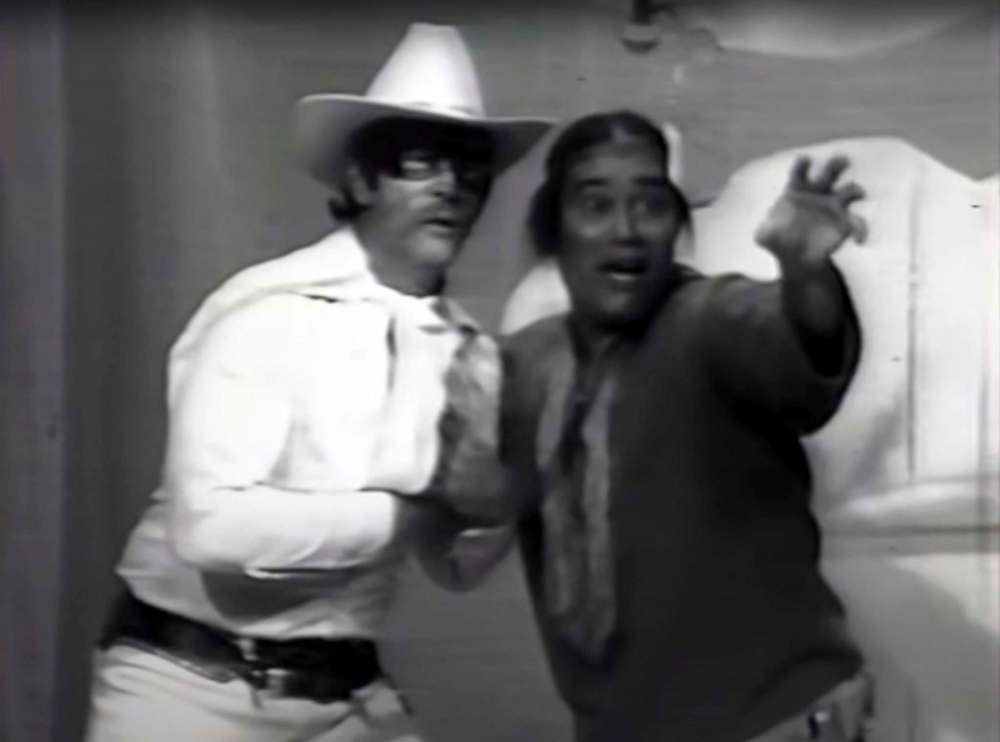

That first Indian Time featured two hilarious, political sketches most 1980s TV shows would not touch: one where the Lone Ranger (Gail) and Tonto (Hill) meet in Heaven to argue about was the “true hero;” another where a Hollywood producer (Gail) offers $10,000 to an Indian actor (Hill) to act out a bunch of stereotypes.

“Goose wanted to show people how funny Native culture is,” Gail says. “He really had a creative mind.”

Due to Shingoose’s influence, Gail would record thousands of hours of footage of Indigenous activist events and interview leaders, eventually becoming an advocate for Native American rights in Hollywood and political circles.

Their friendship was reciprocal.

“Through people like Gail, people were exposed to my father’s music and Indigenous culture, too,” Shingoose-Cagalj says. “They helped each other during a remarkable time.”

During their final conversation last year, Shingoose told Gail his dream was to reproduce Indian Time in 2021.

“I told him I’d be there,” Gail says.

This week, Shingoose-Cagalj started an online $100,000 fundraising campaign to make this happen.

Shingoose was right: “Indian Time” is how you make it here. Now it’s time for all of us to keep it going from the laughter, music, and love he gave us.

niigaan.sinclair@freepress.mb.ca

Niigaan Sinclair is Anishinaabe and is a columnist at the Winnipeg Free Press.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.